Laylā Mahbūbī: A Feminist Pastoral

To Vahīd Amīnīzādah Yazdī and their Zhīvār

Introduction

Pastoral poetry emerged from the contradiction between the urban and the rural, fueled by the duality of culture and nature, complexity and simplicity, the real and the ideal, repulsion and attraction.1Sarah Phillips Casteel, “New World Pastoral,” Interventions 5 no.1 (2003): 12–28. doi:10.1080/13698032000049770. Pastoralism played a vital role in countering urbanization,2David M Halperin, Before Pastoral: Theocritus and the Ancient Tradition of Bucolic Poetry (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), 56. and this fundamental aspect of the pastoral extended beyond neutral, nature-describing poems about flowers, shepherds, and waterfalls. In this way, pastoral poetry addresses issues raised by urban development by either constructing a new, imagined place or nostalgically encouraging to retreat to the old one.

Laylā Mahbūbī, a contemporary Persian poet, brings new perspectives to pastoral poetry—not by creating a utopia, as is common in classical pastoral poetry, nor by a regretful sanctification of the past. Drawing on original experiences and feminist concepts shaped by her family’s migration from Azerbaijan to Iran, Mahbūbī has expanded the scope of pastoral poetry in Iran. She stands out due to her unique interpretations of land, women, and nature as feminist pastoral themes. Her poetry offers an unprecedented reflection on the historical condition of a woman’s body—one that has lost its land and is continually harmed by natural forces. The fate of humanism, in her work, can neither progress nor retreat. This contradiction intensifies when women, depicted as the defeated protagonists of her poems, recall their identities destroyed by modern developments such as technology and war.

This study seeks to uncover three themes in Laylā Mahbūbī’s works as a feminist pastoral poet in two poetry collections published in Iran: Bih zakhm′hā-yam surmah mī′kishad zanī (A woman is tinging my wounds with kohl)3Laylā Mahbūbī, Bih zakhm’hā-yam surmah mī′kishad zanī (Tehran: Dāstān, 1396/2017), 5. and Bī huzūr-i ghubār-i dast (In the absence of the hand’s dust).4Laylā Mahbūbī, Bī huzūr-i ghubār-i dast (Tehran: Dāstān, 1397/2018). Before delving into the depth of Laylā Mahbūbī’s poetry, I also trace the trajectory of pastoral poetry in the West and Iran to establish Mahbūbī’s position and highlight her contributions to this genre.

Figure 1

Left: Cover of Laylā Mahbūbī’s book, Bī huzūr-i ghubār-i dast.

Right: Cover of Laylā Mahbūbī’s book, Bih zakhm’hā-yam surmah mī′kishad zanī.

A Glimpse into the Concept of Pastoral Poetry

To explore the roots of pastoral poetry, we must trace them back to the Greek poet Theocritus of Syracuse (ca. 300–260 BCE), who, in the Hellenistic era, ignited the first sparks of bucolic poetry through his Idylls (set in Sicily in contrast to Alexandria of Ptolemy II Philadelphus).5Donna L. Potts, Contemporary Irish Poetry and the Pastoral Tradition (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2011), 1. This type of nature-describing poem gives the enthusiastic audience a sense of idealization, nostalgia, and escapism.6Casteel, “New World Pastoral,” 13. The homely atmosphere of the village is imbued with a sense of sanctity, where all its inhabitants are free from sin. It is an ideal place, a refuge against disruptive forces for those seeking restoration.7Greg Garrard, Ecocriticism, 3rd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2023), 56.

The distinguishing characteristic of pastoral poetry, when it was introduced into the Latin world by Virgil (70–19 BCE) through his Eclogues, is its direct connection to the shepherd’s lifestyle as a literary convention. From a Virgilian perspective, the conventions of pastoral poetry can be encapsulated in the formula: “The poet represents (himself as) a shepherd or shepherds.”8Paul Alpers, What Is Pastoral? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 185. Therefore, following Virgil’s model leads us to “represent” the behavior of nature’s inhabitants.

The Romantics also demonstrated a strong inclination toward the pastoral tradition and called poets the “guardians of nature.”9Friedrich Schiller and Julius A. Elias, Naive and Sentimental Poetry, and, On the Sublime: Two Essays (New York: F. Ungar, 1966), 24. In their encounter with the Industrial Revolution, the Romantics sought a poetry that could simplify Bildung10“The Education of Humanity, the Development of All Human Powers into a Whole” in Frederick C. Beiser, The Romantic Imperative: The Concept of Early German Romanticism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 22. and beautify the world. They revived Theocritus—the creator of bucolic poetry that expresses rural folk culture—from the pages of history.11Halperin, Before Pastoral, 56. Thus, what was once dedicated exclusively to rural and shepherd life in classical pastoral poetry was fundamentally transformed into an exploration of nature and human nature.12For a philosophical analysis of why the Romantics, particularly Friedrich Schlegel, were drawn to pastoral poetry and regarded it as embodying modern elements and sentimental themes, see Beiser, The Romantic Imperative, 117.

All in all, the pastoral, as originally defined by the fathers of the genre (Theocritus and Virgil), is an imitation of rural life (including caring for the animals, singing or playing musical instruments, and making love), which remains abundant within the scope of its thematic content. Classical pastoralism, which persisted until the eighteenth century, was intended to vividly evoke a sense of nostalgia and primarily sought to express the absence or loss of nature.

Pastoralism in Modern Persian Poetry

With the arrival of modernity in Iran, Iranian poets began to reject the notion of progress in a romanticized manner. In contrast to the long-standing tradition of Persian classical poetry, which often criticized and vilified the rural village,13For a comprehensive analysis of the perspectives of major classical Persian poets regarding the dichotomy between the village and the city, refer to Suhrāb Yazdānī and Muhammad Rafīʿī’s article titled “Du′gānigī-i rūstā-shahr va sultah-ʾi guftimān-i shahrī; Bā taʾkīd bar shiʿr-i kilāsīk-i Fārsī” (“The village-city dichotomy and the hegemony of urban discourse; With emphasizing on classical Persian poetry”), Pazhūhish′hā-yi ʿulūm-i tārīkhī 10, no. 1 (Spring and Summer 1397/2018): 117–36. Nīmā Yūshīj (1276–1338/1895–1960) celebrated rural life and its people, viewing the city as a place of corruption, imitation, and deceit. In his famous poem “Khānah-i Sirīvīlī” (The house of Sirivili), which he regarded as his finest work, he equated the city and its inhabitants with Satan and his followers. The introduction of the poem states: “The story is a battle between Sirivīlī and the devil, and Satan’s subject”:14All translations of the poems presented in this study are done by the author.

This is one of the major modern encounters between Persian poetry and pastoralism, in which Yūshīj turns the language into a pastoral concept.15Nīmā Yūshīj, Majmūʿah-ʾi kāmil-i ashʿār [The complete collection of poems], ed. Sīrūs Tāhbāz (11th repr. ed., Tehran: Nigāh, 1390/2011), 243. The central issue in this poetry is the “own language” of rural people—that is, the figure escapes the multiplicity found in the language of city dwellers. Yūshīj’s pastoral even goes beyond constructing a distant, subjective utopia; it rejects such a retreat precisely because of the unnecessary blowing of horns. Nature becomes “charming and beautiful” through the unity symbolized by the bird’s language.

At a time when Nīmā was romantically escaping urban culture and fleeing toward rural and pastoral nature, Persian poetry enriched its experience by sanctifying nature. Yūshīj’s anti-urbanism paved the way for many poets to follow.

After Yūshīj, three major poets—Manūchihr Ātashī (1310–1384/1931–2005), Hūshang Chālangī (1320–1400/1941–2021), and Suhrāb Sipihrī (1307–1359/1928–1980)—made significant contributions to Persian pastoral poetry. Manūchihr Ātashī, as a follower of Nīmā Yūshīj’s blank verse, is known for evoking the nature of southern Iran (Dashtistān) in a nomadic, gypsy-like tone:16Manūchihr Ātashī, Majmūʿah-ʾi ashʿār [The collection of poems] (3rd repr. ed., Tehran: Nigāh, 1394/2015), 1:311.

In his pastoral poetry, he searches for childhood nostalgia:17Ātashī, Majmūʿah-ʾi ashʿār, 1:740.

He is someone who flees the city so much so that even the apples of the city gardens taste bitter. His poem “Bih samat-i sāyah′hā-yi banafsh” (Towards purple shades) captures such a condition with precision:18Ātashī, Majmūʿah-ʾi ashʿār, 1:740–41.

The pastoral poetry of Ātashī seeks to rediscover his lost identity by returning to his homeland and playing music with local, traditional instruments like the small flute (naylabak).

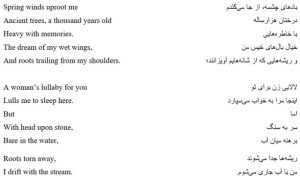

Hūshang Chālangī was from the Chāhār Lang (literally, “four shares”) branch of the Bakhtiyārī (also spelled Bakhtiari) tribe19The Bakhtiari tribe is divided into two main branches: Haft-lang (Seven four-legged) and Chāhār-lang (Four four-legged). The division originated from the tribe’s traditional taxation system. and was the last pastoral poet in Iran who was also a real shepherd, like Yūshīj and Ātashī. He had a considerable impact on major Persian poetry movements, including Mawj-i nāb (Pure wave) and Shiʿr-i dīgar (Other poetry). His description of unspoiled nature, meadows, grazing sheep, and shepherds’ fear of wolf attacks, give his poetry a primitive character. He successfully combined modern lyric poetry with a raw pastoral atmosphere. In addition, the “I” in Chālangī’s poetry becomes the voice of his ethnic group, bearing witness to its fate. What follows is an excerpt from his poem “Mīrās” (Legacy).20Hūshang Chālangī, Majmūʿah-ʾi kāmil-i ashʿār [The complete collection of poems] (Tehran: Afrāz, 1397/2018), 253.

The primitive pastoral of Chālangī reflects both the solitude and wandering of ethnic groups, even as they retreat to their homeland. In this context, the power of nature no longer guarantees the happiness of the tribe.

Suhrāb Sipihrī occupies a different position. He perceived God within nature. In other words, he envisioned a kind of existential unity:21Suhrāb Sipihrī, Hasht kitāb [Eight books] (Tehran: Murvārīd, 1389/2010), 272.

His approach to nature is one of becoming unified with it. He binds his existence to nature and channels all divine and metaphysical moments through it. Thus, Sipihrī’s pastoral is imbued with mysticism and meditative qualities. This invites a mention of a distinct form of “Oriental”22Here, “orient” thinking lies versus “occident” ones. This word highlights spirituality, mysticism, divinity, wisdom, and omnipresence of God in all objects and nature. To know more, see Suhrāb Sipihrī. The Expanse of Green: Poems of Sohrab Sepehry, trans. David L. Martin (United States, pub. by author, 1988). pastoral:23Sipihrī, Hasht kitāb, 372.

Sipihrī even condemns the use of shoes for severing the connection between the feet and the earth:

Barefooted state was a blessing that was lost. Shoes are remnants of Adam’s effort to deny the fall of man, an allegory for the sorrow of separation from paradise. There is something satanic in the shoe. It disrupts the healthy conversation between the earth and the feet.24Sipihrī, Hasht kitāb, 37.

Attending to the essence of nature in mystic-pastoral poetry—which, in reverence for the natural world, treats it as a repository of human secrets—positions Sipihrī, whether consciously or not, as a pioneer of eco-pastoral poetry in Iran. His harmonious relationship with nature and his commitment to preserving the earth’s laws and respecting nature are especially noteworthy. As he writes, “I should remember not to do anything against the law of the earth.”25Sipihrī, Hasht kitāb, 354. His environmental sensitivity, particularly toward for water, is clearly expressed in lines such as: “An empty can wound Joey’s throat” or “Don’t muddy the water, as if a pigeon were drinking downstream.” He even situates his pastoral utopia beyond the seas, envisioning:26Sipihrī, Hasht kitāb, 368.

According to Sipihrī aesthetic, human beings should be fully immersed in nature, where there is no anger and hatred:27Sipihrī, Hasht kitāb, 288.

In addition, for Sipihrī, nature is also a rich source of knowledge for humankind:28Sipihrī, Hasht kitāb, 424.

Taken together, the central role of nature as a source of inspiration, knowledge, wisdom, and a model for authentic life, which is often whispered in Sipihrī’s poetry, should be understood in relation to his interest in mysticism.29See Sipihrī, The Expanse of Green.

Surprisingly, among Persian women poets, particularly after Yūshīj, few are recognized for engaging directly with pastoral themes. One underlying reason is that most of them followed the stylistic and thematic path of Furūgh Farrukhʹzād (1313–1345/1934–1967), who was primarily a poet of the city. While their poetry includes natural imagery, it does not frame nature as a pastoral concept. However, one notable exception is Laylā Mahbūbī, who stands out for her emphasis on nature, land, and femininity within a pastoral framework. The heroine of Mahbūbī’s poem is a landless woman who is continually alienated by nature, which is a rare experience to find articulated in Persian women’s poetry. The following section reflects on key aspects of Mahbūbī’s life and background. It is followed by three sections analyzing the three themes—nature, land, and femininity—as developed in her two published poetry collections.

Laylā Mahbūbī’s Life and Background

Laylā Mahbūbī was born on Shahrīvar 1, 1348/ August 23, 1969, in Sari, Mazandaran province. Her grandmother was from Baku, Azerbaijan; she married an Azeri businessman and migrated to Iran. Due to the closing of the border, she was never able to return to her homeland. Mahbūbī’s mother spent her childhood and adolescence in a village in the Mughan plain. After a severe drought, the family relocated to Rasht and Mazandaran. Despite the moves, Mahbūbī’s mother always had a deep connection to her homeland, expressing a desire to have soil from her native land sprinkled on her face after death. Mahbūbī attended school through the assistance of a relative, as education for women was uncommon in most nomadic families. She has since earned a master’s degree in history and currently works as a teacher.30Extracted from an in-person interview with Laylā Mahbūbī on 31/4/2024.

Figure 2: Laylā Mahbūbī. Photo by Vahid Aminizadeh Yazdi

Mahbūbī remains continually drawn to the sense and idea of a motherland that she inherited from her mother’s stories. She regards kūch (migration) as a part of her family’s historical lineage. In the introduction to her book Bih zakhm′hā-yam surmah mīʹkishad, zanī, she reflects:

I came to understand the concept of land when, upon her death, my mother brought a handful of soil from her hometown, carried from this side of the Aras [River] to cover her face… I was searching for a lullaby in my mother’s Ukhshāmā.31Ukhshāmā is a traditional Turkish lament song characterized by its intense, burning emotion, expressing the deep sorrow and grief associated with the loss of loved ones. Mahbūbī, Bih zakhm′hā-yam surmah mīʹkishad zanī, 5.

Consequently, Mahbūbī sees poetry as a fitting medium for exploring and reclaiming her motherland. However, she remains hesitant to fully trust words as authentic evidence of her origins. Similarly, in the introduction to her poetry collection Bī huzūr-i ghubār-i dast, she writes: “Where am I to find my home? Words slip away. You didn’t betray me with the sacred word, did you?”32Mahbūbī, Bī huzūr-i ghubār-i dast, 5.

A close reading of Mahbūbī’s poetry reveals three intertwined feminist pastoral themes: land, nature, and femininity. These themes are articulated from a feminist perspective. As Judith Butler explains, “when Beauvoir claims that ‘woman’ is a historical idea and not a natural fact, she clearly underscores the distinction between sex, as biological facticity, and gender, as the cultural interpretation or signification of that facticity.”33Judith Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” Theatre Journal 40, no. 4 (1988): 522. Mahbūbī’s poems similarly highlight the historical conditions of women who often suffer most from the consequences of war and displacement. Her poems demonstrate how the biological sex of a woman (i.e., body) is shaped and conditioned by gender as a socially and culturally constructed category. For example, the central figure of her poem are victimized women who uprooted by their land and indeed did not absorb by nature. They even do not play a mother-land role based on stereotype of women. The main reason may be that these desperate women are exposed to the trauma of rape under pressure of the men hegemony. These following themes will excavate such claims based on Mahbūbī’s verses.

The Theme of Land

Loss and separation from the land are recurring themes in Mahbūbī’s poetry. Land functions as a core element of individual identity, anchoring the self in memories that connect one to the past. When individuals become estranged from the past, their sense of identity is similarly threatened.34The land not only is the place of our living but also that of our being. To know more about the relationship between place and being, see Edward S. Casey, Getting Back into Place: Toward A Renewed Understanding of the Place-World (Bloomington, IN, Indiana University Press, 1993). Mahbūbī uses poetic language to articular the sorrow of displacement, demonstrating how the memory of land can unsettle the emotional and psychological well-being of women, figures who, in her work, serve as agents of humanity. For example, the poem “Īstgāh” (Station) portrays a woman uprooted from her homeland. This sense of alienation is mediated through the image of a train—invoked in a manner reminiscent of Romantic poetry—as a symbol of modern estrangement:35Mahbūbī, Bih zakhm′hā-yam surmah mīʹkishad zanī, 19.

Emigration entails a sense of uprootedness. The “roots” in this context are history, culture, background, traditions, and the formative experiences that shape our present identity. Just as it is impossible for a person to entirely erase memory, the central figure of a poem by Mahbūbī, despite being separated from a fixed, immovable homeland, continues to bear the weight of that land on her shoulders. This enduring connection to place is also poignantly expressed in the poem “Border”:36Mahbūbī, Bih zakhm′hā-yam surmah mīʹkishad zanī, 32–33.

Since the border severs the connection to the past, no new land can truly replace the motherland. Although roots are carried upon the shoulders, they remain incapable of taking hold in foreign soil, because not every lullaby is the voice of a mother, soothing into peaceful sleep. A lullaby in a strange land may offer a temporary comfort, but it never heralds a genuine reawakening.

The “woman” in Mahbūbī’s poem, as she distances herself from her homeland and enters the urban environment, endures negative and painful experiences. The poem “Kūchah-ʾi bī-nām” (A nameless alley) poignantly reflects this theme: 37Mahbūbī, Bih zakhmʹhā-yam surmah mīʹkishad zanī, 17.

Thus, the “woman” is wounded in the city’s nameless alley. She is lost and confused and has not regained her identity. This wound even penetrates her clothing. For example, wearing a skirt is a cherished characteristic of nomadic women in Iran. In Mahbūbī’s poetry, objects and elements of nature are not inert and this sense of estrangement and wounded identity is vividly conveyed through her evocative imagery, as seen in the following lines from “Nā′shinākhtah” (Unknown)38Mahbūbī, Bih zakhmʹhā-yam surmah mīʹkishad zanī, 52. and “Jā′māndah′hā” (The ones left behind)39Mahbūbī, Bih zakhmʹhā-yam surmah mīʹkishad zanī, 34. poem:

Separation from the land in Mahbūbī’s poetry is not solely attributed to the urbanization or technological change; nature and its elements also intensify this division. In her poem, “Shallāq-i marz bar rūd navākhtah mīʹshavad” (The border whip is played on the river),40Mahbūbī, Bih zakhmʹhā-yam surmah mīʹkishad zanī, 58. soldiers are not depicted as physical beings but, becoming invisible to the human eye, they allegorically attack the land itself:41Mahbūbī, Bih zakhmʹhā-yam surmah mīʹkishad zanī, 16.

In sum, while Mahbūbī’s personal experience of migration may reflect the specific trauma of women uprooted from their homeland, her poetry also speaks to a broader, universal condition—the dislocation of humanity from its origins. Her verses capture the tragic fate of those who, believing themselves to be emancipated, find themselves instead consumed by another kind of fire: one born not of liberation, but loss and estrangement.

The Theme of Nature

Traditional pastoral poetry typically centers on the retreat or return to nature, wherein nature becomes, often unconsciously, a sacred refuge or healer for people alienated by modern, urban life. From its early origins to the Romantic revival, nature has consistently been praised and idealized. Romantic poets believed ancient poets imitated nature directly through an immediate unity with it, whereas modern poets idealize nature due to a lost connection, Similarly, Persian pastoral traditions portrayed nature as a nostalgic point of reference.42For theory of “imitation” versus “idealization” of nature among Classical versus Romantic Poets such as Wordsworth and Coleridge see M.H. Abrams, The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1953.) However, Laylā Mahbūbī diverges sharply from both Western and Iranian pastoral conventions, portraying nature as an ambivalent, even negative, force in her poetry. In Mahbūbī’s poems, natural elements, including wind, water, rain, spring, trees, and sea, do not merely provide setting; they obscure human identity and amplify suffering. An illustration of this appears in the following lines of “Daryā′navardān” (Sailors) poetry: 43Mahbūbī, Bih zakhmʹhā-yam surmah mīʹkishad zanī, 49.

Here, nature, specifically the wind, emerges not as a source of comfort or renewal but as a disruptive and disorienting force. It strips individuals of direction, memory, and belonging.

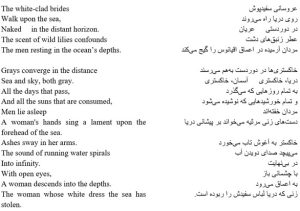

Mahbūbī’s poem “Dūr′dast-i ʿuryān” (Naked in the distant horizon) marks the pinnacle of her exploration of nature’s darker dimensions. Here, the traditional symbols of peace and tranquility, such as the sea and the sky, are depicted in shades of gray, signaling a profound inversion that reveals nature’s underlying negativity and despair within her poetic vision:44Mahbūbī, Bih zakhmʹhā-yam surmah mīʹkishad zanī, 66-67.

Here, nature assumes a malevolent mediating role, even defiling a woman’s skirt. Consider how the gray sea seeks to steal her white, pristine skirt, a gesture that may symbolize the loss of a woman’s sacred innocence. While men are depicted as “resting” or “asleep,” women become victim of nature’s unpredictable cruelty. The sea also seizes her bloodstained dress and skirts, its twisting motion ending in infinite disappearance, an abyss so deep that it consumes the sun like a cosmic void.

Indeed, in Mahbūbī’s poetry, nature is ruthless, and one cannot expect salvation from it. She cautions in “Āghūsh-i āsimān” (The sky’s embrace) poem: 45Mahbūbī, Bih zakhmʹhā-yam surmah mīʹkishad zanī, 75.

Here, nature is not restorative; it is a source of wounds and discomfort, beyond the reach of divine intervention or faith. In the poem “Tavāf-i bād” (Circumambulation of the wind), even the temple, a sacred space of worship connecting earth and sky, is rendered powerless. It stands impassive before the wind that seized the woman’s life and danced around her, an image where the sacred is overwhelmed by nature’s blind force:46Mahbūbī, Bih zakhmʹhā-yam surmah mīʹkishad zanī, 68-69.

Women are subject to the forces of nature, while sacred symbols such as temples continue to burn frankincense in their consecrated space, seemingly satisfied with the act of circumambulation. What wind can twist the lips of girls into bruised bitterness? Why does poetry not offer the women who are victims of nature to the care of metaphysical forces, so that through divine intervention evil might be overcome? The apathy and neutrality of sacred forces in the face of evil is hardly unprecedented. Indeed, the theological response to Auschwitz resulted in a comparable outcome: there, minorities, including those deemed divinely chosen, became victims of humans who claimed racial superiority. In Mahbūbī’s work, womanhood itself is cast as an original sin. A woman is objectified as a sex slave. The bruised, bitter lips of young girls are born of their “precocious intuition,” akin to precocious puberty in boys, an early self-awareness of being female, of being objectified. This fledgling consciousness is entrusted to a woman who has already perished, her body a corpse sustained only by destruction.

In the poem, the destinies of women’s and girls’ bodies are subtly depicted as ordained by divine will, enacted through the very forces of nature. Nature thus becomes an instrument of the divine, and women its unwitting victims. In this vision, suffering becomes fated, and rebellion against either nature or metaphysical inevitability is rendered impossible for the women in Mahbūbī’s poetry.

The Theme of Femininity

Historically, women have been largely absent from pastoral poetry, often depicted as passive objects like sexual archetype.47Halperin, Before Pastoral, 64. Mahbūbī’s pastoral poems place the women at the forefront, a significant achievement in Persian poetry. By reclaiming femininity and presenting women’s perspectives on nature, she challenges traditional narratives. However, the women in her poems are not portrayed as triumphant; rather, they are depicted as distrusted, marginalized, and wounded. In these works, “woman” is scarred by both nature and the land she inhabits, having suffered the devastating consequences of rape and bloody wars. Upon closer examination, it becomes evident that this woman’s destruction is not solely the result of external conflicts; she is consumed from within, falling victim to her own womanhood. This theme is poignantly explored in the poem “Gūr-i gharīb-i mādar” (Mother’s strange grave):48Mahbūbī, Bih zakhmʹhā-yam surmah mīʹkishad zanī, 16-17.

From a feminine perspective, the “I” encompasses the sufferings of other women who “have been lost in me.” This “I” bears the weight of a brother’s coffin on her shoulders. Her body transforms into a burial ground where deer—symbols of innocence and purity— are interred. But who is this “I”? She is a woman who perceives herself as a victim of war and its soldiers; a woman without a homeland, unaware of her mother’s resting place; a woman who, unable to bear life, finds her body has become a tomb that holds the waters of the dead. This poem is a bitter reminder of a catastrophic event, asserting that women do not embody the role of sacred mothers during wartime but instead bear the additional burden of sexual assault on their bodies.

In the poem “Bī āshiyānah” (The nest-less), the fountain fails to cleanse the woman’s body of its taint. The women depicted in these poems are helpless in their eternal suffering, surrendering to their fate. A note preceding the poem quotes a passage from the Gospel of Matthew: “Foxes have dens and birds of the sky have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to rest his head” (Matthew 8:20). Laylā Mahbūbī selects a verse that alludes to Christ’s homelessness and wandering. However, the title does not use the terms “home” or “homelessness,” instead, it uses “the nest-less.” In doing so, Mahbūbī invokes the image of a bird or hen whose head must be severed, symbolically sacrificed offered as a sacrifice to the gods. 49Mahbūbī, Bih zakhmʹhā-yam surmah mīʹkishad zanī, 30–31.

This poem refers to Tbilisi and Georgia, which was attacked (1795) during the reign of Aghā Muhammad Khān Qājār. However, the poem does not focus on recounting historical events. Instead, it evokes the memory of a woman in Tbilisi who was sexually assaulted by Qājār soldiers.50Based on historical accounts, “15,000 beautiful Georgian women, girls, and boys were taken captive, and the army was permitted to use them in various forms of bondage.” See Mahmūd Mīrzā Qājār, Tārīkh-i Sāhib Qirānī (History of the Sāhib Qirānī), ed. Rizā Samarī Hājī-Āghā (Tehran: Safīr-i Ardahāl, 1396/2017), 106–07. However, recent studies consider these figures to be exaggerated, suggesting that such numbers were likely used to underscore the king’s authority and power. For a detailed discussion, see Ghulām-Husayn Zargarī′nijād, Bar-āmadan Qājār: Tārīkh-i Īrān az pāyān-i ʿasr-i Safavī tā qatl-i Āqā Muhammad Khān Qājār (The rise of the Qajars: History of Iran from the rnd of the Safavids to the assassination of Āqā Muhammad Khān Qājār) (Tehran: Nigāristān-i Andīshah, 1402/2023). In parallel, the poem introduces another image: an animal nursing a gazelle. The suckling animal symbolizes motherhood, yet its own offspring has been beheaded, and it now cares for another whose mother has been torn apart. This image draws a comparison between the suffering of animals and women, with both lives marked by pain, loss, and brutality. Moreover, nature does not play a positive role here, as emphasized by the line, “Does not wash away in any spring’s water.”

A Feminist Pastoral Perspective

By examining Laylā Mahbūbī’s treatment of land, nature, and women, it becomes clear that nature symbolizes human nature in her work. Mahbūbī uses natural elements to highlight how women, as both members of society and living beings, are incapable of resolving the gendered challenges imposed upon them by historical constructs. This marks a new form of expression in Persian poetry, where pastoral themes are used to critique societal issues. Although at first glance, these poems may not seem explicitly socially conscious, the intersection of social issues with pastoral poetry is not a novel concept in Western literature. Mahbūbī’s distinct contribution lies in her focus on the negative and silent aspects of nature, which reflects how societal challenges are internalized. In her work, natural elements mirror the anti-feminine laws imposed by oppressive forces. In a society that continually seeks to reject feminine identity, a woman is left without a sense of belonging and selfhood. She cannot find solace in nature, nor can she use it as a refuge to shield her struggles. In these poems, Mahbūbī shows that nature and human nature are inseparable. These poems did not emerge in a vacuum; they reflect centuries of entrenched misogynistic thought that continues to shape society, casting a long shadow over these poems. We are drawn to these poems because of the deep resonance they have with the ongoing struggles of humanity, as the themes of oppression, loss, and displacement transcend time.

Conclusion

Laylā Mahbūbī’s pastoral poetry does not adhere to the traditional, regressive pattern of retreating to nature or the village; rather, she emphasizes the inevitable fate of pastoral women who endure suffering in a historical situation. Mahbūbī advances pastoral poetry by offering a fresh perspective on natural concepts utilized in her work. She rejects both the Hellenistic approach, which seeks to elevate nature to a sacred status through nostalgic depictions, or the Romantic approach, which returns to natural life as a foundation for Bildung or personal development and self-cultivation. Instead, she focuses on the presence of women as “the other” and sexual objects, overlooked by natural elements.

Traditionally, pastoral poetry has served as a refuge, reflection, requiem, and reconstruction.51Terry Gifford, “Pastoral, Anti-Pastoral, and Post-Pastoral,” in The Cambridge Companion to Literature and the Environment, ed. Louise Westling (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 17–30. However, deviating from conventional pastoral traditions, Mahbūbī employs pastoral elements allegorically, reinterpreting the concepts of land, nature, and femininity. Her work amplifies the plaintive voices of victimized women, rendering her poetry profoundly desperate, bitter, and dark. This bitterness, stemming from a separation from the motherland, is neither contrived nor merely technical. Instead, it is rooted in the lived experience (das Erlebnis) of a poet who not only witnesses the suffering of victimized women throughout history but also deeply identifies with their plight. Mahbūbī’s experience as a diasporic woman and her study on the bitter events enable her to bear witness to the impending catastrophe pneumatically.

The women, though described as broken, will one day be emancipated by their femaleness. Since “many women have been lost in me,” those women will eventually be found.