Īrāndukht Taymūrtāsh: A Maternal Voice in the Making of Modern Iran

Introduction

Much of what is known about Īrānʹdukht Taymūrtāsh (1295–1370/1916–1991) comes from the influence of her father, ʿAbd al-Husayn Taymūrtāsh (1261–1312/1882–1933), who played a key role in the transition of power from the Qajar dynasty to the Pahlavi dynasty and served as Reza Shah’s first Court Minister from 1304/1925 to 1311/1932.1Rouhollah Ramazani, Iran’s Foreign Policy, 1941–1973; A Study of Foreign Policy in Modernizing Nations (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1975), 185. Īrānʹdukht is also remembered in the Iranian consciousness for the dramatic account of chasing her father’s murderer, Pizishk Ahmadī, to execution. As a result, her literary and cultural contributions as a modernist Iranian author have received comparatively far less attention.2Ahmad Ahmadī (1266/1887–1323/1944), known as Pizishk Ahmadī, served as a nurse at Qasr Prison in Tehran, where he was involved in killing political prisoners, including ʿAbd al-Husayn Taymūrtāsh, with his unique lethal injections. Īrānʹdukht successfully tracked him down in Baghdad, where he was hiding, and facilitated his extradition to Iran. After a legal trial, Ahmadī was executed on multiple charges of murdersin 1323/1944. Within the canon of Iranian literature, unfortunately, not many of her poems have been published or even preserved. However, through her contributions to women’s periodicals and her broader cultural activism, she left behind valuable textual legacies for both the women of her time and for posterity. In most compendia of Iranian women writers, compiled while she was still active in Iran, she is consistently recognized as both an orator and a poet.3Fakhrī Qavīmī, Kār’nāmah-ʾi zanān-i mashhūr-i Īrān: Az qabl az Islām tā ʿasr-i hāzir [The record of renowned Iranian women: From the pre-Islamic era to the contemporary period] (Tehran: Vizārat-i Āmūzish va Parvarish, 1352/1973), 270; and ʿAlī-Akbar Mushīr Salīmī, Zanān-i sukhan’var: Az yak hizār sāl pīsh tā imrūz kih bih zabān-i Fārsī sukhan guftah’and [The eloquent women: They have spoken Persian from a thousand years ago until today] (Tehran: Muʾassisah-ʾi Matbūʿātī-i ʿAlī Akbar ʿIlmī, 1333/1954), 15–16.

In recognition of her literary identity, I refer to her by her first name, Īrānʹdukht, rather than her family name, Taymūrtāsh, throughout this paper. Although it is common in women’s historiography for their identities and accomplishments to be mediated through the names of their fathers or husbands, I intentionally highlight her first name. Continuing to use her surname risks reinforcing the very narrative that has long defined Īrānʹdukht mainly through her father’s political legacy, rather than her literary and cultural contributions.

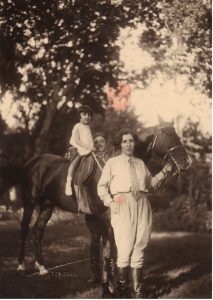

Figure 1: Īrānʹdukht Taymūrtāsh with her father, ʿAbd al-Husayn Taymūrtāsh (circa. 1310/1930)

To better understand her authorial identity beyond this inherited legacy, it is useful to situate Īrānʹdukht within her educational and cultural milieu. Īrānʹdukht Taymūrtāsh was born in 1295/1916 in Kashmar, a city in the Khorasan province of eastern Iran. She grew up in Tehran, where her father served as a cultural activist and later as a politician.4Qavīmī, Kār’nāmah-yi zanān-i mashhūr-i Īrān, 270. Her career as an author began when she enrolled at the Nāmūs School, a prestigious institution in Tehran that attracted girls from progressive Iranian families. Girls who attended this school became among the most learned women of their era, despite pressure from extremists who sought to have Nāmūs School shut down. This was in line with the school’s founder, Tūba Āzmūdah (1275/1896–1315/1936), who claimed that “women’s education was an integral part of Islamic faith, and not contradictory to its teachings.”5Helen Rappaport, Encyclopedia of Women Social Reformers (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001), 37. Later, Īrānʹdukht attended the Iran Bethel School (also known as the American Girls’ College in Tehran), which was founded and run by Christian American missionaries.

Īrānʹdukht remained influenced by the Christian domestic ideology instilled during her education, which emphasized the spiritual role of women within the private sphere but linked their feminine care to broader civilizational and national progress. Though these schools emerged from a context intertwined with imperialist logic of educating women in Islamic nations, their overriding ideology that women’s education was a vital aspect of modernization offered women like Īrānʹdukht a model of female uplift rooted in education, literacy, and domestic reform. At the same time, the portrayal of vatan (homeland) as a dying mother when she was young positioned educated women as the first pedagogues of the nation and facilitated their entry into a newly imagined public sphere.6Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi, “From Patriotism to Matriotism: A Tropological Study of Iranian Nationalism, 1870-1909,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 34, no. 2 (2002): 233. After graduating from Iran Bethel School in Urdībihisht 1309/May 1930, Īrānʹdukht gave a speech in which she described how girls like her were able to change the direction of a modern, progressive Iran by defining new social goals and enacting new forms of womanhood. Importantly, the speech was published in the journal ʿĀlam-i Nisvān, the most well-read women’s journal of the day.7Īrānʹdukht Taymūrtāsh, “Nutq-i sarkār ʿilīyyah Īrānʹdukht khānum Taymūrtāsh” [The speech by lady Īrānʹdukht Taymūrtāsh], ʿĀlam-i Nisvān 10, no. 6 (Ābān 1309/November 1930): 269–75. This helped Īrānʹdukht find herself in a more active dialogue with women of her time, particularly at a time when getting published was not straightforward or common for women, even in their own journals.8During the first Pahlavi era, much of the content published in journals exclusively tailored for women was still written by male authors as male names lent more credibility to the publication.

Prior to her father’s removal from office in 1311/1932, Īrānʹdukht is said to have been the first Iranian woman to appear in public without hijāb, particularly remembered during her graduation speech.9Masʿūd Bihnūd, Īn sih zan, Ashraf Pahlavī, Maryam Fīrūz, Īrān Taymūrtāsh [These three women, Ashraf Pahlavī, Maryam Fīrūz, ĪrānTaymūrtāsh] (Tehran:ʿIlm, 1374/1995). In the years that followed, she channeled this public visibility into activism by founding a women’s association dedicated to establishing a boarding school for destitute women. This organization remained active for several years and engaged in charitable work and educational programs, such as providing literacy classes for disadvantaged women and orphans. Building on this early activism, Īrānʹdukht pursued higher education in France and eventually earned a doctorate in philosophy from the Sorbonne University. Another point of distinction that enhanced the status of Īrānʹdukht Taymūrtāsh in the eyes of Iranians is the Legion of Honour (Légion d’honneur) medal, which she received from the French government in recognition of her cultural and philanthropic contributions. Despite these accomplishments, Īrānʹdukht has received little attention as a scholar and activist, just like many other Iranian female authors whose contributions have gone unnoticed.

Figure 2: Īrānʹdukht Taymūrtāsh

Īrānʹdukht: The Poet, The Writer

Since Īrānʹdukht’s legacy has long been overshadowed by her family’s political prominence, her literary contributions have received scant attention. The few existing sources that do mention her as an author are either limited to brief biographical notes or contain inaccuracies. One such source, for example, mistakenly identifies her as “the wife of Court Minister Taymūrtāsh” rather than his daughter.10Stephanie Cronin, The Making of Modern Iran: State and Society under Riza Shah, 1921-1941 (London: Routledge Curzon, 2003), 134. Another erroneously claims that she authored only a single short story and did not publish any other works after this, an assertion that disregards the second novella she published.11Hasan Mīr ʿĀbidīnī, “Nakhustīn gām’hā-yi zanān dar adabiyāt-i muʿāsir-i Īrān” [The first steps of women in modern Persian literature], in Markaz-i Dāʾirat al-Maʿārif-i Buzurg-i Islāmī, www.cgie.org.ir/Fa/news/9891/نخستین-گام-های-زنان-در-ادبیات-معاصرایران-(1)—حسن-میر-عابدینی. The near-total erasure of her novellas from literary scholarship has continued to obscure Īrānʹdukht’s place in the intellectual and cultural history of modern Iran. To deflect this pattern and to pay a feminist tribute to her works, I will briefly draw on her two novellas when analyzing her poetry in this paper. As Elaine Showalter notes, one of the central contributions of feminist historiography “has been the unearthing and reinterpretation of ‘lost’ works by women writers, and the documentation of their lives and careers”, a task that is especially urgent in Īrānʹdukht’s case.12Elaine Showalter, A Literature of Their Own: British Women Novelists from Brontë to Lessing (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1977), 8.

Given the erasure of much of Īrānʹdukht’s literary output, the traces that do survive acquire heightened significance. The only widely cited poem attributed to Īrānʹdukht is an elegy composed in memory of her younger brother, Mihrpūr Taymūrtāsh, who died in a car accident shortly after the family’s release from exile in Khaf, Khorasan, due to a sentence imposed on Taymūrtāsh’s family by Reza Shah and lifted following his abdication in 1320/1941.

رسید نامه منظوم و آفرین گفتم/ بدان قریحه سرشار پرشور، ترا

ستوده (فرخ) فرخنده سخن پرداز/ گزند حادثه چرخ باد دور، ترا

دلالتم بصبوری، چگونه فرمائی/ که بود آگهی از مرگ (مهرپور) ترا

بجای (مهر) نشاید گزید دیگر کس/ وگر گزینی ناید بدیده نور، ترا

زمانه ساخت مرا سوگوار در همه عمر/ نصیب ماست چنین بهره باد سوز، ترا13Mushīr Salīmī, Zanān-i sukhan’var, 16.

Your rhymed letter arrived, and I offered my praise

for that abundant, fervent gift of yours

O eloquent (Farrukh), master of auspicious speech,

may the turns of fate forever spare you from grief’s reach

How do you encourage me to be patient?

now that you are aware of Mihrpūr’s death

In place of (Mihr), who else can one ever choose?

and if you choose another, no light will ever reach your sight.

Fate has made me a mourner for my entire life

such is my portion; may such a bitter portion never fall to you.

This poem by Īrānʹdukht is very brief and might not provide adequate textual evidence for the reader to interpret much beyond an elegy in mourning for a loved one. However, considering that this is the only piece of poetry surviving from her, it deserves a closer attention and can act as a prism to interpret her broader concerns as a modernist author. Īrānʹdukht composed this poem in response to a letter of condolence from an important literary figure, Mahmūd Farrukh (1274/1895–1360/1981), who was also from Khorasan province. Farrukh had likely written to console her as she mourned the loss of her brother. In the poem, she expresses gratitude for Farrukh’s compassion and message of condolences, yet she resists his advice to be patient in the face of such grief: “dilālatam bih sabūrī, chigūnah farmāyī” (How do you encourage me to be patient?). More than being a munāzirah (conversation) between herself and the other poet, Farrukh, these brief elegiac verses are mostly dedicated to expressing her profound sense of loss as a result of Mihrpūr’s death. She emphasizes that her grief will remain with her “hamah ʿumr” (entire life), reflecting a sorrow that refuses any resolution for her. She portrays her brother as an irreplaceable soul, whose untimely death has left an enduring void in her life. The word mihr carries the dual meanings of affection or love and functions as a linguistic echo of her brother’s name, Mihrpūr. Īrānʹdukht had two other brothers, Hūshang and Manūchihr. Mihrpūr was the founder of the newspaper Rastākhīz-i Īrānand worked closely with Īrānʹdukht, who served as the chief editor of this journal, despite repeated interruptions by government censorship.14Rastākhīz-i Īrān was a leftist newspaper published between 1321/1942 and 1324/1945. Its content was highly political, and its articles reflected on global affairs, with some featuring regular columns dedicated to women’s issues. The poem transcends the conventions of a typical Persian elegy. It serves not only as a tribute to her brother’s far (virtues) but also as an expression of the care and emotional depth that defined Īrānʹdukht’s bond with her brother.

Īrānʹdukht’s feelings for her brother could also serve as a link between the elegy and her later writings in which private sorrow becomes a lens to interrogate public injustice, and the personal is turned into a didactic mode of moral instruction and collective awareness. Placed in the context of Īrānʹdukht’s broader literary work, this concern with grief and vulnerability resurfaces in Īrānʹdukht’s first published literary work, Dukhtar-i tīrāh’bakht va javān-i bu’l-havas (The ill-fated girl and the promiscuous young man), published in 1309/1930 when she was only fifteen years old. Based on a real incident in her neighborhood, the story follows a naive fourteen-year-old girl named Maryam, who is seduced by a charming but deceitful young man. After running away with him, she manages to escape and return to her family, only to be rejected by them. With no alternative, she returns to the young man and seals her fate in ruin. Īrānʹdukht herself introduces the story as a “lesson” for “inexperienced girls” who might fall victim to their emotions and jeopardize their future.15Īrānʹdukht Taymūrtāsh, Dukhtar-i tīrāh’bakht va javān-i bu’l-havas [The ill-fated girl and the promiscuous young man] (Tehran: ʿAlī Jaʿfarī, 1309/1930). The subtitle of the novel reads: Dar atrāf-i huqūq-i nisvān; Barāyiʿibrat-i khānum’hā (Regarding women’s rights; For edification of ladies), which further demonstrates her deep concerns with gender equality and reforms. Throughout the novel, she reiterates that her desire to write this story rises from the sorrow and concern she feels for her neighbor Maryam. Rather than merely recounting grief, both her poem and the story articulate an emergent feminist sensibility to loss, which is also committed to transforming that loss into a simultaneous caution and care.

Īrānʹdukht’s second and lesser-known novel, Yak pardah az zindigī-i ijtimāʿī, Khātirāt-i Ābʿalī (A scene from the social life, Memoirs in Ābʿalī), which she published in 1325/1946, still bears the mourning of her late brother. She opens the work with a dedication to Mihrpūr: bih pas-i afkār va andīshah’hā-yi ʿamalī nashudah-ʾi tu va umīd va ārizū’hā-yi nā’umīd shudah-ʾi man (to your unrealized thoughts and ideas and my ruined hopes and expectations).16Īrānʹdukht Taymūrtāsh, Yak pardah az zindigī-yi ijtimāʿī, Khātirāt-i Ābʿalī [A scene from the social life, Memoirs in Ābʿalī] (Tehran: Kayhān, 1325/1946). From this personal dedication, the novel shifts into a series of social encounters that extend her private loss into a broader critique of injustice. Set during a short trip to Ābʿalī (a countryside near Tehran), the story unfolds through her observations of the everyday lives of ordinary people in Iran. On the streets of Tehran, she notices young boys who are working for a minimum wage instead of attending school. She later meets an old friend Farīdah, whose early marriage and imposed divorce led to a life of prostitution and deprived her of parenting her only child. This novella ends with the image of a mother in poverty, unable to feed her children, not out of neglect, but because of the crushing weight of social injustice that mostly uneducated women from the lower classes of society had to deal with. Through these scenes, Īrānʹdukht applies her mourning and sorrow to a wider practice of care for women of her country, showing how the maternal sensibility that marked her grief for Mihrpūr is in fact a lens for interpreting women’s suffering in society. She weaves her private emotions into a social critique by highlighting how women, particularly as mothers, endured the burdens of a nation rushing toward modernity. These works together create a maternal-authorial figure who mourns, critiques, nurtures, and simultaneously advocates for reform through a cautionary and educational approach.

While a poem is always open to endless interpretations from its readers, the short length of Īrānʹdukht’s only surviving piece leaves very little room for close reading and textual analysis. However, this short elegy finds its meaning when read as resonating with the maternal role that many women of her generation envisioned for themselves as modern participants in the project of nation-building. Despite the persistent pressure in literary criticism to keep formalism and historicism analytically separate,17Caroline Levine, Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 14. the interpretation of Īrānʹdukht’s solo poem needs to be historicized to lead us to her broader critical thoughts as a female author in early twentieth-century Iran. By the time Īrānʹdukht composed this poem, discourses of women as mothers and healers of the nation were deeply intertwined with the task of caring for the homeland.18Tavakoli-Targhi, “From Patriotism to Matriotism,” 233. For the first time, women were given a role in the broader scheme of modernizing their country and their duties as mothers of a new emerging nation were kept abreast of men’s influence in politics. While the exact date of the elegy is unknown, it was composed after the death of her brother Mihrpūr, which occurred following Reza Shah’s abdication in 1320/1941, and during the early years of the second Pahlavi era. This period was shaped by intense efforts to modernize Iran along European lines, particularly in relation to social and cultural reforms. As Lila Abu-Lughod has noted, by the turn of the twentieth century, debates across the Middle East, including in Iran, were already centering on women’s roles within broader discourses of national progress, anti-colonial resistance, and social transformation.19Lila Abu-Lughod, Remaking Women: Feminism and Modernity in the Middle East (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1998), 8. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, gender dynamics in Iran began to shift significantly. Women were no longer viewed merely as passive individuals, but increasingly as active participants in the project of modernization and nation-building. Their role was reimagined as they were now seen as the educators of future generations and as moral and intellectual companions to men. As a popular slogan of the time proclaimed, “women should be educated because they were educators of children, companions of men, and half of the nation.”20Afsaneh Najmabadi, Women With Mustaches and Men Without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity (California: University of California Press, 2005), 186. Afsaneh Najmabadi notes that by the early twentieth century, the argument had gained so much importance that women’s education took precedence over men’s, on the grounds that “from educated women would arise a whole educated nation.”21Afsaneh Najmabadi, “Crafting an Educated Housewife in Iran,” in Remaking Women: Feminism and Modernity in the Middle East (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1998), 102. These concerns are frequently reflected in Īrānʹdukht’s different writings, whether in her repeated appeals to Iranian mothers in Dukhtar-i tīrāh’bakht va javān-i bu’l-havas, or in an article she writes years later in memory of Day 17, 1314/January 8, 1936, where she continues to underscore the critical role of mothers in shaping the moral and intellectual fabric of society.22Īrānʹdukht Taymūrtāsh, “Bih munāsibat-i 17 Day va āzādī-i zanān” [In memory of 17 Day and the freedom of women], Āyandah 6 (Urdībihisht 1339/May 1960). In a discursive field dominated by male voices who often presumed authority over women’s issues, Īrānʹdukht’s intervention marks a significant shift by proposing an unmediated form of schooling in which a learned and educated woman like her would educate other Iranian women.

While personal and rooted in mourning her brother, this elegy belongs to this wider tradition where feminine writing works to care for and nurture a growing nation. After all, these works are written by a woman, and, as Hélène Cixous reminds us, “in women there is always more or less of the mother.”23Hélène Cixous, “The Laugh of the Medusa,” trans. Keith Cohen, and Paula Cohen, Signs 1, no. 4 (1976): 881. The maternal affect here is not necessarily a biological role accepted by women authors, as Īrānʹdukht herself never had any children from her marriage, which lasted only three years. This affect is instead a metaphor for the generative force that links a woman author to others through her use of language and the act of writing. As Emily Jeremiah observes, maternal writing “entails a publicizing of maternal experience, and it subverts the traditional notion of mother as an instinctual, purely corporeal being.”24Emily Jeremiah, “Troublesome Practices: Mothering, Literature, and Ethics” in Mother Matters: Motherhood as Discourse and Practice, ed. Andrea O’Reilly (Toronto: ARM Press, 2004), 231. In this way, maternal sentiment in literature need not belong solely to biological mothers. Rather, it can arise through acts of feminist writing that adopt care and concern for society as political and emotional gestures.

A Poet in Prose

Īrānʹdukht’s turn to prose writing, despite her evident poetic talent, reveals the profound influence of the European educational models to which she was exposed, particularly during her time at the Iran Bethel School. This American missionary-run institution combined Christian values with a reformist educational mission and shaped its students through Western pedagogical ideals by exposing them to new literary forms. While Persian literary tradition had long privileged poetry over prose, modern Persian prose emerged largely through contact with European models, especially in terms of form. Following the Constitutional Revolution of 1284–1290/1905–1911, a wave of literary reform emerged as many modernist writers challenged the artificial prose of the Qajar era. Influenced by contact with the West, these writers advocated for clarity and accessibility in literary expression and “emphasized the necessity of the use of simple Persian and indeed encouraged their contributors to write in a language that ordinary people could understand.”25Kamran Talattof, The Politics of Writing in Iran: A History of Modern Persian Literature (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2000), 21. Although Īrānʹdukht’s work often retained lyrical qualities and made references to classical Persian poetry in her writings, her decision to write novellas rather than poetry reflects the modernizing drive of her education and her desire to engage with emerging literary forms that prioritized narrative and reform over classical forms. As a woman composing in prose during the 1930s and 1940s when women’s prose in Iran was just beginning to develop, Īrānʹdukht’s writing must be seen as both shaped by and contributing to this cross-cultural literary transformation.

If modern Persian prose emerged with a tangible delay in comparison to its European counterparts, then Persian women’s prose suffered a double delay shaped by authors who were not only navigating a process of cultural acculturation but also contending with the constraints of gender. 26Anna Vanzan, “From the Royal Harem to a Post-modern Islamic Society: Some Considerations on Women Prose Writers in Iran from Qajar Times to the 1990s,” in Women, Religion and Culture in Iran, ed. by Sara Ansari and Vanessa Martin (United Kingdom: Routledge, 2002), 90. Within this context, Īrānʹdukht’s literary legacy stands out. Although she was not the only woman poet active in early twentieth-century Iran, she was the first Iranian woman to channel her poetic sensibility into prose, producing what is widely regarded as the first Iranian novel written by a woman. This shift is significant not only because prose writing by women was still uncommon, but because her novellas retain a distinctly poetic texture and sensibility that extend her lyrical voice into narrative form. Rather than marking a break from poetry, her prose reimagines it as a modern literary vehicle capable of articulating the layered and evolving experiences of women in a society undergoing rapid transformation. What makes Īrānʹdukht’s work especially notable is the way she narrates modernity through the lens of a woman living at a time when women were increasingly entrusted with the responsibility of reforming the nation. Her writing presents the fractured temporalities of this moment, starting with mourning the death of a brother and gradually propelled by a maternal, authorial voice invested in the future of the vatan. In this sense, Īrānʹdukht offers a distinctly gendered perspective on modernity, echoing Rita Felski’s provocation: “How would our understanding of modernity change if instead of taking male experience as paradigmatic, we were to look instead at texts written primarily by or about women?”27Rita Felski, The Gender of Modernity (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995), 9. Īrānʹdukht’s prose indicates that modernity in Iran cannot be comprehended exclusively through narratives of reform and progress; it can incorporate themes of grief, care, and maternal accountability. Her writing demonstrates that these emotional and social experiences are not on the edge of modernity but are a part of it. By incorporating mourning and maternal investment into the narrative of the vatan, Īrānʹdukht recontextualizes the nation’s contemporary path through the perspective of women’s lived experiences and the costs, burdens, and unacknowledged efforts they put into the modernization of their nation.

Concluding Notes

Regrettably, we do not have much written material from Īrānʹdukht Taymūrtāsh, who was known in her time as much for her poetry as her writings and speeches in periodicals. This could explain why most works that have referred to her have stopped at a biographical level merely to introduce her or highlight her family background. Despite the small amount of surviving textual evidence for Īrānʹdukht Taymūrtāsh, one should not solely gauge the importance of her literary and intellectual legacy by its volume, but rather by the depth of insight and impact it holds. While it could be argued that a brief elegy for her brother, Mihrpūr, may not fully offer a complete depiction of her thoughts and concerns as an author, contextualizing it alongside the two other novellas she authored can serve as a foundation for recognizing her influence on early twentieth-century modern Persian literature. The grief and care she wove into her poetry invite interpretation as part of the affective and ideological networks that shaped women’s authorial activism of her time. Her decision to write prose, despite her poetic sensibilities, does not make her less of a poet but instead reflects the broader literary reform she was after, like other thinkers of her time. Her poetic prose reflects her commitment to using literature as a tool for social change and education. By embracing a new form of expression, she was able to reach a wider audience and respond to the calls for change. By placing Īrānʹdukht’s maternal voice in a historical context characterized by both emotional care and political involvement in the educational reform of Iran, we can appreciate a uniquely gendered portrayal of Iranian modernity through a female lens. This perspective sheds light on the significant role women played in shaping the intellectual and moral landscape of Iran during this period. It also challenges traditional narratives that often overlook the contributions of female writers and thinkers in discussions of modernity and reform. Īrānʹdukht’s works embody precisely what Felski terms the “felt experience of being modern” from a woman’s standpoint.28Rita Felski, The Gender of Modernity (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995), 10. Through her pioneering merging of poetic voice and narrative form, Īrānʹdukht not only paved the way for Iranian women’s literary expression in prose but also positioned them as active educators of the future generation within the project of Iranian modernity. Īrānʹdukht exemplifies what it meant for a woman to write modernity rather than merely inhabit it. Her writing challenges us to expand our understanding of modern Persian literature by centering the affective labor and intellectual agency of women who were shaping, caring for, and educating the nation.

Cite this article

This paper examines Īrāndukht Taymūrtāsh’s neglected literary and cultural legacy by situating her within the gendered and pedagogical transformations of early twentieth-century Iran. Through her elegy for her brother and two novellas, it argues that Īrāndukht’s writing transforms private mourning into a maternal and didactic mode of social critique. Educated within missionary and reformist schools, she channels her poetic sensibility into prose to articulate women’s affective and intellectual participation in nation-building. Her works reimagine modernity through grief, care, and maternal accountability rather than progress alone, revealing the emotional labor through which women sustained Iran’s modernization. By merging lyrical voice and narrative form, Īrāndukht emerges as the first Iranian woman novelist and as an author whose writing renders the “felt experience of being modern” from a woman’s standpoint.