Zhālah Isfahānī, Iranian Poet, Scholar, and Activist

Figure 1. Portrait of Zhālah Isfahānī. Image source: Jaleh Esfahani Cultural Foundation.

The poet known throughout her career as Zhālah Isfahānī (1300–1386/1921–2007) was born in Isfahan and officially registered as Itil Sultānī. In her autobiography, Sāyah-ʾi sāl’hā (The shadow of the years, 1379/2000), in which she refers to herself in the third person as Mastānah, she provides detailed reflections on her given name and the pen name she later adopted.1Zhālah Isfahānī, Sāyah-ʾi sāl’hā: Sar’guzasht-i Zhālah Isfahānī [The shadow of years: Autobiography of Zhālah Isfahānī] (Essen, Germany: Nima Verlag, 1379/2000), 58–59. The English name Itil (or Ethel) had been chosen by her father, who had known an English nurse in Isfahan by that name, but she was commonly called Zhālah. Despite her father’s disapproval, her strong-willed mother ensured that Zhālah attended school and supported her when she rejected an early arranged marriage to continue her education.

The girls’ school she attended in Isfahan, Bihisht’āʾīn, did not offer the final year required for graduation, so she later completed her studies at Nūrbakhsh High School in Tehran. Again, against her father’s wishes, Zhālah applied for a position at the bank and began working, becoming one of only a few young women in Isfahan employed outside the home. Another such figure was Shahnāz Aʿlāmī, also a poet, whose life and career bore similarities to Zhālah’s.

Although Zhālah may have shown some promise in composing poems from the age of seven, she usually identified a ghazal written in the sixth grade (at age thirteen) as her first poem.2Zhālah Isfahānī, Sāyah-ʾi sāl’hā: Sar’guzasht-i Zhālah Isfahānī [The shadow of years: Autobiography of Zhālah Isfahānī] (Essen, Germany: Nima Verlag, 1379/2000), 89. During her final years of high school, her teachers and classmates knew that she wrote poems, and she was frequently invited to read her poems at school events. Around this time, her poems and literary sketches also appeared in local newspapers.

Figure 2: Young Zhālah (1323/1944?). Photograph from her first book of poems, Gul’hā-yi khvud’rū. Image source: Jaleh Esfahani Cultural Foundation.

After Parvīn Iʿtisāmī, whose Dīvān (Book of poems) was published in 1315/1935 (when she was thirty, only after her short-lived marriage and divorce), Zhālah was the first Iranian woman to publish a book of poems (1323/1944). She was nearly twenty-three years old and unmarried, which made this even more unusual and revolutionary. The book Gul’hā-yi khvud’rū (Wildflowers) was published with the assistance of Bānk-i Millī-i Īrān (National Bank of Iran), where she was employed, and the poet was simply identified as “Zhālah.” This was one year after she had met Shams al-Dīn Badīʿ Tabrīzī, a young air force officer and pro-Soviet Tūdah Party affiliate, whom she married.3Isfahānī, Sāyah-ʾi sāl’hā, 139.

Gul’hā-yi khvud’rū, a book of about sixty pages, contains ninety-eight poems, most of them ghazals, preceded by a short introduction and followed by a one-page prose note, apparently in memory of her mother. The dedication page describes the book as “a bouquet of flowers to her mother’s tomb.” A footnote to a poem reveals that her mother died in Khurdād 1320/June 1941.4Isfahānī, Sāyah-ʾi sāl’hā, 31.

Except for a few undated poems, the remainder are dated, most of them composed in the years immediately preceding the book’s publication. At least one short ghazal of five couplets, however, is dated 1316/1937, when she was barely sixteen years old, and a few others were composed in 1317–1319/1938–1940.

Figure 3: Title page from the book Gul’hā-yi Khvud’rū, Tehran, 1324/1945.

Even in her first collection, Zhālah displays gradual artistic development, with the later works in the volume revealing a marked maturity in both poetic technique and the cultivation of her character and self-confidence. Several poems engage with themes of God, faith, and praise of chastity, as in the final couplet of a ghazal where she, following the convention of traditional ghazal, employs her takhallus, or pen name, “Zhālah”:

دل من «ژاله» تابناک بود / کاندرآن غیر نور یزدان نیست

My heart, Zhālah, is filled with light

For it contains nothing but the light of God (Yazdān).5Zhālah Isfahānī, Gul’hā-yi khvud’rū (Tehran, 1324/1945), 3.

In this ghazal, she expresses pride and joy that her heart “does not go after desire and lust and does not follow the biddings of the devil.”6Isfahānī, Gul’hā-yi khvud’rū, 3.

نرود در پی هوی و هوس/ پیرو امر و نهی شیطان نیست

It does not pursue desire and lust,

Nor does it obey the commands and prohibitions of the devil.

Ironically, and in compliance with cultural norms that regarded the use of make-up inappropriate for unmarried girls, she writes in an undated ghazal that “beauty is not in adorning and pluming oneself” (zībāʾī bih khvud’ārāʾī nīst):

گرد الوان چه زنی بر رخ پاکیزهٔ خویش

روغن و رنگ ترا مظهر زیبائی نیست

روی گلگون تو گر ساده نباشد ای مه

عاشق نرگس مستت دل سودائی نیست

Why do you put these colourful powders on your clean face?

It is not colour and oil that are considered as signs of your beauty.

If your rosy face is not simple [i.e., free of make-up], O Moon,

No heart will madly fall for your drunken, narcissus-like eyes.7Isfahānī, Gul’hā-yi khvud’rū, 24.

In another poem dated 1322/1943, Zhālah takes a critical stance against women’s hijab. She demonstrates an increasing awareness of social issues and women’s rights in later poems in this book. On the whole, the poet aligns herself increasingly with the “social/political ghazal” of the time, a mode that had emerged with the poets of the Constitutional Revolution (ʿĀrif, ʿIshqī, Bahār) and remained popular during those turbulent years in Iran’s history. The influence of these poets, especially ʿIshqī, can be discerned both in nationalist sentiments of her poetry, which in subsequent decades would be blended with or replaced by internationalist concerns, and in her diction and style. The last piece in the volume (preceding the concluding prose note) is a longer poem, dated 1322/1943, composed as an opera for performance at school, undoubtedly influenced by similar works by ʿIshqī.

Some of Zhālah’s poems lamenting social injustice, like the 1320/1941 poem, “Kūdak-i yatīm” (Orphaned child), which uses a moderately new stanzaic form (ab ab cc), are reminiscent of poems by Lāhūtī, Parvīn, and Afrāshtah, as well as of the early poems of the younger Sīmīn Bihbahānī in the 1320s/1940s to 1330s/1950s.

In Khurdād 1325/June 1946, the Perso-Soviet Society of Cultural Relations (Anjuman-i Ravābit-i Farhangī-i Īrān va Ittihād-i Jamāhīr-i Shawravī) convened a gathering that came to be known as the first “congress” of Iranian writers (Tīr 4/June 25 to Tīr 12/July 3). The event was chaired by Muhammad Taqī Bahār (1265–1330/1880–1951), then the undisputed Malik al-Shuʿarāʾ (poet laureate or “King of the poets”) of Iran. Zhālah’s participation, indeed as the youngest of the seventy-eight participants, many of whom were already established poets, writers, and scholars, demonstrates that she had begun to secure recognition as a promising young poet following the publication of her first book.8Shadab Vajdi, “ESFAHANI, Jaleh,” in Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2009, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/esfahani-jaleh/. She does not indicate in her autobiography whether Badīʿ Tabrīzī’s political affiliations, or her own nascent leftist sympathies, influenced her selection. She later writes that she, “like so many others of her fellow countrymen, without full awareness of what was going on in those years in Soviet society, was fascinated by socialist ideals.”9Isfahānī, Gul’hā-yi khvud’rū, 184.

Zhālah early recognition and relative fame in Iran proved short lived. Her husband, Badīʿ Tabrīzī, was imprisoned for a year and subsequently dispatched to Tabriz in Azerbaijan, then under the administration of the pro-Soviet Firqah-ʾi Dimukrāt-i Āzarbāyjān (Azerbaijan Democratic Party). Zhālah had scarcely joined him there when the central army intervened, reoccupied Azerbaijan, and initiated a violent purge of the leftist opposition. This forced Zhālah and her husband to flee Iran, seeking refuge in the Soviet Union (Baku).

In her autobiography, Sāyah-ʾi sāl’hā, Zhālah recounts her years of exile in the Soviet Union and later in London, as well as her various occupations and activities. This forced emigration nearly erased her presence from the landscape of contemporary Persian poetry in Iran for decades, preventing her from achieving the stature later attained by her peers who remained in Iran, or the next generation of poets.

Cold War politics in the region, the role assigned to Iran (especially after the 1332/1953 coup against the nationalist Premier Muhammad Musaddiq) by the West, and the sweeping censorship of works deemed sympathetic to leftist ideas, or the Soviet Union erected an iron wall between Zhālah and Iran. She suffered a fate similar to that of the great Constitutional era poet, Abū al-Qāsim Lāhūtī, who left Iran in 1301/1922. For Zhālah, exile did not merely mean being unpublished in Iran or deprived of a direct Iranian readership; it also severed her from the dynamic life of Persian literature, its flourishing creativity, and the vibrant exchanges in the literary journals and periodicals. Despite her efforts to maintain sporadic contact with fellow poets in Iran, this separation inevitably left its mark on the development of her poetry.

Although not cited with bibliographical detail in other sources (neither in Iranica or on her website), Zhālah mentions in her autobiography a collection of poems published in Tajikistan, titled Mādarān sulh mī’khvāhand (Mothers want peace), as well as another volume published in Baku, Azerbaijan (in Azeri translation) or in Russian.10Isfahānī, Gul’hā-yi khvud’rū (Tehran, 1324/1945), 212–13. While continuing her studies (she earned a PhD in literature), raising children, and attending writers’ conferences, she may have enjoyed a measure of recognition in the Soviet Union as “the sole female face of Persian poetry.”11Vajdi, “ESFAHANI, Jaleh”. Nevertheless, as noted above, she was already a forgotten name in Iran.

Translations of the works of the nineteenth-century Russian realist authors enjoyed popularity in Iran during the 1330s–1340s/1950s–1960s. They were permitted largely because they belonged to the pre-Bolshevik period. This situation also enabled Soviet publishers such as Progress, supported by exiled Iranians, to produce and distribute Persian translations of Russian literature in Iran. In 1965, however, a book of poems in original Persian appeared in a few Tehran bookstores. Published by Idārah-ʾi Intishārāt-i Dānish and titled Zindah’rūd (Living river), a shortened form of Zāyandah’rūd (“life-giving river,” always associated with the city of Isfahan),12Zhālah Isfahānī, Zindah’rūd (Moscow: Idārah-ʾi Intishārāt-i Dānish, 1965). the volume featured on its dedication page Rūdakī’s famous line yād-i yār-i mihrabān āyad hamī (“Memories of the kind beloved are coming”), a verse resonant with connotations of homesickness and remembrance of Iran’s past. The poet was identified simply as “Zhālah.” No biographical note accompanied the book, nor was there any mention of the earlier collection (Gul’hā-yi khvud’rū). Even the photograph bore little resemblance to the free-spirited young woman; appearing instead as the formal portrait of a Soviet female cadre (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Photograph of Zhālah from the book Zindah’rūd.

The publication of limited distribution of Zindah’rūd cannot be regarded as a revival of Zhālah’s reputation, for few remembered the brief career of the young poet. The book, Zindah’rūd, was markedly different from her first collection: not only in appearance and typesetting (typical of Soviet-published Persian books) but also in content. Its 130 pages comprises fifty-two poems, of which only one poem is a ghazal;13Zhālah Isfahānī, Zindah’rūd (Moscow: Idārah-ʾi Intishārāt-i Dānish, 1965), 41. the rest are Nimaic (free verse) or stanzaic experiments. In the mid-1350s/1960s, when Zindahʹrūd reached Iran, major poets such as Ahmad Shāmlū, Mihdī Akhavān Sālis, and Furūgh Farrukhʹzād had already moved beyond the “romantic” stage of early modern Persian poetry. Zhālah’s turn from ghazal to a romantic, sentimental, and only moderately “modern” style, though a step forward, came too late to be taken seriously by the literary mainstream. Some poems reveal the influence of poets like Nādir Nādirpūr,14Isfahānī, Zindah’rūd, 42. while her ventures into free verse remained tentative and not yet fully realized. Often homesick (recalling Isfahan’s Zāyandah’rūd when watching a river in Prague),15Isfahānī, Zindah’rūd, 23–24. she also wrote poems celebrating her adopted homeland, including verses in praise of Soviet astronauts.

Figure 5: Cover of the book Zindah’rūd, Moscow, 1344/1965.

Figure 6: Title page from the book Zindah’rūd, Moscow, 1344/1965.

The most memorable poem in this collection, combining artistic craft with sincerity, is the opening piece, “Sitārah-ʾi qutbī” (Polar star), dated 1338/1959. It reflects how, in those years, Russia’s space achievements inspired even poetry with celestial imagery during those years:

بخند بر من پرسوز ای ستارهٔ قطبی

تو التهاب چه دانی؟ که روشنائی سردی

من آن شرارهٔ سوزان قلب گرم زمینم

تو آن ستارهٔ آسودهٔ سپهرنوردی.

چه سود آنهمه زیبائی خموش فسونگر

اگر نداری سوزی و گر نداری دردی؟

چه ارزشی بود آن زندگانی ابدی را

اگر که نیست امیدی و گر که نیست نبردی؟

نمیدهم به تو یک لحظه عمر کوته خود را

هزار قرن اگر زندگی کنی و بگردی.

متاب بر من بیتاب ای ستارهٔ قطبی

که من شرارهٔ گرمم تو روشنائی سردی.

Laugh at me, who am aflame, O Polar Star!

What do you know of passion, you cold light?

I am that burning sparkle of the warm heart of the Earth;

You are that tranquil star roaming the galaxy.

What benefit is all that bewitching, silent beauty

If you do not burn and if you do not feel pain?

What value has that eternal life

If there is no hope and no challenge and fight?

I would not exchange even a moment of my brief life

For yours, even if you live and turn for millennia.

Do not shed your light on me, who am impatient and lightless,

O Polar Star! For I am a warm spark and you are a cold light.

Left-leaning intellectuals in Iran, who read eagerly, or at least curiously, anything published in the Soviet Union, found these poems by an exiled Iranian called “Zhālah” noteworthy. An emotional socio-critical poem like “Kūdak-i qalamzan” (Child engraver), dated 1327/1948 and published with several typographical errors, critiqued child labour in Isfahan’s craft industries and may have influenced writers such as Samad Bihrangī. The poem, which may have been known in Iran even before the publication of the book, ends with the following stanza:

امروز نقش میبند با چکّش ظریفت

فردا شوی چو مردی نامآور و توانا

با چکّش بزرگت بر فرق دشمنان کوب.

روز تو است فردا.

Today, engrave designs with your tiny hammer.

Tomorrow, when you are a strong man known to all,

Strike with your heavy hammer on the head of the enemy.

Tomorrow will be your day.

Among literary critics and in literary circles, however, the book did not mark a breakthrough for Zhālah. She remained absent from major anthologies of contemporary Persian poetry and from critical studies of modern literature in Iran.

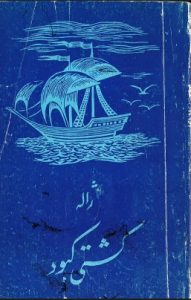

In 1357/1978, as Iran approached revolution, Zhālah published Kishtī-i kabūd (Blue ship) in Dushanbe, Tajikistan.16Zhālah Isfahānī, Kishtī-i kabūd [Blue ship] (Dushanbe: ʿIrfān, 1978). This slim volume of thirty-four pages contained sixteen poems, though it was likely a selection from a larger number of poems intended for the book. Zhālah’s Majmūʿah-ʾi ashʿār (Collection of poems) lists thirty-three poems under the same title, suggesting an original total of thirty-six.17Zhālah Isfahānī, Majmūʿah-ʾi ashʿār [Collection of poems] (Tehran: Nigāh, 1384/2005). One of her most popular poems, “Shād būdan hunar ast” (Being happy is an art) first appeared here,18Isfahānī, Kishtī-i kabūd, 7. its title added in her own handwriting, perhaps at the last minute. In “Man qanārī nīstam” (I am not a canary),19Isfahānī, Kishtī-i kabūd, 21. she asserts that the reader should not expect delicate love lyrics; her poems are the angry songs of a people weary of waiting. Though far away, she insists she has never been oblivious to her country’s fate, presenting herself as a poet of the “era of passage” (dawrān-i ʿubūr).

Figure 7: Cover of the book Kishtī-i Kabūd (Blue Ship), Dushanbe, 1357/1978.

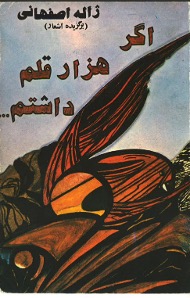

Zhālah recounts in Sāyah-ʾi sāl’hā the delays in publishing her next book of poems, Naqsh-i jahān (Image of the world, named after the historic square in Isfahan).20Zhālah Isfahānī, Sāyah-ʾi sāl’hā: Sar’guzasht-i Zhālah Isfahānī [The shadow of years: Autobiography of Zhālah Isfahānī] (Essen, Germany: Nima Verlag, 1379/2000), 263–64. It was eventually published in 198121Isfahānī, Sāyah-ʾi sāl’hā, 263. by Bungāh-i Nashriyāt-i Prugris (Progress Publishers) in the Soviet Union (she mistakenly records 1980 in her memoir), while in Tehran that same year Agar hizār qalam dāshtam… (If I had a thousand pens…) appeared.22Zhālah Isfahānī, Naqsh-i jahān [Image of the world] (Moscow: Bungāh-i Nashriyāt-i Prugris, 1359/1981); Zhālah Isfahānī, Agar hizār qalam dāshtam… [If I had a thousand pens…] (Tehran: Haydar Bābā, 1360/1981). The poet’s name was given simply as “Zhālah” in the book published in Russia, as in the earlier Zindah’rūd, whereas in Tehran it appeared as “Zhālah Isfahānī (Sultānī).” Both books were published as “selected poems,” and many of the same poems appear in both. Naqsh-i jahān contained ninety-eight poems and included no introduction or biographical note. Agar hizār qalam dāshtam…contained 145 poems and featured a preface by Ihsān Tabarī, then a member of the Central Committee of the Tūdah Party of Iran. Tabarī’s foreword, in line with the positions of the party, expressed some praise for the Islamic post-revolutionary government, perhaps to facilitate publication. While praising Zhālah’s poems, he also did not fail to add some mild criticism, finding her poetry lacking in depth of imagination compared with what her peers in Iran had achieved in their more successful works.23Ihsān Tabarī, “Foreword to Agar hizār qalam dāshtam…,” by Zhālah Isfahānī (Tehran: Haydar Bābā, 1360/1981), 6.

Figure 8 (left): Cover of the book Naqsh-i jahān, Moscow, 1359/1981. |

Figure 9 (right): Cover of the book Agar hizār qalam dāshtam, Tehran, 1360/1981. |

The publication of this volume coincided with Zhālah’s brief return to Iran following the Islamic Revolution of 1357/1979. Zhālah had returned to Iran full of hope and enthusiasm, probably expecting greater recognition and appreciation. However, she was soon disillusioned by the trajectory of the new religious autocracy. Although she refrained from writing openly about these experiences for obvious reasons, her son, Bīzhan later recounted that she had been arrested at some point during her stay in post-revolutionary Iran and spent a short time in jail.24Bīzhan, in an interview with Samuel Hodgkin. After two years, Zhālah left Iran once again, this time to settling permanently in London, where she had earlier sent her son to study. She remained there until her death in 1386/2007.

Zhālah never ceased writing poetry. In London, which had become home to a substantial Iranian community, she was able to find companionship among Iranian poets and writers living there as well as among politically like-minded opposition activists. Yet it was mostly the company of younger poets that provided her with hope, energy, and satisfaction. She increasingly turned to Nimaic and free verse forms, and at times experimented with poetry entirely free of traditional meters. In some poems, she moved stylistically closer to the next generation of poets, such as Ismāʿīl Khuʾī (1317–1400/1938–2021), who also lived in London, and with whom she frequently met at cultural gatherings. Although many might remember Zhālah for her more politically engaged poems, she was equally capable of composing moving, personal or contemplative poems even in her later years. One such example is the following short poem, written in 1377/1998, which reveals a markedly different voice from the conventional image of Zhālah:

Haves and have-nots25The original meaning of the Persian title is all a person’s belongings, especially when they do not amount to much.

Of haves and have-nots

I have memory and aspiration and

honor.

What I have not

or have not enough:

wealth

strength

and confidence.

With these haves and have-nots

Much like a child

Holding the hand of my mother – the earth –

I turn around the sun.

That’s all.26Zhālah Isfahānī, Shukūh-i shikuftan (Essen: Nima Verlag, 1381/2003), 38.

The books that Zhālah published after her immigration to London include:

- Khār’pusht (The hedgehog), London, 1983.27Zhālah Isfahānī, Khār’pusht [The hedgehog] (self-pub., London, 1983). A slim volume of just over thirty pages, it contains ten poems. The last poem, “Guzārish-i manzūm” (A report in verse), is composed of ten monologues by ten characters representing different social types disillusioned with the revolution. The book shows little editorial care and was issued without basic publication details—no date, publisher, or even the poet’s name. These appear to be Zhālah’s poems critical of the new regime in Iran, published immediately after her departure in order to distance herself from the laudatory sentiments expressed in some poems in her earlier collection (Agar hizār qalam dāshtam…) and to situate herself more firmly within the milieu of exiled Iranians in the Western diaspora.

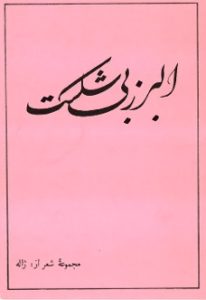

- Alburz-i bī’shikast (The invincible Alborz), London, 1362/1983.28Zhālah Isfahānī, Alburz-i bī’shikast [The invincible Alborz] (self-pub., London, 1362/1983). No publisher is listed, but Zhālah thanks her son Mihrdād for overseeing its publication. The book contains forty-five poems across ninety-one pages, including both previously published and new works. Most are in the Nimaic style, some stanzaic (quatrains); no ghazals are included in this volume. Most convey nationalist or anti-war sentiments, such as the poem written from the perspective of children, “Biguzārīd buzurg shavīm” (Let us grow up!).29Zhālah Isfahānī, Alburz-i bī’shikast [The invincible Alborz] (self-pub., London, 1362/1983), 25.

Figure 10: Cover of the book Alburz-i bī’shikast (The invincible Alborz), London, 1362/1983.

- Har gulī būʾī dārad (Each flower has a different scent), London: Dawrān, 1364/1985.30Zhālah Isfahānī, Har gulī būʾī dārad [Each flower has a different scent] (London: Dawrān, 1364/1985). The book contains verse translations of twelve poems by Russian and Azeri poets, translated during 1346–1356/1967–1977. The translator’s name appears as Sāmān.

- Ay bād-i shurtah (O! Fair wind), London, 1365/1986.31Zhālah Isfahānī, Ay bād-i shurtah [O! Fair wind] (self-pub., London, 1365/1986). Zhālah thanks her sons for collecting and publishing these poems. The volume includes forty-two poems.

- Khurūsh-i khāmūshī (The roaring of silence), Stockholm, Bārān, 1371/1992.32Zhālah Isfahānī, Khurūsh-i khāmūshī [The roaring of silence] (Stockholm: Bārān, 1371/1992). The book is a collection of 284 poems spanning 426 pages (including a preface and index). Zhālah seems to have intended this to be a collection of all the poems she considered worthy of preserving, with examples of poems from different periods and styles, with greater emphasis on later poems in free verse. In her preface, shifting between first- and third-person narration, she adopts a modest, and at times apologetic tone regarding her overtly political poems, which she acknowledges may alienate some readers, yet insists they must be included since they speak to their own audience. In the poem “Bā javānān” (To the young, 1365/1986), she admits fatigue with the coarse nature of her own poems, which, bear the taste of the bitter life of her generation (man az khushūnat-i shiʿram bih tang āmadah’am / … / kih taʿm-i zindigī-i talkh-i nasl-i man dārad).33Zhālah Isfahānī, Khurūsh-i khāmūshī [The roaring of silence] (Stockholm: Bārān, 1371/1992), 83.

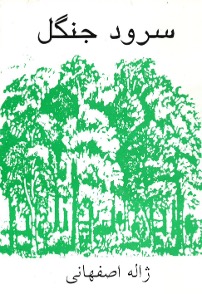

- Surūd-i jangal (The hymn of the forest), London, 1373/1994.34Zhālah Isfahānī, Surūd-i jangal: Surūdah’hā-yi imrūz va dīrūz [The hymn of the forest: Poems of today and yesterday] (self-pub., London, 1373/1994). Subtitled “Poems of today and yesterday” (Surūdah’hā-yi imrūz va dīrūz), the volume contains 154 poems in about 300 pages, including a preface and the text of Zhālah’s 1382/1993 speech on poetry. In her preface, she presents this book as a continuation of—or complement to—Khurūsh-i khāmūshī. She acknowledges that some poems may no longer align with her current tastes, but she seeks to familiarize readers with the breadth of experiences and struggles she endured throughout her life. She also encourages readers to consult the concluding article about poetry to better understand her present view on poetry.

Figure 11 (left): Cover of the book Surūd-i jangal, London, 1373/1994. |

Figure 12 (right): Title page of Surūd-i jangal, featuring Zhālah’s handwriting and signature. |

- Tarannum-i parvāz (The trilling of flight), London, 1375/1996.35Zhālah Isfahānī, Tarannum-i parvāz: Shiʿr’hā va namāyish’nāmah-yi manzūm-i Tīmūr Gūrkān [The trilling of flight: Poems and the verse play of Tīmūr Gūrkān] (self-pub., London, 1375/1996). This is a short volume of fifty-four pages and subtitled Shiʿr’hā va namāyish’nāmah-yi manzūm-i Tīmūr Gūrkān (Poems and the verse play of Tīmūr Gūrkān). In addition to the play, it contains twenty-one poems and eleven brief, haiku-like poems (numbered but not dated), presented under the title Ishārah’hā (Allusions). These suggest Zhālah’s willingness to experiment with different forms, perhaps under the influence of other Iranian poets she met in London.

- Mawj dar mawj (Wave upon wave), Tehran: Alburz, 1376/1997.36Zhālah Isfahānī, Mawj dar mawj: Guzīnah-ʾi shiʿrʹhā [Wave upon wave: Selected poems] (Tehran: Alburz, 1376/1997). Subtitled Selected Poems (Guzīnah-i shiʿr’hā), this collection of about 170 poems was carefully curated to meet the standards of censorship in Iran.

- Sāyah-ʾi sāl’hā (The shadow of years), Essen: Nima Verlag, 1379/2000. This is Zhālah’s autobiography, written in the third person, in which she refers to herself as Mastānah.

- Shukūh-i shikuftan (The majesty of blossoming), Essen: Nima Verlag, 1381/ This is a collection of ninety-nine poems, comprising both new works and selections from earlier publications.

- Majmūʿah-ʾi ashʿār (Collection of poems), Tehran: Nigāh, 1384/2005. Though presented as a collection of poems (with the designation “Volume 1” [Daftar-i avval]), it is a selective compilation of nearly 700 pages. It appears to include all the poems that could be published in Iran under censorship, in some cases with minor alterations.

- Migrating Birds (Parandagān-i muhājir), London: Shiraz, 2006.37Zhālah Isfahānī, Migrating Birds: A selection of poems (London: Shiraz, 2006). A bilingual volume of fifty poems by Zhālah translated into English by Rūhī Shafīʿī, who also provides an introduction.

- Shukūfah’hā-yi zimistānī (Winter blossoms), London, 2007.38Zhālah Isfahānī, Shukūfahʹhā-yi zimistānī [Winter blossoms] (self-pub., London, 2007). These are Zhālah’s last poems, some unfinished, published posthumously.

- Az gulistān-i shiʿr-i āzarī, ed. Āygūn ʿAlīzādah, London: Nīkān, 2022.39Zhālah Isfahānī, Az gulistān-i shiʿr-i āzarī [From the rose garden of Azerbaijani poetry] (London: Nīkān, 2022). This is a collection of Zhālah’s works in Azeri translation.

Zhālah passed away on Āzar 7, 1386/November 29, 2007, less than three years after the death of her husband, Badīʿ Tabrīzī, who had died on Day 18, 1383/January 7, 2005). She was eighty-six years old. She left behind her two sons, Bīzhan and Mihrdād, a substantial body of published and unpublished poetry, a foundation,40Bunyād-i Farhangī-i Zhālah Isfahānī (Jaleh Esfahani Cultural Foundation, JECF), 2007, https://www.jalehesfahani.com/. an award established in her name,41Jāyzah-ʾi shiʿr-i Zhālah Isfahānī (Jaleh Esfahani Poetry Award), starting in 2008, http://bit.ly/3EIeguG. and her legacy of being a relentless pursuer of all people’s aspirations for freedom and equality.

In 2021, on the occasion of her centennial, a new selection of her poems (including some previously unpublished pieces) was published in Iran by Nigāh under the title Khurram ān naghmah (Merry be that song).42Zhālah Isfahānī, Khurram ān naghmah [Merry be that song] (Tehran: Nigāh, 1400/2021).

Zhālah Esfahani Cultural Foundation has established a dedicated website (www.esfahani.com), which serves a valuable resource on Zhālah’s life and works. It includes a list of awards, photo galleries, audio recordings of her readings, interviews, videos, documentaries, letters, articles, and additional archival material.