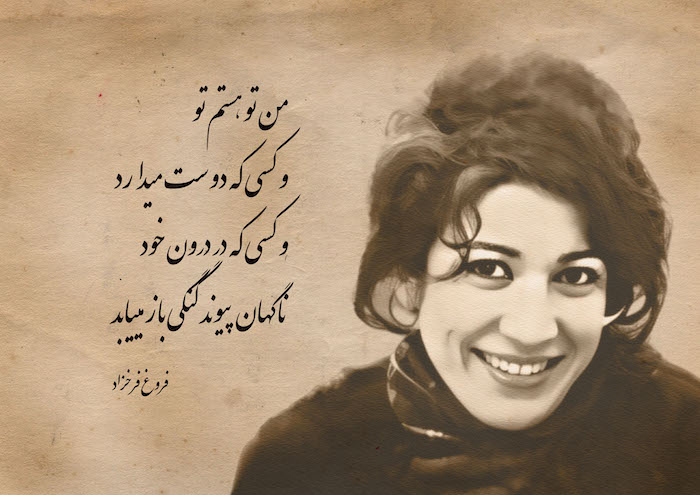

Of the Sins of Furūgh Farrukhzād

“Sin” (Gunah) is probably the most well-known poem of Forugh Farrokhzad, though it is not one of her best, even in comparison with most of the poems before the period of Another Birth (Rebirth). Apparently a defiant declaration of feminist independence, a closer examination of that and some other early poems betrays a sense of guilt, bewilderment, and remorse. It is in the later poems, and especially those of the period of her “rebirth,” that “pleasure” gives way to acceptance, and “sin,” to real self-assertion and self-confidence. Nevertheless, analyzing her published letters, and especially the two long letters to her father, it will be argued that, in spite of the upward journey both in love and poetry, the poet’s longing for deep fulfilment remained frustrated until the very end.

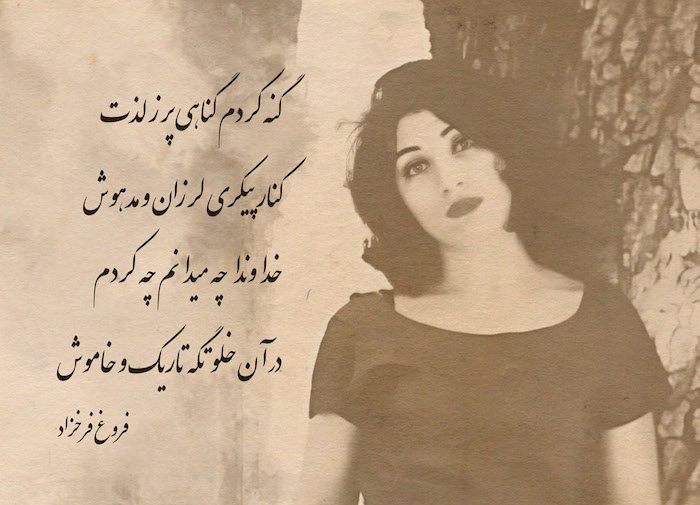

“Sin” is one of the earlier poems that openly describe a carnal engagement, though not the first one. Its enormous impact on readers and critics in and outside of Iran is due to its apparently vocal, almost proud, defiance against the social conventions and the condemnation that the poet knew to be mandatory for committing such sins, especially if the ‘sinner’ was a married woman. Otherwise, the artistic value of the poem is considerably lower, not only than all the poems she was to publish after her “rebirth” but of most of the earlier poems as well. This is best appreciated when the poem is read in the Persian original, it being possible to camouflage, misinterpret, explain away, or mystify the weaknesses of form and substance in English translation. It is a simple poem, describing a sexual experience in the form of connected doublets in six short stanzas, involving some repetition, and employing commonplace or unlikely figures of speech and literary devices. The poem opens with its first doublet or stanza:

I sinned a sin full of pleasure

in an embrace that was warm and fiery.

I sinned wrapped in arms

that were hot, vengeful, and made of iron.1Forugh Farrokhzad, Divar, 3rd printing (Tehran: Amir Kabir, 1969), 13. For a somewhat different translation which makes the poem look more elegant in English, see Zjaleh Hajibashi, “Redefining ‘Sin,’” in in Forugh Farrokhzad, A Quarter Century Later, ed. Michael Craig Hillmann (Austin, Texas: Literature East &West, 1987), 68. Another translation may be found in Another Birth, Selected Poems of Forugh Farrokhzad, trans. Hasan Javadi and Susan Sallée (Emeryville, CA: Albany Press), 11.

Describing something fiery as warm and then calling it hot is not very elegant. In fact the word “warm” is completely redundant and has been necessitated by the need to make up the metre in the Persian original, the metre being that of fahlaviyat: mafa’ilun, mafa’ilun, fa’ulun, as in Baba Taher’s doublets (taranahs).2Gunah kardam gunahi por ze lazzat / Dar aghushi kih garm o ateshin bud. Here the word garm is completely redundant and has been used to make up the metre. See Farrokhzad, Divar, 13. Other formal weaknesses may be shown in this short poem especially if the Persian original is scrutinized: this is a short and defiant declaration of the commitment of a “sin” which could well have been made in prose, its only poetical feature being versification by metre and rhyme which are made up by the use of any and all words and phrases such as “My heart impatiently trembled in my chest (dilam dar sinah bitabanah larzid).”

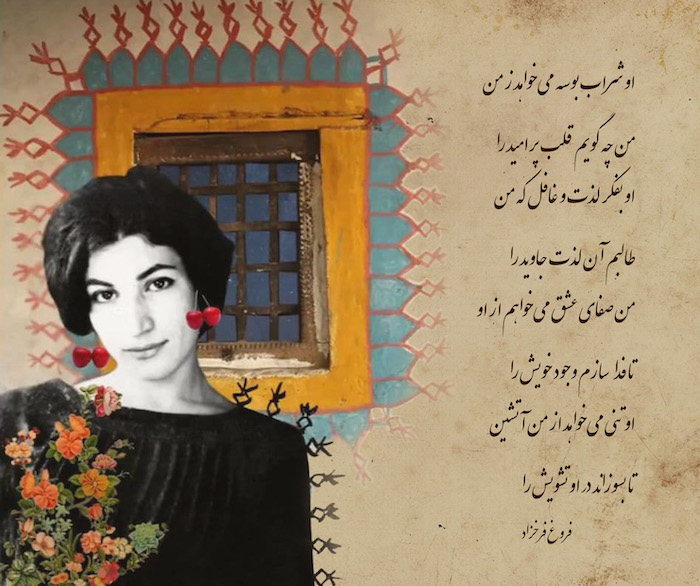

This is a relatively early poem, written long before Another Birth, but the poet was writing far more sophisticated poetry before and at the time of writing it. Take for example the poem “The Kiss” (Busah) which had been published in the earlier volume (The) Captive, and ends with the stanza:

A shadow leaned over a shadow

In the secret hideout of the night

A breath brushed over a cheek

A kiss flamed up between two lips.3Forugh Farraokhzad, Asir, 3rd printing (Tehran: Amir Kabir, 1963), 29. For a somewhat different rendering, see Bride of Acacias, Selected Poems of Forugh Farrokhzad, trans. Jascha Kessler with Amin Banani (Delamar, New York: Caravan Books, 1982), 125.

There can be many more examples—e.g., “Shab va havas,” “Hasrat,” “Mihman,” etc., all of them from the collection Captive—to show that “Sin” is a weaker poem than many that Farrokhzad had written before, or about the same time.

In fact, it may be argued that the formal weaknesses of “Sin” are not unrelated to the substance, where a sense of guilt and remorse is camouflaged by a brave gesture of defiance. The poetical voice which is unmistakably that of the poet herself confesses to what she herself describes as a sin; and it ends the short poem by repeating the confession, and remorsefully addressing God, saying:

I sinned a sin full of pleasure

beside a body, trembling and unconscious.

O’ God I know not what I did

in that dark, silent, secluded place.4Farrokhzad, Divar, 15.

The key words in the poem are sin and pleasure. The poem displays anger and defiance, but it also reflects doubt and uncertainty. And it describes no more than a feverish physical experience resulting in pleasure. The confessor has sinned involving much pleasure, rather than giving herself up in a loving relationship resulting in a sense of liberation. This may be contrasted with an earlier poem which reads:

He wants the wine of kiss from me.

What shall I tell my hopeful heart?

He is thinking of pleasure, unsuspecting

that I want the pleasure which is eternal

I want sincere love from him

so I could sacrifice myself.

He wants a fiery body from me

in which to burn up his anxiety.5Farrokhzad, “Na-ashna” (Stranger), in Asir, 31.

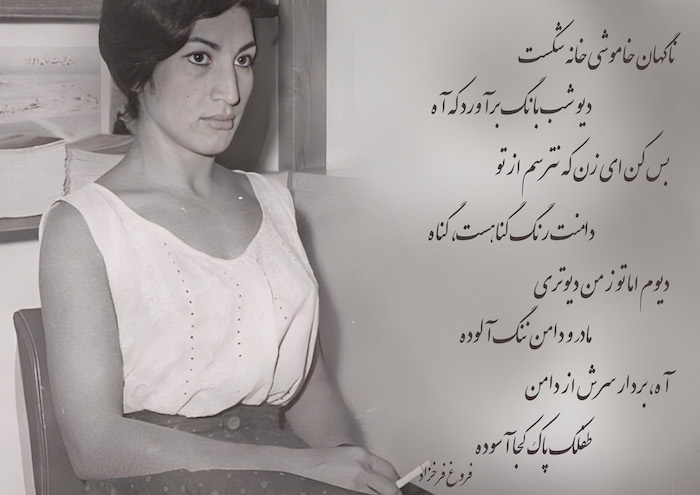

But the expression of guilt and remorse is familiar from other poems of this period. For example in the poem “Tramp” (or Whore; Harjā’i), the title of which alone confirms society’s judgement:

You came late when I had lost control.

You came late when I was drowned in sin,

when by the whirlwind of wretchedness and infamy

I had been extinguished and ruined like a candle.6Farrokhzad, “Harja’i” (Tramp), in Asir, 24.

In the poem, “Demon of the Night” (Div-i Shab), the mother is saying a lullaby for her infant son, warning him of the ill-intentions of the demon of night, who later comes to snatch the baby away and is defied and abused by the mother:

Suddenly the silence broke

the demon of night shouted

Stop woman, I am not afraid of you

your lap is tainted by sin, by sin.

I am a demon but you are worse than me

being a mother, but tainted with the shame of sin.

Take your baby’s head off your lap!

That is no place for the innocent babe to rest.

The mother accepts that judgment, and says with a burning heart:

I moan O’ Kami, Kami

Take your head off my lap.7Farrokhzad, “Div-i Shab,” in Asir, 51-3. Kami is short for Kamyar, the name of the poet’s son.

Thus, it is clear that the statement issued in the poem “Sin,” although it is daring and rebellious, is the other side of the coin to such other poems as “Tramp” and “Demon of Night.” Except that in “Sin,” the poet has had enough of the prevailing social judgements, which she herself also accepts, and so loses patience and shouts: I sinned, a sin full of pleasure! And it is precisely this sloganeering style of the poem that makes it look like a versified statement confessing to a sin. Whereas, as I shall try to show below, in her later poems, and especially those written in the period of Another Birth (or Rebirth), sin and pleasure are replaced with profound love and self-assured submission to the beloved, although love itself is never quite realized and the search for it continues until the end of the poet’s short life.

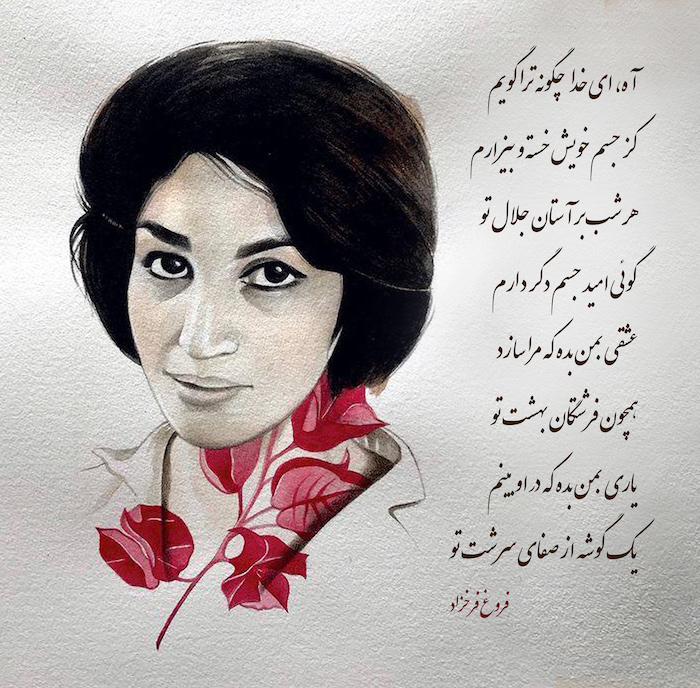

Before doing that, however, it is worth mentioning a poem the significance of which has seldom been acknowledged in Persian or English studies of Farrokhzad’s works. Made up of eleven stanzas, this longish poem—“Dar barabar-i khuda” (In the Presence of God)—is addressed to God, pleading with him to forgive her sins, and speaking of hating her own body:

O’ God how can I tell you

that I am tired of and disgusted with my body.

Every night at the threshold of your splendour

it looks as if I wish for another body.

Give me a love that would make me

just like the angels of your paradise.

Give me a lover in whom to see

an example of the purity of your nature …

O’ God whose strong hand

has founded the world of being

Show your face and take from my heart

the zest for the sin of selfishness …8Farrokhzad, “Dar Barabar-i Khuda,” in Asir, 111-14.

This hatred of her body completely disappeared in the latter part of Farrokhzad’s life and work, and gave way to self-confidence, acceptance, sublime experience, as well as a search for a love that was never realized, and in fact would have been very unlikely to be realized, as it was chasing after an illusion. A long letter by Farrokhzad to her father, published relatively recently, throws considerable light on herself and her poetry. It was sent from Munich to Tehran and written on 2 January 1957, shortly before Farrokhzad turned twenty-two. It is strangely reminiscent of Kafka’s famous piece, “Letter to His Father,” although Kafka’s letter was dressed up as fiction and was never actually sent to a father from whom he was so alienated and of whom he had been so much afraid in his childhood.9See for example, Eric Heller, Kafka (Fontana: London, 1974). Farrokhzad’s letter too shows the great distance as well as conflict between her and her father, the extent to which she was frightened of him and felt humiliated by him, and how she had felt to be a stranger in her paternal home. She says that if she wrote all that she wanted to say it would fill a whole book and make her father unhappy, “but I too cannot feel peace and contentment until I have told you all that is in my chest; and, being with you, try to be myself, rather than a being who neither laughs nor talks, and can only sink into herself and stick to a corner.” And she goes on to add:

My greatest pain is that you never got to know me and never wanted to know me. I remember when I used to read philosophical books at home … You would judge me by saying that I was a stupid girl whose mind had been poisoned by reading journals. I would then fall into pieces inside myself, tears coming to my eyes for being so much a stranger at home, and sulk … And there are a thousand other cases like this … every one of which will be enough to break the spirit of an individual.10See Dar ghurubi-i abadi, ed. Behruz Jalali (Tehran: Morvarid, 1997), 108. This particular letter (alongside a few to others) has also been published in Zani tanha, Yadnamah-yi Forough Farrokhzad, ed. Hamid Siyahpush (Tehran: Agah, 1997), 210-14.

She goes on to explain that many a time when she had committed an “error” (khata) she would have wanted to tell her father and seek guidance from him but that “as ever” she had been afraid of him. Here she is referring to when she had been a girl living at home. Since then, she had married, divorced with a little son and—after a short while when due to a clash with her father she had lived in a little rented room in a corner of town—she had been reconciled with him and returned home, only to face the same old regime. Thus she wrote that even then, many a time when she had been trembling with remorse and regret for an “error” which she had committed and wished to talk to her father and seek advice, “I was as ever afraid and felt that I am a stranger to you.” And she goes on to add:

Whenever I think of last year living at your house my heart sinks. I did everything, both good and bad things, secretly, just like thieves. Why did you lack respect for me, and why did you make me keep away from home, and just like a sleep-walker, not to know where I am, what I do and whom I am talking to … And inevitably I used to commit errors, many errors.11Jalali, Dar ghurubi-i abadi, 110.

She points out bluntly that contrary to her father’s belief she is not a street woman (zan-i khiyabangard), and now that she lives independently, “and no one looks at me with hatred and contempt,” she will take responsibility for her actions and would never forgive herself for making a mistake, although she does not blame herself, but “others” instead, for her past mistakes.12Jalali, Dar ghurubi-i abadi, 112. She speaks of her intense suffering, feeling as if she is buried in a grave, and finally begs her father not to break his relationship with her again, and love her as he does his other children. This shows that despite her sense of a new-found freedom, independence, and personal responsibility, she is still deeply involved with her father and longs for his approval. She expresses regret that she cannot tell her father all that she wants to tell him, beginning with her childhood, because she is afraid that it might upset him. Yet she repeatedly says that she loves her father and wishes that he love her too, and even thanks him for the monthly allowance he was sending her from Tehran. But at the same time she does not tire of repeating how fearful and alienated she is from him.13Jalali, Dar ghurubi-i abadi, 112.

Whatever Freud, Jung, Adler, and others might have done with material of this kind is a matter for speculation, though not very difficult to imagine. What is patently obvious is the strong sense of alienation that Farrokhzad feels from her father, while at the same time desperately longing for the gap between them to be closed and be turned into love and understanding. As will be noted below, it is this newly acquired sense of freedom, independence, and responsibility, that shortly results in her rebirth in life as well as poetry, and closes the seasons of “pleasurable sins,” “errors” and “mistakes” combined with guilt, regret and self-reproach.

In an earlier letter to her father, written also from Germany, Farrokhzad declares that she has no worldly ambitions, that poetry is her god, and that if she loses the ability to write poetry she will commit suicide: “Let others regard me as an unfortunate and wandering person, but I shall never complain about my lot…I sometimes wonder why God created me as I am, and brought to life in me this devil that is called poetry, so I would not be able to gain your approval.”14Jalali, Dar ghurubi-i abadi, 113. This earlier letter is also published in Zani tanha, 209-210. But writing poetry, not pursuing formal education, and not seeking social success were some, not all, of the apparent causes of her father’s strong disapproval of her. It was her entire mode of living, and as a part of it her marriage and divorce, and what he described as her “being a street woman.”15Jalali, Dar ghurubi-i abadi, 109.

It is clear from her letters that she wishes to have, if not her father’s love then at least his acceptance of her life style. That is, although it is easy to observe her anger (both at this stage and previously ) with her father—and it is explicit in some of the letters which she later wrote from Germany to her brother Fereydun in Tehran16Jalali, Dar ghurubi-i abadi, 115-22.—it is also evident that she wishes, perhaps even more strongly, that there had been a bond of love between her and her father from the beginning, and that at least such a bond may be established from now on. The love-and-hate syndrome is of course something almost commonplace.

Thus we observe that since her childhood the poet has been longing for her father’s love and that she had never found it by the time she wrote those letters to him; and not even later, when in 1959 we find her writing from Tehran to her brother Fereydun in Munich: “It’s only possible to say ‘hello’ to father.”17Jalali, Dar ghurubi-i abadi, 119. This was not a mere lack of kindness which it is clear from the letters had existed between father and daughter, at least from time to time. On the contrary, it was a deep-seated problem which, in the case of the daughter, went back to the distant past, and its roots were to be found only in the depths of her unconscious. On the basis of this evidence and more from all of her published letters, it is not difficult to imagine the motive for committing those “sins” (as she calls them in her poems) and “errors” (as she describes them in her letters to her father), a desperate search for the love of her father, each time ending with failure and remorse.

It is clear from Farrokhzad’s life and works that she was constantly looking for a ‘paradise lost’ or at least not yet gained. And that the paradise that its seeker had in mind was a perfect object which, by definition, was unattainable. Someone or something might suggest themselves from time to time as the perfect object and so would make the seeker stop looking for a while, but sooner or later this would come to an end, since they could not quench the seeker’s thirst for that which was pure and flawless, allowing her to drown herself in it and bury her obsessions and “sins” in a sea of absolute security and certainty, absolute and unqualified love. Hence, Farrokhzad was caught between God and the devil, faith and “sin,” unattainable love and the “errors” she committed in her attempts to find it. Therefore in her own words she became “lonely,” and in the hope of combating loneliness, she sought asylum in her poetry, and turned it into a god, which although it did not quite replace the perfect object, it was nonetheless the most certain and secure substitute for it: “poetry is my god”; “If I lose the ability to write poetry I will commit suicide.”18Jalali , Dar ghurubi-i abadi, 113; Zani tanha, 210.

Both Kafka and Hedayat eventually became literature itself, not because there was nothing left that they wished to possess, but because in their desperate search for that unknown and unattainable object, their bodies and souls turned into pure literature. And, in this sense, their literature was a product of the great suffering which they experienced, the only benefit of which for themselves was its use as a substitute for the lost paradise. However, and precisely because it was not the perfect object itself, but a mere substitute, it did not quite quench their thirst, and in other ways even exacerbated their predicament. What we observe in Farrokhzad’s life and work is not far removed from their experience.19See further Homa Katouzian, Sadeq Hedayat: The Life and Legend of an Iranian Writer (London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2002); “The Wondrous World of Sadeq Hedayat,” in Sadeq Hedayat, His Work and His Wondrous World, ed. Homa Katouzian (London and New York: Routledge, 2008); Eric Heller, Kafka; The World of Franz Kafka, ed. J. P. Stern (London: Weidenfeld and Nicloson, 1980); Ernst Pawel, The Nightmare of Reason: A Life of Franz Kafka (London: Collins Harvill, 1988).

In a letter to her brother Fereydun composed two years after the letters to her father, Farrokhzad wrote:

Here [in Tehran] I am very lonely. I work like a dog to compensate for loneliness. I’ve made a documentary film about the life of lepers which has been successful … Such is life.

[But whatever you do] you are in any case lonely, and loneliness devours and breaks you. I look terribly aged and my hair has gone gray and I find the thought of the future suffocating.20Jalali, Dar ghurubi-i abadi, 116-17.

The letter dates to the beginnings of the latter part of her short life, that of “rebirth” (or another birth), both of herself and her poetry. As we shall see, from then on, there is no more talk of “sin,” “error,” remorse, and regret. Yet the basic problem, the deep yearning for the unattainable love, the lost paradise, remains until the very end. For example, in a series of letters to Fereydun, written mostly in 1959, the first year of her “rebirth,” she writers that she is a “rootless person and it is only my loving (dust dashtan-i man) that sustains me, but what’s the use … Oh my dear Feri I don’t know why I am writing all this, but I am unhappy … unhappy, unhappy, and I am very lonely here.”21Jalali, Dar ghurubi-i abadi, 118-19. And in another letter:

I am very unfortunate, my dear Feri, and no one knows. Even I myself don’t want to know it. Because when I come face to face with it the only thing I can do is to throw myself out of the window … Oh, I’m writing rubbish.22Jalali, Dar ghurubi-i abadi, 119-120.

In a letter dating from a couple of years after the onset of her “rebirth,” which coincided with an apparently fulfilling and long-lasting relationship, Farrokhzad writes to her partner: “I feel as if I have lost my life.”23See Amir Esama’ili and Abolqasem Sedarat, Javidanah Furugh Farrukhzad (Tehran: Marjan, 1968), 14. And in another letter to him, in a poetical description of the acute thirst which she feels in the depths of her soul for the lost object: “I feel a confusing pressure under my skin … I want to drive a hole in everything and sink down as far as possible. I want to reach the depths of the earth. My love is there.”24Esama’ili and Sedarat, Javidanah Furugh Farrukhʹzad, 14.

And in yet another letter to her partner, Farrokhzad reflects on the inner anxiety which is essentially a product of loneliness, insecurity and alienation, by saying “I have always been like a closed door so that no one would see and recognize my terrifying inner life.”25Esama’ili and Sedarat, Javidanah Furugh Farrukhʹzad, 14. And in the next letter she writes: “I don’t know what it means to arrive, but it must be an end towards which the whole of my being moves”26Esama’ili and Sedarat, Javidanah Furugh Farrukhʹzad, 14.; to which she might have added, ‘and I am afraid of never making it’. In the following letter it is almost as if it is Hedayat, in his psycho-fictions and letters, who is judging “a world where as far as one can see there is wall after wall after wall, a rationing of sunshine, and a famine of opportunity, and fear, suffocation and abject existence.”27Esama’ili and Sedarat, Javidanah Furugh Farrukhʹzad, 15. And finally she writes: “I am happy that I am no longer idealistic and dreamy. I am about to become thirty-two … But at least I am happy that I have found myself.”28Esama’ili and Sedarat, Javidanah Furugh Farrukhʹzad, 16.

And when Farrokhzad died, she was just thirty-two. But the claim of not being dreamy anymore and having found herself, though it does reflect psychological development, refers only to the poet’s consciousness, not what lurks beneath it in her unconscious. This may be discerned, for example, from one of her last poems “Someone Who is Not Like Anyone Else’ (Kasi kih misl-i hich kas nist), written shortly before her death:

Why am I so little

that I get lost in the streets.

Why does father who is not so little

and is not lost in the streets

not do something, so that the person whom I have seen in my dream

brings forward the day of his coming.

And after she says that she has “swept the stairs going up to the rooftop” and “has washed the windowpanes,” Farrokhzad asks, “Why should father dream only when he is asleep.” It is at this point that she says:

Someone is coming.

Someone who is with us in his heart, with us in his breath, with us in his voice.29See Furugh Farrukhzad, “Kasi kih misl-i hich kas nist,” in Iman biyavarim bih aghaz-i fasl-i sard [Let Us Have Faith in the Onset of the Cold Season], 9th printing (Tehran: Morvarid, 1991), 80-8. I have benefitted from the following English translation, but the rendering in the text is my own: “One Like No Other,” trans. Kessler with Banani, in Bride of Acacias, 112-15.

This is the one who does not look like anyone else, the unattainable hero who can only be seen in a dream. The poem ends with the words “I have had a dream …”

Two layers may be distinguished in this poem, the apparent layer, which prophesies the advent of a messiah, a saviour, and the less obvious but a probably more real one, promising the coming of the poet’s own messiah, the lost and longed for hero, both of whom, incidentally, belong to the perfect time-space.

Nevertheless, the continuing development which was noted to have taken place at the level of consciousness is real, and its signs may be seen in the very poems of Another Birth and after. And the real “rebirth” is precisely in such developments that take the substance of Farrokhzad’s poetry up to a different plain, and significantly influence their formal qualities, the imagery, the metaphors, and other literary devices. Otherwise, the “rebirth” would not have happened just by using broken (sometimes called Nima-esque) metres or, in the end, free verse.

To demonstrate the point, the poem “Sin,” written at twenty, may be compared and contrasted to one of the early poems of the Rebirth period, not a very well known one, written at twenty-five and titled, “In the Cold Streets of Night,” which opens with the following verses:

I am not remorseful.

I am thinking of this submission, this painful submission (taslim).

Contrast “I am not remorseful” in this poem with “I sinned,” the opening verse of “Sin,” since both poems are apparently telling a similar story, though in fact the stories are quite different. This time there is no defiant confession of a sin, nor is there any self-doubt, any regrets, for what has happened. It is a submission, “a painful submission,” by a self-confident lover who has had the courage to take responsibility for her action, who is not remorseful, and who does not address God in embarrassment. Her will is much stronger in surrendering herself here than in committing that sin there. Therefore, there is no talk of pleasure but a self-sacrifice which is the very essence of her satisfaction:

I kissed the cross of my fate

on the hills of my killing ground.

This is an allusion to the Crucifixion, a metaphor for being willingly sacrificed. Incidentally, the much higher quality of form in this poem over “Sin” is evident, especially in the Persian original, it being not so much because the equal quantitative metre has been abandoned for a broken metric structure, but especially because of what is being said in the new form.

The poet or poetical voice keeps repeating that she has no regrets, because she was quite sure of what she was doing, having taken responsibility for it and having consciously kissed her own cross. Hence there is no distinction between her and her lover, and no mention of his “hot,” “vengeful” and “iron” “arms,” as there was in “Sin”:

I am you, you

and the one who loves

and the one who suddenly finds

a vague connection within herself

with thousands of unknown, unfamiliar things.

Thus we observe that the “pleasure” of that “sin” has given way to this “submission” of “the one who loves” and to a vague connection to thousands of unfamiliar things. And, as noted above, if the issuing of the statement about that “sin’” and that “pleasure,” rather than showing real courage, was a smokescreen for covering the person’s self-doubt, the description of the latter experience certainly reveals her uncompromising boldness and self-confidence:

And I am the entire fervent passion of the earth

that draws all the waters into herself

to make all the plains bear fruit.30See Furugh Farrukhzad, “Dar khiyaban-ha-ya sard-i shab’ in Tavalludi digar, 4th printing (Tehran: Morvrid, 1969), 83-6. I have benefitted from the three following English translations, but the rendering in the text is my own: “In Night’s Cold Street,” trans. Kessler with Banani, in Bride of Acacias, 49-50; “In the Cold Streets of Night,” in A Rebirth: Poems by Foroogh Farrokhzad, trans. David Martin (Lexington: Mazda Publishers, 1985), 43-6; and “In the Cold Streets of Night,” trans. Javadi and Sallée, in Another Birth, 42-3.

This time the waters are sucked in, not for a passing pleasure but for impregnating the bond of love. Such is an example of that psychological-cum-literary development that apparently began to show itself suddenly with the onset of “rebirth,” resulting, among other things, in a spiritual union, in love rather than sin and pleasure. Thus, the emergence of the roots of her erstwhile pleasure-seeking and ‘sinfulness’ in the shape of direct yearning for perfect and unconditional love, for which she is ready to be sacrificed.

Yet, highly important though it was, all this change occurred, as noted, at the conscious level, while the fruitless search for the perfect hero, for the unfulfilled love of childhood which gave rise to the unattainable soulmate, remained until the very end. There is much evidence for this from the poems of the period of “rebirth.” Here I shall quote a few verses from the poem “Let us Have Faith in the Onset of the Cold Season,” one of the last which she ever wrote, and which, together with a few others, was published posthumously:

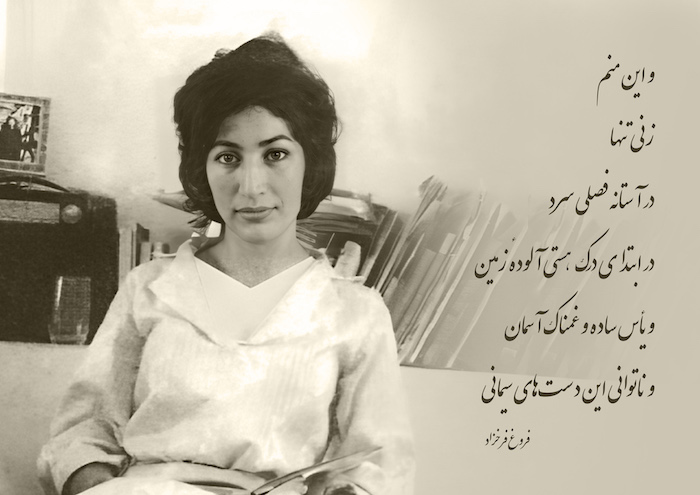

And this is me

a lonely woman

on the threshold of a cold season

at the beginning of conceiving

the contaminated existence of the earth

and the simple and sad despair of the heavens

and the helplessness of these granite hands …

That is how this long and fascinating poem opens, reflecting its author’s thought processes. In it she repeats that she is cold, cold, cold, and that she is naked, naked, naked, going on to say:

And all my wounds are due to love

to love, love, love …

I told my mother: ‘It’s all over now’.

I said: ‘It always happen before you think.

We must put our condolence letter in the newspaper.’

Greetings, O strangeness of loneliness

I surrender the room to you

because it is always the dark clouds

that are the prophets of new verses of purification.

And in the martyrdom of a candle

there lies a luminous secret

that is known by that final and tallest flame …

That is how the voice of this poet, which, beginning with a relentless search for an unfulfilled love, the longing for which had been with her from childhood, sought asylum to anywhere and anything—from a prison to a wall, from a sin to a pleasure, from this demon to that god—after untold and immeasurable sufferings reached maturity in surrender and sacrifice. And yet, failing to realize that unattainable perfect object, at least in her own honest belief, she joined the order of the martyrs: “And in the martyrdom of a candle / there lies a luminous secret /that is known by that final and tallest flame.”31Furugh Farrukhzad, “Iman biyavarim bih aghaz-i fasl-i sard,” in Iman biyavarim bih aghaz-i fasl-i sard, 23-43. I have benefitted from the following three English translations, but the rendering in the text is my own: “Let Us Believe in the Oncoming Season of Cold,” trans. Kessler with Banani, in Bride of Acacias, 95-102; “Let’s Bring Faith to the Onset of the Cold Season,” trans. Martin, in A Rebirth, 113-22; “Let Us Believe in the Beginning of a Cold Season,” trans. Javadi and Sallée, in Another Birth, 65-76.

And this she discovered when she had reached her tallest flame.

Cite this article

Furrugh Zaman Farrukhzad (born Tehran, 1935—died of injuries sustained in a car accident in Tehran, 1967) was the most prominent 20th-century Iranian poetess, feminist, and filmmaker. Many believe her to be one of the luminaries of modernist Persian literature. She was also a pioneer in Iranian new wave cinema. Famous for her subversive poetries argued to be written from the feminine point of view, Furugh’s work and her lifestyle as an iconoclast have been the center of much public attention and scholarly discussion.