Opening the Drawn Curtain: Decoding the Gendered Personhood of the ‘Woman Poet’ in Persian Poetry

Of all the many ways in which literature can be delineated and categorized, distinctions along gender lines are perhaps the most complex. Debate around this label, and its implied hierarchy of writerly worth, remains divisive and unresolved in both literary and academic discourse. What do we mean by ‘a woman poet’? How does this definition influence our understanding and interpretation of their work?At its simplest, a woman poet is a woman who breaks through patriarchal structures to write, be published and read. This in itself can be read in two ways: as both an assertion of female empowerment and an acceptance of gendered hierarchy. If, as the Persian poet Simin Behbahani describes it, there is a “curtain (pardeh)… drawn between men and women writers,”1Farzaneh Milani, Words and Veils: The Emerging Voices of the Iranian Women Writers (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1992), 11 then it is essential to examine the role this “curtain” plays in valuing and then canonizing women poets and their work.

This paper will explore the impact of gendered nomenclature specifically within the Persian literary canon. How has the idea of the ‘woman poet’ evolved in a country where female identity, both on and off the page, is a complex and shifting concept in itself? What insights can be gained by comparing the Persian literary landscape with other cultures and points in time? As Andrew Ashfield concludes in his study of the canonization of English Romantic women poets, the characterization of women’s literature has been either “perversely masculine, ‘unsex’d’, or sweetly feminine [to ensure] that it can never be canonical and survive as a persistent object of attention.”2Andrew Ashfield, “Introduction,” Romantic Women Poets 1770–1838, edited by Andrew Ashfield (Manchester, 1995), xii Similarly, we shall see the ways in which Persian women poets have been systemically downplayed, dismissed or misrepresented, often as a consequence of what I call ‘anecdotal gendering’ by historiographers.

While the term ‘woman poet’ is generally assumed to be a product of female identity politics of the twentieth century, literary historians and scholars have argued that its emergence precedes the modern period.3For British female poetry canon formation, see Terry, Richard. “Making the Female Canon,” ed. Terry, Richard, Poetry and the Making of the English Literary Past: 1660-1781 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 252-285. For a similar discussion in the Persianate context, see Farzaneh, Milani. “Words and Veils: The Emerging Voices of the Iranian Women Writers (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1992). In the case of Persian literary history, the origins of spatial segregation in the literary miliue can be traced back to the inception of Persian poetry itself.

The systemic relegation of women to the margins of Persian literary history is no surprise, given that the earliest Persian poetic canons were borne out of, or shaped around, the highly masculine order of the court. For centuries, the royal court only appointed male poets. The male presence spilled out beyond the court into everyday life in which women were invisible under patriarchal politico-economic structures and social roles. As a result, the visibility of male poets, both on and off the page, led to their work being anthologized in biographical accounts, or tazkirahs, which remain the foundation for scholarship around the Persian literary tradition to this day.But does the systematic invisibility of most women poets from the tazkirahs necessarily mean there were no women poets? Dominic Brookshaw, in his study of Qajar princess-poets, suggests that there may well have been an elite network among courtly women poets circulating and reciting their poems; it is only that they were destroyed, rather than preserved:

The loss of divans [poetry collections] of women poets was most likely more common than the loss of those of male poets. This gender discrepancy must be attributed (in part at least) to residual anxieties about women’s writing in general, and, more specifically, about the preservation of their compositions in a written form (and the increased potential for public dissemination of a woman’s poems that this written form of the text facilitated).4D. P. Brookshaw, “Women in Praise of Women: Female Poets and Female Patrons in Qajar Iran,” Iranian Studies, vol. 46, no. 1 (2013), 18-19.

In other words, a fear of becoming visible caused women to be written out of literary history. The consideration of preservation and posterity is therefore inextricably linked with gender as both a social and literary construct—an important factor in how, and why, traditional canons were established. In most cases women were reduced to archetypal personae by a patriarchal readership. The life and character traits of the poet overtook any attention paid to her work, with innocence, femininity, and devotion pitted against carnality and untrustworthy charm. Chastity (‘iffat) was fetishized while sexual transgression was punished. In the valuing of woman’s poetry, the male gaze blocked any potential for meritocratic review; the same male gaze, however, allowed their poetry to be published and preserved.

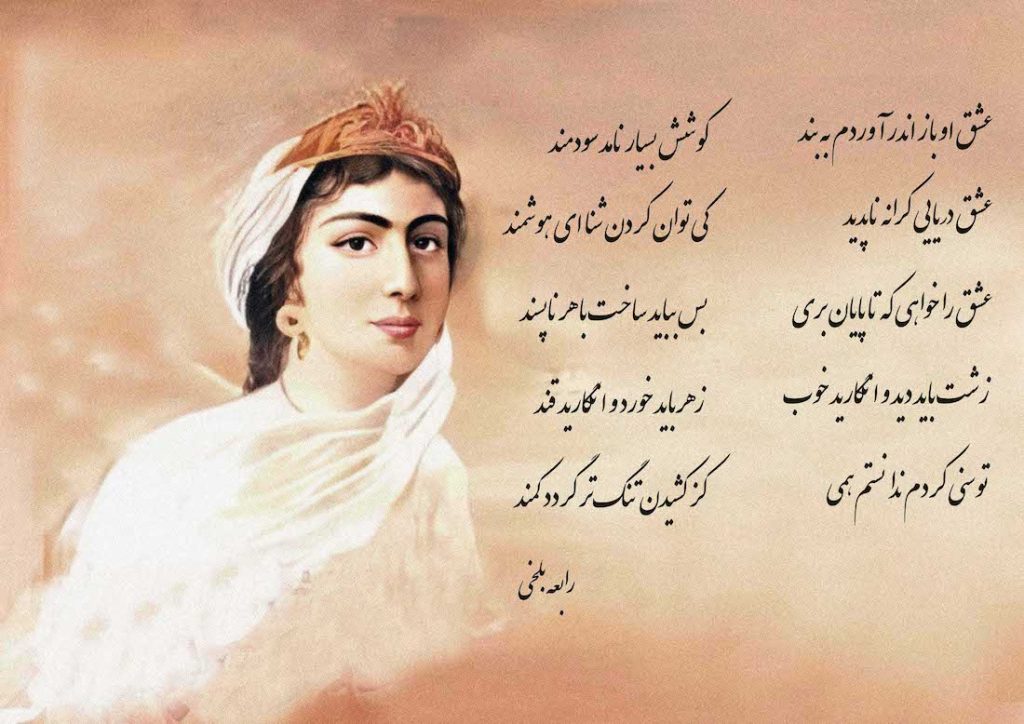

Tenth century poet Rabe‘eh Balkhi (also known as Rabe‘eh Bint-i Ka‘b Quzdari), is a compelling example of this. Celebrated as the first Persian woman poet, her widespread recognition was perpetuated, not by the worth of her poetry, but by her tragic life in which her love for a courtly slave named Baktash led to her murder at the hands of her brother, King Hares.

Similarly, the name of medieval poet Mahsati has been preserved in history in a deeply gendered fashion. When referenced as a poet, a legend was often built around her physical and/or moral qualities in male-authored tazkirahs, such as the eighteenth-century Riāz al-Shu‘arā by Vāleh, bolding her as a poet, a beautiful prostitute, and the beloved of Sultan Sanjar.5See Sunil Sharma, “From ʿĀesha to Nur Jahān,” 155. Although Vāleh seems to have read poems by women poets rather closely and carefully, his commentaries are not free of gender-based biases. For example, when praising Bibi Māh Āfāq for her poetic talent, Vāleh measures her qualities as if she is a man, “she lived like a man” (mardāeh ma‘āsh mikad).6Sharma, “From ʿĀesha to Nur Jahān,” 156. For him the poetic quality of a woman poet at a young or old age always seems to be a paucity.

Without being reductively fetishized, however, women poets could lose the opportunity for historical presence and significance altogether. The fourteenth-century princess-poet Jahān Malik Khatun, a contemporary of well-known poets Hafez Shirazi and Ubayd Zakani, is one such example. Although she compiled her own divan, it took 600 years for her work to be finally recognized by literary scholars.

Towards the end of the Timurid era in the sixteenth century this systemic negligence began to slowly change. A male poet called Fakhri Haravi compiled a women-only tazkirah published under the title ‘Jewels of Wonder’ (Javahir al-‘ajāyib), also known as ‘The Biographies of Women’ (Tazkirat al-nisā’). As the literary historian Maria Szuppe7Maria Szuppe, “The Female Intellectual Milieu in Timurid and Post-Timurid Herāt: Faxri Heravi’s Biography of Poetesses, “Javāher Al-‘Ajāyeb,” Oriente Moderno (1996), vol. 15, no. 76, p. 119-137. and others have argued, this improvement is particularly evident during the rule of the last significant Timurid ruler of Herat, Sultan-Husan Bayqara (d. 912/1506), offering a turning point for the conceptualization of the woman poet. Sunil Sharma, however, asserts that most of the women poets in the ‘Jewels of Wonder’ anthology had no substantial oeuvre “and their names are merely records of the small but constant participation of women in the production of [female] literature.”8Sunil Sharma, “From ʿĀesha to Nur Jahān: The Shaping of a Classical Persian Poetic Canon of Women,” Journal of Persiante Studies 2 (2009), 152. Nevertheless, this groundbreaking tazkirah offers, as Szuppe says, “a rare glimpse of female education and status among the urban administrative, religious and political elites, even if some were only recently settled, in a milieu which was always considered the most socially conservative.”9Maria Szuppe, “The Female Intellectual Milieu in Timurid Period,” 123. In short, while Heravi’s attempt to commit female poetry to the page demonstrates progress towards an idea of ‘the Persian poetess,’ it fails to create a distinct poetic genre produced by women poets.

Twentieth century women poets too, have struggled against the enduring legacy of this double-edged sword, which has been arguably worsened by the denigration of women in modern day Iran. In a literary establishment still rooted in the patriarchal structures of the past, the challenge of separating their womanhood from their poethood remains.

The most popular woman poet of today’s Persian-speaking domain, Forugh Farrokhzad, spoke passionately about how misogynist narratives tainted the understanding and reception of her work.10To read more on Farrokhzad’s poetry, see Farzaneh Milani, “Love and Sexuality in the Poetry of Forugh Farrokhzad: A Reconsideration,” Iranian Studies, 1982, vol. 15, no. 1/4 (1982), 117-128. In a well-known interview with Iraj Gergin, Farrokhzad was asked to elaborate on the “femininity” (zanānah budan) of her poetic output. She replied:

If my poetry as you mention has a feminine quality, it naturally has to do with me being a woman. Fortunately, I am a woman. But when it comes to the evaluation of artistic values, I believe that to speak of sex as a measuring criterion is irrelevant and inappropriate.11Farzaneh Milani, Words and Veils: The Emerging Voices of the Iranian Women Writers (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1992), 11.

Farrokhzad pushed for a move away from gendered thinking, declaring: “The male/female binary is not worthy of any attention.” She explained the “feminine” aura of her work was not intentional, but rather an “unconscious” (nākhudāgāh) unfolding of her existence. As she concluded: “The most important thing is to be Human (insān),” a gender-nuanced Arabic loanword.12Milani, Words and Veils, 11.

Farrokhzad’s contemporary, the poet Simin Behbahani, voiced similar criticisms of gendered categorization. In an interview with Dunyā-yi Sukhan magazine, she said:

I suffer from this curtain (pardah) that is drawn between men and women writers. If a poet is truly a poet why should the issue of sex turn into privilege? The arena of poetry is no wrestling ring in which sex and weight are criteria for categorization.13Milani, Words and Veils, 11.

By dissociating gendered categorizations from “the arena of poetry” (‘arsah-yi shi‘r), Behbahani invites her readers and critics to move away from what feminist theorist Judith Butler describes as “regulatory fictions that consolidate and naturalize the convergent power regimes of masculine and heterosexist oppression.”14Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990), p.44 As Farzaneh Milani notes, rejecting gendered classification is underpinned by the “implied concern that placing women in a gender-marked category automatically downgrades their work to a subsection created especially for them. Isolating women from the mainstream of Persian literature, understood to belong to men, is feared to be damaging, at best condescending, to women.”15Farzaneh Milani, Veils and Words, 11-12.

Farrokhzad’s death in 1967 coincided with the global rise of feminist scholarship in which many of her and Behbahani’s assertions would find theoretical justification. French feminist philosopher and linguist Luce Irigaray writes in her book, This Sex Which is Not One (1977), that women are women already, and for this reason, any definition or categorization of femininity imposed upon women by patriarchy is to be confronted:

How can I say it? That we are women from the start. That we don’t have to be turned into women by them, labeled by them, made holy and profaned by them. That that has already happened, without their efforts. And that their history, their stories, constitute the locus of our displacement … how can we speak so as to escape from their compartments, their schemes, their distinctions and oppositions: virginal/deflowered, pure/impure, innocent/experienced … How can we shake off the chain of these terms, free ourselves from their categories, rid ourselves from their names? Disengage ourselves, alive, from their concepts?16Luce Irigaray, This Sex Which is Not One (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1977), 211.

In her groundbreaking book, Gender Trouble (1990), Judith Butler takes a similar stance by resisting the arbitrary binary of femininity versus masculinity, employing instead the term “gender” in which there are various gendered identities that are fluid, inclusive, and open to change, while the terms “feminine” and “masculine” are products of a phallocentric approach. Gender in its Butlerian sense moves beyond biology to define it as a social construct, a fiction, that is mutable and unfixed.17Judith Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” Feminist Critical Theory and Theatre, ed. Sue-Ellen Case (Baltimore: John Hopkins, UP, 1990), 273. In other words, gendered classification is not neutral, free of judgement; it is merely a way of ordering books on shelves. It is a pernicious statement of hierarchy, the result of a societal parti pris that consistently otherizes women.

As we saw in the words of the poets themselves, as well as those of scholars in the field, gendered labelling has served to dilute or undermine women’s poetic output. In the case of medieval women poets, their lexicon is quickly dismissed as imitative and cliched by male critics, who saw their work as weak derivatives of male poetic output, thus excluding them from the right to preservation. In other words, and for the most part, women poets of the pre-modern era have been castigated for internalizing the masculine poetic lexicon; forgetting, of course, that language itself is a phallocentric domain and to write is an almost Faustian pact with the Symbolic Order in Lacanian terms. To this end even non-subversive verse written by women poets is to be considered as a rupture. Again, the doomed efforts of the princess-poet Jahan Malik Khatun to self-canonize by compiling her own divan serves as a good example here.

Anecdotal Gendering and the Making of the First Persian Women Poet

A quick glance at historical accounts about the first Persian-speaking woman poet reveals mechanisms of anecdotal gendering and ways in which her persona has been appropriated by male authors across different periods. Even at a basic level, her name Rabe‘eh Quzdari has been appropriated by different male historiographers to impose their own projections of womanhood upon her, simultaneously referred to as “The daughter of Ka‘b” (bint-i Ka‘b), “The beauty of Arabs” (Zayn al-Arab),18Farid al-Din Attar Neishabouri, Elāhināmeh, ed. Mohammadreza Shafi‘i Kadkani (Tehran: Sokhan, 2008), 371. and ‘The Mother of Persian Poetry’. All these titles allude to a specific mode of anecdotal gendering: the emphasis on her royal lineage in the title “bint-i Ka‘b,” the reference to her physical beauty in the title “Zayn al-Arab,” and the appraisal of her literary status by linking it to the gendered reproductive term “mother”. In each term, the poet’s gender roles have been already defined and prescribed by the masculine structures of power that presumed heterosexual and heteronormative parameters in the formation of such categories. Through these titles we can see how womanhood has been imagined, metaphorized, heteronormalized, and fetishized.

It is interesting, then, that we know next to nothing about Rabe‘eh’s life. Very little of her poetry– around fifty-five lines – survives and historical accounts about her life are far from accurate. In short, she is a historical enigma, whose real and embodied personhood has been overtaken by myth, speculation, and appropriation by centuries of male authors and poets. From the narratives that have survived of her life story, we know that she was a victim of honor killing in the hands of her king brother, Hares, who ordered her murder after discovering her love for a courtly slave named Baktash. Her gendered persona has been constantly fabricated by male authors who have imagined her either as a boy-chaser or a Sufi. Sunil Sharma has briefly pointed to the mystical and non-mystical duality that has been attributed to her character by different male authors.19Sunil Sharma, “From ʿĀesha to Nur Jahān,” 151. Safoura Nourbakhsh too, has examined her status in the Sufi discourse of love established by Attar.20Safoura Nourbakhsh, “The Costly Transgression: Woman as Lover in Sufi Discourse,” Sufi Journal of Mystical Philosophy and Practice, no. 98 (Winter Issue, 2020), 37-41. I will build upon these works to elaborate on the anecdotal gendering of her poetic persona and ways in which it has overshadowed her technical and aesthetic contributions to the Persian poetic tradition.

‘Awfi is the first author to reference her as a poet within a non-mystical framework in a tazkirah, titled Lubābul-albāb:

Although she was a woman, Rabe‘eh the daughter of Ka‘b excelled all men of her time in her command of knowledge and intellect. She was fluent in both Persian and Arabic and rhymed proficiently in both languages. She was extremely skillful and intelligent. She constantly fell in love and toyed with charming youth.21Noor Al-din Muhammad ‘Awfi Bukhari, Lubāb Al-bāb (Persian Edition), ed. Edward Browne (London-Leyden, 1930), entry 51, page 61.

‘Awfi portrays Rabe‘eh as accomplished, intelligent and high-achieving in spite of her womanhood. The opening conjunction “although” establishes the masculine mode of intelligibility as a default mode of being. It alludes to an exclusionary gendered classification of women as a species who must be evaluated by rules of exception. In other words, her success in the male-dominated world is swiftly undercut by the reminder that she is a mere woman after all—a coquettish, flirtatious being who happens to be intelligent. The sudden intrusion of the term “shāhid bāzi” (boy-chasing) without any explanation of the term as a way of commenting on a woman’s sex life, is an example of anecdotal gendering that he does not apply to his biographies of male poets.

Although ‘Awfi does mention Rebe‘eh’s masterful linguistic knowledge and rhyming abilities, he does not recognize her as one of the first—if not the first—practitioner of macaronic verse as a distinct poetic genre in the Persian tradition. It is important to note that Rabe‘eh’s presence was foundational to the formation of literary norms that established macaronic verse as a poetic genre in the Persian tradition. As Dick Davis notes in the introduction of his anthology, The Mirror of My Heart (2019), which covers a thousand years of Persian poetry by women, “as far as we know, [Rabe‘eh] is the first Persian poet to write macaronic verse—that is, verse that is written in two languages, usually in alternating lines; in Rabe‘eh’s case the alternating lines are in Arabic and Persian.”22Dick Davis, Mirror of My Heart: A Thousand Years of Persian Poetry by Women (Washington D.C, Mage Publishers, 2019), xxii. In the Persianate domain, Davis adds that “Rabe‘eh was not merely a woman who happened to write verse at a moment when Persian poetry was being reborn, but that her role in this revival was crucial and perhaps decisive. Her circumstances and achievement indicate that she was someone whose example made possible the revival of Persian poetry—at least in terms of its major non-Persian model.”23Davis, Mirror of My Heart, xxiii-xxiv.

Besides Abdulrahman Awfi’s brief paragraph, we find the second most comprehensive anecdotal account about Rabe‘eh’s in Attar’s Ilāhināmah (Book of God), which gave rise to her mystical persona. Most probably written shortly after Awfi’s Lubāb ul-Albāb, Ilāhināmah is a key text in Persian Sufi literature comprising mystical tales told by a king father in response to the queries of his six sons. Rabe‘eh’s tale has been framed as an example of mystical love in the twenty-first discourse of the Ilāhināmah, where the father king is teaching his sixth son about love:

There is no love other than the profane love (ʻishq-i majāzī). If you seek perfection in love, you must be perpetually in three conditions: weeping, burning, bleeding. If you cross these three seas, your beloved will accept you and let you in. And if not, thorny strains will be placed on your path.24Farid al-Din Attar Neishabouri, Elāhināmeh, ed. Mohammadreza Shafi‘i Kadkani (Tehran: Sokhan, 2008), 371.

Throughout the anecdote, Attar takes great pains to construct Rabe‘eh as a lover of the Divine and thus cleanse her of profane love. Nourbakhsh has noted that “Attar’s aim is to show that, like Layla and Majnun story, Rabe‘eh’s love for Baktash as an example of profane love (ʻishq-i majāzī) is a vehicle for spiritual love (‘ishq-i haqīqī).”25Nourbakhsh, “The Costly Transgression,” 41. In Attar’s Ilāhināmah, Rabe‘eh’s multilayered character is ultimately overtaken by her metaphorical love for the Divine. Throughout the tale, we observe at least three figures: Rabe‘eh, the poet-lover who constantly pushes against, and competes with, Rabe‘eh, the sister/daughter/princess on the one hand, and Rabe‘eh, the mystic-lover the Divine, on the other.

Attar does not refer to Rabe‘eh by her name, but by her two titles, “Daughter of Ka‘b” and “Beauty of Arabs.” In his characterization of Rab‘eh as a young, beautiful, gifted empress-poet, Attar heavily relies on conventional tropes and figurative attributes that were commonly employed in romance epics of Nezami, especially his Khusrau and Shirin which is said to have influenced Attar in crafting his Ilāhināmah:

In that court, he [Ka‘b] also had a daughter whom he loved so dearly. The name of that young beautiful girl was the Zain al-Arab [Beauty of Arabs]. She was an attractive, lovely girl. She was the queen of the realm of charming faces. She possessed all the worldly beauty. In her presence, intellect turned into madness. She was the legendary beauty in the world.26Attar, Ilāhināmah, 371-372.

In fifteen couplets, Attar documents his depiction of Rabe‘eh’s physical beauty in a similar hyperbolic tone and anecdotal style that we find in Nezami’s Khusrau and Shirin or Fakhr al-Din As‘ad Gorgani’s romance epic, Vis and Ramin using such familiar metaphors as the moon, heaven, and the pearl to build a perfect woman with astonishing physical beauty that entails legendary proportions. Later, and similar to Awfi, Attar praises Rabe‘eh’s remarkable poetic skills:

In poetic talent no one outshined her. She immediately improvised and rhymed whatever she heard from those around her. She rhymed masterfully as if boring pearls together. Her lips tasted like poetry and she excelled in poetic delicacy and eloquence.27Attar, Ilāhināmah, 372.

Here, Attar builds upon Awfi’s brief account about Rabe‘eh’s distinct abilities in rhyming by adding one more quality to her poetic persona: skillful improvisation, which, as we know, was one of the essential qualifications of the court poets. The famous anecdote in Nezami ‘Arouzi’s Chāhārmaqālah (Four Discourses) about Roudaki’s improvisation before his patron Amir Nasr Samani to convince him to return to his capital, Bukhara, or the well-known story of Ferdowsi’s improvisation before his fellow court poets, Onsori, Asjadi, and Farrokhi are two canonical accounts.28Julie Scott Meisami, Medieval Persian Court Poetry (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1987), Ch.1. In one way, Attar’s admiration for Rabe‘eh’s improvisation skills puts her on an equal ranking with that of her male counterparts. But historically speaking, none of the male authors who wrote about Rabe‘eh canonized her as the initiator of such crucial poetic skills and genres.

In another passage of his anecdote, Attar refers to Rudaki’s meeting with Rabe‘eh and once again reiterates her excellence in improvisation:

Rudaki was passing through one day and he saw that cheerful girl seated on the path. If he rhymed a verse precious as golden water, she would rhyme a better poem. He improvised a handful of poems and to all she responded right away. Rudaki was astonished again and amazed by the well-disposed poetic gift of his tender, loving companion.29Attar, Ilāhināmah, 384.

Whether historically accurate or not, the passage suggests a context in which, despite the highly segregated setting, court women poets may have occasionally had brief personal encounters and literary exchanges with their male counterparts. But as Attar makes clear, the presence of women poets was strictly limited when it came to preforming poetry before the patron. We learn about the circulation of women poets’ works though male-only courtly recitations in the following lines of the anecdote:

When the king asked Rudaki to recite a poem, the master stood up and began to rhyme. He recited poems of Ka‘b’s daughter from memory and they deeply enthused the gathering. ‘Who wrote this poem? It looks like someone has adorned [us] with pearls,’ said the king.30Attar, Ilāhināmah, 384.

Here we see a courtly tradition being shaped through a woman’s voice in the absence of her body. Unlike Awfi who fetishizes Rabe‘eh’s womanhood by calling her a “boy-chaser,” Attar makes every effort to sanctify her and construct a spiritual figure whose love transcends physical limits of the human body. In this binary, we observe the duality of Rabe’eh’s poetic qualities versus her appropriated sexual acts and desire, both of which are also closely tied to her courtly class and lineage controlled by her male custodians (father and brother). This becomes clear in multiple episodes of the anecdote where Attar highlights the masculine gaze over Rabe‘eh’s life and her response to Baktash’s love. One such episode is when Rabe‘eh’s father asks his son and successor, Hares, to take charge of his sister’s life after his death:

Her father adored her and protected her. Upon his looming death, he asked his son to be in charge of her life.31Attar, Ilāhināmah, 372.

In the aftermath of her father’s death, and in a sexually segregated courtly environment controlled by the male gaze, Rabe‘eh meets her brother’s slave named Baktash. After a frequent exchange of letters, the two finally happen to encounter one another in a garden’s corridor. In Attar’s version, when Baktash desperately tries to touch her body, Rabe‘eh refuses to allow him and renounces her love for him:

One day [Rabe‘h] passed through a corridor. Baktash suddenly saw and recognized her after a long time fantasizing her lovely face. He grabbed her skirt and she was infuriated. She moved away and said: “you are ill-mannered. How dare you touch me? You are a fox behaving like a lion? No one can touch my shit, who are you to grab my skirt?32Attar, Ilāhināmah, 379.

What stand out more than anything in these lines are the social class tensions between an empress and a slave—the fox versus lion binary which further plays into the patronizing tone of Rabe‘eh in demeaning Baktash’s social status. Whether out of fear or from a position of power, Rabe‘eh’s words do not convey any mystical message about the nature of her love. However, Attar elaborates on these lines and reframes them to justify the renunciation of her profane love for Baktash in favor of her transcendental love for the Divine:

I have entangled [with love] in my heart and it has been epitomized in you. Even hundred slaves could not bear this pain. I have shown you my love and that is all. Is it not enough for you to be a pathway [the love of Divine]? You have not set an appropriate foundation for this [love] and have unleashed your sexual desire instead.33Attar, Ilāhināmah, 379.

Attar uses the word “kār” (task, job) to mean “‘ishq” (love) employs a well-known Persian expression, “kar uftādan bā…” (to be entangled with…) which has been commonly used in the mystical literature to mean “falling in love.” In the Sufi doctrine, love is an incident that captivates the soul and the heart of the lover. To be entangled with love is a full-time occupation which its strict regulations and norms. Decoding the Sufi lexicon of the poem helps us trace the mystification of Rabe‘eh’s puzzling behavior in her encounter with Baktash. Whether or not Attar’s account of their encounter is accurate or mythologized, it is clear that Attar attempts to negate any form of physical intimacy between Rabe‘eh and Baktash based on gender rules and sextual prohibitions and norms of the time. After Rabe‘eh disappears from the scene, Attar turns his readers’ attention to a major Sufi figure, Abu Sa‘id Abulkhair (Bu Sa‘id of Mahna) as a reliable source to legitimize his narrative:

I heard from Bu Sa‘id of Mahna who said when I arrived there and asked about Ka‘b’s daughter, she had become a devout mystic. He said it was revealed to me that her poems could not be about profane love. Those poems had nothing to do with humans. She was in love with the Divine.34Attar, Ilāhināmah, 379.

Attar’s narrative later on became a source of inspiration for other Sufi poets who tried to canonize Rabe‘eh as a mytical figure. The fifteenth century poet, Abdul-Rahman Jami officially named Rabe‘eh in a list of Sufi women in his Nafahat al-uns:

Sheikh Abu Sa‘id Abul Khair (God bless his soul) has said: “The daughter of Ka‘b was in love with that servant. But all old (male) Sufi masters agreed that what she said (recited) could not be addressed to a human being. [Her heart] was engaged elsewhere [with God]. One day that servant ran into her and reached for her sleeve [to touch her]. She screamed at the servant and said: “Isn’t it enough for you that I am in love with God, did I say anything to you that you have become so voracious?” Sheikh Sa‘id said: “Her [poems] are not written in such a way that could have been addressed to a human being.”35Abdul Rahman Jami, Nafahat al-uns (Tehran: Ketabforushi-ye Mahmoudi, 1957), 629.

Both Jami’s and Attar’s accounts are an intertextual rendition of their Sufi master Abu Sa‘id Abul-Khair’s brief anecdote with an emphasis on Rabe‘eh’s inherent piety. Mystic poets were masters of transforming ordinary love into an allegory for Divine love to advance their own cause and Rabe‘eh was not the only woman to be canonized by Sufi poets. In his Tazkirah- al-auliya, (Memoirs of the Saints), Attar cloaked the eight century Sufi woman, Rabe‘eh al-Adawiyya in a “veil of sincerity, burnt…Lost in union with God; that one accepted by men as a second spotless Mary.”36Farid al-Din Attar, cited in Annemarie Schimmel’s introduction to Margaret Smith, Rabi‘a the Mystic and Her Fellow-Saints in Islam (London: Cambridge University Press, 1984), xxxvi. For more information on Rabeʿeh Al Adawiya and her mythologization, see Rkia Elaroui Cornell, Rabi’a: From Narrative to Myth (London: Oneworld Academic, 2019). His treatment of Rabe‘eh directly affects her gender identity, with Attar claiming she became a man, as only men can walk the path to the Divine:

If anyone should ask me why I note her amongst the ranks of men, I reply that the master of all prophets has said, ‘God looks not to your outward appearance. Attainment of the divine lies not in appearance but in sincerity of purpose …’ Since a woman on the path of God becomes a man, she cannot be called a woman.37Farid al-Din Attar, cited in Reuben Levy, The Social Structure of Islam (London: Cambridge University Press, 1969), 132.

In Attar’s words, woman’s saintly status is measured by her chastity (virginity) and in reference her approval by the male’s gaze (maqbul-al-rijāl). Her womanhood must be first vetted before she can join the ranks of mystics—and to label her as a saint, she must be de-womanized or better yet masculinized and metamorphosized into a man.

But how did Rabe‘eh Quzdari construct her own gender identity? What answers do her remaining words contain? The corpus of Rabe‘eh’s poetry is extremely scant. The small number of lyrical poems available to us show an entanglement with the pains and pleasures of love at their core. Since the Persian language lacks gender markers, Rabe‘eh’s ‘beloved’ remains obscure in terms of sex. But from the mundane tone and linguistic references of her poems it becomes clear that she is talking about a raw and real human—not Divine—love:

My hope is that God will make you fall in love

With someone cold and callous just like you

And that you’ll realize my true value when

You’re twisting in the torments I’ve been through.38Davis, Mirror of My Heart, 6-7.

In a poetic tradition characterized by the exaltation of the beloved at any cost, cursing the beloved is a bold and subversive act. This is also a poem about revenge, turning what should be a prayer into a curse. It is raw and embodied, seething with real feeling. It is the writing of a woman with a body and a mind.

By reversing the position of the lover and beloved, Rabeʿeh subverts the conventional transaction of love in Perso-Arabic writing, where the beloved is constantly placed in a higher position. Loathing the beloved became a more common trope among poets of later eras such as Saʿdi Shirazi, Amir-Khosrow Dihlavi and Vahshi-Bafqi who occasionally wrote poems of this kind. This again confirms Rabeʿeh’s place as a poetic pioneer and a bold, unflinching voice in the canon.

Rabeʿeh refuses to beg, mourn, compromise or pursue. She breaks and leaves. In the eighth chapter of her book, Living a Feminist Life, the feminist and queer writer of color, Sarah Ahmad, defines this “feminist snap” as a “sudden break” when the woman reaches a breaking point that she cannot accept. To snap is to speak up, to take action, to refuse to accept unacceptable interactions.39Sarah Ahmad, Living a Feminist Life, Ch. 8. Rabeʿeh speaks up, takes action and refuses the unacceptable behavior of her beloved all in one short poem. This is not the voice of a mystic or a shallow coquette.

In another short poem, Rabeʿeh celebrates the physical reunion with her beloved:

I am drunk with love to know my love is here tonight

And that I am freed from sorrow and from fear tonight;

I sit beside my love, and earnestly I say,

“God, make the key to morning disappear tonight!”40Davis, Mirror of My Heart, 6-7.

This poem takes place behind the closed doors of the night and in the beloveds’ physical presence. Physical reunion in a dark night eroticizes the love affair. There is no reference to a place or a location where this reunion takes place which adds to its secretive quality and perhaps spatial precarity too. It is night, and as she is seated by her lover’s side, Rabeʿeh speaks to God and asks for a miracle: “to make the key to morning disappear.” Speaking with God face-to-face in the darkness of the night, body-to-body with the beloved, is the subversive gender that Rabeʿeh constructs for herself. The erotic referentiality of the image codes throw light on the poet’s gender identity as a lover who first invites the gaze, only to forbid its entry until the arrival of morning.

Finally, Rabeʿeh most well-known and frequently referenced poem is a short lyric poem about love which recounts the poet’s personal experience of falling in love and facing its afflictions:

His love has caught me once again-

I’ve struggled fiercely, but in vain.

(Well, sobersides, explain to me

Just who can swim love’s shoreless sea!

To reach love’s goal you must accept

All you instinctively reject-

See ugliness as beauty, eat

Foul poison up and call it sweet.)

I jerked my head to work it loose

Not knowing all this would produce

Was a further tightening of the noose.41Davis, Mirror of My Heart, 6-7.

Rabeʿeh is the pioneering figure in coining the metaphorization of love as a “shoreless sea” which later became one of the central metaphors of mystical literature with frequent appearances in the poetry of Sanai, Attar, Mowlavi, and Hafez. This is another example where we can see Rabeʿeh break ground in shaping the poetic lexicon, becoming a model of emulation in her own right—a far cry from the denigration of court women poets slammed for writing weak derivatives of male poetry. She also leads the way in defining the lover’s duties in the face of upheavals, a role that was later reserved for the masters of didactical Sufi literature. To act against one’s desire in search of Truth became the pinnacle of mystical thought in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Rabeʿeh planted the seed for this all-consuming type of love and singlehandedly set the tone for an emerging all-male mystical tradition whose main objective was the reconceptualization of nothing but love.

The ending lines of the poem are key in the characterization of this love. She reappears at the end of the poem in the body of an untamed, wild horse (asb-i vahshi). “Tusani kardan” or ‘to behave like a wild horse’ is Persian expression for unruly, rebellious behavior. In this context, it is a reference to acts of transgression in love as a result of which the speaker has reached a point of no return—her own death. The confessional tone of the last line reifies the abstract conceptualization of love in the previous lines. Transgression itself is the core in this poem. In constructing her own gender, Rabe‘eh depicts herself as a rebellious lover who has violated the rules and conventions of the social order regardless of its outcome.

Forugh Farrokhzad’s well-known poem, “Sin” (Gunāh), written some thousand years later, is the continuation of the same act of transgression, albeit in a much more erotic and personified poetic language. If Rabeʿeh forged the path of transgressive love, Forugh carried that path to fruition by expanding the semiotic language to write against the abjection of the feminine and corporeality of her love affair:

I have sinned a rapturous sin

In a warm enflamed embrace,

Sinned in a pair of vindictive arts,

Arms violent and ablaze.42Forugh Farrokhzad, “Sin”, translated by Dick Davis, Mirror of My heart, p.366-367

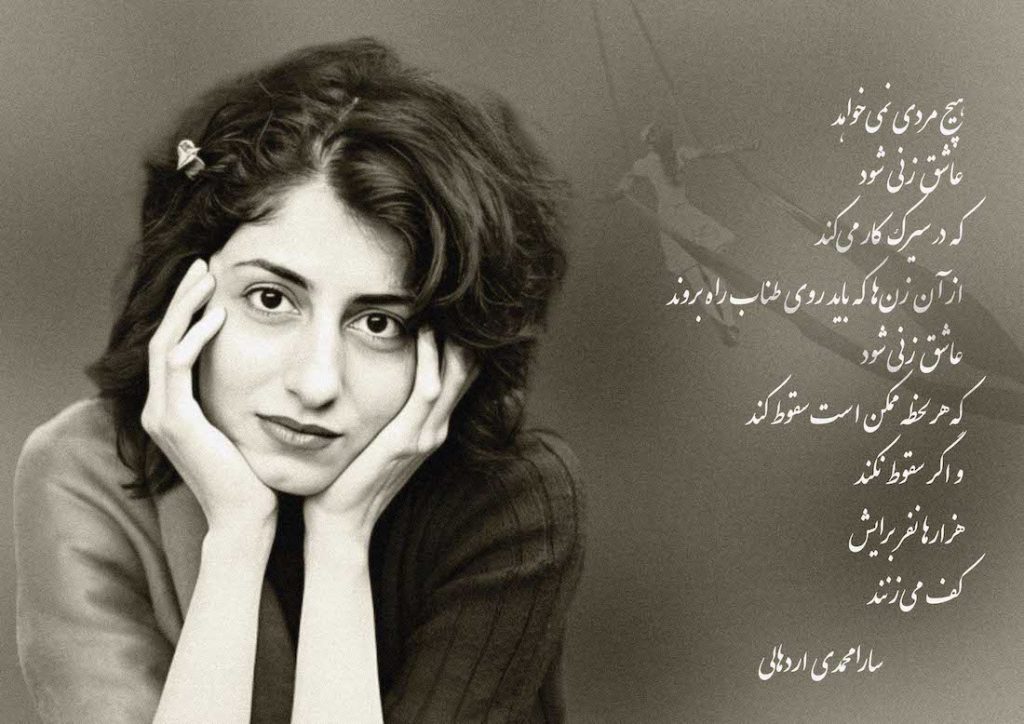

Years after Forugh, women poets continue to depict women’s gendered displacement in an unparalleled fashion. The following poem, titled “A Full-time Position” (Kār-i tamām vaqt) by Sara Mohammadi-Ardehali (b.1976), is a prime example of such poetry:

No man wants

To fall in love with a woman

Who works in a circus

One of those women who has to walk a tight-rope

To fall in love with a woman

Who might fall at any moment

And if she doesn’t fall

Thousands of people clap their hands

To applaud her.43Forugh Farrokhzad, “Sin”, translated by Dick Davis, Mirror of My heart, p.366-367

Stuck on a tight-rope, the woman continues to exist, and perform, in the most precarious position under the envious gaze of patriarchy. She is too proficient and visible to be loved. She is that rare female species that Aufi would not expect to exist. Mohamadi-Ardehali masterfully depicts women’s gendered personhood and displacement in a patriarchal economy where even a full-time position for the woman comes with its own risks and problems.

Concluding Remarks

To return to the opening question: What is a woman poet? We began with the simple definition—woman who writes, who breaks through patriarchal structures to be published and read. As we have seen, the category of ‘women poets’ as a gendered class is united by this definition—but also by much more. Those who find themselves in the category of women poets have been forced to accept a Faustian pact in which, in exchange for their words, they give up control over how their bodies and biographies are perceived and documented. They enter into a canon in which they can either have minds—and be elevated into mysticism—or bodies, and be fetishized as lustful boy-chasers. The label ‘woman poet’ does not necessarily enable the writer to be either fully woman or fully poet; instead, they are consigned to a judgmental half-life, in which their human actions and creative output merge and undermine one another.

To find new ways of understanding, reading, and theorizing women poets, we need to plant seeds of doubt in their representation and canonization as the first step to move away from rigid binary classifications that further marginalize women as a minor literary category. Women’s poetry can only exist as a meaningful category if it is not considered to be a self-evident binary that must constantly reposition itself within the landscape of male poetry in order to exist. If we accept Butler’s conceptualization of gender as an evolving construct which moves further away from the feminine/masculine binary, we must begin to explore the gendering process by reading their own poems through a theoretical lens.44Susan Brown sets forward a useful conceptualization of the category of “poetess” in her article about Victorian poetess. See, Susan Brown, “The Victorian Poetess,” in The Cambridge Companion to Victorian Poetry, ed. Joseph Bristow (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 184-186.

In re-reading Rabeʿeh’s poems we can trace a dynamic gender identity that shines through her transgressive approach to the physicality of love without fetishization of a gendered body. We can observe how she constructs her own gender through performativity. She constantly writes herself into language either face-to-face with God, body-to-body with the beloved, or places herself in an insubordinate, defiant position of a lover that disrupts any form of passivity, absence, and abjection in the social order.

Definitions and delineations—reductionist as they may be—can be useful. They can supply the much-needed remedy to entrenched invisibility for the unheard and unseen. The tokenistic and misleading genderization of the Persian literary canon has so far been unhelpful, but it is a sign of progress that more women poets are being published and known—that contemporary voices are increasingly able to defend, reject, and speak out on the labels they are given.

Behbahani’s ‘drawn curtain’ has begun to open, and while women poets are still too often in the ‘wrestling ring’, perhaps now they are pulling punches of their own. We are a long way from Farrokhzad’s belief that “The most important thing is to be Human (Ādam)”; but as writers, as anthologizers and commissioners, as academics and theorists, we have the opportunity now to begin to correct that balance.

![Fatemeh Shams Photo 2 [FS]](https://poets.iranicaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Fatemeh-Shams-Photo-2-FS-150x150.png)