A Gadamerian Approach to Hermetic Poetry of Fīrūzah Mīzānī and Parīmāh ꜥAvānī

I am what is around me.

Women understand this.

Wallace Stevens,

“Theory” 19171Wallace Stevens, Harmonium (New York: Knopf, 1931).

Introduction

In the reading of hermetic texts, two streams emerge roughly in parallel: hermetic as a thematic aspect (what to write), or as a linguistic concern (how to write). Thematically, hermetic texts, both in content and naturally in form, obediently follow the examples of ancient hermetic texts, such as Corpus Hermeticum, attributed to Egyptian Hermes (philosopher, prophet, sage) or Hermes Trismegistus (thrice-great).2Hermes Trismegistus, The Corpus Hermeticum: Sacred World (n.p.: The Big Nest, 2016). Hermetic texts, or Hermetica, are enriched with hermetic teachings in the fields of alchemy, astronomy, magic, mysticism, philosophy, wisdom, theosophy, and secret societies such as Kabbalism, Shamanism, and Freemasonry.3Jennifer N. Wunder, Keats, Hermeticism, and the Secret Societies (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008), 48; Glenn Alexander Magee, Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001). Therefore, it is not surprising that we come across Hermetic philosophy, Hermetic physics, Hermetic medicine, and naturally, Hermetic literature.

Previous studies have sought to understand the relationship between the poetry and the hermetic thoughts of writers such as W. B. Yeats,4Paula Moschini Izquierdo, “An Image of Mysterious Wisdom”: Hermetic Philosophy and Dual Selfhood in Yeats’s Poetic Dialogues” (Bachelor’s thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 2018). Henry Vaughan,5Wilson O. Clough, “Henry Vaughan and the Hermetic Philosophy,” Publications of the Modern Language Association 48, no. 4 (1933): 1108–30. Andrew Marvell,6Maren‐Sofie Røstvig, “Andrew Marvell’s ‘The Garden’: A Hermetic Poem,” English Studies 40, no. 1 (1959): 65–76. Katherine Philips,7Sajed Chowdhury, “Hermeticism in the Poetry of Katherine Philips,” Katherine Philips: Form, Reception, and Literary Contexts 23, no. 4 (2019): 45–62. and John Keats.8Wunder, Keats, Hermeticism, and the Secret Societies. Anglo-Saxon literary tradition presented a challenge for the incorporation of hermetic terminology and doctrine into English poetry. For instance, concepts of the unity of being and self-wisdom in W. B. Yeats’s poetry were deep in conversation with hermetic tradition.9Izquierdo, “An Image of Mysterious Wisdom.”

The seeds of the linguistic concern of hermetic poetry were sown in France, and the hermetic deals with symbolism.10Silvie Špánková. “Rui Knopfli, a Nomad between Sion and Babylon,” in Centers and Peripheries in Romance Language Literatures in the Americas and Africa, edited by Petr Kyloušek. 1st ed. (Boston: BRILL, 2024), 528–45. For example, Stéphane Mallarmé, a quasi-Hermetist poet, emphasized alchemy in language, and his pure poetry (Poésie pure) sought to invent a mysterious and sacred language,11Petra Leutner, Wege Durch Die Zeichen-Zone: Stéphane Mallarmé Und Paul Celan (Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2016). which Paul Valéry described as “The problem of Mallarmé.”12Paul Valéry, The Collected Works of Paul Valéry: Leonardo, Poe, Mallarmé, translated by Malcolm Cowley and James R. Lawler, edited by Jackson Mathews (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 8: 258. The meaning of this problem Valéry’s description comes out “with rhythms of fragmentation and silence; dislocated syntax; the rapid formation, transmutation, and evaporation of images; and thoughts that seem to escape being fixed into any one interpretation.”13Elizabeth McCombie, “Introduction,” translated by E. H. Blackmore and A. M. Blackmore, in Stéphane Mallarmé: Collected Poems and Other Verse (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), ix.

In the 1930s, Italian hermetic poetry as a literary movement, whose practitioners included Giuseppe Ungaretti, Salvatore Quasimodo,14Later, Salvatore Quasimodo left the movement and turned to realism. See John Picchione and Lawrence R. Smith, Twentieth-Century Italian Poetry: An Anthology (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 12. Eugenio Montale, Alfonso Gatti, and later Mario Luzzi (as classified by Francesco Flora), under the influence of French symbolism, emerged from a concern for fascism.15Virginio Orsini, “An Introduction to Hermetic Poetry,” East and West 2, no. 2 (1951): 109–11; Yi Chen, “Semiosis of Translation in Wang Wei’s and Paul Celan’s Hermetic Poetry,” Cultura 9, no. 2 (2012): 87–102. They made efforts to emphasize the sound of words and also sincerely believed that “language was pure intuition, made up of sudden illuminations and revelations of spirit and truth.”16Picchione and Smith. Twentieth-Century Italian Poetry, 12.

In German, the distinctive linguistic characteristics of hermetic poetry (i.e., obscurity, ambiguity, difficulty) reached their peak in the works of poets such as Rainer Maria Rilke,17Susan McCabe, “The “Spiritual Realism” of Rainer Maria Rilke and H.D.,” Ex-centric Narratives: Journal of Anglophone Literature, Culture and Media 7 (2023): 93–105. Georg Trakel,18Richard Millington, The Gentle Apocalypse: Truth and Meaning in the Poetry of Georg Trakl. Vol. 209. (New York: Camden House, 2019); Karsten Harries, “Language and Silence: Heidegger’s Dialogue with Georg Trakl,” Boundary 2 (1976): 495–511. and Paul Celan.19Hans-Georg Gadamer, Wer Bin Ich Und Wer Bist Du?: Ein Kommentar Zu Paul Celans Gedichtfolge “Atemkristall” (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1989). In Who Am I and Who Are You? (Wer bin Ich und wer bist du?), Hans-Georg Gadamer regarded the message of Celan’s poetry as unacceptable and he admitted that we are rarely on Celan’s side because of his encrypted lyrics.20Gadamer, Wer Bin Ich Und Wer Bist Du?, 156.

The use of hermetic techniques in poetry is also seen in the United States with Wallace Stevens,21Robert Bly, “American Poetry: On the Way to the Hermetic,” Books Abroad 46, no. 1 (1972): 17–24. Hilda Doolittle,22Jason M. Coats, “H. D. and the Hermetic Impulse,” South Atlantic Review 77, no. 1/2 (2012): 79–98. and John Ashbery;23John Ashbery, Other Traditions (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001); Kimberly Quiogue Andrews, The Academic Avant-Garde: Poetry and the American University (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023). in Hungary with Mihály Babits and Sándor Weöres;24András Sándor, “The Schizophrenia of Poets: Hermeticism in Hungary,” Books Abroad 46, no. 1 (1972): 31–36. in Spain with Juan Ramon Jimenez;25Michael P. Predmore, “The Structure of the “Diario De Un Poeta Reciéncasado”: A Study of Hermetic Poetry,” Contemporary Literature 13, no. 1 (1972): 53–105. and in Israel with Avot Yeshurun.26Michael Gluzman, “Avot Yeshurun’s Self-Commentary,” Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 21, no. 1 (2022): 99–121. Hermetic poetry is perhaps best defined in the words of Robert Bly: “Hermetic poetry is not something like gold, which either is gold or not, but something like oceans, which exist at all depths.”27Bly, “American Poetry,” 17. Hermetic poets actively encourage the language to develop in depth. Therefore, the difficulty of their poetry is not necessarily patently artificial, but comes from the careful crafting of the poems. Reading hermetic poetry may be demanding or challenging because of its self-referential, veiled, or deliberately concealed nature and might give inconsistent readings. But hermetic poems do not create a private language in which incomprehensible or non-understandable verses take shape; they demand their own readers.

Figure 1- Book covers of poetry by Fīrūzah Mīzānī (two on the left) and Parīmāh ꜥAvānī (two on the right) in Persian.

Hermeneutics as Understanding

Hermeneutics is largely preoccupied with hermetic literature.28Peter Szondi, Introduction to Literary Hermeneutics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 25. Since our understanding of hermetic poetry might be subject to possible problems, how the reader or interpreter deals with the text is crucial. Hans-Georg Gadamer, who claimed that “there is no longer a hermeneutical method” (Eine hermeneutische Methode gibt es nicht),29Gadamer, Wer Bin Ich Und Wer Bist Du?, 150. believed that our experience and knowledge are bounded by time and history; therefore, discovering the truth of a text does not lie exclusively with the disposal of the method. According to Gadamer, it is true that hermeneutics is able to make explicit what is implicit,30Hans-Georg Gadamer, Beginning of Philosophy, translated by Rod Coltman (London, New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc, 2001), 102. but we should concentrate upon carrying it out through understanding by direct dialoguing with the text, like a game (Spiel), which should be taken seriously and must be respected in accordance with its rules.31Hans-Georg Gadamer, Gesammelte Werke: Hermeneutik I. Wahrheit und Methode: Grundzüge Einer Philosophischen Hermeneutik (Tübingen: Mohr, 1999), 1:107. Thus, hermeneutics, instead of ars interpretandi (the art of interpretation in search of meanings of texts), would become an art of understanding.

Gadamer, whose theoretical framework provides the basis for this study, defines the understanding of the text linguistically. Understanding is a linguistic event (Geschehen), and naturally what is understood is spoken. According to Gadamer, “everything that exists is reflected in the mirror of language” (im Spiegel der Sprache reflektiert sich vielmehr alles, was ist).32Hans-Georg Gadamer, Gesammelte Werke: Hermeneutik II. Wahrheit und Methode: Ergänzungen. Register (Tübingen: Mohr, 1993), 2:242. Our understanding of the world is linguistic and is bound actually to happen within the language; therefore, we can not understand anything outside of language. In other words, “the being which can be understood is language”33Translated by Jean Grondin. (Sein, das verstanden werden kann, ist Sprache).34Gadamer, Gesammelte Werke, 1:478. In this sentence, the main emphasis is on the word “can.”35Jean Grondin, Introduction to Philosophical Hermeneutics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), 120. Here, the “understanding is itself insertion into being.”36Jean Grondin, The Philosophy of Gadamer, translated by Kathryn Plant (Stocksfield: Acumen Publishing Limited, 2003), 151. Thus, efforts of readers of a text to grasp its meaning and reach understanding are largely focused on their ability to face the text. As a result, our understanding is historical and linguistic and is formed by relying on tradition and time, and can not exist in a vacuum. Naturally, the reader of poetry is not, and could not be, a blank slate.

Method and methodological tools are not necessarily the only means to grasp the hidden meaning of poetry. Of course, we should add this basic point that, based on the Gadamerian assumption, there is fundamentally no definitive and predetermined meaning in poetry and we are only supposed to provide the conditions of possibility for understanding via our prejudices,37Inga Römer, “Method,” in The Blackwell Companion to Hermeneutics, edited by Niall Keane and Chris Lawn, 86–95 (Chichester, West Sussex; Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons, 2016), 90. not presently understanding itself. To understand, the reader needs to enter into a close dialogue with the text. The text allows us to ask questions because the dialectical (dialogical) element is featured prominently. The text allows us to ask our questions from inside because the dialectical relationship between the reader and the text creates contexts for realizing meaning. There is absolutely no point in searching for the text’s meaning outside the coherence, especially for hermetic poems; namely, there is no more reliable source to answer the questions of the poem than itself. Gadamer, who published the outcome of his dialogues with Celan’s hermetic poems in “Who Am I and Who Are You,” teaches us how we could lead to a state of understanding on a coherent level. Gadamer explains that understanding is a linguistic event that occurs when our horizons (i.e., history, tradition, experience, prejudice) and the text mix together, and the meaning of the text coincides with the text exactly during the dialogue, in the melting with the reader’s horizons. On this basis, understanding is mentioned in connection with an event, not with a seemingly spontaneous thing. This is where “we do not understand better [as Schleiermacher strongly emphasizes],38“Man muß so gut verstehen und besser verstehen als der Schriftsteller” [bracketed addition is mine]. See Friedrich Schleiermacher, Kritische Gesamtausgabe: II. Abt. Band 4., herausgegeben von Wolfgang Virmond (Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 2012), 39. but only differently.”39Grondin, Introduction to Philosophical Hermeneutics, 140.

What kind of poetry has felt the need for hermeneutics? The real poet allows “Thou” to speak independently, and in their poetry, none of the parties of the dialogue can be assumed to be an object (Gegenstand). In such poems, both [= I and Thou] are subjects. It is not possible to meet “Thou” without “I”. A poem is able to show its interpretive value to the reader when “Thou” in the poem is an independent person like “I”; as Gadamer says: “A Thou is not an object, but relates to someone” (Ein Du ist nicht Gegenstand, sondern verhält sich zu einem).40Gadamer, Gesammelte Werke, 1:364. The reader can find out who “I” is and who “Thou” is by closely following the behaviours and actions attributed to them.

The I-Thou dialogue-driven poetry could be open to the right interpretation, but interpretation should not be kept widely separate from poetry. Gadamer’s idea of interpretation originated with his profound thoughts about new experience: “The interpretation is correct if it finally fades completely because it has completely entered into the new experience of the poem” (eine Interpretation ist nur dann richtig, wenn sie am Ende ganz zu verschwinden vermag, weil sie ganz in neue Erfahrung des Gedichts eingegangen ist).41Gadamer, Wer bin Ich und wer bist du?, 156. The translation is mine. Therefore, there is no doubt that the interpretation here has evoked a new type of art: understanding.

In order to create a degree of internal coherence in the poetry, one must be able to enter through the hermeneutic cycle. The hermeneutic cycle means “we can only gain this understanding of the whole by its parts,”42Jean Grondin, “The Hermeneutical Circle,” in The Blackwell Companion to Hermeneutics, edited by Niall Keane and Chris Lawn, 299–305 (Chichester, West Sussex; Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons, 2016), 299. and it arises from our deep-rooted prejudices, but our prejudices might be false. From a Gadamerian perspective, our false prejudices can replace true ones in the temporal distance (Zeitenabstand).

Hermetic Poetry in Iran

The roots of hermeticism in pre-Islamic Iran can be traced back to Middle Persian in the Sasanian Empire (2nd–6th centuries), which is likely to have been influenced by original Greek texts; and a further hermetic oeuvre entered Arabic via translation from Middle Persian.43Kevin Van Bladel, The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 27–28. With the Islamization of Iran in the seventh and eighth centuries, hermeticism deeply penetrated into the Iranian-Islamic philosophy and Sufism. Henry Corbin asserts in The History of Islamic Philosophy that Hermes “was one of the five great prophets who preceded Mani. The figure of Hermes passed from Manichaean prophetology into Islamic prophetology, in which he is identified with Idris and Enoch (Ukhnukh).”44Henry Corbin, History of Islamic Philosophy, translated by Liadain Sherrard (London: Kegan Paul International and The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 1993), 125. He further points out that hermeticism in Islam was doctrinally accepted by the Shiite attitude that was influenced by hermetic thinking, especially in terms of “The ascent of the spirit to heaven.”45Corbin, History of Islamic Philosophy, 125.

Hermetic alchemy in Iranian Islam was developed from Jābir ibn Hayyān’s oeuvre (Jabirian corpus) in the eighth century. One of the fundamental concepts formulated in Jābir’s alchemy is the “science of the Balance,” in which the manifest and the hidden in an alchemical operation are considered as a spiritual exegesis.46Corbin, History of Islamic Philosophy, 130. The balance is neither a quantitative system nor a measuring of objects, but it is a search for the body’s soul. In so doing, the soul places the transmutation of bodies in the world. It is worth noting that the letters of the alphabet, for bearing a divine Name, produce the most complete balance, according to the Jabirian intellectual apparatus.47Corbin, History of Islamic Philosophy, 131.

Afterward, Hermes’ doctrine exerted an overwhelming influence on Shihāb al-Dīn Suhravardī (known as Shaykh al-ishrāq) in wisdom, alchemy, and especially illuminations in the twelfth century. Following Hermes, Plato (particularly the cave allegory48Tianyi Zhang, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Nature of Suhrawardī’s Illuminationism: Light in the Cave, vol. 17. (Leiden: Brill, 2023).), and Zarathustra, he sought to revive the spiritual vision of ancient Persia. In Oriental Theosophy (Hikmat al-ishrāq), Al-Suhravardī begins to explore Hermes as the “Father of all Sages.”49Corbin, History of Islamic Philosophy, 186. Corbin defines the adjective ishrāq, or the light, as “auroral, an oriental light, that what the morning splendor reveals, the Rising Star,” which symbolically represents an Iranian spirituality.50Corbin, History of Islamic Philosophy, 9.

Both Oriental Theosophy and Science of the Balance, aside from their spiritual contents, present wisdom or divine knowledge in a cryptic and symbolic language. Al-Suhravardī explains that “the code (ramz) is undeniable” (falā raddu ꜥalā al-ramza) and therefore “the ancestors’ language was cryptic” (wa kalimātu al-avvalīna marmūzahu).51Hassan Siyid ꜥArab, Tashīh, tꜥarīb, tarjumah va sharh-i muqaddamah-yi Hikmat al-ishrāq [A correction, adaptation, translation and commentary on the introduction of the Oriental Theosophy] (Tehran: Hirmis, 1399/2020), 58. In other words, the truth should be fully expressed in an encoded language. This is a type of Iranian meditation to prevent strangers from accessing the truth. Shams al-Dīn Shahrazūrī, one of the most important Oriental Theosophy interpreters, provides three justifications for using encoded language: 1. “If a stranger finds out about it, it will cause evil and corruption; 2. The mysterious word prompts the reader to try to understand and discover it; and 3. Understanding the code enlightens the mind and strengthens the soul to think.”52Siyid ꜥArab, Tashīh, tꜥarīb, tarjumah va sharh-i muqaddamah-yi Hikmat al-ishrāq, 70. Simultaneously, in Sufism, secrets should not be revealed and disclosure of such secretes was considered a major crime. The best-known such example is Mansūr al-Hallāj (3rd–4th centuries AH/9th–10th centuries), who was martyred for saying “I am the Truth” (anā al-Haqq)53It should be noted that “the Truth” is one of the names of God in Islamic philosophy. and revealing the secret. Hāfiz-e Shīrāzī (8th century AH/14th century), the most famous hermetic Iranian classic poet, describes this event in his sonnet (ghazal): “That darling, who became high his head on the hanging / His crime was that he revealed secrets.”54The translation is mine.

One of the earliest Iranian poets to use mystical and symbolic language in his work was Hakīm Sanāʾī Ghaznavī in the 6th century AH/12th century;55Nasrʹallāh Pūrjavādī, Shiꜥr va sharꜥ: Bahsī darbārah-yi filsifah-yi shiꜥr az nazar-i ꜥAttār [Poetry and piety: A discussion on the philosophy of poetry from ꜥAttār’s point of view] (Tehran: Asātir, 1374/1995), 101. later poets to continue this practice included ʿAttār of Nishāpūr (12th–13th centuries) and Jalāl al-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī (13th century), and finally, Hāfiz. These classic poets, however, are not hermetists. The difficulty of reading Iranian classic poems stems from their authors’ tendencies to speak in secret and hide the poems’ meaning, which is firmly rooted in Sufism. Therefore, with the exception of Hāfiz, who was a poet with mystical tendencies, these authors were mystics or sages in the clothes of poets.

The Hermetic in Modern Persian Poetry

As noted previously, the new definition of hermetic poetry deals with the challenges it presents to reading, the obscurity of its vocabulary, and the delays in reader understanding, perhaps due to its use of strange syntax or latent complexity. Moreover, the difficulty could lie in its “hidden harmony/attunement,” as Heraclitus said,56Charles H. Kahn, The Art and Thought of Heraclitus: An Edition of the Fragments with Translation and Commentary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 65. which, when compared to conventional grammar, presents new rules that readers may find unfamiliar. Even though hermetic poetry in Iran is not considered a well-organized literary movement, modern Persian poetry has retained elements of hermetic characteristics in its language and has given itself a new orientation through familiarity with the main literary streams in France, such as symbolism and surrealism. Alongside the background of mystical literature (i.e., Sufism) and linguistic innovations in modern Persian poetry such as blank verse arising from the theory of Nīmā Yushīj, these characteristics can be found in shiꜥr-i mawj-i naw by Ahmadʹrizā Ahmadī, shiꜥr-i dīgar by Bījan Ilāhī, shiꜥr-i hajm (Spacemantalism) by Yadallāh Ruyāʾī, and shiꜥr-i mawj-i nāb poets in new styles.57I have previously discussed the works of twenty hermetic Iranian poets in the century between 1921 and 2021. See Maziar Chabok, Rukhdād-i fahm (Sharhī bar kārʹnāmah-yi shāꜥirān-i hirmisī-yi muꜥāsir-i Īrān) [Happening of understanding: A commentary on contemporary Iranian hermetic poets] (Tehran: Siyāhrūd, 1401/2023). All of these modern styles of Persian poetry have found themselves on common ground with regard to the question of poetic language.

Shiꜥr-i mawj-i naw, which appeared with the publication of Ahmadī’s book Tarh (Design) (November, 1340/1962), kept poetry extremely close to the concrete-pictorial and imagistic nature of prose; for instance, “The silence revolved like a little whirligig” (sukūt chūn firfirah-yi kuchak mī-charkhad).58Ahmadʹrizā Ahmadī, Tarh [Design] (Tehran: n.p., 1340/1962). Ahmadī completely abandoned the weight of prosody and the matter-of-fact expression in favour of pure poetry (Poésie pure). But unlike the French tradition of Poésie pure, shiꜥr-i mawj-i naw were fairly simple poems that were aesthetically, and especially in terms of reality definition, based more on surrealism.

Two serious and effective poetic streams, called shiꜥr-i dīgar and shiꜥr-i hajm, branched off from shiꜥr-i mawj-i naw.59Ismāꜥīl Nūrī ꜥAlā, Suvar va asbāb dar shiꜥr-i imrūz Īrān [Pictures and reasons in today’s Iranian poetry] (Tehran: Bāmdād, 1348/1969), 320. Both of these emerged in the late 1340s/1960s and sought to escape from the central and dominant discourse in Iran of popular and committed literature.

The name shiꜥr-i dīgar is taken from a magazine, “Juzvah-yi shiꜥr,” published in 1344/1966, which featured the works of poets such as Bījan Ilāhī, Parvīz Islāmpūr, Bahrām Ardabīlī, and Muhammad Rizā Aslānī. Later, most of them joined the shiꜥr-i hajm movement, which emerged in 1347/1969 with the publication of a manifesto of “language madness.” Yadallāh Ruyāʾī defined the poem as a subjective fragment and believed that shiꜥr-i hajm “commits before committing.”60Yadallāh Ruyāʾī, Halāk-i ꜥaql bih vaqt-i andīshīdan [The doom of reason in the time of thinking] (Tehran: Nigāh, 1391/2012), 37. Therefore, poets should reflect on their poetry and progress from reality to meta-reality. Complex syntax, wise tone, concise writing, long-winded expressions, archaic words, and strange associations are among the characteristics of shiꜥr-i dīgar and shiꜥr-i hajm, as seen in the following examples: “on the height of the wound / I had a flight” (bar irtifāꜥ-i zakhm / parvāz dāshtam) (Ruyāʾī), “all day sky / with a beautiful poverty like a palm of hand / has crowned me” (hamah-yi āsmān-i rūz / bā faqrī zībā chun yek kaf-i dast / marā tājʹguzārī kardahʹst) (Ilāhī), “Leprosy can make the breath of the sky a virgin” (juzām mī-tavānad tanaffus-i āsmān rā bākirah kunad) (Islāmpūr), and “I am blowing / on the sea / between two winds / between two leaves / on the sea” (man rūy-i daryā / miyān-i du bād / miyān-i du barg / man rūy-i daryā / vazānam) (Aslānī).

The period between 1352–1354/1974–1976 in Tamāshā magazine, under the editorship of Manūchihr Ātashī, saw poets such as Siyid ꜥAlī Sālihī, Hurmuz ꜥAlīpūr, Āriā Āriāpūr, Yārʹmuhammad ꜥAsadpūr and Sīrūs Rādmanish, who became known as mawj-i nāb. Working from the previous contributions of avant-garde literary movements in Iran, they added complex concepts, compression, and local, rural-natural elements to their poetry; in this respect, they brought their poetry closer to pastoral poetry. They were also looking for a “pure reader.” Many of their works feature examples of abstract pastoral imagery such as “A happy petal in the water” (gulbargī shād dar āb) (Rādmanish) or “the fall of crying on the wings of the heart / tears my old voice” (furūd-i giryah bar bālʹhā-yi dil / sidā-yi qadīm-i marā pārah mī-kunad) (Āriāpūr).

The hermetic expression as a linguistic concern is prominent in most modern Persian poetry movements. Although this expression was very common in the movements before the 19357/1979 revolution, serious and eloquent poets who have passed through these streams are working in Iran in the new millennium as well, and the influences of the previous movements can be seen in their poetry.

Fīrūzah Mīzānī can, and should, be included in this discussion as the only female poet in shiꜥr-i mawj-i nāb, not only because she is a contemporary of that period (1352–1354/1974–1976), but also because of the elements, such as pastorality, that her poems share with others of that movement. Even though Parīmāh Avānī is an independent poet of the new generation of modern Persian poetry, many features of shiꜥr-i dīgar and shiꜥr-i hajm, such as surrealistic images, can be seen in her work. Therefore, this study focuses on Mīzānī and Avānī as hermetic poets before and after the 1357/1979 revolution in Iran to show that hermetic poetry is still alive in Iran and that these authors’ works are representative of the main currents of Persian hermetic poetry.

Fīrūzah Mīzānī

Fīrūzah Mīzānī can be considered one of the first contemporary female hermetic poets in Iran.61Batūl ꜥAzīzpūr (1332/1953–) should be acknowledged here as well. She was born in 1329/1950 in Tehran and has been known as a poet since 1353/1975 thanks to her literary activities in magazines. She has published two books of poetry: Tarāvat-i āvārah dar digardīsī (Wandering freshness in transformation)62Fīrūzah Mīzānī, Tarāvat-i āvārah dar digardīsī [Wandering freshness in transformation] ([Tehran]: Bāmdād, 1357/1979). in 1357/1979 and Hasūdī bih sang (Envious of the stone)63Fīrūzah Mīzānī, Hasūdī bih sang [Envious of the stone] (Tehran: Buzurgʹmihr, 1374/1994). in 1374/1994. She was also the editor of Shiꜥr bih daqīqah-yi aknūn (Poetry of the moment)64Fīrūzah Mīzānī and Ahmad Muhīt, Shiꜥr bih daqīqah-yi aknūn [Poetry of the moment], vol. 3. (Tehran: Nughrah, 1376/1996). in three volumes (released between 1368/1988 and 1376/1996), a comprehensive collection of four decades of modern Persian poetry.

Mīzānī’s poetry is marked by its omission of verbs, syntactic changes, and emphasis on the musicality of the text. By framing questions in the text, she diverts the normal flow of narrative onto a new course, and this technique forms a noticeable feature of her poetry. In addition, Mīzānī’s interest in personalization can be seen in examples such as “the scapula of the mountain” (kitf-i kūh), “sleep / has gone to fetch water from the springs” (raftah āb biyāvarad az chashmahʹhā khvāb), “arms of the star” (bāzūvān-i sitārah), “this moon heard me” (īn māh marā shinīd), or “the bell / has come down from the tower / to play the time” (zang / az burj pāyīn āmadah / vaqt rā binavāzad).65These verses were selected from Hasūdī bih sang.

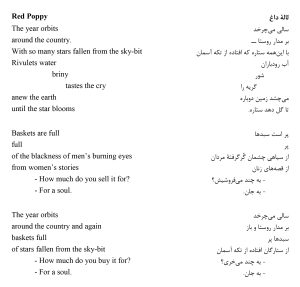

One such poem in the Hasūdī bih sang collection with these features is “Red Poppy”:

The poem begins with a description of the passage of a year in the country, at a certain time in a certain place, characterized by rivers that taste the passion of crying, and stars fallen from a bit of sky that produce flowers; specifically, blood-red poppies, can be a reflecting the sad state of the people described in the poem. The basket that should be full of fragrant and happy flowers is “full of the blackness of men’s burning eyes from women’s stories”; it is full of the red poppy, full of evil flowers. In Iranian culture, and aligned with the Canadian poet John McCrae, the red poppy is a supreme symbol of martyrdom, and Iranians liken the red color of the poppy to the grieving in the mourners’ hearts. According to the poem, this basket full of suffering was not given to us for free, but is paid by the “soul.”66This article, based on Gadamer’s recommendation, focuses specifically on the soul of this poem and does not consider the historical or mythical soul . This basket is our history, full of the blackness of men’s eyes, of the events with which the earth fertilizes even the rejected stars, as a result of which red poppies start to grow, and the cycle repeats throughout history.

Although neither “I” nor “Thou” are used explicitly, we feel close to this poem. The country described in the poem is a microcosm of our entire world; a world with rural characteristics, a space containing less awareness and more suffering. The regular rotation of this event in the circuit, and the repetition of such buying and selling, of life and death, continues. What could change the course of our dark history is time, but what kind of time, the poem does not say. Naturally, this is not an ordinary time, but a time when the accumulation of experiences gives us pause to reflect on ourselves. Elapsed time should lead to growing awareness, but the cost of knowing about historical events may not be less than dying in history itself.

The poem’s particular emphasis is upon the historical being whose consciousness is affected by history and at the same time is aware of their influence (Wirkungsgeschichte, effective history, based on Gadamer’s viewpoint). The poem bluntly warns its readers that in order to change this terrible cycle of repetitive dark history, we should not only be under the enormous influence of history, but also allow the passage of time to provide us with the opportunity to become aware and significantly affect the cycle; Otherwise, we will buy a basket full of darkness that comes from the past, only “for a soul” and if we are not aware, it will sell the same bloody basket for twice the price of the soul, the basket that was lost for the existence of those two souls.

Parīmāh ꜥAvānī

Parīmāh ꜥAvānī, who was born in 1367/1988 and grew up in Tehran, has published three books of poetry: Parsahʹhā-yi mutilāshī (Decomposed rambling)67Parīmāh ꜥAvānī, Parsahʹhā-yi mutilāshī [Decomposed rambling] (Tehran: Tapish-i Naw, 1389/2010). in 1389/2010, Tughyān-i dūr (Remote Revolt)68Parīmāh ꜥAvānī, Tughyān-i dūr[Remote revolt] (Tehran: Gūshah, 1392/2012). in 1392/2012, and Jādūʹnāmah-yi Āntālūs: Girdāvarīʹhā-yi Nikārchīl Ūrūsā (The Magic Scroll Verses of Antalus: Compiled by Nikārchīl Ūrūsā)69Parīmāh ꜥAvānī, Jādūʹnāmah-yi Āntālūs: Girdāvarīʹhā-yi Nikārchīl Ūrūsā [The magic scroll verses of Antalus] (Tehran: Afrāz, 1399/2020). in 1399/2020. She is an Iranian-born author with strong credentials in art, holding a PhD in History of Contemporary Art from Sapienza University, and is very familiar with the language and imagery of colour. Her figurative paintings featuring mythological themes and symbols have been displayed in many Italian and German galleries.

The asymmetry of the narrative, the unpredictability of the text, and the free imagination of her poetry bring ꜥAvānī closer to the surrealists. For example, she does not describe the taste of the other’s body as sweet or bitter, but as “Your flavor was the monarchy of delusion,”70ꜥAvānī, Parsahʹhā-yi mutilāshī, 46. to move the mind beyond tastes and colours.

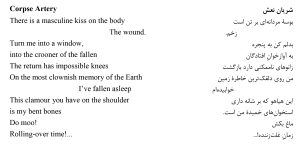

Similar imagery occurs in Sharyān-i naꜥsh (Corpse Artery), included in the Parsahʹhā-yi mutilāshī collection:

The “rolling-over time” and “the most clownish memory of the Earth” are in connection with two complementary elements of this poem: time and death, or repetition and transformation. The imagery suggests a circus show in which Death, riding on the cow of time, has bones on display belonging to people who have been turned into windows. The first stanza describes “a masculine kiss” that bruises, wounds, and finally throws the speaker out of the window, and places it haphazardly on the shoulders of death. At this moment, the cow of time moos and calls for a return to time that is not only backward but rolling to and fro, that turns us into something unexpected. Why is death directly attributed to a masculine kiss? Who has dropped this wounding kiss of death on the body? A masculine kiss is not strictly limited to sexuality; it is a kiss that wounds and kills.

The mooing of time marks a rare event: despite being “bent over,” the bones do not stop clamouring. The clamour is one of the crucial elements in living and protecting the speaker from death, like the excitement of love that is always with us and will be until the end, as long as masculine kisses are physically capable of wounding and destroying the body. Time, here described as “impossible knees,” cannot return. The clamouring bones of the speaker, who rests on the shoulder of “the most clownish memory of the earth,” see their fate in the hands of death, which transforms us into something at every turn of time. The speaker wants time to turn him into a “window” and “the crooner of the fallen.” We should remember that the speaker converses with time in the forms of the imperative “Do moo” and an addressive “Rolling-over time!” That is, the speaker determines what he wants from time and when it raises its voice. Therefore, the speaker has in mind the scene of death, whose repetition seems to depend on time, to repeat the memory of falling from the window. The “Fallen” intends to return, but no generous return has been made.

It is death that takes our boisterous bones on its shoulder and happily rollicks with a newly fallen person. Here earth and time provide death with a platform to play with our bones and transform them into new shapes.

ꜥAvānī’s paintings, like her poetry, use the imagery of the fallen, as seen in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Martian Liberty March, Acrylic and Persian ink on Canson paper, 30 x 40, 2022, Turin, Italy Source: https://parimahavani.com/works/

Neither the time of this poem nor real time is reversible, but they become essentially separate at a point. The speaker demands the return of the event, and irreversible time turns him into a non-human object or being in return: a surreal act that demonstrates a radical change in the nature of “I” in time. The climax of the poem is that the speaker calls for a change in the human being, as though committing the fallen to memory bothers him. In becoming an object, the speaker intends to be merely an unimpeachable witness to the other fallen, not becoming a human who is re-wounded by every masculine kiss and brings back the painful memory of the return. The speaker eludes human memory and, despite his desire to return, wants to appear in the form of a window and a crooner. As a result, death, as “the most clownish memory-maker on earth,” presses his masculine kisses on the body. Death is described here as a “clownish memory-maker” because it returns the body to the earth, and time transforms us again at every turn. Therefore, death only happens to “I”. For this reason, “I” is willing to turn into a thing that does not have death, that it does not exist and can not remember anything in its transformation, like the time that conveniently keeps forgetting when it has to moo and as if it is “I” that wakes it up for rolling over and mooing. Thus, “I” is looking for a memoryless thing that can sit on the shoulders of the cow of time to recover his clamour and moo for the newcomers who are fallen from the window of life.

However, some questions remain unanswered in this poem. Is the memory of living and tasting the wounding kiss so painful that we prefer to turn into memoryless objects in returning to life? Are memories like hard and firm kisses that are imprinted on our bodies, and are they the cause of our death? After death, what will not be absolutely separated from our bones is the clamour, which will not be extinguished even in progressive time. It is the clamour that makes memories and turns every memory into a kiss, and in turn, in the end, the last kiss we receive will come from the most clownish creature on earth. If the speaker is a memory-maker and boisterous person who receives a masculine kiss and dies, should we wait for an effeminate kiss to destroy objects?

Conclusion

This study is a cautious approach to two hermetic poems that implements the practical aspect of Gadamer’s hermeneutics. It is also influenced by Schleiermacher’s notion that misunderstanding and non-understanding move shoulder to shoulder in the process of understanding. Hermetic poetry shows us that we can at least grasp the barrier between us by listening carefully to the inner voices of words.

Both poems embody a wealth of experience about time. Mīzānī’s presentation of time demonstrates that progress must be accompanied by awareness, and ꜥAvānī’s depiction of time reminds readers that the return of time can be wounding and painful.

These interpretations are unwilling to make definitive claims about the latent and subtle meaning of the poems. These are the experiences of the reader who strives to hear every moment. The essential point of this article is that the level of hermeticity of a text depends greatly on the context of the language. Each linguistic tradition has its own constraints and opportunities. Iranian poets can use the historical hermetic characteristics of Farsi to enhance their linguistic capability and bring it forward for modern readers; they also make use of the same precious gem sought the world over: the true word.