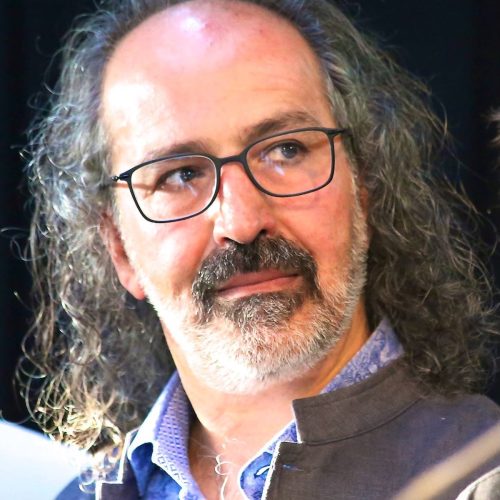

With a University of Toronto General B.A, I was accepted into a three-year M.A. in the newly established (1961) Department of Islamic Studies (now Department of Near & Middle Eastern Civilizations (NMC)). The expanded one-year M.A. included two years of make-up courses in the Islamic Studies undergraduate program. Language proficiency for graduate research was required for graduate study and in addition to the requisite Arabic, I chose Persian and Persian medieval history and culture taught by UK immigrants to the University of Toronto from the British tradition of study of the Middle East, Professors Michael Wickens (Trinity College, Cambridge) and Roger Savory (School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London). Persian was the source language for my thesis on “Religion and Politics Under the First Two Tughluqs, as viewed in the contemporary traditional sources, with special reference to Barani.” (Supervisors: Professor Aziz Ahmad and Professor G. Michael Wickens). Throughout my undergraduate and graduate studies, the focus of the Department of Islamic Studies was the study of medieval Arab, Persian and Turkish history, language, literature, and culture; its program was based on a concept of the medieval Middle East as an entity linked by a common Islamic heritage. I was a Teaching Fellow in the U of T Department of Islamic Studies, an Instructor, a Lecturer, an Assistant Professor and became an Associate Professor in 1978. As a junior appointment, I made the choice to focus my teaching on the modern Middle East and to introduce literature as a source of social history. This was facilitated by an escalating availability of English translations of modern Arabic and Turkish and Persian prose as well as poetry. Literature was a prominent feature of the course syllabi for all the courses I taught such as Middle Eastern Society: Traditional and Modern, Modern Middle Eastern Literatures: A Mirror of Society, Women’s Stories of the Middle East. The students in my courses were curious to learn about a part of the world they were not exposed to in Toronto public or high school curricula or in newspapers and magazines. The influx of Iranian students following the Iranian Revolution of 1979 provided a constituency for courses on Iran and literature in the original Persian. Readings in Modern Persian Literature (in the original Persian) catered to native speakers. The Iranian Short Story in Translation, Iranian Culture and Society in the Twentieth Century, Readings in Modern Persian Literature in Translation were available to the larger undergraduate student population. At the graduate level where Arabic, Turkish and Persian studies became distinct, I offered Literature and Society in 20th c. Iran (in the original Persian), and Persian Literature in the Diaspora. In retirement, I offer a course that I did not previously offer which focuses on the memoirs (originally in Persian and available in English) of Iranian Women: Iranian Women Reveal their Lives: The First Generation.

The theses I supervised reflect the broad academic training I received as a graduate student and were specifically focused on women’s poetry (“Gulten Akin, A Pioneering Turkish Woman Poet: An Analysis of Her Life, Poetry and Poetics Within Their Social, Historical and Literary Context” (defended 2001) and women in their social setting (“The New Armenian Woman’s Writing in the Ottoman Empire, 1880-1915” (defended 2000). I served as a co-supervisor for the thesis of the well-known poet Saeed Ghahremani whose granting department was the U of T Centre for Comparative Literature.

I consider as part of my education and research the three trips I made to Iran in the 1970s: three months travelling throughout Iran (except the south) in 1971, two months during 1974, living with a family in Tehran and attending a language school, and in 1976, a trip to the Royal Ontario Museum archeological site near Kermanshah. All three visits provided an opportunity to enlarge the range of society portrayed in literature.