Shams Jahān [Shamsī] Kasmāʾī Yazdī

Introduction

Shams Kasmāʾī is a prominent figure in contemporary Persian poetry; however, her poetic language and thought have not received considerable attention, for various reasons. Although her ancestry can be traced back to Gilan and the Kasmā region, she was born in Yazd. Due to her husband’s profession, she moved to Eshqabad, and lived for a time in Turkestan under Tsarist Russian rule, where she learned Russian and engaged in cultural and literary activities. The significance of her cultural activities brought her recognition and appreciation from the Iranian government. However, her husband’s financial bankruptcy forced them to relocate to Tabriz, where her literary talent flourished further. She became one of the literary elites of Tabriz, contributing works to the local press and aligning herself with political and intellectual companions, including the famous poet of the Constitutional era, Taqī Rafʿat. Nevertheless, after the assassination of Taqī Rafʿat and the death of her husband, she returned to Yazd and eventually spent the last years of her life in Tehran, continuing her intellectual and literary activities. However, despite her prolific literary career, she left relatively few documents.

Shams Kasmāʾī was influenced by modernity and receptivity to the evolving literature of the contemporary world. Her most important innovation in contemporary Persian poetry was breaking away from the traditional forms of ancient poetry, including rhyme and meter, as did her successor Nīmā Yūshīj. This initiative was a result of the years she spent abroad and her familiarity with literature beyond Iran. The poems she composed during her stay in Tabriz, especially those published in the journal Āzādistān, are among the earliest expressions of modernism in Persian poetry. However, her remaining poems indicate that she was still at the beginning of her artistic journey, and her poetry lacks the technical and prosodic characteristics of Nimaic modern poetry, a style of poetry innovated by the modernist Iranian poet Nimā Yūshīj.

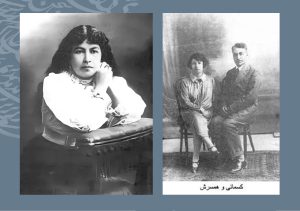

Figure 1- From left: Portrait of Shams Kasmāʾī with her husband.

Research Agenda

Although Shams Kasmāʾī’s life and activities have not yet been the subject of an independent book, several articles have examined her character and her poems. Among those are Muhammad Mahdī Zamānī and Kūrush Safavī’s article “Sabk′shināsī-i intiqādī-i shiʿr-i Shams Kasmāʾī” [Critical stylistics of Shams Kasmāʾī’s poetry],1Muhammad Mahdī Zamānī and Kūrush Safavī, “Sabk′shināsī-i intiqādī-i shiʿr-i Shams Kasmāʾī [Critical stylistics of Shams Kasmāʾī’s poetry], Matn′pazhūhī-i Adabī 22, no. 77 (Fall 1397/2018): 7–31. and Yahyā Āryan′pūr’s book Az Sabā tā Nīmā [From Sabā to Nīmā].2Yahyā Āryan′pūr, Az Sabā tā Nīmā [From Sabā to Nīmā] (Tehran: Zavvār, 1387/2008), 2:456, 2:458. Sīrūs Shukūhī Barādarān’s article “Shams Kasmāʾī: Nahādgār-i khisht-i nakhustīn-i shiʿr-i naw va nidāgar-i andīshah′hā-yi islāhī-i dawrān-i Qajar” [Shams Kasmāʾī: Founder of the first brick of modern poetry and advocate of reformist ideas in the Qajar era], also sheds some light on her work. the works of this Persian poet.3Sīrūs Barādarān Shukūhī, “Shams Kasmāʾī: Nahādgār-i khisht-i nakhustīn-i shiʿr-i naw va nidāgar-i andīshah′hā-yi islāhī-i dawrān-i Qajar” [Shams Kasmāʾī: Founder of the first brick of modern poetry and advocate of reformist ideas in the Qajar era], Rahāvard-i Gīl 6 (Spring and Summer 1385/2006): 75–91.

Nevertheless, due to a lack of access to primary sources about this pioneer of modern Persian poetry, these studies have only examined certain aspects of her personal and intellectual character. One of the major challenges in studying Shams Kasmāʾī is the difficulty of locating her work. Some of her poems can be found in contemporary collections or in journals such as Āzādistān (Khurdād 31/June 21, Murdād 2/July 24, and Tīr 23/July 14, 1299/1920), Jahān-i Zanān, Rūz′nāmah-ʾi Tajaddud, Īrān-i Naw, Shukūfah, and others to which she submitted her work during her lifetime.

Most existing works about Shams Kasmāʾī are extrapolations from the few pages that Yahyā Āryan′pūr wrote in Az Sabā tā Nīmā. Despite numerous efforts, archival documents that reflect Shams Kasmāʾī’s poems have not been found. The few poems that were published in the contemporary press are also difficult to access given the limitations of Iranian media archives.

Shams Kasmāʾī’s Era

During Shams Kasmāʾī’s lifetime, Iran was undergoing significant historical changes. Iranian society was influenced by the political atmosphere of the post-Constitutional Revolution, the occupation of Iran by Russia and England, the failure of Constitutionalism due to foreign intervention, internal tensions, and other events resulting from World War I and its aftermath. This political context had a profound impact on the thoughts and ideas of intellectuals in Iran.

It can be argued that during this era, intellectuals devoted a considerable portion of their works to the political atmosphere, concepts of modernity, and the new ideas shaping Iran after the Constitutional Revolution. In his book Shams Kasmāʾī: Shāʿirah-ʾī bī′daftar va dīvān [Shams Kasmāʾī: A poetess without a collection or divan], Muhammad Rizā Turābi discusses the influence of the literature of the Constitutional period on the political context: “Literature, in general, is primarily a reflection of political revolutions, and literary movements always follow political movements. Secondly, each period has its specific characteristics.”4Muhammad Rizā Turābī, Shams Kasmāʾī: Shāʿirah-ʾī bī′daftar va dīvān [Shams Kasmāʾī: A poetess without a collection or divan] (Tabriz: Qālānbūrd, 1398/2019): 15. Therefore, understanding Shams’s era and the major political events of that period is essential for identifying her poems and analyzing the content and style of her works.

Shams Kasmāʾī (1262/1883 – Mihr 12, 1340/October 4, 1961) witnessed the rule of several Qajar kings and two Pahlavi monarchs. She lived through the final decade of Nāsir al-Dīn Shāh’s reign, the entire reigns of Muzaffar al-Dīn Shāh, Muhammad ʿAlī Shāh, Ahmad Shāh Qajar, and Reza Shah Pahlavi, and nearly two decades of the rule of Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. This 80-year span of contemporary Iranian history encompassed significant and influential events such as the Constitutional Revolution and its aftermath, the coup d’état of Reza Khān in 1299/1921, various uprisings such as the street riots and Āzādistān, Junbish-i Jangal (the Jungle Movement), the fall of the Qajar dynasty, the emergence of the Pahlavi era, and other political and social transformations in Iran, each of which profoundly influenced the thoughts, ideas, and literature of the period.

Iranian literature also witnessed significant changes during this era. Following a decline in Persian poetry during the Safavid period, a fresh spirit emerged in Persian literature during the Qajar era, and narrative literature, poetry, colloquial literature, memoir writing, and other literary genres experienced a resurgence in the Nāsirī period. The trajectory of progress in modern literature and Persian poetry during the Qajar era, especially in its later stages, continued to be influenced by European literature. Each political and social event, especially the Constitutional Revolution, contributed to the creation of new content in the discourse of Iranian writers. The interaction with Europeans in Iran and the infiltration of their ideas into the minds of the intellectual and literary class also played a role. Dialogical expression remained a primary characteristic of Persian poetry and literature of this time, with many Iranian poets expressing their political and social goals in a colloquial tone.

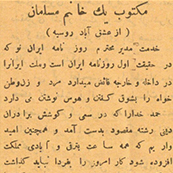

The majority of Shams Kasmāʾī’s activities occurred during the Constitutional era and its aftermath, and the influence of this period can be seen in her poems. Additionally, she lived in Eshqabad, Tabriz, Yazd, and Tehran, and became acquainted with the different cultures and literary schools of these regions. Her innovative deconstruction of the poetry of the Constitutional era resulted from her intellectual interactions with modern European literature, primarily Russian literature. During her time in Eshqabad, she was involved in social activities and consistently focused on her main concern of women’s issues. Her note in the Īrān-i Naw newspaper, titled “Maktūb-i yik khānūm-i musalmān az ʿIshq′ābād-i Rūsīyah” (An epistle from a Muslim woman in Ishqabad) in Russian, is one such instance. Her satisfaction with the opening of girls’ schools and attention to women’s education reflects her commitment to women’s rights.5Shams Kasmāʾī, “Maktūb-i yik khānūm-i musalmān az ʿIshq′ābād-i Rūsīyah” [An epistle from a Muslim woman in Ishqabad in Russian], Īrān-i Naw; as quoted in Rahīm Raʾīs′niyā, “Shams Kasmāʾī”, Chīstā 246 (Isfand–Farvardīn 1386–1387/ March–April 2007–2008): 450–451. One of the most significant events that had a profound impact on Shams’ poems was her presence in Tabriz, which coincided with the final years of Ahmad Shāh Qajar’s reign. The Muhammad Khān Khiyābānī uprising, the political activities of people in Tabriz, the literary works of Taqī Rafʿat, and the literary and scientific gatherings in Tabriz not only influenced the social and political situation of the people in this region but also contributed to the emergence of a new poetic form called Shiʿr-i naw [new poetry].

In addition to addressing the sociopolitical themes and issues of that era, Shams’ poetry also included some of the earliest works in Iranian literature that addressed life and the challenges faced by women.6Shams Kasmāʾī, “Āʾīn-i bartarī” [The doctrine of superiority]; “Jahān-i zanān” [Women’s world]; “ʿĀlam-i nisvān” [The world of women], Āzādīstān (Tabriz), 1299/1920. During a period when Iranian women had minimal rights, Shams openly addressed these challenges in her poems. Although women fought for their basic social rights during the Constitutional Revolution, they were overlooked by society as a whole after the movement succeeded. This reality is well reflected in the legislation passed by the Constitutional Parliament of Iran.7Sumayyah Balbāsī and ʿAlī Rizā Khazāʾilī, “Nīmah-ʾi duvvum: Haqq-i raʾy va namāyandigī” [The second half: Suffrage and representation], Zamānah 5, no. 48 (1385/2006): 42–45.

The Life of Shams Kasmāʾī

Shams Kasmāʾī, also known as Shamsī, was a contemporary Iranian poet born in 1262/1883. According to Āryan′pūr in Az Sabā tā Nīmā, Kasmāʾī’s family migrated from Georgia to Iran during the rule of Āqā Muhammad Khān Qajar and dispersed across various parts of Iran, settling in cities such as Qazvin, Yazd, and Tabriz.8Āryan′pūr, Az Sabā tā Nīmā, 2:457; Muhammad Rizā Turābī (Rizā Hamrāz), Sayrī dar tārīkh-i inqilāb-i mashrūtah: Taʾsīr-i qiyām-i mardum-i Tabrīz va Āzarbāyjān dar pīrūzī′hā-yi inqilāb-i mashrūtiyat [A survey of the history of the Constitutional Revolution: The impact of the uprising of the people of Tabriz and Azerbaijan on the victories of the Constitutional Revolution] (Tabriz: Yārān, 1389/2010), 77. Sardārī′niyā notes that the roots of Shams’ family can be traced back to the village of Kasmā in Gilan, and her father Khalīl, the son of Hāj Muhammad Sādiq Kasmāʾī, moved from this village to Yazd.9Samad Sardārī′niyā, Tabrīz: Shahr-i avvalīn′hā [Tabriz: The city of the firsts] (Tabriz: Kānūn-i Farhang va Hunar-i Āzarbāyjān, 1381/2002), 243. Sardārī′niyā sees no connection between the migration of the Kasmāʾī family from Georgia to Iran and other regions. See Barādarān Shukūhī, Shams Kasmāʾī, 75–77. Khalīl and Humāyūn, Shams’ mother,10Turābī, Shams Kasmāʾī, 10. were married in Yazd, and Shams was born in 1262/1883. Shams lived in several cities and acquainted herself with different cultures and languages, such as Russian and Turkish. This exposure influenced her poetry and intellectual thoughts significantly. She had two children from her marriage to Husayn Arbāb′zādah: a daughter named Safā and a son named Akbar. After several years, the family migrated from Yazd to Eshqabad, in Russian territory. During this time, Shams developed a deep understanding of Russian culture, literature, and language. However, Arbāb′zādah, who was engaged in trade, went bankrupt after the 1269/1917 Revolution in Russia,11Raʾīs′niyā, “Shams Kasmāʾī,” 454. and after ten years in Eshqabad, the family moved to Azerbaijan.12Āryan′pūr, Az Sabā tā Nīmā, 457; Barādarān Shukūhī, “Shams Kasmāʾī,” 77; Turābī, Shams Kasmāʾī, 10. In Tabriz, Shams composed and published some of her poems and also participated in various activities. Her acquaintance with Taqī Rafʿat and the activists of the Street Movement and Āzādīstān took place during this time. Shams experienced many bitter events in her life, including the loss of her husband and their young son, Akbar, during their years in Tabriz. In 1299/1920, Husayn Arbāb′zādah assumed an honorary representation role in Maʿārif-i Shabistar, serving until the end of 1305/1926 and resigning from his position in 1306/1927. Shukūhī Barādarān considers this year to be the probable date of his death.13Shukūhī Barādarān, “Shams Kasmāʾī,” 77; quoted in Tārīkh-i farhang-i Arūnaq va Anzāb, sharh-i muʾassisāt-i farhangī-i ān [History of the culture of Arūnaq and Anzāb, description of its cultural institutions] (Tabriz: Shafaq, 1338/1960). In his book, Turābī records the death of Husayn Arbāb′zādah as occurring in 1307/1928. See Turābī, Shams Kasmāʾī, 10. Shams’ son Akbar, a painter and poet who was fluent in French, also lost his life due to his political activities. After the onset of the Jungle Movement (Junbish-i Jangal) in Iran (1300/1921), Haydar Khān, an important figure in the Constitutional Movement, entered into negotiations with Mīrzā Kūchak Khān. Their meetings took place at the residence of Muhammad Reza Khān Rafīʿī, the master of Mullāsarā village. However, their collaboration turned into conflict, leading to challenges for both groups, and the residence was attacked.14Bashīr Sirājī and ʿAbd al-Rahīm Qanawāt, “Vākāvī-yi guzārish′hā-yi vāqiʿah-ʾi Mullāsarā va qatl-i Haydar ʿAmū′ughlī dar nihzat-i jangal bā tikyah bar ravish-i mihvar′hā-yi maʿnā′dihī-i Stānfurd [Analysis of reports on the Mullāsarā incident and the murder of Haydar ʿAmū′ughlī in the Jungle movement with an emphasis on Stanford meaning-making methods], Fasl′nāmah-ʾi ʿIlmī-i Mutāliʿāt-i Tārīkhī-i Jang [Scientific journal of studying the history of war] 3, no. 3 (Ābān 1398/November 2019): 42–43. Haydar Khān was believed to have been killed on the Ābān 5, 1300/October 27, 1921, and Akbar also became a victim of internal conflicts among the members of Jungle Movement. Unfortunately, historical records and documents regarding military participation, political activities, and even the death of Akbar Arbāb′zādah are not available.

Abū al-Qāsim Lāhūtī, one of the revolutionaries and prominent poets of that era and a companion of Shams, composed the poem ʿUmr-i gul (The life of a flower) in Tabriz in Ābān 1300/November 1921, mourning the loss of Akbar:15Jalīl Amjadī, “Shams Kasmāʾī: Zan-i pīshgām-i shiʿr-i naw” [Shams Kasmāʾī: The pioneer woman of modern poetry], Gīlah′vā 6, no. 45 (Ābān–Āzar 1376/November–December 1997): 7–8; Abū al-Qāsim Lāhūtī, Dīvān (Moscow: Foreign Language Publications Directorate, 1946), 451.

Oh, nightingale, in parting from your rose,

Do not raise a cry nor mourn

Exercise patience and remain steadfast,

Do not let your hair become tangled like hyacinths

You, who with the light of celestial knowledge,

Are the highest form of humanity,

The pride of the Iranian people,

You know better than anyone else,

For two days has lived the flower.

There are two narratives about the activities and death of Akbar. Shukūhī Barādarān believes he was a member of the Committee of Haydar ʿAmū′ughlī, while Turābī refers to Akbar as a young comrade of Mīrzā Kūchak Khān Jangalī.16Turābī, Shams Kasmāʾī, 12. The impact of her son’s death was profound on Shamsī, leading her to become reclusive. Along with her daughter Safā Khānūm, she relocated to Yazd; after five years, she migrated to Tehran, where she passed away in 1338/1959.17Barādarān Shukūhī, “Shams Kasmāʾī,” 77. There are different accounts regarding the time of Shams Jahān Kasmāʾī’s death. As Barādarān Shukūhī has noted, Pūrān Farrukh′zād gave her age at the time of death as 87, while Samad Sardārī′niyā marked her age as 78 in 1341/1962 when she died in 1962,18Sardārī′niyā obtained his information from Shams Kasmāʾī’s daughter Safā Khānūm. See Barādarān Shukūhī, Shams Kasmāʾī, 76; Sardārī′niyā, Tabrīz, 253., a date Āryan′pūr also confirms. On her tombstone, the date of her demise is engraved as the year 1341/1962.

Figure 2- Shams Kasmāʾī ’s letter to Īrān-i Naw, 1327 AH (1909 CE) from Ashgabat, Russia, discussing girls’ schools and women’s employment.

Works of Kasmāʾī

Shams composed a significant portion of her works in the turbulent and revolutionary era of Qajar. She was inspired by and learned much from Taqī Rafʿat, and one of the strongest features of her poetry is its vibrant spirit. In contrast to their contemporaries, Shams’ and Rafʿat’s poetry concentrated on their current sociopolitical situation and introduced innovations in the poetic form. This is why many scholars of Persian literature trace the origin of modern poetry not to Nīmā’s poems, but to those of Shams Kasmāʾī and Taqī Rafʿat.

In Persian literature, women were traditionally and historically defined and described based on men’s perspectives, and the literary activities of women, though more extensive than other subjects, were shaped by such viewpoints. During the Constitutional Revolution, changes in political thinking and relative modernization in society led to an increase in women’s activities,.19Rūh′angīz Karāchī, “Mashrūtah va zanān-i shāʿir” [The Constitutional Revolution and women poets], Rūdakī 9 (Day 1386/January 2007), 46–52. which, in turn, caused a transformation in literary content. Shams’ literature is a product of this period and follows the same literary system. By this time, the existing social and political situations had a significant impact on literary works. Shams’ verses reflect the chaotic conditions before the Constitutional Revolution, foreign interventions, the interference and plundering of foreigners, the relative backwardness of Iranian women compared to women in the West, the neglect of women’s status, and the inequality of women’s rights compared to men in society.

The influence of the Tabriz intellectuals is also clearly visible in Shams’ poetry. Taqī Rafʿat, one of the most important social and political figures of the Constitutional Revolution, engaged in extensive cultural, political, and social activities during the Constitutional Movement in Iran, which inspired the publication of the journals Tajaddud and Āzādīstān. In addition, he pioneered modern Persian poetry and composed verses with different content and forms than predecessors had left behind. Shams Kasmāʾī was a companion and disciple of the same school.

The most important feature of this period was modernism. During this time, Persian poetry was divided into two categories: new and old.20Barādarān Shukūhī, “Shams Kasmāʾī,” 80. Shams and Rafʿat were pioneers of modern poetry, and their works show significant differences from traditional poetry. Although there is no complete collection of poems, many of her verses have been collected from various historical/literary texts. Some of her poems were published in issues of Āzādīstān and other newspapers of that period, which are accessible today; for example, “Falsafah-ʾi umīd” (Philosophy of hope), “Madār-i iftikhār” (Orbit of honour), and “Parvarish-i tabīʿat” (Cultivating the nature) were published in Āzādīstān in 1299/1920. These poems demonstrate her ground-breaking role in the field of modern poetry, both in terms of content and poetic style. A significant portion of these were composed in the post-Constitutional revolution era and during the uprising in Tabriz. Shams’ poetry reflects the vibrancy and energy of her youth, at the height of her social and political activities. However, personal life challenges, hardships, and the grief of losing her husband and young son deeply affected Shams’ spirit and led to her period of seclusion during the Pahlavi era. Her son Karīm Arbāb′zādah joined the guerrilla struggles towards the end of the Jungle Movement and was killed in one of the battles in 1299/1920. As a sign of his admiration and affection for Shams, composed a poem mourning her son.21Abū al-Qāsim Lāhūtī, Dīvān (Moscow: Foreign Language Publications Directorate, 1946), 451.

Kasmāʾī’s Status in Contemporary Persian Poetry

The poems of Shams and her contemporaries brought about a transformation in the theme of Persian poetry. Although the subjects of Persian literary works can be examined as a unified category that has changed little over time, the themes of these works have changed in different periods. In explaining the difference between the theme and the subject, Māshā Allāh Ājūdānī notes:

In terminology, theme differs fundamentally from the concept of topic or subject. This is because the themes of various artistic works may involve different thoughts or perspectives on a single topic… In other words, we use the term “theme” in a developmental sense that encompasses both the conceptual sense and the subject.22Māshā Allāh Ājūdānī, “Darūnmāyah′hā-yi shiʿr-i mashrūtah” [Themes in the poetry of the Constitutional Revolution], Īrān′nāmah 11, no. 4 (Fall 1993): 621–46.

Ājūdānī suggests that although the themes of Persian literary works have changed, the subject matter has not changed significantly and has mostly been structured around elements such as homeland, love, mysticism, and similar concepts. The themes of Constitutional Revolution poetry can be divided into several categories: homeland and national identity, political and cultural freedom, Western modernity, and social and political criticism.23Ājūdānī, “Darūnmāyah′hā-yi shiʿr-i mashrūtah,” 622. Social and political conditions have been influential factors in contemporary Iranian literature, including Kasmāʾī’s poetry, setting these works apart from earlier and classical Persian poetry and literature.

Persian poetry encompasses various styles that can be analyzed according to geographical regions, human characteristics, and the cultural nuances of each area. One of these is the Āzarbāyjānī style, whose distinctive features Muzaffariyān identifies as complex discourse and rational, philosophical, and social themes, in contrast to the Iraqi style, which is characterized by emotional expression and a softer, more refined discourse.24ʿAlī Rizā Muzaffariyān, “Vīzhigī′hā-yi bunyādīn-i sabk′hā-yi shiʿr-i Fārsī [Fundamental features of Persian poetry styles],” Tārīkh-i Adabiyāt (Pazhūhish′nāmah-ʾi ʿulūm-i insānī) [The history of literature (A journal of humanities)] 4, no. 3/71 (Fall and Winter 1391/2012): 270–73. Despite its significant developments in the field of Persian literature, Shams’ poetry is mainly in the Āzarbāyjānī style. Her poetic style, compared to the modern poetry of Nīmā, exhibits a certain complexity in its discourse. Structurally and thematically, Shams’ poetry differs significantly from past works, but does not share the same stylistic fluidity as Nīmā’s poetry. One reason for the limited attention to Shams’ works, despite her formative role in modern Persian poetry, stems from the challenging tone and rational-philosophical content of her poetry. These aspects place her work at what may seem like a lower level in the eyes of the general audience, especially when contrasted with Nīmā’s emotionally driven and rational verses. Nevertheless, Kasmāʾī holds a prominent position among contemporary Iranian female poets, and her poetry demonstrates a strong dedication to the spirit of her time.

Shams Kasmāʾī’s Iconoclastic Role in Social Norms and New Persian Poems

With the change in the Iranian government and the establishment of the Constitutional Revolution came similar changes in the demands and needs of society. Similarly, the intellectuals and writers in Iran who were responsible for articulating these demands recognized the need for change and evolution. Following the Constitutional Revolution, new themes were introduced into Persian poetry. The previously dominant themes of love and mysticism were no longer as prevalent; instead, freedom, prosperity, social and political rights, and, most importantly, critiques of existing political, economic, and social conditions became the central themes in Persian poems and other literary works. During the Constitutional era, poets were divided into two main categories. The first consisted of followers of traditional and old Persian poetry, characterized by its complex structure, with their main audience being the educated class, the king, and government officials. The second group, on the other hand, consisted of poets advocating for a departure from the old style, aiming to write poetry for the general public.25Amjadī, “Shams Kasmāʾī,” 6.

The creation of a style that could convey more effectively the new themes of the Constitutional era required a transformation in the cumbersome poetic forms of the past. The second aforementioned group of poets, known as the modernist and revolutionary literati, also sought to establish such a style. During this time, a confrontation emerged between the two styles of old and new poetry. Representatives of the old style published their works in the journal Dānish′kadah (Literally: faculty), managed by Malik al-Shuʿarā Bahār, while Tajaddud and Āzādistān, under the management of Taqī Rafʿat, represented the new style.26Amjadī, “Shams Kasmāʾī,” 6.

Shams Kasmāʾī was one of the pioneering poets and progressive thinkers who was associated with Taqī Rafʿat. She, in introducing new content to Persian poetry, saw the solution in changing the structure and adopting the format of Taqī Rafʿat’s poems. Rafʿat, Jaʿfar Khāminahʾī, and Shams Kasmāʾī were three leading figures in the formation of modern poetry,27Amjadī, “Shams Kasmāʾī,” 7. who believed that the needs of contemporary society could not be expressed adequately through the poetic style of Saʿdī and Hāfiz. Additionally, they believed that with the introduction of new and relevant subjects into Persian literature came a need for a revolution in the poetic style and structure.28Amjadī, “Shams Kasmāʾī,” 7.

These three poets were the founders of the structural transformation in modern Iranian poetry and literature and laid the groundwork for change in traditional literature with their works. Seventeen years before Nīmā Yūshīj’s revolutionary poem Quqnūs (The Phoenix),29Muhammad Rizā Shafīʿī Kadkanī, Advār-i shiʿr-i Fārsī az mashrūtīyat tā suqūt-i saltanat [The eras of Persian poetry from the Constitutional Revolution to the fall of the monarchy] (Tehran: Tūs, 1359/1980), 145. Shams Kasmāʾī wrote “Parvarish-i tabīʿat,” published in the fourth issue of the Āzādīstān journal in 1299/1920.30Firishtah Pīsh′qadam, “Barrisī-i furmālīsm dar ashʿār-i Shams Kasmāʾī: Mādar-i shiʿr-i naw” [A formalist study of Shams Kasmāʾī’s poems: The mother of modern poetry], Rahāvard-i Gīl 15, no. 111 (Khurdād–Tīr 1399/June–July 2020): 50. The style of this poem was influenced by the European modernist poems that she read while living in Eshqabad. Kasmāʾī introduced new concepts, such as women’s rights and gender equality, into Persian poetry, and used asymmetric and unequal verses in her works to convey these themes. Given the novelty of this style in Persian poetry and the conflict between advocates of traditional and modern poetry, Shams’ poetry struggled to reach its full potential in terms of tone; therefore, her poetry received less attention from audiences and critics of modern poetry than Nīmā’s, which was seen as more effectively expressing depth and emotion.

Concepts and Themes in Shams Kasmāʾī’s Poetry

In addition to addressing contemporary issues and the sociopolitical conditions of Iran, the central themes in Shams Kasmāʾī’s poetry include independence and freedom for women, gender equality, nationalism and national identity, anti-alienation, and hopes for a better future. Her works draw inspiration from ancient times to highlight women’s essential roles and ideals in society and address the social regression of Iran. In terms of thematic classification, her works can be categorized into four different subjects:

- Women’s Rights: “ʿĀlam-i nisvān” (World of women), “Āyīn-i bartarī” (The doctrine of superiority), “Jahān-i zanān” (Women’s world)

- National Identity: “Ashraf-i makhlūqāt”(The noblest of creatures), “Madār-i iftikhār” (Orbit of honour), “Falsafah-ʾi umīd” (Philosophy of hope)

- Political and Social Conditions: “Falsafah-ʾi umīd” (Philosophy of hope), “Parvarish-i tabīʿat” (Cultivating nature) “Iqtizā-yi zamān” (The demands of the times)

- Critical Poetry: “Ashraf-i makhlūqāt”(The nobles of creatures), “Madār-i iftikhār” (Orbit of honour), “ʿAmal” (Action) “Jahān-i zanān” (Women’s world)

In “Ashraf-i makhlūqāt,” Shams upholds patriotism and criticizes foreign influence. She praises her homeland and its resources, and condemns the plundering of those resources by and for foreign interests:

My homeland is on the Earth, not within the moon’s cavity.

Beneath my feet, all is gold; I won’t go begging from my neighbours.

In the world, the Iranian nation is known for its authenticity.

My thoughts, hopes, and perspectives revolve around this point.

In another section of this poem, Kasmāʾī also highlights Iranians’ indifference towards foreign occupation of the country:

The difference between me and His Excellency, the Human, is this:

He is perceptive and attentive, while I am mere dust and dirt.

“Falsafah-ʾi umīd” is a praise of Shams’ predecessors and their work for the liberation and freedom of the Iranian people. In this poem, Shams metaphorically refers to a past that brought tranquillity and prosperity to the Iranian nation, using the Constitutional Revolution as a symbol and depicting the subsequent ruin during the rule of Muhammad ʿAlī Shāh Qajar, as well as the corruption that intruded the Constitutional Movement. She explicitly states that reconstructing this ruin is her duty and that of her contemporaries. In the following passage, she alludes to street protests and the movement of freedom-seekers:

Fortunately, we gathered clusters

That people seeded with their souls before us

We were the farmers of the past

Now it’s our turn to cultivate the future

Another important concept highlighted in “Falsafah-ʾi umīd” is the companionship and solidarity of the Iranian people in times of crisis, even alongside various critiques of the contemporary situation in Iran and of various problems in the nation and the government:

If we are together or scattered,

In nature, we are steadfast.

If for a moment we fade, we are still present!

“Madār-i iftikhār” similarly revolves around the theme of national identity and pride for Iranianness while criticizing the decisions of kings and authorities. In this poem, as in “Ashraf-i makhlūqāt,” she declares her pride in, and defends, her Iranian identity:

Far be it for our voice to be at the mercy of supplication,

Our dignity shall always be our reliance.

An Iranian is proud of their own race!

In another section, she alludes to the danger posed by the Shah and the authorities’ desires for wealth, riches, and positions, which threaten the Iranians. With these references, she aims to raise awareness among the Iranian nation, especially the people of Azerbaijan:

Until humanity’s support was silver and gold,

Never expect the brotherhood to rely on pledges!

As long as justice lacks power, equality is in vain!

Negligence is a danger for the nation in the East!

Another important theme in “Madār-i iftikhār” is a warning against the real intentions of foreigners towards the Iranian nation. The actions of foreign powers, although seemingly benevolent and in favour of the Iranian people, are inherently detrimental to the nation and the country. They act as obstacles to the Iranian people achieving their inherent rights:

Those who have cast an eye beneath our feet,

Hidden the blade of greed beneath our cloak,

They intend to seize the sun and moon.

In addition, “Madār-i iftikhār” can also be read as a defence of the Āzādīstān journal, which was accused of separatism during that time, and its intellectual atmosphere. However, the publication of this poem, and other instances of emphasis on the homeland, was seen as a sign of support from intellectuals in that region, particularly the Āzādīstān journal, for nationalism.

In “ʿAmal,” Shams compares Asia and Eastern countries to Europe and developed countries, calling the former negligent and backward when set beside the latter. She attributes this to the indifference of the people in these regions, despite their long history and high capabilities, who, instead of taking positive steps towards independence and prosperity, remain stagnant, while Europe continues to progress every day. Shams’ statements in this poem are influenced by her life in the Russian domain and his encounter with European thought:

The West excels in effort and the invention of airplanes,

While we [= Eastern countries] are cornered or neglected due to a lack of action.

Asians, satisfied with humility, are anonymous and belittled,

Unaware that Europe has triumphed in competition.

The majority of Shams’ attention was devoted to women’s rights, freedom, and liberation from outdated thoughts. Three of her poems, “ʿĀlam-i nisvān” (World of women), “Āyīn-i bartarī” (The doctrine of superiority), and “Jahān-i zanān” (Women’s world), address these concerns amidst the revolutionary atmosphere in the contemporary poems of Iranian women. All three poems focus on awareness of women’s rights, criticism of traditional ideas and thoughts within families, comparison of the social status of Iranian women with that of women in the Western world, and concerns about childhood, education, and the spirituality of women.

“ʿĀlam-i nisvān” marked a significant transformation in the content of Shams’ poetry. She drew inspiration from ancient times and attempted to reconstruct the position of women in contemporary society by connecting it with that era. She also expresses concern that men have defined the identity of women according to their own desires. This work reflects Shams’ efforts toward the recognition and promotion of women’s rights and their liberation from cultural and traditional constraints.

In “ʿĀlam-i nisvān”, Shams calls upon women to strive to obtain their freedom and rights, as well as engage in any activity solely based on their desires:

Until when is this solicitation for love?

Under command and obedience, until when?

Subject to reproach and blame, until when?

The imposition of obligations, until when?

“Āyīn-i bartarī” similarly denounces the lack of gender equality in Iran, a groundbreaking subject area in the period following the Constitutional Revolution. In a critical tone, Kasmāʾī addresses this theme:

Hundreds of thousands of men, soldiers of an army,

Where have the women of the country gone?

Perhaps in the sophisticated world,

The grand tradition and the superior ritual are being woven.

“Jahān-i zanān” supports and raises awareness of women’s rights by criticizing traditional views, promoting the liberation of young girls, and creating a new definition of success for women. At that time, the success of a girl was limited to marriage in early adolescence and competing to secure a better husband. Shams criticizes this mindset and condemns Iranian families’ insistence on marrying off their teenage girls and preventing them from achieving scientific and professional successes:

How long the desire for adornment and being occupied with makeup

How long the pursuit of customers and the thought of buyers

This dress is worn out, be proud of your dignity

The poem also compares Iranian women unfavourably to those in more developed countries:

The Iranian maiden lags behind the caravan of knowledge,

In front of you, a desert without water and full of thorns.

In the new century, your same-sex counterpart soars like a bird,

While you, like a beast, have given your head to the snare.

Equality of rights between women and men is a common theme among “ʿĀlam-i nisvān,” “Āyīn-i bartarī,” and “Jahān-i zanān.” “Jahān-i zanān” reminds readers that the world is moving towards establishing political, social, cultural, and economic equality for all humans. The poem emphasizes the significance of collaboration and companionship between women and men to advance national goals. However, it questions why, in Iran, instead of uniting and cooperating, individuals often confront one another and engage in internal conflicts, in a misguided tendency to prioritize infighting over collectively opposing a common adversary:

It is the era of freedom and the day of liberation,

Why are we, women and men, at odds with each other?

What benefit does tearing the garment of negligence bring?

It is time for this turmoil and tumult to come to an end.

Shams Kasmāʾī always had concern for the people of Iran, particularly girls, revolution, freedom, and escaping the snares of foreigners and tyrannical rule. The poem “Parvarish-i tabīʿat,” one of her best-known works, reflects her inner sentiments and the unfavourable state of her times, marked by war, internal conflicts, the trampling of women’s social rights, despair, and disillusionment during the turbulent era after the Constitutional Revolution, and numerous other social ills:

From the intense fire of love, coquetry, and caresses,

From this intensity of warmth, brightness, and radiance,

The garden of my thoughts

Became ruined and distraught, alas!

No ally of goodness,

No power of shame,

Neither arrow nor sword was mine, nor a sharp tooth,

No power to escape,

Pressed by the pressure of my kind.

I am beside myself from the world and the path of world-worshippers.

Shams Kasmāʾī composed numerous poems throughout her life, and it is reported that she had a notebook containing more than 500 couplets. However, only a limited number of her poems are accessible. The novel themes and transformations present in the works that are available to us eloquently express the importance of Shams’ poetry and her innovative perspective. After mourning the loss of her husband and child, Shams became reclusive and limited her presence in literary circles; after a brief return to Yazd, none of her works were published in journals.

Literary Analysis of Shams Kasmāʾī’s Poetry

Use of New Vocabulary and Concepts

Shams Kasmāʾī was a progressive poet who incorporated the vocabulary of her era into her work. Her focus on modern themes and innovations made her a poet of her era. Words such as Europe, airplane, civilization, freedom, and fashion reflect her attention to contemporary issues. In her writing she focused on both East and West, the contrast and equality of women’s and men’s rights, the concept of honour, the wellbeing of the oppressed, the ignorance and negligence of Iranians, and the importance of education.

Use of Archaic Vocabulary

In some of her poems, Shams Kasmāʾī, influenced by the dīvāns (collection of poetry) and the works of classical Persian poets, used classical literary forms derived from poems that frequently appeared in traditional collections. Some of the words she uses are Arabic, such as muttahid al-hal (unified state), sīm-u zarr (silver and gold), shams-u qamar (sun and moon), bahāʾim (livestock), and sometimes Persian, like az chih rūy (why), bar ānam (I intend), bādīyah (desert), ahl-i yaqīn (people of certainty), tīgh (sword), and so on. She particularly emphasized concepts related to Iranian heritage, such as mul-i jam (King Jamshid’s territory), tāj-i kiyānī (Royal crown) and dukht-i Parsī (Persian girl), and these references reflect her admiration for past glories and her patriotism.

Breaking the Chain of Language in Couplet Structure

The rhyme, rhythm, and structure of couplets are key elements in constructing a poem. Shams Kasmāʾī was not an exception to this rule; however, at times, these interventions resulted in syntactic errors for her. For instance, one couplet appearing in “Āyīn bartarī” is “Where did the country’s women have gone?” The use of two interrogative markers together is grammatically incorrect in Persian. Another poem, “Madār-i iftikhār,” includes the line “Īrānī az nizhād-i khvudash muftakhar būd” (Iranians were proud from their race), using the word az (from) rather than the more grammatically correct bih (with).

Use of Simile

The most effective literary device in Shams’ poetry is metaphor, especially the balīgh (explicit). Her metaphors often present entirely new and constructed images, such as dūshīzah-ʾi Īrānī (Iranian maiden), qāfilah-ʾi ʿilm (caravan of knowledge), jāddah-ʾi ghiflat (the path of ignorance), gulistān-i fikr (the garden of thought), ātash-i mihr va nāz va navāzish (fire of affection and charming coquetry), tīgh-i tamaʿ (the sword of greed). One particularly striking example appears in “Parvarish-i tabīʿat”:

Like withered flowers,

My fresh thoughts

Have become hopeless, spilled from my palm.

Use of Irony

Shams Kasmāʾī’s poetry often features literary irony, enhancing the appeal of its language. Some examples include the phrases pāy dar dāman-u sar dar zānū nishīnam (I sit with my feet tucked in my skirt and my head on my knees), mā zan-u mard az chih rūy sar dar garībān (why do we, men and women, surrender our heads in despair?), and jāmah-ʾi ghiflat chih sūd chāk nimūdan (what is the use of tearing apart the garment of negligence?).

Use of Contrast

Contrast is also featured in Shams’ poems, such as that between Asia and Europe in “ʿAmal”. The interplay of opposing elements enriches the layers of meaning in her poetry:

An Asian being content with humility and anonymity,

Unaware that Europe is defeated in competition.

Other examples of contrasts include the following passages:

I am neither a helper of goodness,

Nor a cause of badness.

…

Sometimes a receiver, sometimes a giver,

At times oppressive, at times shining bright.

Though we are united, or scattered.

Use of Repetition

One particular example of Shams’ use of repetition in her poetry is the repetition of the verb shud (became) in the poem “Jashn-i Īrān” (Iran’s celebration):

The Iranian’s zeal at the cost of life became,

Whatever became, became according to the need of the time.

Breaking the Traditional Poetic Forms

Shams Kasmāʾī’s remaining poems include three ghazals, a poetic form that originated in Arabic literature and was later popularized in Persian, Turkish, and Urdu traditions, that adhere to all the principles governing the construction of a ghazal, such as rhyme, attention to the vertical axis of the poem, and the number of verses. These ghazals demonstrate her study and understanding of this form. However, many of her other poems do not conform to the conventional frameworks of Persian poetry. Shams, indifferent to the rigid traditional rules of rhyme, seeks to bring about a transformation in Persian poetry by introducing changes in the use of rhymes. Her innovation and attention to the needs of her time in shaping this thinking have not been without influence.

For example, in “Falsafah-ʾi umīd,” verses 1 and 4 rhyme with each other, and 2 and 3 rhyme, violating the rules of any traditional poetic form. Additionally, verses 6, 7, 8, and 9 also rhyme with each other, as do verses 5 and 11, which is an unusual use of rhyme in Persian poetry. In “Mud va muhabbat” (Fashion and affection), verses 1 and 2, 3 and 4, and 5 and 6 rhyme, a scheme that also appears in “Madār-i iftikhār” and “Parvarish-i tabīʿat”.

Shams’ use of rhymes in each verse of her poems was a technical skill that Nīmā Yūshīj later employed in his works, marking a new path for Persian poetry. Examining Shams Kasmāʾī’s poetry suggests that she felt the need to change the basic structure of Persian poetry, an endeavour to which she devoted much attention; in so doing, she laid the groundwork for Nimaic poetry and modern Persian poetry.

Breaking the Rule of Prosodic Elements

Shams uses various forms and meters typically associated with classical Persian poetry, such as such as ramal musammin makbūn muzmar in poems like “Ashraf-i makhlūqāt” and “ʿAmal”; munsarah musamin mujawwad manhūr in “Jahān-i zanān” and “Jashn-i Īrān”; ikhrib mukhaffaf muhazzaf muzmar in “Mud va muhabbat” and “Madār-i iftikhār”; and mujannūn muhazzaf muzmar in “Falsafah-yi umīd” and “Parvarish-i tabīʿat.”

This poem, written in the meter mutighārib musmin sahīh, consists of four metrical feet, and according to the rules of classical poetry, these four feet should be repeated in each hemistich. However, Shams instead uses four feet in some hemistichs and two feet in others, which was unprecedented in Persian poetry:

Neither arrows nor my sword, no sharp teeth,

Nor do I have fleeing legs.

This practice was also considered a fundamental rule in Nimaic poetry after Shams, and poets were free to adjust metrical feet based on the content of the poem. Shams Kasmāʾī should be regarded as an innovator or a source of inspiration for Persian modernist poets in this regard.

A Selection of Shams’ Poems

Falsafah-ʾi umīd (Philosophy of hope)

In these five-day cycles of our destiny,

How many cultivated fields have we witnessed?

Fortunately, we’ve harvested clusters

Sown by people with life’s aspirations.

We were the farmers of the past,

Now, we’re cultivating the future.

At times a receiver, at times a giver,

Sometimes oppressed, occasionally shining.

Though we are scattered or gathered,

In nature’s course, we endure.

If for a moment we fade away, we reappear. 31Shams Kasmāʾī, “Falsafah-ʾi umīd” [Philosophy of hope], Āzādīstān (Tabriz), no. 2 (Tīr 15, 1299/July 6, 1920).

Madār-i iftikhār (Orbit of honour)

Until the foundation of human nature was gold and silver,

Never expect a pact of brotherhood!

Until the right is powerless against equality!

Negligence was a danger for the Eastern nation!

They, who had woven their eyes under our feet,

Concealed the dagger of greed in our sleeves.

Their purpose was to dominate the sun and moon.

May our voice never come to a plea,

The Iranian was proud from his own race! 32Shams Kasmāʾī, “Madār-i iftikhār” [Orbit of honour], Āzādīstān (Tabriz) 3 (Isfand 20, 1299/March 11, 1920).

Ashraf-i makhlūqāt (The noblest of creatures)

If I am the noblest of creatures, of the human race,

Then why, like a beast, am I burdened with oppression?

If I am truly Adam, created by fate,

In front of strangers, I am ashamed and without skill.

The difference between me and the Lord of mankind is this:

He is all-seeing and all-hearing, while I am mere dust.

My homeland is on the Earth, not within the moon,

Beneath my feet, all is gold; I bear no weakness to my neighbour.

In the world, the Iranian nation is known for its authenticity,

At this very point, my thoughts, hopes, and views reside.

Mud va muhabbat (Fashion and affection)

A woman needs less to attract love,

Forced into fashion and occupied with make-up.

How long will this pursuit of love continue?

Under command and obedience, how long?

Subjected to reproach and blame, how long?

When will these imposed obligations last?

Oh, daughter of Persia, remember the past times.

Shameful is captivity, break free from the chain of disgrace,

Soar to the heights of bliss, like an angel!

Tabriz, Tīr 2 1299 (23 June 1920)

ʿAmal (Action)

We, born in the East, from the fountainhead of light,

Why are we distant from civilization, lost in ignorance’s night?

The West, with effort and inventive action, took to the skies,

While we, lacking action, remain neglected, idle, and shy.

Oh, radiant light, why have you made me so

Silent, veiled, and hidden, why this status quo?

Having been enriched by nature’s bounty, I stand free,

No need for possessions, no lack of wealth do I see.

A mill, hidden in humility and disdain,

Unaware that Europe is defeated in the competition, in pain.

Āyīn-i bartarī (The doctrine of superiority)

In the ancient realm of Jam, a pleasant sight is seen,

Hundreds of thousands of men, men of the army keen.

Where have the women of this land gone?

Those who, for centuries, were the leaders and the dawn.

Perhaps they are hidden in the world,

The grand tradition and the ceremony of superiority.

For without wisdom, we are unaware,

Of the kindness of a sister, the grace of a brother.

Jahān-i zanān (Women’s world)

In the presence of the wise and conscientious,

The discourse becomes delightful, an epic of women.

An era of freedom, a day of liberation,

Why are we, men and women, at odds and in confrontation?

What use is the garment of ignorance torn open?

The time has come to end the tumult and commotion.

Muslim women, like a mural on the wall,

Unaware, indifferent, and idle due to the time’s call.

The Iranian maiden lags behind in the caravan of knowledge,

In front of you, a wilderness without water, full of thorns.

In the modern century, like a bird in flight,

You, like animals, have given yourself to the snare.

When our mother is not proud and biased,

It is not a disgrace to sell one’s child.

How long is the desire for adornment and preoccupation with vanity?

How long is the pursuit of buyers and the thought of the buyer?

Discard this sleeping garment, express your pride,

The Kianian crown is what you truly deserve.

Beware, if a particular nation adheres to the truth,

Islamophobia is not the lowliness of thoughts.

Parvarish-i tabīʿat (Cultivating nature)

From the intensity of love, coquetry, and caress,

My thoughts, like withered flowers, became a mess.

The garden of my mind has become ruined and distressed,

Like withered flowers, thoughts become wild.

Freshness and purity have become hopeless,

Indeed, foot on the hem, and head bowed low,

Like a half-savage trapped in a land,

No good fortune for me, no power of shame.

No arrow, no sword, no sharp teeth,

No legs for escape.

Thus, I am under the pressure of my like-minded,

I have turned away from the world and those who worship it.

From the world, away from worldliness, I am indifferent,

A mill, hidden in humility and disdain.

Unaware that Europe is defeated in the competition.

Jashn-i Īrān (Iran’s celebration)

In the young days of May,

A time of joy and revelry, the world on display.

The night’s darkness disappeared, the sun revealed,

Unified, the East and the West, the world was healed.

The time of comfort for the suffering arrived,

The pride of Iranians, for the price of life, survived.

All that happened, happened as per the time’s need.