Zhīlā Musāʿid: Poetry at the Crossroads of Myth and Modernity

Figure 1: Zhīlā Musāʿid in her early forties, in Mīrzā Āqā ʿAskarī, “Rābitah-am bā jahān az tarīq-i kalimāt Ast” [My relationship with the world is through words], Muhājir 8, no. 70 (Ābān 1370/ November 1991): 23–29.

The Birth or Revelation of a Poet

Zhīlā Musāʿid (Jila Mossaed) (born 1327/1948) is an Iranian poet and fiction writer, and is the only naturalized Swede in The Swedish Academy (prize awarder for the Nobel prize in Literature), chair 15. She has published numerous collections of poetry in both Persian and Swedish. She hails from Tehran, where she was raised in a family known for intellectual and artistic pursuits. Her father, ʿAlā al-Dīn musāʿid, was a judge and poet who followed the Saʿdī style in his ghazals.1Author’s interview with Zhīlā Musāʿid, May 19, 2024; Zhīlā Musāʿid, Surkhʹjāmahʾī ki manam [The one clad in crimson, I am] (Stockholm: Arzān, 2001), 1.(see Figure 2)

Figure 2: ʿAlā al-Dīn musāʿid, “Ashk” [Tear], Pārs 34, no. 3920 (Shahrīvar 20, 1354/September 11, 1975): 5. (Courtesy of Tavakoli Archive)

In 1985, Zhīlā Musāʿid moved from the vibrant cultural landscape of her homeland of Iran to the foreign shores of Sweden. This cultural shift, from one rich tapestry of traditions to another, has undoubtedly shaped her poetry, infusing it with a unique blend of Iranian and Swedish influences. Today, she is celebrated as a renowned poet in her adopted country.2Since 1996, Musāʿid has written in Swedish. In 1997, she became the first non-Swedish poet to receive the Gustav Fröding scholarship, and in 1999, she was awarded the AFB literary prize in Sweden. See Musāʿid, Surkhʹjāmahʾī kih manam, 1. However, her journey as a writer and poet began much earlier, with her first short story published in the Firdawsī Journal under the pen name of M. Murvārīd, when she was vacillating between writing poems and fiction.3Author’s interview with Zhīlā Musāʿid, May 19, 2024. (see Figure 3)

Figure 3: M. Murvārīd [Zhīlā Musāʿid], “Man va fikr va pardahʹhā” [Me, thought, and curtains], Firdawsī 13 (Farvardīn 1347/April 1968): 19.

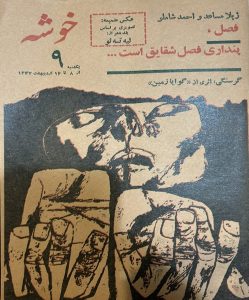

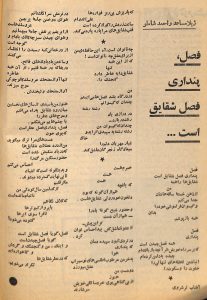

She composed her first poem when she was in the fifth grade of high school, a testament to her early passion and talent.4Author’s interview with Zhīlā Musāʿid, May 19, 2024. Her exceptional gift was evident even in her teenage years and was recognized by a prominent Iranian poet, Ahmad Shāmlū. Her early works were published in Firdawsī and Khūshah journals, in which Shāmlū first acknowledged and admired her poetry. In a note titled “Khvāharān-i shiʿr” (Sisters of poetry), Shāmlū praised Zhīlā and her sister Mahvash’s work, noting that despite their youth and limited education, their poetry was of a high standard. (see Figure 4)

Figure 4: Ahmad Shāmlū, “Khvāharān-i shiʿr” [Sisters of poetry], Khūshah 7 (Farvardīn 25, 1347/April 14, 1968): 9. (Courtesy of Tavakoli Archive)

Shāmlu was so impressed by Zhīlā Musāʿid’s poetry that he decided to collaborate with her on a poem, “Fasl pindār fasl –i shaqāyiq ast” (The season sounds to be a season of poppies), which holds a significant place in the history of Iranian literature and serves as a testament to the depth and breadth of Musāʿid’s poetic influence. As Kāmyār ʿĀbidī, an Iranian literary critic, mentions in one of his articles, the history of the first co-authored poem in Iran dates back to a story by Dawlatshāh Samarqandī that appeared in Tazkirat al-shuʿarāʾ, about a poem believed to have been composed by the famous classical poets Firdawsī and ʿUnsūrī Balkhī, among others. Many prominent contemporary Iranian poets such as Hūshang Ibtihāj, Nādir Nādirpūr, Furūgh Farrukhzād, and Yad Allāh Rawyāyī, also published co-authored poems.5Kāmyār ʿĀbidī, “Az shiʿr-i kuhan-i Fārsī tā shiʿr-i mudirn-i āmrīkāyī” (From ancient Persian poetry to modern American poetry), Jahān-i Kitāb 28, no. 401 (Day 1, 1402/December 22, 2023): 41. One of the most intriguing examples of these is the poem Hūshang Ibtihāj and Nādir Nādirpūr co-authored, which first appeared in the Rawshanfikr journal. (see Figure 5)

Figure 5: Hūshang Ibtihāj (Sāyih) and Nādir Nādirpūr, Rawshanfikr 161 (Shahrīvar 15, 1335/September 6, 1956): 16. (Courtesy of Tavakoli Archive)

Though many collaborative poems were literary pastimes, the collaboration of Musāʿid and Shāmlū stands out. Its highly complex form and structure elevate it beyond mere amusement, categorizing it as one of the leading poems of its era (see Figure 6 and 7).

Figure 6: Ahmad Shāmlū and Zhīlā Musāʿid, “Fasl pindārī fasl-i shaqāyiq ast” [The season sounds to be a season of poppies], The Cover page of Khūshah 9 (Urdībihisht 8, 1347/April 28, 1968). (Courtesy of Tavakoli Archive)

Figure 7: Ahhmad Shāmlū and Zhīlā Musāʿid, “Fasl pindārī fasl-i shaqāyiq ast” [The season sounds to be a season of poppies], Khūshah 9 (Urdībihisht 08, 1347/April 28, 1968): 9. (Courtesy of Tavakoli Archive)

However, studying archives of the time leads to the question of whether Zhīlā Musāʿid and Shāmlū indeed co-wrote it. Firdawsī Journal published this poem a year after Khūshah Journal, under the name of Zhīlā Musāʿid’s sister Mahvash Musāʿid. Additionally, based on an interview with Zhīlā Musāʿid, this poem belongs to Mahvash Musāʿid, which Shāmlū edited without her permission and published under his name and, mistakenly, that of Zhīlā Musāʿid.6Author’s interview with Zhīlā Musāʿid, May 19, 2024. (see Figure 7)

Figure 8: Mahvash Musāʿid, “Fasl pindārī fasl-i shaqāyiq ast” [The season sounds to be a season of poppies], Firdawsī 904 (Farvardīn 12, 1348/April 1, 1969): 30.

Musāʿid is a well-established poet in Sweden,7See Jenny Fossum Grøn, Nordic Voices: Literature from the Nordic Countries (Oslo: ABM-utvikling, 2005), 38; Ann-Sofie Lönngren, Heidi Grönstrand, Dag Heede, and Anne Heith, Rethinking National Literatures and the Literary Canon in Scandinavia (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015), 64. but she remains almost unknown among Iranian audiences. Iranian critics have been silent about her work, and there are no academic studies on her Persian poetry.

From Godless Mythologies to Atheist Poetry

This study focuses on Musāʿid’s Persian poetry and showcases how her passion for criticizing religion and religious ideology led her to the realm of mythology.8The works discussed in this study are listed below: Musāʿid, Māh va ān gāv-i azalī (Stockholm: Ārash, 1993). Zhīlā Musāʿid, Surkhʹjāmahʾī ki manam (Stockholm: Arzān, 2001). Zhīlā Musāʿid, Iqlīm-i hashtum [The eighth clime] (Stockholm: Arzān, 2004). Zhīlā Musāʿid, Rūd-i talkh: Zindah′am nigāhʹdār [Bitter river: Keep me alive] (Stockholm: Bārān, 2008). Zhīlā Musāʻid, Pinhānʹkunandahgān-i ātas [The concealer of fire] (Stockholm: Dūstī, 2011). Zhīlā Musāʿid, Dar īn khānah-yi bī dar khvābam namīʹbarad [I cannot sleep in this doorless house] (Stockholm: Arzān, 2018). The following note can be considered Musāʿid’s literary manifesto:

Exile leads you back to your origin, to a political, religious, and historical self. It forces you to investigate your role in the world.

You must learn your country and culture’s roots, history and language to discover a strong identity. This process is best done in exile.

This is why I began researching Mithraism and Zarathustra and [reading] the [Qur’an]. I also read about gnosis prior to Islam and the ancient humanist self-knowledge that elevates humanity’s potential for goodness and unites it with the concept of God. I visited the ocean from which Rumi, Hafiz, and many of the great ones have drunk and swum in. I camp by this ocean so that I can learn more.

I found out that my country is my language and that the cultural mummies that have besieged my memory make me feel at home amongst the people of my homeland, but in no way free.

I realized that the myths that slumber within me and are anchored in my country of origin help me become conscious about my mythological self and find my place in the world’s cultural landscape.

It is common to come across traces of Greek mythology in Western literature. In contrast, ancient Persian culture was prohibited and hidden by holders of religious power. It was not displayed and could not be discussed openly.

The war against our old philosophy and literature continues under the present regime in Iran. The joy which lay as the foundation of life was transformed into a crying culture of grief.

At the time when great thinkers, poets, and philosophers such as Rūmī and Hāfiz were forced to write their works in the languages of those in power, embellishing them with religious words, people did not have the internet nor great access to books, which we have today.

These poets were geniuses. They were wise enough to weave their work into mystery and write in a way that would come to protect their books [They were wise enough to write their poetry in such a mysterious way to let them keep writing and to protect the manuscripts.]

Those in power had no well-founded reason to arrest them and[or] burn their books, even though their works express strong critiques of and resistance towards religious hypocrisy and the Sharia law.

Writers in Iran are in the same situation today as they were then. Books are rigidly censored and turned into paper dough [i.e. sent to the pulp mill] by the regime’s machinery. All criticism of religion and politics is banned.9Zhīlā Musāʿid, “Language is a soft and delicate piece of cloth in which every mother wraps her child,” Visa Vis (21 February 2017). https://bit.ly/3QqY4Qe

This lengthy yet crucial quotation shows how Musāʿid deliberately incorporated mythological themes and maintained a clear distinction between religion and mythology. In her perspective, religion and mythology exist in separate realms of thought. Where religion is perceived as against humanity and wisdom, mythology is considered ancient knowledge and wisdom that poets should acknowledge. Her definition of religion is similar to that of the philosophers who belittle mythology as a “dangerous infection that spreads over the whole body of human civilization.”10Ernst Cassirer, The Myth of the State (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1946), 19. Hence, ironically, one could argue that mythology is as valuable to her as reason and rational thinking are to philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment. However, there are no clear boundaries between the ambiguous realms of religion, mythology, and poetry, to the extent that “in poetry and religion mythical thinking continues to the present day.”11Frederick Clarke Prescott, Poetry & myth (New York: Macmillan, 1927), 62.

In the introduction to one of her poetry books, Māh va ān gāv-i azalī (The moon and that primordial bull), Musāʿid discusses the mythological background of the title and a nostalgic feeling toward the past stands out throughout the book.12The bull referred to in the title is the first creation of the Zoroastrian supreme God Ahūrah Mazdā, among animals. See Musāʻid, Māh va ān gāv-i azalī, 1. The first poem in this collection, “Davāzdah hizār sāl” (Twelve thousand years) refers to the Twelve Thousand Years of Zoroastrianism:13Philip G. Kreyenbroek, “Cosmogony and Cosmology I. In Zoroastrianism/Mazdaism,” in Encyclopedia Iranica Online, accessed July 6, 2024, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/cosmogony-i

Find twelve thousand lost bulls,

And the bull that sought refuge in the

moon.

…..

And man, with a horrifying howl,

lamented:

Find the bulls

to take me to the cave, which is still

glowing

With the sparkles of the pure semen

of the Eternal Bull.

I will be waiting there

till the moon comes to my bed.

Maybe again

the droopy and dried womb of the cosmos

becomes full of seeds and roots of love.14Musāʻid, Māh va ān gāv-i azalī, 11–12.

دوازده هزار گاو گمشده را بیابید

و آن گاو

که در ماه پناه جست

….

انسان با فریادی دلخراش، شکوه کرد

گاوان را بیابید

تا مرا به غاری ببرند

که هنوز

از تلالو نطفهی پاک گاو ازلی روشن است

من در غار منتظر می مانم

تا ماه به بالینم درآید

شاید دوباره

زهدان خشک و پژمردهی جهان

از ریشه و دانههای مهر پر شود

The poet longs to return to a time before civilization and religion when the sacred bull, considered God’s first creation, had not been slaughtered yet. It is better to state that, based on Iranian mythologies:

The original bull myth (as it can be reconstructed from Zoroastrian sources) appears to have been that after they had created the world, the gods sacrificed the first man, the uniquely created bull (gav–aēvō.dāta-), and the original plant, so that from them came all races of men and all kinds of creature and plants. In Zoroastrianism, it is Ahriman who kills rather than sacrifices, but the yazatas, having taken up the bull’s seed to be purified in the moon, then still caused all other creatures to spring from it, so that in Zoroastrianism also the uniquely created bull is the mythical first animal.15Mary Boyce, “Cattle,” in Encyclopedia Iranica Online, accessed July 6, 2024, https://iranicaonline.org/articles/cattle#pt2

Finally, the poet seeks solace in the land of mythology, represented in the text by words like “cave” and “womb.” Love is something forgotten in this poem, which belongs to the past.

Another poem from this collection, titled “Jahān-i man pillah nadārad” (My world does not have stairs), compares the pure and soft nature of imagination to a cruel, ugly, and masculine view of reality:

I am a wanderer of the plains,

A passenger of the earth’s surface

And I cannot believe

Green stairs leading to the wreckage of

human imagination,

And the false climax of masculine flesh,

Begging for eternal orgasm!

My world does not have stairs,

And is empty of tempting deceptions,

For finding an absent God

And fear, the pillar of delusional books,

Never could conquer my soul!16Musāʿid, Māh va ān gāv-i azalī, 17–18.

مسافر دشتم

مسافر سطح زمین

و پلههای سبز را

که به ویرانههای تخیل انسان می رسد

و قلههای کاذب عروج مردان تن را

که به دنبال انزال ابدی می گردند

باور نمی کنم

جهان من پله ندارد

و از اوهام فریبکارانه

برای جستن خدایی غایب

خالیست

و ترس

که شیرازه کتابهای دورغین است

هرگز به فتح روحم قادر نشد

This poem expresses the opinion that God does not exist and that fear is the only tool religion uses to control people. Another poem gives the sense of being trapped in historical passivity but finding solace in her dreams, filled with images of extinct instincts.17Musāʿid, Māh va ān gāv-i azalī, 22–24.

Atheism is one of the central themes of Musāʿid’s works. Her aversion to religion influenced her rhetoric to the point that even her friend and role model, Zhālah Isfahānī, says of her, “Zhīlā is a restless, unsatisfied, rebellious and highly-strung poet who wholeheartedly fights against social disparity, oppression, and cruelty,” but “pessimism and death overshadow part of her poetry.”18Zhālah Isfahānī, “Ātash-i āshkār” [Manifest fire], Par 6, no. 71 (Āzar 1370/November 1991), 32–33. This anxious and angry immigrant woman poet is highly critical of religion, but ironically idolizes the warmth and love of the East against the coldness of the West’s reason and rationality:

This is the second time

that I have taken the flower of fire

and run

From my homeland,

From my bed,

From my cradle and my grave.

This time, I have brought the flower to

the land of ice!19Musāʿid, Māh va ān gāv-i azalī, 25.

این بار دوم است

که گل آتش را

برداشته میگریزم

از سرزمینم

از بستر خوابم

از گهواره و گورم

این بار

گل را

به سرزمین یخ آوردهام

She migrated to the icy land of Sweden and gifted the “flower of fire,” symbolizing the purity of Persian poetry, to her new land, but she is unsure if her “fire” can survive in a “cold memory” of her new host.20Musāʿid, Māh va ān gāv-i azalī, 26. Although one could argue that Musāʿid ultimately finds comfort in Western culture, her poem “Gharb” (West) provides a critique of the West in a manner that brings to mind the well-known Iranian intellectual movement known as Gharbʹzadigī [Westoxification], which is attributed to Ahmad Fardīd and popularized by Jalāl Āl Ahmad:21For additional information on Ahmad Fardīd and his intellectual journey, see Ali Mirsepassi, Transnationalism in Iranian Political Thought: The Life and Times of Ahmad Fardid (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

I encountered the West

when I was eight

The West did not have a family

The West was a celibate

It was our neighbour

And it built roads for us

…

But one day,

the young girls on the street

Witnessed the West’s fingers fumbling

under the skirt of the youngest among them22Musāʿid, Māh va ān gāv-i azalī, 90–91.

من غرب را

وقتی که هشت ساله بودم

ملاقات کردم

غرب زن و بچه نداشت

غرب تنها بود

و همسایهی ما بود

غرب برای همه ما جاده می ساخت

….

اما یک روز

دختران کوچک کوچه

دیدند که

انگشتان غرب

به زیر دامن کوچکترینشان لغزید

Like many Iranian intellectuals critical of immoral Westernization, Musāʿid regards the West as a technological advancement that scapegoats morality.23For additional information, see Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi, “Ahmad Kasravi’s Critiques of Europism and Orientalism,” in Ethos: A Critique of Eurocentric Modernity, by Ahmad Kasravi, trans. Hamid Rezaei Yazdi (London: I.B. Tauris, 2023), 1–15.

As a modern poet, Musāʿid nostalgically approaches the past in her poem “Āhū” (Deer), similarly to many Iranian intellectuals and modernists before her. She compares the horror of rootless modernity to the purity of nature in the lines “The gazelle comes back, looks at the cement height, and dies.”24Musāʿid, Surkhʹjāmah′ī kih manam, 20.

In “Man, Insān” (I, human), her pessimism about humanity, which can be seen as a complete contrast to Shāmlū’s optimism towards humans,25One can compare this poem to Shāmlū’s “Dar Āstānah.” See Ahmad Shāmlū, Dar Āstānah (Tehran: Nigāh, 1375/1996). is evident in her summary of human history:

The world has been sacrificed,

The lives of animals and vegetation,

Upon the altar of my greed,

…

If any god were to be created,

Would it be more vicious than me?

From the delicate body of basil

To the hard core of coconut,

They are all servants to my lust.26Musāʿid, Māh va ān gāv-i azalī, 31.

جهان قربانی من است

جان حیوان

درخت و گیاه

در بارگاه ولع من

گرفته شد

….

آیا هیچ خدایی

موحش تر از من

آفریده شد؟

از تنِ تُرد ِ ریحان

تا دل ِ سخت نارگیل

در خدمت شهوت من

In “Safar” [Travel], Musāʿid adeptly balances form and theme, echoing the renowned Iranian poet Sīmīn Bihbihānī’s “Naghmah-i Rūspī” [The ballad of the courtesan].27See Sīmīn Bihbihānī, Majmūʿah ashʿār [Collection of poems], (7th repr. ed., Tehran: Nigāh, 1394 /2015), 1: 21–23. While depicting the harshness and cruelty of the modern masculine world, she deliberately strips away metaphors, confronting the issue directly:

I saw my sisters

Who were selling my dead body

To be satiated

And not to freeze

And you [men] have always been the

buyers

Buyers of the bodies of your

daughters, your sisters, and your

mother’s body.28Musāʿid, Māh va ān gāv-i azalī, 46–47.

خواهرانم را دیدم

که تن مردهی مرا می فروختند

تا سیر باشند

تا یخ نزنند

و شما همیشه خریدار بودهاید

شما خریدار جسم دختران

خواهران

و مادران خویش بودهاید

Musāʿid critiques religion in simple poetic language in “Iʿtirāf” (Confession). She refers to herself as an infidel, stating that human creation occurred before the appearance of God.29Musāʿid, Rūd-i talkh: zindah′am nigāhʹdār, 65–66. However, this boldness is not a permanent fixture in her poetry, as she artfully intertwines her work with symbols. She uses red astringent pomegranates to represent the blood of young girls and the bitterness of their sorrow, thereby marrying womanhood with nature.30Musāʿid, Māh va ān gāv-i azalī, 56–57. Also, a careful examination of all her works could suggest that even her seemingly overt atheism cannot be strictly classified as modern atheism or secularism, because some aspects of mysticism or sophism are also present in her atheistic poems. For example, one of her minimalistic poems is reminiscent of Farīd al-Dīn ʻAttār’s Mantiq al-tayr [The conference of the birds]:31See Farīd al-Dīn ʿAttār, Mantiq al-tayr [The conference of the birds], ed. Muhammad Rizā Shafīʿī Kadkanī (4th repr. ed., Tehran: Sukhan, 1384/2005). “From the worshipping of stone, I transitioned to the worshiping of the mirror/ I saw myself and created God.”32Musāʿid, Māh va ān gāv-i azalī, 111.

از پرستش سنگ

به پرستش آئینه رسیدم

خود را دیدم

و خدا را آفریدم

Another anti-religious poem shows how this theme should be interpreted as anti-ideological rather than strictly anti-religious:

Death makes them naked,

The soil covers them.

Come with me, Mom,

Together with mothers who are

carrying shrouds.

They are completely naked

under the veil of the soil.

[Look at] the purity of humans, torn by

The mullahs’ dagger.33Musāʿid, Rūd-i talkh: Zindah′am nigāhʹdār, 17.

مرگ عریان می کند

خاک می پوشاند

مادرم

با من بیا

با مادران کفن بر دوش

لختند

لخت لخت

زیر چادر خاک

عصمت پاره شدهی انسان

با چاقوی ملایان

One could argue that Musāʿid’s poetry, which criticizes religion, is not entirely similar to the anti-religious poetry of Iranian nationalist poets during the Constitutional Revolution era, such as Mīrzādah-yi ʿIshqī. However, her poetic critique of religion can be seen as an extension of that theme following the period of the Iranian Islamic regime. Her poetry is much more sophisticated than the poetry of that era; although she does not use rhyme and meter, she creates a harmonious dichotomy by intertwining the paradoxical themes of religion and mythology. Ironically, in her poetry, naked women are portrayed as pure, while the Mullahs, who are supposed to represent morality, are actually against the purity and chastity of human beings. Another of her poems, “Khatābah” [Oration], can be seen as a daring criticism of clerics and mullahs. In “Tawhīd” (Monotheism), she describes God as “a spider trapped in his webs,”34Musāʿid, Rūd-i talkh: zindah′am nigāhʹdār, 24. and in “Ghūl”, she calls ‘religion’ and ‘tradition’ monstrous.35Musāʿid, Surkhʹjāmah′ī kih manam, 56.

In most of her poetry, Musāʿid laments the loss of beauty in the past and criticizes the ugliness of the present. However, she also refuses to turn to religion, viewing it as a form of barbarism.36See Musāʿid, Dar īn khānah-yi bī dar khvābam nimīʹbarad, 64. In Persian classical poetry, different elements of nature, such as water or soil, represent more significant values beyond each element.37See Muslih Ibn ꜥAbd Allāh Saꜥdī Shīrāzī, Kulliāt-i Saꜥdī [Complete works of Saꜥdī], ed. Muhamad ꜥAlī Furūghī (12th repr. ed., Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1381/2002), 4. In Musāʿid’s works, by contrast, each part of nature is independent and can even be tempting.38Musāʿid, Pinhānʹkunandagān-i ātash, 66. Her anger towards Iran’s ideological regime sometimes causes her poetic language to transform into political slogans.39Musāʿid, Pinhānʹkunandagān-i, 10. However, her high-concept themes, such as nature, religion, and mythology, often lead her poetry towards surreal and complex imagery that is uncommon in Persian poetry, such as “The bloody umbilical cord of the earth / is caught in the sacred mouth of a cloud.”40Musāʿid, Iqlīm-i hashtum, 33.

بند ناف خون آلوده زمین

در دهان مقدس ابری گیر کرده است