Tāhirah Saffārzādah’s Tanīn dar diltā and the Avant-Garde Poetry in Persian Literature

Introduction

Tāhirah Saffārzādah (1938–2008) stands as a distinctive and transformative figure in modern Persian literature. Known for her revolutionary and religious poetry, she has often been categorized as a poet of ideology and resistance. Yet her earlier works, particularly those composed prior to the 1979 Revolution, reveal an underexamined poetic voice marked by formal innovation and aesthetic experimentation. Among these early works, her 1969 collection Tanīn dar diltā (Resonance in Delta) offers a compelling case for reevaluating her contributions to Persian avant-garde poetry. This collection, written during or shortly after her time in the United States, reflects an engagement with modernist and postmodernist techniques, and invites reconsideration of her place within the avant-garde tradition of Persian literature.

This article aims to redefine Saffārzādah’s poetic legacy by examining the avant-garde qualities of Tanīn dar diltā. It proposes a framework of four key parameters, attention to language and linguistic deviation, use of concrete and pattern poetry, polyphony, and bold integration of argot, as tools to identify avant-gardism in Persian poetry. Through this lens, the article explores whether Tanīn dar diltā embodies the formal traits and conceptual ethos of avant-garde literature and argues that Saffārzādah, at least in this early phase, belongs among the most progressive poetic voices of her generation.

The article is divided into three main parts. Part 1, titled “Avant-gardism: Background,” surveys the global and local meanings of avant-garde literature, outlining the historical trajectory of modernist and experimental poetry in Iran from Nīmā Yūshīj to the post-revolutionary era. This section establishes the theoretical groundwork and identifies four core parameters of avant-garde poetry in the Persian context. Part 2, titled “Parameters of Avant-gardism in Contemporary Persian Poetry,” elaborates on each of the four proposed parameters in depth. “Attention to Language and Linguistic Deviation” examines the syntactic and grammatical disruptions characteristic of modern and postmodern Persian poetry. “Concrete and Pattern Poetry” analyzes visual and spatial experimentation in poetic form, where layout and structure contribute to meaning. “Polyphony” investigates the multiplicity of voices and perspectives that disrupt monologic narrative structures, creating layered and dialogic texts. Finally, “Bold Integration of Argot “explores the subversive use of colloquial, foreign, and culturally marginal language as a means of challenging linguistic norms and expanding the expressive range of Persian poetry. Part 3, titled “Avant-gardism in Tāhirah Saffārzādah’s Tanīn dar diltā,” applies the proposed framework to an in-depth analysis of her poetry collection. This section demonstrates how Saffārzādah’s work exhibits the avant-garde features—polyphony, concrete and pattern poetry, and the integration of argot—while largely lacking in linguistic deviation. Subsections of this part mirror the four parameters and closely examine key poems such as Safar-i avval, Ghurbat, and Istihālah, offering detailed textual and structural analysis.

The article concludes by asserting that Tanīn dar diltā marks a high point of avant-garde experimentation in Persian poetry, and that Saffārzādah, contrary to common critical perception, should be counted among the modernist innovators of her time. It also suggests that her poetic evolution, away from experimentation toward ideological and religious themes, highlights the historical tensions between aesthetic freedom and political utility in post-revolutionary Iranian literature. This study is the first to establish a theoretical model for identifying avant-gardism in Persian poetry and to apply it to the work of an individual poet. Its significance lies not only in reevaluating Saffārzādah’s place in literary history, but also in proposing a methodology for analyzing avant-garde elements across other works and poets. Future research could explore the international influences on Saffārzādah’s style, particularly the impact of her exposure to Western literary traditions and trace the enduring legacy of Tanīn dar diltā within later movements such as Movement Poetry and Language Poetry in Iran.

- Avant-gardism: Background

An examination of the definitions provided for avant-garde and avant-gardism reveals several key characteristics that are relevant for this research. Avant-garde, a compound term with military origins, originally referred to a small, elite group of highly trained soldiers who moved ahead of the main regiment to scout potential paths and alert others of looming threats. “Henri de Saint-Simon (1760-1825) first applied the term ‘avant-garde’ in the nineteenth century to describe artists who were ahead of their time. ‘Avant-garde art’ refers to art that breaks traditional norms and conventions, offering a new and fresh perspective on the concept of art. Being progressive and experimental in art, to the extent that the product or work is contrary to or outside the current mainstream and comprehensible trend, and cannot be digested, understood, or appreciated by common standards, especially consumer and commercial art, defines avant-gardism from an artistic viewpoint.”1ʿAlīrizā SamīʿĀzar, Awj va ufūl-i mudirnīsm [The rise and fall of modernism] (1st repr. ed., Tehran: Nazar, 1399/2020), 62.

The progressive nature of avant-gardism represents a tendency to challenge accepted societal norms, primarily in the cultural sphere. Some thinkers consider the existential concept of avant-garde as one of the major characteristics of modernism, distinct from postmodernism.2For more information on differences between postmodernism and avant-garde, see Nicolas Heimendinger, “Nicolas Heimendinger, “Avant-gardes and Postmodernism: The Reception of Peter Bürger’s Theory of the Avant-Garde in American Art Criticism,” Biens Symboliques / Symbolic Goods 11 (2022). Many artists in the modern era and present time have associated themselves with progressive movements, ranging from Dadaism to postmodernism, including Language poets.3Andrew Edgar, Peter Sedgwick, Mafāhīm-i bunyādī-i nazariyah′hā-yi farhangī [Cultural theory: the key concepts], trans. Mihrān Muhājir and Muhamad Nabavī (1st repr. ed., Tehran: Āgāh, 1387/ 2008), 31. Generally, avant-garde is meant to be “beyond time”; therefore, it logically follows that people need some time to identify individuals who are supposedly “beyond their time” or intended to be so. During the emergence of most historically influential movements, avant-garde served to oppose the conventional view of art and challenge the dominant artistic theories prevailing in society, particularly in academic circles.

- Parameters of Avant-gardism in Contemporary Persian Poetry

After the European Industrial Revolution and the advent of the modern era, Iran, like many other “Third World” countries, experienced a tendency toward rationalism, progress, and knowledge in science, technology, and politics, along with a desire to discard superstition. However, Iranian society was neither industrialized like developed European countries, nor did traditionalists show any flexibility toward modernity. Consequently, a group of intellectuals decided to strike a compromise between tradition and modernity to avoid falling behind modern civilization while preserving traditions. As a result, the society, followed by literature and poetry, did not fully experience modernity, as accepting it necessitated complete release from all traditional and ancient restrictions.

Experts emphasize that development must be all-inclusive. If a society progresses only economically without cultural growth, or if some elements of society advance while others lag behind, that society will face crisis. For poetry to undergo genuine modernization, all elements must change harmoniously to prevent it from becoming a verbal caricature.4Kāvūs Hasanlī, Gūnah′hā-yi nawāvarī dar shiʿr-i muʿāsir-i Īrān [Types of innovations in contemporary Iranian poetry] (5th repr. ed., Tehran: Sālis, 1398/2019), 16.

Persian Poetry underwent a shift toward modernism with Nīmā Yūshīj, embracing it later in the 1960s and 1970s. By the 1980s, and 1990s, Persian poetry evolved beyond postmodernism, exploring new artistic territories. After Nīmā Yūshīj, many poets claimed to be progressive and avant-garde, each expanding some aspect of contemporary Persian poetry. Modernist poets exerted their utmost effort to transform Persian poetry.

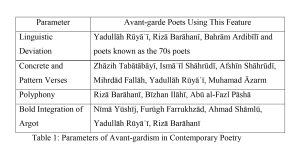

Despite all these considerations, the fundamental issue remains that no source or research has provided specific criteria or parameters for identifying avant-gardism in Persian poetry. Therefore, it is essential to first establish clear parameters for identifying avant-gardism in Persian poetry before examining whether Saffārzādah’s work exhibits avant-garde characteristics and ultimately determining whether she can be considered one of the avant-garde poets in Persian literature. I propose that the following four parameters serve as indicators of avant-garde poetry, or the “progressiveness” of a poet. These parameters are based on definitions of avant-garde in relation to the evolution of Persian poetry over the past century, with a specific focus on poets who are unquestionably avant-garde.5To define such parameters, the poetry and literary theories of influential and dissenting poets of the recent one hundred years are analyzed. The most important poets in this study are Nīmā Yūshīj, Shams al-Dīn Tundar Kiyā, Furūgh Farrukhzād, Hūshang Īrānī, Zhāzih Tabātabāyī, Ahmad Shāmlū, Ahmad Rizā Ahmadī, Bīzhan Ilahī, Yadullāh Rawyāyī, Sayyīd ʿAlī Sālihī, Rizā Barāhanī, Abū al-Fazl Pāshā, Mihrdād Fallāh, ʿAlī Bābāchāhī, Muhammad Āzarm, Ānīmā Ihtiyāt and Afshīn Shāhrūdī. Manifestos in connection with forms such as Nīmāʾī poetry (Nīmā Yūshīj’s introductions to Ismaʿīl Shāhrudī’s books Ākharīn nabard [The last war] and Harf′hā-yi hamsāyah [Neighbor says], Hajm-girāyī [Spacementalism] (Manifesto of Spacementalism), Shiʿr-i zabānī [Language poetry], (Epilogue to Rizā Barāhani’s Khitāb bih parvānah′hā [Addressed to butterflies]), Shiʿr-i Harakat [Movement poetry], (Abū al-Fazl Pāshā’s Harakat va Shiʿr [Movement and poetry], Shiʿr-i dīdārī [Concrete verse], (Afshīn Shāhrūdī’s introduction to his book, Afshīnhā-yi Shāhrūdī), Shiʿr-i farā-Nīmāʾī [Post-Nīmāʾī poetry] (Epilogue to ʿAlī Bābāchāhī’s ʿAql ʿazābam mī-dihad [Wisdom bothers me] have all been carefully considered and four avant-garde parameters were selected to discuss the works of these poets. The parameters to be considered are: a. Attention to Language and Linguistic Deviation, b. Concrete and Pattern Poetry, c. Polyphony, and d. Boldness in the Integration of Argot.

- Attention to Language and Linguistic Deviation

From the time Nīmā Yūshīj initiated his monumental work in Persian poetry to the present day, one of the preoccupations of poets has been engaging with the essence of language and its syntactic and grammatical operations. This began with Nīmā Yūshīj’s cautious linguistic deviations and those of his students, evolved into more radical forms in the poetry of Hūshang Īrānī and Shams al-Dīn Tundar Kiyā, and later became a definitive characteristic of poetical movements exemplified by poets such as Yadullāh Rūyāyī, Rizā Barāhanī, and poets of the 1370s/1990s. Tendencies such as shiʿr-i hajm (volume poetry), zabāniyat (linguisticality), shiʿr-i harakat (movement poetry), shiʿr-i mutafāvit (différance poetry) all share this common feature. Today, poetry that lacks linguistic deviation and norm-creating linguistic behaviors falls outside the definition of poetry. Consequently, attention to language and its syntactic, grammatical, and linguistic deviations is a prominent feature in the work of all influential poets, and it can be regarded as the first parameter in determining the avant-garde poetry.

- Concrete and Pattern Poetry

The focus on the pattern of poetry and the written form of words has been a focus of some poets in Persian literature since 1330s and 1340s/1950s and 1960s. Ismāʿīl Shāhrūdī, Kiyūmars Munshī-zādah, Hushang Īrānī and others presented examples, albeit few, of this mental preoccupation in their poetry, which became known as concrete and pattern poetry. This type of poetry can be first seen in a professional and cohesive way, entirely focused on concrete poetry, in two collections of poetry: Ajaq vajaq (Gaudy)] and Ablaq (Piebald) by Zhāzih Tabātābayī in 1350s/1970s. Later, in the 1380s and 1390s/2000s and 2010s, it was introduced as a concrete poetry movement in the works of poets such as Afshīn Shāhrūdī, Mihrdād Fallāh and Ānīmā Ihtiyāt.

According to Laylā Sādiqī, “Concrete verse is a type of poetry that is produced and understood by receiving verbal and visual data (pattern) through verbal and visual channels. These data are combined in the brain to form meaning as a unified verbal-visual text. The importance of the pattern stems from the fact that humans have never experienced the world around them without images, and many of their lived experiences would seem almost impossible without the presence of images.”6Laylā Sādiqī, “Shiʿr-i tasvīrī va shiʿr-i dīdārī” [Pattern poetry and concrete poetry], Majalah-i Īntirnitī Āvāngārd′hā [The Avangard online magazine], (1395/2016).

Concrete poetry (shiʿr-i dīdārī) is a newer and more developed form of pattern poetry (shiʿr-i tasvīrī). Poets of concrete poetry craft their poems by using graphics and manipulating words and letters in a way that creates a visual pattern for the viewer. Understanding the poet’s message is made possible by looking at the graphic appearance of the poem.7Hasan Anūshah, Farhangnāmah-ʾi adabī-i Fārsī (Dānishnāmah-ʾi adab-i Fārsī) [Dictionary of Persian literature], (Tehran: Sāzmān-i chāp va intishārāt-i vizārat-i farhang va irshād-i Islāmī, 1376/1997), 2:897. In another definition, pattern poetry, also known as picture poetry or painted poetry, is described as a form of poetry in which the external structure mirrors the shape of an object, corresponding to a concept within the poem. The structure conveys meaning or emotion to the reader. In this type of poetry, the arrangement of phonetic and lexical elements, along with the placement of hemstitches, creates an image that is directly linked to the poem’s content or imagery. The key difference between pattern poetry and concrete poetry is that pattern poetry is “auditory-visual,” while concrete poetry is “written-visual.” Therefore, this new feature of poetry, its attention to both visual and written aspects, can be considered one of the hallmarks of progressive and avant-garde poets.

- Polyphony

The pluralist view is one of the fundamental components of postmodernism. “If postmodernism has one key idea, it is pluralism. Put simply, pluralism is preferring several (many) to one…. The philosophy of pluralism accepts more than one principle. Text is not the container of a single deep meaning; it is a place for plural readings.”8HusaynʿAlī Nawzarī, Sūratbandī-yi mudirnītih va pustmudirnītih [Configuration of modernism and postmodernism] (Tehran: Naqsh-i jahān, 1385/2006), 280. The influence of the pluralist view of postmodernism is also evident in making poetry polyphonic; it is no longer a poem told by a single poet, but rather a space where different sounds, rhythms, syntactical and grammatical logics, contradictions, and contrasts coexist. As a result, the poet’s voice, (traditionally perceived) as a “soliloquist,” is overwhelmed by multiple voices. “Polyphonic poetry eliminates the autocracy of voice, the tyranny of rhythm, and takes away the subject, verb and object of the autocratic sentence. Polyphonic poetry removes the autocracy of finding one meaning as the sole meaning of the word, sinking the poem into an endless process of interpretation and presenting different voices.”9Rizā Barāhanī, Khitāb bih parvānah′hā [Addressed to butterflies] (Tehran: Nashr-i Markaz, 1388/2009), 1.

In Persian literature, polyphonic poetry, shaped by postmodernist views, became prominent in the 1370s/1990s, first appearing consistently and systematically in Rizā Barāhanī’s Khitāb bih parvānah′hā (Address to butterflies). The works such as Nigāhī charkhān (Rotating look), Haft (Seven), Khitāb bih parvānah′h (Address to butterflies), Mī-sūzīm (We burn), and others, with their, frequent temporal disruptions, repeated narrative interruptions, and the narrator assuming multiple distinct characters, create a polyphonic atmosphere.

As I always sweep my hair from my eyebrows,

You are sitting there,

On the leaves and in Darakeh, and the wind blows, and snow falls, and I am not me.

Every day, I bought a spray of flowers from Amirabad flower shop

Only one spray.

-But such eyes, as if a pair of dates-10Barāhanī, Khitāb bih parvānah’hā, 78.

Fundamentally, polyphony is one the essential features of Language Poetry, which Barāhanī endeavored to develop. Later, his students such as Hūshyār Ansārīfard, Shams Āqā Jānī, Farkhundah Hājīzādah, Rawyā Taftī, and others, implemented this concept in their poetry, presented as the Language Poetry Movement.

- Bold Integration of Argot

Argot is one of the key terms in the poetic discourse of Nīmā Yūshīj, regarded as the most avant-garde poet in contemporary Persian literature. In his poetic discourse, argot or “argot language” often appears alongside archaic language. He frequently employs this term in his book Harf′hā-yi hamsāyah (The neighbor says), which contains his theories and views on poetry.11ʿAlīrizā Raʿiyyat Hasanābādī, “Ārgū dar guftmān-i adabī-yi Nīmā Yūshīj” [Argot in Nīmā Yūshīj’s literary discourse], Adabiyāt-i Pārsī-i Muʿāsir 10, no. 28 (Murdād 1399/August 2020): 155-73. Nīmā Yūshīj calls upon his readers to investigate argot and considers one of the main tasks of the audience to be the exploration of both archaic and argotic elements. Undoubtedly, his intention with this investigation and exploration is not merely to search for colloquial words. Rather, his purpose is to examine linguistic structures, syntactical deviations, the formation of word combinations, and other linguistic parameters in such a way that this investigation leads to the discovery of formulae and rules that would transform the language of poetry, like other argots, into a specific, unique argot. This concept implies the hidden nature of argot, and the investigation into argot also entails exploring the hidden languages of the time.12Hasanābādī, “Ārgū dar guftmān-i adabī-i Nīmā Yūshīj,” 155-73.

These statements essentially convey that, firstly, the exploration of existing argots (in the sense of vernacular, local languages, and secret languages) and, secondly, the construction of a new argot in poetry were key components of Nīmā Yūshīj’s vision for poetic reform. This principle has been followed in the works of other avant-garde and progressive poets such as Furūgh Farrukhzād, Yadullāh Rūyāʾī, Rizā Barāhanī, and others. Therefore, the boldness of the poets in using argot and employing it correctly and poetically can be considered another parameter of avant-gardism.

- Avant-gardism in Tāhirah Saffārzādah’s Tanīn dar diltā

Having proposed some defining features and parameters of avant-gardism in Persian poetry, this section will examine their manifestation in Tāhirah Saffārzādah’s Tanīn dar diltā. Saffārzādah, renowned not only for her revolutionary and ideological poetry but also for her religious verses and pioneering role in modern religious poetry, stands as a significant figure in the resistance poetry movement. Her fame extends beyond her poetic works to her English translation of the Qurʾān. In her later works, the Qurʾān and Shiʿi Imams become central themes. Her poetry, which addresses serious political and social issues, has been warmly received by political and religious power institutions. This recognition is evident in her selection for the first Fajr poetry festival and her bestowal of the title of “Khādim al-Qurʾān” (Servant of the Qurʾān).

Historically and stylistically, Tāhirah Saffārzādah’s poetry can be categorized into two periods: “pre-1979 Revolution poetry” and “post-1979 Revolution poetry.” In the pre-Revolution works, there are clear signs of a poet who is transformative, norm-defying, and norm-creating.13Saffārzādah’s pre-revolution poetry can also be divided into the period before her trip to the US and the period after the trip, because the form and content of poetry from these two periods are distinct. The classification into pre- and post-revolution is useful because Saffārzādah’s post-revolution poetry is devoid of avant-gardism, and she can be considered a progressive and avant-garde poet only based on Tanīn dar diltā. However, these qualities in her poetry have largely been overshadowed by her fame as a religious and revolutionary poet. Her poetry in this period is distinctly different from her later works. Notable features in her early works, especially in the collection Tanīn dar diltā, include a focus on form and structure, language, and pattern and concrete verses. These poems represent some “of the most successful examples of Saffārzādah’s work, as they not only embody strong ideas but also retain poetic essence. In fact, it was during this period that Saffārzādah’s brilliance first established her as one of the prominent contemporary poets.”14Ahmad Khalīlī, Rizā Sattārī and Muhsin Mahdīniyā, “Naqd-i shiʿr-i Tāhirah Saffārzādah” [Criticism of Tāhirah Saffārzādah’s poetry], Tārikh-i Adabiyyāt, no. 72 (1391/2012): 110. Some critics, however, argue that her poetry during this time was somewhat influenced by Western literary theories and her works reflect a certain theoretical tendency, which could be considered an unconscious result of her exposure to foreign language and literature. At any rate, Saffārzādah published three collections of poetry during this period: Tanīn dar diltā (poems from 1347–49/1968–70), Sadd va bāzuvān (The dam and arms) (poetry from 1345–48/1966–69) and Safar-i panjum (The fifth voyage, poems from 1351–55/1972–76). Our discussion will focus on Tanīn dar diltā

Tanīn dar diltā is Saffārzādah’s third collection of poems, published in 1349/1969 in Tehran. The 1340s/1960s stand as a pivotal decade for Persian avant-garde poetry. In 1340/1960, Ahmad Rizā Ahmadī’s book Tarh (Sketch) was published, and the “New Wave” (mawj-i naw) movement was introduced to literary circles. This movement solidified with the release of Ahmadī’s subsequent collections Rūznāmah-yi shīshah-yī (The Glass newspaper) (1343/1964) and Vaqt-i khūb-i masāʾīb (Good time of miseries) (1347/1968). In the mid-1969s, poets affiliated with the shiʿr-i dīgar (another poetry) movement emerged. These poets included Bīzhan Ilāhī, Bahrām Ardabīlī, and Parvīz Islāmpūr. At the same time, some of the most significant collections of established poets, such as Ahmad Shāmlū, Suhrāb Sipihrī, and Furūgh Farrūkhzād, were published during this period. Toward the decade’s end, the manifesto of spacementalism (hajm-girāyī), signed by a group of poets and artists, was released in 1348/1969. This text remains profoundly influential in Persian poetry.

Theoretical works also flourished in this decade. Notably, Ismāʿīl Nūr ʿĀlā’s Suvar va asbāb dar shiʿr-i imrūz-i Īrān (Image and technique in modern Iranian poetry), published in 1346/1968, offered vigorous critiques of collections published during this decade. Tanīn dar diltā was published in a dynamic literary atmosphere characterized by experimentation and theoretical debates. Given the intellectually charged environment of Persian poetry in the 1960s, a work garnering critical attention would necessarily possess exceptional qualities. In the following paragraphs, I will analyze selected poems from Tanīn dar diltā, focusing on the four avant-garde parameters outlined in the previous section, and demonstrate that the collection embodies features of avant-garde poetry.

- Polyphony

Tanīn dar diltā is significant in several ways, exhibiting key features of avant-gardism. Notably, nearly three decades before the introduction of Language Movement and discussions on polyphony within contemporary Persian poetry, clear indications of these elements can already be found in Tanīn dar diltā. To illustrate this, I will analyze the first poem of this collection, Safar-i avval (The first voyage).

Safar-i avval consists of twenty-five interconnected yet distinct episodes and pieces. This poem can be seen as “a collection of associations based on symmetry and contrast, often with satirical undertones, created while observing a horrific scene (from the perspective of the poet encountering it for the first time). Each association leads to another, and the interaction and combination of all these associations form the final structure of the poem, a labyrinthine arrangement with concentric circles, at the center of which a corpse is being cremated in India. The first circle represents India (the primary setting of the poem), the second circle represents the poet’s homeland, and the third represents America, where the poet has spent some time. Each circle encompasses all the others. The poem’s general atmosphere and movement are associated with circular paths; wherever it departs from India, it eventually returns there.”15Muhamad Huqūqī, Shiʿr-i naw as āghāz tā imrūz, 1301-1307 [New poetry from beginning till now 1301-1370/1922-1991], (Tehran: Sālis, 1377 /1998), 2:1018.

In this poem, three distinct and independent voices emerge from three characters, appearing in various episodes. The first voice belongs to the narrator or poet, presenting a narrative from three separate geographical points or circles. The second voice belongs to someone conversing with an interlocutor from India, while the third voice is that of Sharat, who responds with a single word, “āchā” (alright). The poem presents a threefold polyphony and except for Sharat, who answers with the Indian expression “āchā,” the other two voices are entirely distinct. One voice consistently expresses political concerns, while the other shifts through different time periods, engaging with memories and everyday occurrences. The polyphonic atmosphere in the poem emerges from the blending of different time zones, the interruption of narration with frequent interventions, and the narrator’s presence as multiple separate characters. The breakdown of linear narration is facilitated by this polyphonic environment, which Saffārzādah introduces in an initial form. This technique would later be perfected in the 1990s in Khitāb bih parvānah′hā (Address to butterflies).

In “Safar-i avval,” Saffārzādah portrays death in India, Iran, and America through mental associations, touching on various themes such as servitude and poverty in India, worldwide tyranny and turmoil, and her own childhood. The poem’s length enables her to weave all these concepts into her poetry; nothing appears superfluous, and the harmony between word and mental associations is carefully maintained. Moreover, the intertextual relationships between the different episodes lend the poem a unique, interwoven structure, resulting in a polyphonic rather than a mono-semantic piece.

The following explains the relationships between the twenty-five different episodes. A noteworthy point is that the episodes in which Sharat speaks are meaningful on their own; when these episodes are arranged together, they form an independent poem with its own narrative, form, and structure. Episodes in which Sharat and his interlocutor converse are as follows (E stands for episode):

E1, E3, E5, E7, E10, E13, E19, E20, E24, E25

Beyond the apparent intertextual connections between the episodes, there are numerous hidden poetic intertextual relations within the poem, which were unique at the time of its composition. For example, in episode 20, the word “āchā” and the phrase “three unemployed” on a Monday are repeated three times, establishing an intertextual relationship with episode 21 through the phrase “three spinsters in three floral dresses with three big noses in one line,” and further connecting with episode 23 through the triple repetition of “two flowers.” This intertextual relationship is formed not only through the numbers three and two, but also through the repeated phrases: “two flowers,” “three unemployed,” and Monday.16Tāhirah Saffārzādah, Tanīn dar diltā [Resonance in delta] (2nd rep., ed., Shiraz: Navīd, 1365/1987), 29-32.

The same pattern of form, semantic association, and the creation of a polyphonic atmosphere appears in another poem, “Safar-i Zamzam” (Zamzam voyage), which portrays a mental journey. Zamzam voyage describes the poet’s trip to Imāmzādah Dāvūd on a mule that constantly veers toward the edge of the valley. For the poet, this journey is associated with the journey to Mecca, toward the Zamzam well. Zamzam reminds the poet of a dry and oil producing island devoid of greenery, in contrast to a harbor swamp where a man lives with his wife and child! Thus, from the perspective of creating a polyphonic and multi-voiced atmosphere, Tanīn dar diltā can be regarded as avant-garde.

- Concrete and Pattern Poetry

As mentioned earlier, concrete and pattern verses were seriously explored in Zhāzih Tabātābayī’s collections in the mid-1950s/1970s. However, seven years earlier, six distinct poems in Tanīn dar diltā already exibited all the characteristics of concrete and pattern poetry.

The first poem entitled Ghurbat (homesickness/exile/loneliness in a foreign land) is presented as:17Saffārzādah, Tanīn dar diltā, 55.

Firstly, this poem is not a concrete poem but rather a pattern one, as the text and words carry meaning on their own: “Here everyone asks me: where do you come from?” However, the visual image of the poem aids in understanding and creating multiple meanings. The form of writing evokes several images: a crucified figure, a person standing with open arms, and the four cardinal directions with north, east, and west positioned above and south below. Various meanings related to ghurbat (homesickness/exile/loneliness in a foreign land) can be derived from these three visual patterns. The crucified figure may symbolize the sorrow and hardships of ghurbat. The person with open arms represents the kind and welcoming behavior of the host country’s people, offering another aspect of life in a foreign land. The concept of freedom from place, the notion “where,” and the feeling of being without a homeland are additional meanings that arise from considering the four cardinal directions, closely tied to human nostalgia.

Firstly, this poem is not a concrete poem but rather a pattern one, as the text and words carry meaning on their own: “Here everyone asks me: where do you come from?” However, the visual image of the poem aids in understanding and creating multiple meanings. The form of writing evokes several images: a crucified figure, a person standing with open arms, and the four cardinal directions with north, east, and west positioned above and south below. Various meanings related to ghurbat (homesickness/exile/loneliness in a foreign land) can be derived from these three visual patterns. The crucified figure may symbolize the sorrow and hardships of ghurbat. The person with open arms represents the kind and welcoming behavior of the host country’s people, offering another aspect of life in a foreign land. The concept of freedom from place, the notion “where,” and the feeling of being without a homeland are additional meanings that arise from considering the four cardinal directions, closely tied to human nostalgia.

The second poem, titled Istihālah (Transformation), holds more significance than the other five poems in this collection. Its importance lies in being a concrete poem rather than a pattern poem, and it is composed of two simple words, ū (he) and mā (we). Without seeing the poem, its meaning cannot be grasped, as understanding the poem relies on its visual structure. The visual arrangement shows the words “he” and “we,” descending in the same line, then diverging at a fork, each diverging in a different direction. The transformation in this poem is the shifting identity of “he” and “we” and their separation. Many concepts can be drawn from this visual form, the most immediate being the separation of humans from God (He), the change in identity following this separation, and the existential transformation of humans from the world of meaning.

In addition to this concrete feature, this poem serves as a clear example of shiʿr-i harakat (Movement poetry), a style based on transformation that emerged in the 1370s/1990s. In other words, Tanīn dar diltā offers a clear and prominent example of the theory that would later develop in the 1370s/1990s. To further explore this aspect, it is necessary to examine shiʿr-i harakat, one of the poetry forms (movements) of the 1370s/1990s, first introduced with the publication of a theoretical text by Abū al-Fazl Pāshā:

The article Harakat va shiʿr was written in 1373/1994 and published in the literary section “Hear from the reed” of Itilāʿāt newspaper on 14, 21, 28 Isfand, 1375/March 4, 11, 18, 1997. Due to frequent reader requests, it was reprinted twice: first, in Miʿyār magazine, issue no. 22 (Bahman 1376/January 1998) and no. 23 (Urdībihisht 1377/April 1998), and second, in Asr-i Panjshanbih, the literary issue of ʿAsr newspaper (Shiraz), issues no. 36-28 (Farvardin 20, 27 and 3 Urdībihisht 1377).18Abū al-Fazl Pāshā, Harakat va shiʿr [Movement and poetry] (Tehran: Rūzgār 1379/2000), 7.

Years later, after consultation with poets and critics, Pāshā revised and edited the article and published the book Harakat va shʿir in 1379/2000. This book included theoretical views on Movement poetry, along with examples from poets associated with this movement. One of the key features of Movement poetry, discussed in detail in the book, is the “transformation of the building blocks of poetry.” The “central core of poetry is movement,”19Abū al-Fazl Pāshā, “Shiʿr-i Harakat, shiʿr-i istihālah” (Interview with Abū al-Fazl Pāshā), Āzmā, no. 12 (1379/2000): 40-43. which is so essential that a poem lacking transformation cannot be considered part of Movement poetry, even if it exhibits other external features of Movement poetry and the poetry of the 1370s/1990s. As Pāshā writes,

In Movement poetry, one of the building blocks of the poem has a specific state that either accepts or is affected by certain situations, which can be called harakat (movement). This building block then leads to transformation (istihālah), becoming something else. The poem itself is constructed through such an arrangement. In other words, all of this takes place within the structure of the poem. For example, if a building block, such as a character, initiates the movement of the poem, the characters will influence each other, and one may transform into another by the end of the poem. This interaction results in the gradual formation of the poem’s structure, culminating in the transformation of that building block. Therefore, I must emphasize the phrase “building block in structure” and assert that the essence of movement (harakat) or the transformation within a poem relies on the building block in the poem’s structure. These building blocks can be an image in one harakat poem, a character in another, or even time and place simultaneously in yet another poem.20Pāshā, Harakat va shiʿr, 97.

The above explanation is clear, and the only additional point that can complement it is the distinction between “change and replacement of elements of poetry” and “transformation”:

The mere deletion, alteration, or relocation of building blocks cannot be considered transformation, as the foundation of Movement poetry is transformation not deletion, alteration, or relocation. In other words, a poem that only deletes, changes, or relocates elements cannot be said to have a complete structure. For example, if an image is replaced by another in a poem without any arrangement or reorganization, this is merely deletion or change, not transformation.21Pāshā, Harakat va shiʿr, 98.

The poem Istihālah (Transformaion) in Tanīn dar diltā not only carries the title Istihalah, but Saffārzādah has also placed the title on the previous page for emphasis. This poem exemplifies the characteristics of istihālah (transformation) in Movement poetry, displaying simultaneous movement in one of the poem’s building blocks. Two poetic elements, “he” and “we,” move alongside each other; however, at some point, their movements separate, transforming them into two distinct and independent elements.22Saffārzādah, Tanīn dar diltā, 59. This transformation is a key feature in many poems of Movement poetry, categorized as break-and-link istihālah (transformation).23ʿAlīrizā Raʿiyyat Hasanābādī, “Hajm-girāī va qudrat, tahlīl-i naqsh-i nahād′hā-yi qudrat dar hayāt-i tārīkhī-yi bayāniyahʾ-i shiʿr-i hajm [Spacementalim and power, an analysis of the role of power institutions in the historical life of manifesto of spacementalism (Isfahān: Khāmūsh, 1399/2020), 114.

It is unclear whether the poets of Movement poetry, and Abū al-Fazl Pāshā were directly inspired by this poem. However, since the title of the poem is istihālah, and the title of Saffārzādah’s other book is Harakat va dīrūz (Movement and yesterday), while the original theorist of Movement poetry, Pāshā, titled his book Harakat va shiʿr (Movement and poetry), one may infer that the idea of Movement theory was borrowed from Saffārzādah. Regardless of whether the idea was borrowed or not, this poem is recognized as an example of Movement poetry. Interestingly, Pāshā himself claimed in his book that he had found examples of Movement poetry in the works of poets such as Shāmlū, and his theory of Movement poetry was the result of compiling these examples.

We can analyze the other poems in this section in the same way by examining the relationship between the poem and its pattern and uncover links. In addition, in Episode 3 of the poem Safar-i avval, Saffārzādah integrates the visual pattern with textual representations (of an elevator or stairs moving up and down) which can also be classified within this category.

We can analyze the other poems in this section in the same way by examining the relationship between the poem and its pattern and uncover links. In addition, in Episode 3 of the poem Safar-i avval, Saffārzādah integrates the visual pattern with textual representations (of an elevator or stairs moving up and down) which can also be classified within this category.

Smoke

Two steps at a time

Climbs up

The elevator on the second floor has stopped working at night

Life is the repetition of the elevator’s gaze

Up

Down

Down

Up

Down

Down

Up

Down

-This dead had confessed to the Brahmins24Saffārzādah, Tanīn dar diltā, 11.

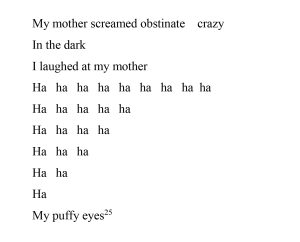

In the third section of the poem Nahang′hā bā man mihrbān būdand (Whales are kind to me), the image of laughter is presented visually:25Saffārzādah, Tanīn dar Diltā, 81.  The following table is detailed information about the six poems that Saffārzādah referred to as concrete.

The following table is detailed information about the six poems that Saffārzādah referred to as concrete.

Thus, Tanīn dar diltā can be considered an avant-garde and progressive poem from the perspective of concrete and pattern poetry.

Thus, Tanīn dar diltā can be considered an avant-garde and progressive poem from the perspective of concrete and pattern poetry.

- Bold Integration of Argot

Tanīn dar diltā is notable for its extensive use of foreign and non-Persian names (of individuals and places) and terms. For example, in the poem Safar-i avval, which depicts the cremation of corpses in India, the reader encounters Indian terms, and names appear, including Benares, Kolkata, Acha, Maharaja, Bombay, Brahmin, Tah Mahal, Rama, and Sharat. Elsewhere in the same poem, through associative recollection of other poetic landscapes, European and American names of individuals and places appear, including Oppenheimer, Prague, Ashbury, California, Sai Chai, Franco, Peron, Williams, New York, Porto Rico, Mrs. Harms, Lancashire, Curzon, UK, Chris, Alfred Hitchcock, George Wallace, Claude, Harlem, Shanka, Smirnov, Alba, Buch, Lindow, Alfredo, George, de Gaulle, Eddie, Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal, Gabriel, Buenos Aires, Irova, Carlos, Payton, John, Mayakovski, Yevtushenko, Marx, and Earl’s Court.

At the time of Tanīn dar diltā’s publication, the use of such foreign words in Persian poetry was rare. However, their frequency in this collection is so pronounced that it constitutes a defining a stylistic feature of Tāhirah Saffārzādah’s poetry. Yet what is the significance of merely incorporating foreign words related to Eastern and Western cultures? Saffārzādah clarifies her approach:

This was not intentional but necessary. While I belong to the East, an easterner must also expose herself to global cultures and events. Safar-i avval and Safar-i Zamzam, with their foreign vocabulary, reflect the perspective an easterner observing the world beyond her homeland, the world she has seen, known, and evaluated for its divergent and shared characteristics. I cannot transform the Indian Sharat, German Lindow, and the French de Gaulle into Shāpūr, Parvīz, and Dāryūsh. They exist in their own names, as do their cultures and cities.26ʿAli Muhamad Rafīʿī, Bīdārgarī dar ʿilm va hunar (Shinākhtnamahʾ-i Tāhirah Saffārzādah) [Awakening in science and art (Chrestomathy of Tāhirah Saffārzādah)] (Tehran: Hunar-i bīdārī, 1386/2007), 260.

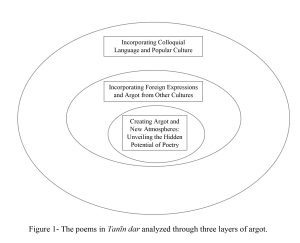

Re-examining the semantic implications of argot, Saffārzādah has introduced elements into Persian literature that were previously “hidden.” Much like the colloquial expressions of Nīmā Yūshīj’s time, incorporating such language into poetry was seen as taboo breaking. However, Saffārzādah goes further by artfully embedding signs and symbols of non-Iranian cultures into her poetry, which align closely with the notion of argot. While Nīmā Yūshīj focused on Iranian and local argot, Saffārzādah thoughtfully incorporates the argot of other cultures, creating a new and progressive argot in Tanīn dar diltā, which stands as a bold example of avant-garde innovation. Furthermore, by using the language of everyday people, Saffārzādah has influenced various aspects of literary language. Her use of colloquial language and common vocabulary renders her writing simple and intimate, establishing a deep connection with the reader’s emotions. At times, she employs colloquial words and phrases, occasionally with a touch of sarcasm, arranging them in a unique, artistic manner that reflects the distinctive architecture of her mind. This approach expands the scope of her vocabulary, featuring words like “lollipops,” “edge of the roof,” “dame,” “hand-picked,” “making excuses,” “panting,” “toolshed,” “hat,” “sunglasses,” “three toman one-way fare.” The poems of Tanīn dar diltā (except for the six concrete poems) can be analyzed through the following layers of argot:

The uppermost layer represents elements adopted by many poets from Nīmā Yūshīj’s theories, incorporating words, slang, and colloquial language from various regions of the country into their poetry. The second layer is unique to Saffārzādah’s poetry, which introduced this broad scope for the first time. The third layer emerges from the interaction of the first two, creating a new argot atmosphere that brings fresh vitality to the poems. These three layers are present throughout the poems discussed, and the poet’s boldness in creating such an atmosphere is worthy of note. Table 3 offers further details on the poems in Tanīn dar diltā regarding avant-garde parameters and characteristics.

The uppermost layer represents elements adopted by many poets from Nīmā Yūshīj’s theories, incorporating words, slang, and colloquial language from various regions of the country into their poetry. The second layer is unique to Saffārzādah’s poetry, which introduced this broad scope for the first time. The third layer emerges from the interaction of the first two, creating a new argot atmosphere that brings fresh vitality to the poems. These three layers are present throughout the poems discussed, and the poet’s boldness in creating such an atmosphere is worthy of note. Table 3 offers further details on the poems in Tanīn dar diltā regarding avant-garde parameters and characteristics.

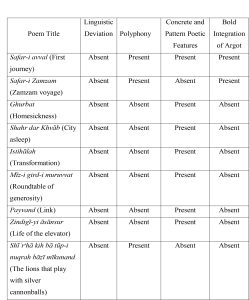

Of the eighteen poems analyzed in this article, two exhibit syntactic and linguistic deviations, while sixteen do not. Eight poems demonstrate polyphony, while ten do not. Nine poems are categorized as concrete-pattern verses, with remaining nine lacking this characteristic. Eight poems feature a notable, bold integration of argot, while ten do not.

Of the eighteen poems analyzed in this article, two exhibit syntactic and linguistic deviations, while sixteen do not. Eight poems demonstrate polyphony, while ten do not. Nine poems are categorized as concrete-pattern verses, with remaining nine lacking this characteristic. Eight poems feature a notable, bold integration of argot, while ten do not.

- Conclusion

According to the established definitions of avant-gardism, the poems from Tāhirah Saffārzādah’s first creative phase exhibit three of the four hallmark features of avant-garde poetry: polyphonic atmosphere, use of concrete-pattern poetry, and bold integration of argot. However, Saffārzādah’s poetry largely lacks the fourth criterion, syntactic and linguistic deviation, except for Istiʿfā, which demonstrates syntactic disruptions across syntagmatic and paradigmatic axes. The remaining poems in Tanīn dar diltā show no linguistic innovation, normalization, or subversion of syntactic structures. Despite this, Saffārzādah’s integration of the three mentioned avant-garde characteristics position her as a pioneering figure within her historical context. Notably, two poems in the collection, titled Tulūʿ (Sunrise) and Girdbād (Whirlwind), lack any avant-garde attributes and remain conventional, stylistically inert works. Based on the cumulative data from prior analyses (Tables 1-3), Saffārzādah’s name in Tanīn dar diltā merits inclusion alongside avant-garde Persian poets such as Nīmā Yūshīj, Ahmad Shāmlū, Yadullāh Rūyāyī, Rizā Barāhanī, Zhāzih Tabātabāyī and Furūgh Farrukhzād.

These groundbreaking features were eclipsed in Saffārzādah’s second creative phases by ideological and religious influences, rendering her poetry incomparable to her earlier avant-garde achievements. During this later period, Saffārzādah regressed into stylistic conventionality, becoming an ordinary poet with marginal voice within contemporary poetic discourse.

Research Recommendations

A: Based on the preceding analysis, Saffārzādah can be regarded as an avant-garde, progressive, and influential poet during a particular phase of her artistic and literary career, specifically during the creation of Tanīn dar diltā. However, several questions emerge in this context. For example, where did her distinctive, adventurous perspective in this collection originate, and what was the source of the remarkable innovation she demonstrated upon her return from the United States? It is therefore recommended that researchers investigate the influence of her trip to the United States on Saffārzādah’s poetic vision.

B: This study has focused exclusively on Tanīn dar diltā, but there is potential for further exploration into the broader development of avant-gardism within the context of Tanīn and its impact on movements such as Movement Poetry, Linguistic Poetry, Concrete and Pattern Poetry, Différance Poetry. Researchers are encouraged to apply the avant-garde parameters outlined in this study to Saffārzādah’s other works, tracking and analyzing the evolution of avant-garde elements from Tanīn to contemporary Iranian poetry.