Polyphony in the Poetry of Rawyā Taftī

Introduction

Rawyā Taftī [Roya Tafti] is one of the most distinctive voices in contemporary Iranian poetry, emerging from the postmodern literary scene of the 1370s/1990s alongside poets influenced by Rizā Barāhanī and the “Language Poetry Movement.” Her poetry stands out for its resistance to singular narrative, its embrace of fragmented expression, and above all, its commitment to polyphony or the coexistence of multiple, independent voices within a single poetic structure. This article explores how polyphony functions as a defining element of Taftī’s poetic practice, shaped by the theoretical framework of Mikhail Bakhtin’s dialogism and the cultural-linguistic experimentation of post-revolutionary Iranian literature.

The article unfolds across three sections. The first section, Rawyā Taftī and Postmodern Persian Poetry, situates her work within the broader aesthetic, cultural, and sociohistorical currents of the 1370s/1990s. It identifies the extratextual and intratextual forces, such as the postwar sociopolitical shift, the rise of a new middle class, and the influx of poststructuralist theory, that gave rise to a new poetic ethos marked by fragmentation, linguistic play, and pluralism. It also outlines the core stylistic features of this postmodern poetic paradigm, including the rejection of conventional narrative, the embrace of “linguality,” and the emergence of polyphony as a structural principle. The second section, The Limits of Current Scholarship, reviews existing literature on contemporary Iranian poetry and highlights the lack of focused analytical work on polyphony in Taftī’s oeuvre. While scholars have noted the presence of polyphony in the work of Barāhanī and other language poets, Taftī’s contribution to this mode of writing remains underexplored. This section thus establishes the necessity and originality of the present study. The third and central section, Polyphony: From Bakhtin to Iranian Postmodern Poetry, provides a detailed theoretical and textual analysis of polyphony in Taftī’s work. Divided into two main subsections, it first addresses dialogism, examining how Taftī crafts a multiplicity of voices through structural and stylistic devices such as hyphens, parentheses, punctuation, visual layout, and shifting narrative perspectives. These voices, ranging from human to nonhuman, internal to external, interact dialogically without collapsing into a unified authorial perspective. The second subsection focuses on intertextuality as a mode of polyphony, analyzing how Taftī incorporates and recontextualizes religious texts, especially the Quran, as well as classical literature, contemporary theory, and popular culture. Through citation, allusion, and parody, she produces a poetic space where diverse cultural registers coexist, often in tension or contradiction. By foregrounding these strategies, the article demonstrates that polyphony in Rawyā Taftī’s poetry is not merely a formal innovation but a deeply conceptual approach to language and meaning, one that reimagines the role of the poet, destabilizes narrative authority, and reflects the fractured realities of modern Iranian experience.

- Rawyā Taftī and Postmodern Persian Poetry

Rawyā Taftī is recognized as one of the prominent poets of the 1370s/1990s. She first gained literary acclaim with her poetry collection Sāyah lā-yi pūst (Shadow beneath the skin) (1376/1997), and subsequently continued her creative trajectory with Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand (My veins pass over my blouse) (1383/2004), Safar bih intihā-yi par (Journey to the end of feather) (1391/2012), Iqlīm-i dāgh (The burning clime) (1398/2019), and Infirādī-i dunyā (The world’s solitary) (1401/2022). Both she and her late husband, Shams Āqājānī, were distinguished students of Rizā Barāhanī and his literary circle. Consequently, Barāhanī’s linguistic innovations and stylistic influences are readily discernible in her poetic oeuvre.

The poetry and literary criticism of the 1370s/1990s are clearly distinguishable from those of the preceding decades in terms of intellectual orientation, theoretical frameworks, and structure. In this period, we encounter a significant number of poets who possess distinct voices and stylistic features, some of which are without precedent in earlier classical or modern Persian poetry.1Bihzād Khvājāt, Munāziʿah dar pīrhan: Bāzʹkhvānī-i shiʿr-i dahah-ʾi haftād [Conflict in clothes: Rereading the poetry of the nineties] (Ahvaz: Rasish, 1381/2002), 91. Broadly speaking, two major categories of influence, “intratextual” and “extratextual,” can be identified as shaping these stylistic transformations.2Bahrām Miqdādī, Farhang-i istilāhāt-i adabī az Aflātūn tā ʿasr-i hāzir [Dictionary of literary criticism terms from Plato to the contemporary age] (Tehran: Fikr-i Rūz, 1378/1999), 321. Among the extratextual factors, political and social developments stand out as particularly impactful in driving stylistic shifts across the periods.3ʿAlī Muhammadī, “Barrasī-i tahavvul-i dīd va sabk-i shiʿri-i Sāyah az rumāntīsm-i fardī bih rumāntīsm-i ijtimāʾī” [A study of the changes in perspective and poetic style of Sāyah from an individual romanticism to a social romanticism], Faslʹnāmah Takhassusī-i Sabkʹshināsī-i Nazm va Nasr-i Fārsī (Bahār-i Adab) 4, no. 1 (Spring 1390/2011), 222. One of the most consequential events of the 1370s/1990s was the relative peace that followed the Iran-Iraq War. As the wartime atmosphere of the 1360s/1980s began to dissipate, Iranian society underwent significant sociocultural change. A newly emerging urban middle class, characterized by its own set of values and worldviews, played a formative role in shaping the cultural and intellectual landscape of the time. Another critical factor influencing literary production during this decade was the proliferation of translations and original works on literary and cultural theory. Among these, Bābak Ahmadī’s Sākhtār va taʾvīl-i matn (Structure and interpretation of the text) exerted a considerable impact on both poetry and literary criticism.4Ismāʿīl Shafaq and Balāl Bahrānī, “Jarayān-i shiʿr-i zabān dar dahah-ʾi haftād, bā taʾkīd bar shiʿr-i Rizā Barāhanī” [Language poetry movement in the 1990s, with an emphasis on the poetry of Rizā Barāhanī], Shiʿrʹpazhūhī 11, no. 2 (Summer 1398/2019), 142. While the influence of existentialist thought, prominent in the literary circles of the 1350s/1960s and 1360s/1970s gradually waned, the translation of the works by thinkers such as Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, and Paul Ricœur ushered in a new intellectual paradigm. These translations catalyzed a shift toward postmodernist discourse.5Khvājāt, Munāziʿah dar pīrhan, 92.

Following the emergence of postmodern manifestations in society and the influence of extratextual factors on literary style, intratextual elements also began to assert themselves, resulting in a proliferation of diverse poetic voices. For example, Rizā Barāhanī introduced what is termed “Postmodern poetry,” ʿAlī Bābāchāhī conceptualized “Post-Nīmā poetry,” and Akbar Iksīr labeled his poetry “Beyond Modern.” Despite their differences, these trends can collectively be situated under the umbrella term “Postmodern poetry.” This is a form of poetry that eludes fixed meaning, resists traditional structure and narrative,6Qudratullāh Tāhirī, “Pustmudirnīsm va shiʿr-i muʿāsir-i Īrān” [Postmodernism and the Iranian contemporary poetry], Pazhūhishʹhā-yi Adabī 2, no. 8 (Summer 1384/2005), 48. and develops its own design and characteristics. In this poetic paradigm, inspired in part by Michel Foucault, the poet neither critiques dominant power structures nor defends the ideals of the masses.7Edward Said, Representations of the Intellectual, trans. Hamīd ʿAzdānlū (Tehran: Āmūzish, 1377/1998), 13. Instead, “form and language acquire new significance, while coherence, meaning, and meta-narratives are subjected to destruction.”8Tāhirī, “Pustmudirnīsm va shiʿr-i muʿāsir-i Īrān,” 32.

The most salient stylistic features of the poetry of the 1370s/1990s can be outlined as follows: (1) Poets of this period relinquished romantic, epic, and mystical language and expression, and instead, developed an intimate tone and diction to explore various aspects of private life. (2) They avoided grand concepts derived from intellectual and political systems, choosing instead to view the world as a continuous chain and to embrace the multidimensionality of all the truth and fact. (3) Their poetry was marked by polyphony and pluralism. (4) Traditional forms of imagination (simile, metaphor, metonymy, etc.) collapsed and dissolved throughout their poems.9Khvājāt, Munāziʿah dar pīrhan, 112–13. In fact, the poetry of the 1360s/1990s distanced itself from conventional literariness, often appearing raw, lacking in overt imagery and more aligned with popular taste.10Khvājāt, Munāziʿah dar pīrhan, 94. (5) Poets demonstrated a sharp desire to escape tame, ornamental language and showed a persistent curiosity toward uncovering the expressive potential of language, often approaching colloquial forms. For these poets, poetic language was no longer perceived as ostentatious and intimidating. Postmodern thinkers emphasized that language has no external referent, asserting that “poetry, the absolute monarch of linguistic performance, serves nothing but itself.”11Rizā Barāhanī, Khatāb bih parvānahʹhā [Address to butterflies] (Tehran: Markaz, 1374/1985), 115. Language, viewed as a tool for amusement, is reduced to a kind of “linguistic game,”12Barāhanī, Khatāb bih parvānahʹhā, 128. which became a central concern for the poets of the 1370s/1990s,13Khvājāt, Munāziʿah dar pīrhan, 97. especially those associated with the Barāhanī circle. (6) Poetry was composed with a sense of spontaneity, allowing conclusions and internal logic to emerge through the writing process itself, often incorporating techniques from other arts such as modern fiction, avant-garde theater, and modern cinema. (7) Poets rejected semantic and formal embellishment. (8) They boldly sought out new aesthetic and intellectual horizons, paying attention to forgotten or overlooked perspectives. (9) Their poetry was marked by striking simplicity formal poetry. (10) They introduced new, diverse, and flexible structures, making it difficult to clearly define the stylistic boundaries of this poetic movement. (11) A distinctive feature of their work was the use of dark and nervous humor.14Khvājāt, Munāziʿah dar pīrhan, 112 and 113.

As previously noted, Rawyā Taftī is among the group of poets who followed Rizā Barāhanī and were associated with the “Language Poetry Movement,” one of the most influential poetic movements of the 1370s/1990s. This movement positions itself in opposition to traditional poetic forms by adopting a distinctly linguistic approach, placing emphasis on the concept of “linguality” (zabāniyat). Within this framework, the poet’s primary function is understood as “expressing the language itself,” rather than conveying external themes or subject matter. One of the key manifestations of Barāhanī’s theory of linguality is polyphony. Parts three and four of this article will be devoted to an in-depth examination of the element of polyphony in Rawyā Taftī’s poetry. Before proceeding to this analysis, however, it is necessary to outline the rationale for the present study by addressing a significant gap in existing scholarship, namely, the absence of focused research on the manifestation of polyphony in Taftī’s work.

- The Limits of Current Scholarship

No independent research has been conducted specifically on the subject of the present article. However, there are a few studies that are indirectly related to the subject. Qudrat Allāh Tāhirī, in his article “Pustmudirnīsm va shiʿr-i muʿāsir-i Īrān” (Postmodernism and the Iranian contemporary poetry), categorizes Rawyā Taftī among Iranian postmodern poets.15Tāhirī, “Pustmudirnīsm va shiʿr-i muʿāsir-i Īrān,” 36. However, in his analysis of various elements found in the poems of these poets, he does not address the element of polyphony. Paymān Sultānī, in “Pulīfūnī dar shiʿr-i Barāhanī” (Polyphony in Barāhanī’s poetry), examines the role of polyphony in in Barāhanī’s work and argues that, from this perspective, his poetry surpasses that of T. S. Eliot and E. E. Cummings. In his analysis of the poem “Nigāh-i charkhān” (Rotating look), he writes: “Elements of combining voices… make the poem polyphonic by crossing the narratives from each other, cutting the voices, simultaneity, and so on. These combinations of voices do not follow each other or move in parallel; in fact, from the middle of the first voice, another voice starts to develop.”16Paymān Sultānī, “Pulīfūnī dar shiʿr-i Barāhanī” [Polyphony in Barāhanī’s poetry], Bāyā 8 and 9 (Ābān va Āzar 1378/ November and December 1999), 106. Ismāʿīl Shafaq and Balāl Bahrānī, in their article “Jarayān-i shiʿr-i zabān dar dahah-ʾi haftād, bā taʾkīd bar shiʿr-i Rizā Barāhanī” (Language poetry movement in the 1990s, with an emphasis on the poetry of Rizā Barāhanī), identify polyphony as “one of the main elements of language poetry.” However, they do not provide examples, and the conception is mentioned only as one of the linguistic features of Barāhanī’s poetry.17Shafaq and Bahrānī, “Jaryān-i shiʿr-i zabān,” 152. In summary, while existing scholarship has addressed the concept of polyphony in contemporary Iranian poetry, particularly in relation to Rizā Barāhanī, none has undertaken a focused analysis of polyphony in the work of Rawyā Taftī. The limited attention to this concept, either through general categorization without detailed exploration (as in Tāhirī), or through isolated discussions centered on other poets (as in Sultānī, Shafaq, and Bahrānī), highlights a clear gap in the literature. The present study seeks to fill this gap by offering a detailed examination of the role of polyphony in Taftī’s poetry, thereby contributing to a deeper understanding of both her individual poetics and the broader dynamics of the Language Poetry Movement in Iran.

- Polyphony: From Bakhtin to Iranian Postmodern Poetry

Polyphony, a term originally associated with music, derives from the Greek polus (meaning “many”) and phōnē (meaning “sound” or “voice”). In literary theory, it refers to a form of discourse in which multiple voices are heard simultaneously.18Zhālah Kahnamūypūr, “Chandʹāvāʾī dar mutūn-i dāstānī” [Polyphony in fiction], Pazhūhish-i Adabiyāt-i Muʿāsir-i Jahān 9 (Spring 1383/2004), 2. It was Mikhail Bakhtin who first introduced the concept into literary studies, particularly in relation to the novel, using it to describe the narrative structure of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s fiction.19Bābak Ahmadī, Sākhtār va taʾvīl-i matn [Structure and interpretation of the text] (Tehran: Markaz, 1387/2008), 99. Bakhtin argued that language operates within a network shaped by two opposing forces: centripetal (which seek unity and order) and centrifugal (which promote multiplicity and diversity. Polyphony, in his view, emerges when the centrifugal forces prevail, allowing for a dynamic interaction among diverse social, ideological, and linguistic discourses within the text.20Mikhail Bakhtin, Zībāʾīʹshināsī va nazariyah-ʾi rumān [Aesthetics and the theory of novel], translated by Āzīn Husayn′zādah (Tehran: Markaz-i Mutaliʿāt va Tahqīqāt-i Hunarī), 90. According to Bakhtin, certain literary texts are characterized by the simultaneous presence of multiple voices, none of which dominates or passes judgment on the others.21Oswald Ducrot, Le dire et le dit (Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 1984), 171. In such texts, each voice is granted equal value and autonomy, and no single perspective overrides the rests. Polyphony, therefore, “means the equal distribution of voices within a text, where all the voices have the right to coexist,”22Bahman Nāmvar Mutlaq, “Bakhtīn, guftugūmandī va chandʹsidāʾī, mutāliʿah-i pishāʹbaynāʹmatniyat-i Bakhtīnī” [Bakhtin, dialogism and polyphony, a study of Bakhtinian preintertextuality], Pazhūhishʹnāmah-yi ʿUlūm-i Insānī 57 (Spring 1387/2008), 399. and that is an arrangement grounded in the acceptance of the other. Tzvetan Todorov emphasizes that, for Bakhtin, this recognition of the other and the dialogic interaction among voices is the central feature of polyphony.23Tzvetan Todorov, “Bakhtine et l’altérité,” Poétique 40 (1979): 502–13.

In Bakhtin’s theory, polyphony is primarily a feature of prose rather than poetry. “Poetic complexity, Bakhtin would say, locates itself between the discourse and the world; that of prose, between the same discourse and its utterers. [Therefore,] it isn’t that the representation of discourse, and therefore of its utterer, is impossible in poetry, but it just isn’t aesthetically valorized there as it is in prose.”24Tzvetan Todorov, Mikhail Bakhtin: The Dialogical Principle (University of Minnesota Press, 1984), 64. This is because “the poet is limited by the thought of a unique language, a single utterance which is finalized on self-expression.”25Mikhail Bakhtine, Esthétique et théorie du roman (Paris: Gallimard, 1975), 117.

Nevertheless, polyphony is regarded as one of the central features of Iranian postmodern poetry. In fact, Barāhanī argues that one of the fundamental shortcomings of Nīmā Yūshīj’s poetry is its “monophonic” nature.26Barāhanī, Khatāb bih parvānahʹhā, 137. The tendency of 1370s/1990s poetry to avoid overarching generalizations is tied to the decline of grand political theories, such as those related to revolution. During this period, Iranian society shifted from a revolutionary framework to one of reform and gradual restoration, which is a strategy marked by moderation. This broader cultural and political moderation is reflected in poetic language as well. Poets begin to craft polyphonic poems that allowed for the expression of diverse and even paradoxical voices within a single poetic space.27Khvājāt, Munāziʿah dar pīrhan, 92 and 32. This shift is evident in the poetry Rawyā Taftī, a poet who explicitly rejects singularity of voice. In her poem “Zadahʹam” (I’m weary), she writes: “I’m tired of monologue and the cemetery of silence,” directly articulating her resistance to monologic expression.28Rawyā Taftī, Iqlīm-i dāgh [Hot climate] (Tehran: Māniyā-yi Hunar, 1397/2018), 65.

3.1. Dialogism

Dialogism is a foundational concept in Bakhtin’s theory of textual and intertextual relations. Central to his thought is the idea that individual consciousness, and by extension, literary voice, is shaped through interaction with others in a social context. Bakhtin placed strong emphasis on the role of society in the formation of human character, and he argued that language is the medium through which dialogism is most vividly realized. For Bakhtin, discourse is never isolated; it is always in dialogue with other discourses.29Nāmvar Mutlaq, “Bakhtīn, guftugūmandī,” 400. Therefore, there is a close and intrinsic relationship between dialogism and polyphony. One might even argue that polyphony is a characteristic or a specific manifestation of dialogism, or more precisely, that “polyphony in which all the voices are reflected equally results in dialogism.”30Tiphaine Samoyault, L’intertextualité (Paris: Armand Colin, 2005), 11. Both of these elements—dialogism and polyphony—can be readily identified in the poetry of Rawyā Taftī, where they appear in both subtle and explicit forms. A striking example occurs in her poem “Dū-tā hastand” (They are two), in which dialogism functions as the central mechanism of polyphony. The poem presents three distinct voices. The first is the narrator’s, who states: “There’s someone who walks over himself every morning, sticks on a smile… and punches card.”31Rawyā Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst [Shadow under the skin] (Tehran: Būtīmār, 1394/2015), 16. This internal voice is then juxtaposed with two external voices:

– Good morning.

– Madam, you’re late again.

– I went to buy eyes and I passed the toll booth too.32Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 16.

The poet shows this dialogism using a punctuation mark, the hyphen (-). As is well known, one of the conventional functions of the hyphen in literature is to indicate dialogue in prose, especially in novels and plays. In the poem, the hyphen serves precisely this purpose, marking the shifts between multiple voices. One of these voices appears to belong to a supervisor reprimanding an employee, while the other represents an individual who, based on context, seems habitually late. In Bakhtinian dialogism, response holds a certain primacy as the initiating and motivating force within the dialogic exchange. In fact, it is the response that generates the conditions for understanding—an understanding that is neither passive nor stative, but dynamic and active. As Bakhtin asserts, genuine understanding can only be achieved through response, and the relationship between understanding and response dialectical, with each shaping and informing each other.33Mikhail Bakhtin, Takhayyul-i mukalimahʾī [The dialogic imagination], trans. Rawyā Pūrāzar (Tehran: Nay, 1387/2008), 371. Moreover, the way poets of the 1370s/1990s conceptualize the human subject diverges from earlier traditions. In the poetry of the previous decades, individuals often appeared as “stereotypes” rather than fully realized “characters,” their actions and emotions imbued with mythological or at least symbolic resonance. In contrast, 1370s/1990s poetry presents a more grounded, quotidian view of humanity. The once unattainable or idealized human figure is now rendered as an ordinary passerby on the street. If necessary, the poet may even depict someone who is “very good” but casually picks their nose or play cruel tricks on workers. This shift from ideal to flawed, from celestial to mundane, marks the metaphorical descent of the human figure “from heaven to earth,” in which everyday gestures and banalities acquire a new kind of mythological significance.34Khvājāt, Munāziʿah dar pīrhan, 94–95.

In the second part of “Dū-tā hastand,” this polyphonic structure continues. The narrator states: “There’s someone who makes two open eyes red every day.” Other voices emerge again:

– Madam, this job comes with responsibilities.

– I’m careful, he doesn’t like burned eye.

There’s someone who, every day, even as they pass the toll booth, the walls rise.

– Madam, this job requires focus.35Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 16.

This dialogism extends to the conclusion of the poem and is further exemplified in piece by Taftī titled “Guftugū” (Conversation). In this poem, dialogic structure is once again foregrounded with the hyphen, which marks exchanges between the narrator and an implied interlocutor. However, a third voice—the voice of the poet herself—also emerges, framed parenthetically. This structural layering results in a complex interplay between distinct yet interconnected perspectives, further emphasizing the poem’s polyphonic quality. The textual performance of “Guftugū” is marked by fragmentation, ellipsis, and syntactic disjunction, which resist linear meaning and reinforce the instability of identity and address. The speaker opens with an existential question:

To what degree I should stay near zero? My newest dress more torn up

The hyphen introduces the voice of another:

– Will you come undone from yourself?

What follows is a cascade of overlapping utterances:

I’ll come undone from you, too if you become a place that’s out of place

I’ll settle in every place when you become placeless in a place

I’ll find a place instantly I’ll become without… in place

without… without… without…

The dialogic mode here is not one of clarity or resolution, but of unraveling and recursion, where voices interrupt, contradict, and bleed into one another. A third speaker cuts in:

– You talk too much!

The original voice responds:

If I stay silent my voice grows hoarse,

Long stretches my head—tell me, is the one who fears more poet than white or the one who spills and resembles black?

– The hands are small or else I’d notice the details.

Parentheses introduce a self-reflexive voice, presumed to be the poet’s inner monologue or meta-commentary:

(What if my dream isn’t wrong and that part isn’t round?

I walk with my hands so the temple remains untouched

To what degree should I stay zero?

I wear a matchstick.)

Here, the poet seems to question the structure of both dream and language, destabilizing the boundaries between speaker and self. The poem concludes with lines that further fracture subjectivity and voice:

Line me up, line me up, nobody knows turns

They stay black in clusters

O n e b y o n e, white

– split ends are more poet

(Where’s farther than you?)

Give me my glove. 36Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 36–37.

The poem “Ihyānan” (Probably) opens with the phrase “By the way,” as though it is situated in the midst of an ongoing conversation or is itself a fragment of a dialogue. This opening evokes a narrative technique reminiscent of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, which similarly begins in media res. The opening lines of the poem—“By the way, I’m not a genius to die early / Seven boundless borders pass quickly / and you, who can actually reach your hands further / and the owls on your shoulder…”37Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 25.—suggest an ongoing conversation that precedes the poem’s commencement. If we consider narrative as a carrier of a message from the sender to the receiver, which happens verbally,38Shlomith Rimmon-Kenan, Narrative Fiction: Contemporary Poetics, trans. Abulfazl Hurrī (Tehran: Nilūfar, 1401/2022), 24. the phrase “by the way” implies that the message of this poem is being relayed rather unexpectedly, and that the narrator is continuing a conversation already in progress. This method is discussed in studies in the field of narratology. Key works such as Gregory Currie’s Narratives and Narrators: A Philosophy of Stories, Martin McQuillan’s The Narrative Reader, and Gerald Prince’s Narratology all explore these dynamics of narrative structure and discourse.39Gregory Currie, Narratives and Narrators: A Philosophy of Stories (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010); Martin McQuillan, The Narrative Reader (London: Routledge, 2000); Gerald Prince, Narratology: The Form and Functioning of Narrative (Berlin: Mouton, 1982).

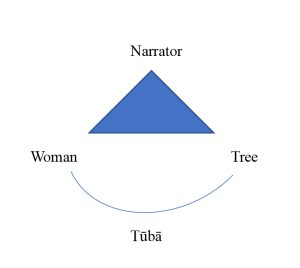

In the opening of the poem “Tūbā-yi nāʹtamām” (Unfinished Tūbā), the narrator seems to be engaged in a conversation with a woman named Tūbā, addressing her as “My Tūbā of a thousand branches, Tūbā!”40Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 18. This creates the impression of entering into a dialogue with someone named Tūbā. However, the repetition of “Tūbā” raises the question: Is this truly the name of a real woman, or simply a way to underscore the poet’s self-comparison to the Tūbā tree in this line? Or perhaps both interpretations coexist? The narrator’s narrative choice presents an interesting tension—whether to describe Tūbā from an external vantage point, as an impartial observer, or from more subjective, internalized perspective.41Gerald Prince, Narratology: The Form and Functioning of Narrative, trans. Muhammad Shahbā (Tehran: Mīnū-yi Khirad, 1391/2012), 54. The poem allows for both possibilities, creating a fluid narrative atmosphere. Essentially, “in a successful polyphonic poem, the point of generation takes shape in the conflict between multiple truths.”42Khvājāt, Munāziʿah dar pīrhan, 105. According to this, the image below can represent the three distinct voices: the narrator, the woman and the tree.

As the poem progresses, it becomes clear that Tūbā is used as a woman’s name, as demonstrated in the lines: “There’s only one way / I share your milk only with myself / I suck at your round leaves, sumac / My hands and eyes on your breast.”43Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 18. In these stanzas, Tūbā is simultaneously portrayed as a woman who provides milk and as a tree whose round leaves are drawn upon by the narrator. The imagery and descriptions in the subsequent stanzas further affirm that Tūbā is conceptualized as a woman:

Tūbā! You’re the lady of melted snows

Put both your breasts in my mouth

Will you share love?…

However, Tūbā is later depicted as a tree whose nameless branches might be infused with pepper:

Tell me that your highest branch is not saturated with pepper

I consume the final sunshine entirely for you

Unfinished Tūbā

And put that nameless branch in my mouth!44Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 18–19.

In “ʿIshq va kūtāhī va marg” (Love and shortness and death), we encounter a layered and fragmented conversation between the narrator, the poet (addressing Rawyā, the poet’s name), God, and a nurse:

…I created poetry out of suffering / Had you ever witnessed the suffering you yourself created? / They use onions excessively, even as mere seasoning / You created humans, even if only for seasoning / Even for seasoning / Look, Rawyā / Like the last water given to an animal … / You created humans at the doorway / A frame can be drawn around it, then one can depart… / The nurse said: “Admonish him even once! He, too, will recognize you…” / You should respect my privacy… / I say you, too are responsible / And I will not turn my face away…45Taftī, Iqlīm-i dāgh, 36–38.

In “Andar hikāyat-i kharīd-i yik bāb manzil-i maskūnī” (The story of buying a residential house), the conversation of the characters is rendered with clarity, highlighted through the use hyphens to distinguish direct speech:

Farībā says: I see the homeless here reading for hours / facing toward the corner of the sea / They must have no rainy days there.

The books wink at me again

– Caress our spines or at least don’t raise so much dust!

– Caress!…

– Who won!

– Who lost?

– Who lost?

– Who won?46Rawyā Taftī, Safar bih intihā-yi par [Journey to the end of feather] (Tehran: Būtimār, 1391/2012), 112.

In “Sarāb” (Mirage), dialogism is presented through a minimalistic and fragmented exchange, where the conversation is marked by colons:

He said: OK I said: OK

He said: Let’s go I said: OK

He said: You don’t have I said: Sincerity

He said… He said… He said

I didn’t say… I didn’t say… He said.47Taftī, Safar bih intihā-yi par, 124.

However, as previously discussed, one of the distinct voices in these poems emerges through the parenthetical remarks inserted by the poet. These asides represent a layer of voice that exists beyond those present within the main body of the text, particularly beyond that of the narrator. If it were the voice of the narrator, there would be no structural need for the parentheses. Their use signals a separate, reflexive, and perhaps meta-poetic voice. For example, in “Ihyānan” (Probably), we read:

… a monotonous rhythm / a monotonous rhythm / a monotonous rhythm and accidentally decisive (like games without goals) / ask don’t be ashamed from me… / …I forgot / I forgot / You violate my poem once in a while (before I write a poem, I should have tea) / and you who can actually reach further with your hands….48Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 25–26.

Also, in “Az qalam uftādah” (Left out) we read:

Do I know how to knot? / First, let me see what things have been deliberately left out (in the newspapers) today / Of course, there’s always the emphasis: what should I do about lunch? (God willing, he is in his growth years) … / Well, not the burglar alarm / not Mullā Sadrā restaurant / but you can’t stay behind people’s door either (especially if you get cancer).49Rawyā Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand [My veins pass over my blouse] (Tehran:Vīstār, 1383/2004), 18–19.

Or in “Dubāʾī”:

Can they avoid running over the street children? / Or not turn around? (Like this poem that keeps reducing the distance from slogans and / has a sharp, difficult border / What mischief a little child can get up to!).50Taftī, Safar bih intihā-yi par, 28.

The poet asserts her presence not only in the body of the poem but also in the footnotes. In one such note, she writes, “Like (the letter) alif (ا), which, when placed between (the letters) ʿayn (ع) and rā (ر), transforms (the word) شعر (poetry) into (the word) شعار (slogan).”51Taftī, Safar bih intihā-yi par, 28.

In the poem “Taqdīm bih nām-i khānivādigī” (Dedicated to the family name), we hear a polyphonic interplay of voices—the narrator, the poet and the character of the poem offering reflection and advice:

I’m dancing with grace / While watching him / He’s growing, that much is clear obviously/ It’s me who changes and bends / Can life be more standard than this? (What a fluent rhythm this word has!).52Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 38.

Amidst this, the character’s advisory voice interjects:

For every action, there is a reaction in reverse

– Useless lessons.53Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 39.

In the poem “Nakun” (Don’t), three distinct rebellious and questioning voices—the daughter, the woman, and the mother—are heard, each marked by different punctuation styles to signify their individuality:

– Don’t

: Don’t

(Don’t)

Shouldn’t I have become a girl?54Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 14.

In this poem, the word “don’t” is repeated three time, each instance marked by a different punctuation mark. Taftī uses these shifts in punctuation not only to reflect variation in tone and speaker but also to distinguish between multiple narrative perspectives. The parenthesis signals the poet’s self-assertion into the text, while the hyphen and colon indicate the conversational exchanges among different characters. At the poem’s conclusion, the voice of a questioning girl emerges. This structural pattern continues through the shifting placement of punctuation marks:

(Don’t)

: Don’t

– Don’t

Shouldn’t I have become a woman?55Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 14.

In contrast, the voice of the questioning mother appears only once and is enclosed in square brackets—as though it is an appended or peripheral voice rather than one fully integrated into the central narrative:

[Don’t]

Why did I become a mother?56Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 14–15.

This method of using punctuation marks such as parentheses, colons, and dashes) as tools of characterization and structural layering recurs in several of Taftī’s poems, including “Harāj”57Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 22. (Sale), “Pāytakht”58Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 58. (Capital) and “Az qalam uftādah”59Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 18–19. (Left out). Beyond the explicitly marked voices, Taftī sometimes embeds subtler, implicit voices that demand close reading and interpretation. These voices are not always signaled by punctuation. For example, in the poem “Band” (Thread), we hear the voices of the narrator, a man, a woman, and a doctor:

– Sir, I want something like clothes

– Madam! Kill me and make me beautiful for this and that’s it

– Doctor! Make my yawning attractive

I desire a heart / I desire it to turn into kebab in no time…60Taftī, Iqlīm-i dāgh, 89.

Through these polyphonic and punctuated structures, Taftī constructs a poetic space in which the boundaries between speaker, character, and authorial voice are blurred. Punctuation, in her work, becomes more than a syntactical device. It is a formal strategy for voicing, layering, and dislocating narrative authority. The poem presents a cacophony of voices, interweaving elements from both traditional and modern discourses. On one hand, the poem draws from classical references such as prophetic tradition or hadith, a New Year prayer, divine wisdom or hikmat, proverb, and even symbolic imagery like the Great Wall of China. On the other hand, it incorporates the language of consumer culture and pop aesthetics—embryo porridge, decoupage, epilation, tattoo, fashion, Madonna, among others:

Embryo porridge performs miracles / It’s the raw material for reliable cream powders / It’s excellent for dry and oily skins / I won’t open my mouth / It reeks and travels far / Seek knowledge even if it is in China / Seek knowledge even from the embryo / Seek knowledge even my skirt is pleated / The wall around me pleated China / He left and the pleat reached this far / I should know this / Decoupage Highlight Champagne mesh Epilation Face mask / mask Eyebrows Tattoo This cream temporarily masks the lips / I pull my skin like this / Peeling and lasering… / Khalījī make-up Arab Madonna / I need to start / Anyway, if you look closely, it needs surgery / I start / from the tip of my nose to / my “A word that comes from the heart, inevitably settles in the heart.” / I will have an operation on my bewilderment, too… / I pray if you’d come this time / White is in fashion / and thank God, His hand still rests on wisdom… / Suppose there’s something wrong with this job / Then O, You, Changer of states / Deliver us from this impermanence….61Taftī, Iqlīm-i dāgh, 87–90.

One of the defining features of dialogism in Taftī’s poetry is the presence of parallel and intersecting voices, each occupying its own narrative and tonal space within a shared poetic structure. For instance, in “Safarʹnāmah-ʾi yik rūzʹnāmah” (Travelogue of a newspaper), the poem unfolds through multiple distinct voices, each introduced by a numbered heading. These voices are situated across various social and physical contexts:

-

- I’m easily available in this familiar comedy; 2. Next to the hands of a young woman; 3. At the local greengrocer’s; 4. On the desk of a man who is busier than he should be; 5. Hand in hand with a worker bent to become aaah and clean the windows of a tower in Saʿadatabad; 6. In the swarm of the students’ special dormitory.62Taftī, Safar bih intihā-yi par, 56.

This polyphonic layering is also evident in “Khvudʹnivisht” (Autography), where the speaker’s identity emerges through the interplay of familial, social, and self-assigned labels:

I’m a female… / My mother says: You’re obstinate / My father says: You’re ruined in this world and the next / You say: I’m romantic / He says: / You’re sick! / My friends say: Kind! / … My son says: Well done!63Taftī, Iqlīm-i dāgh, 8.

Here, dialogism functions as a mechanism of self-construction, where identity is not singular but constantly negotiated among competing voices.

In “Kun fa-yakūn” (Be and it is), the dialogic structure becomes explicitly metaphysical, staging a conversation between the narrator and God parallel. Their voices appear in alternating lines, collapsing ontological and poetic registers:

Narrator: “The start is no end / God thinks more again”

God: “Should I say ‘Be, and it is’? I’ll say it”

Narrator: “It’s God, after all! He melted the clay and poured it.”

God: “Was there anyone? Is there anyone? Is there no one?”

Narrator: “My emptiness, bead by bead, onto a string, so maybe it becomes a charm/ Your hands / Did it?”

God: “I flowered. I flowered so your being could be.”

Narrator: “You said ‘be’ again / a thread between my hand and your scent that I’m torn up / only the number of your picture in the frame of lest.64Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 9.

In the poem “Barʹgardān bih khvudam” (Return to myself), the dialogic structure unfolds through the simultaneous presence of three voices of the narrator, a nurse, and doctor. These voices emerge in parallel:

… I’m not sure / Some parts of me haven’t grown bigger! /

– This is an abnormality!

A doctor loudly proclaims that I need surgery

A nurse loudly proclaims that I have no experience

I make it louder: This is a historical abnormality…65Taftī, Safar bih intihā-yi par, 28.

In Taftī’s postmodern poetic world, dialogism is extended beyond human characters to include objects and non-human voices. For example, in “Man chāqū va chashm va chasb-i zakhmī kih rū-yi zabān” (I, knife and eye and band-aid on the tongue), a surreal polyphony emerges in which even inanimate objects speak. Amid a series of disjointed yet charged exchanges marked by hyphens and colons, the voice of a knife enters the conversation:

– Don’t cut!

Be careful!…

This knife is throwing itself into the mix, too / Little does it know that I’m full of infection from distant soils…

– All right! You’re full of “You do something!”

– You do something!

– Won’t you budge?

– So, you’re too directionless to penetrate

: You do something!66Taftī, Safar bih intihā-yi par, 68.

In Taftī’s poem “Dīvār” (Wall), the voice of an inanimate object, the wall, is brought to life:

…You changed with your tongue / instead I arranged a meeting with the wall / When it grows shorter / We’ll be even on both ends…67Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 92–93.

In “Va har chih kih nīst” (And whatever is not), the voices of the walls and alleys enter the simultaneously:

If you see an old woman pregnant, don’t be surprised sooner than me… / Walls, too, start laughing / and the alley’s waist hurts by the electric wires / to reach / the corner…68Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 75.

This characteristic reaches its a climatic expression in “Yik nafas” (One breath), where objects and natural elements take on a voice of their own:

…Where should I stand? / The room doesn’t know either… / How did this tree come from the rooftop? / Why does it hesitate to give us its fruits / And the woods and stones that… / How patient! / I turn around to have a swim with a newspaper… / …The human’s fate, in essence, is left in the hands of poems that have been emptied of meaning / like the syncope of a train that spits out its passengers one by one / …and the train goes to multiply the closed windows on its path.69Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 94, 96–97.

Also, in “Sargījah” (Vertigo):

I wish my head would take a break / Stop spinning / The earth would stick, wet, to my waist / Stop spinning / And the culprit colors wouldn’t change places / And be tongue-tied.70Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 103.

This strategy is also evident in “Āftāb-i ʿufūnī” (Infected sun):

This pillow knows what I’m saying / An iron gate that remains open facing down / Maybe it will make the infected sun disappointed in me, but

Red? No

Black? No

When you bloom, green / My old pillow cries out / Nothing remains left to forget / The boss’s eyeballs are infertile / Parīsā’s engagement finger was caught in a press / She laughs: There’s a knuckle left / I should raise her blood pressure with something

Water… water… / It’s been memorized / Parīsā, the boss, and you… / Where on this whole hand should I put henna? / My old pillow cries out.71Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 107–8.

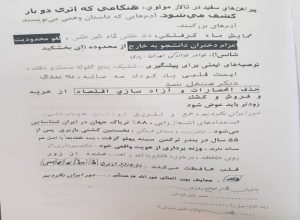

Another notable example of polyphonic poetry in Taftī’s oeuvre is the poem “Taqdīm bih nām-i khānivādigī” (Dedicated to the family name), in which, alongside the distinct voices of the narrator, the poet, and the adviser, a newspaper-like page is embedded in the poem.72Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 41. The formal insertion not only multiplies the discursive registers of the poem but also foregrounds the dialogic interplay between various narrative modes. As Rimmon-Kenan observes, “newspaper reports, history books, novels, films, comic strips, pantomime, dance, gossip, psychoanalytic sessions are only some of the narratives which permeate our lives.”73Shlomith Rimmon-Kenan, Narrative Fiction: Contemporary Poetics, trans. Abū al-Fazl Hurrī (Tehran: Nilūfar, 1401/2022), 24. The visual and structural gesture of incorporating a printed news format allows the poet to stage a confluence of disparate, overlapping, and parallel voices—serious, humorous, colloquial, ironic, and protest-driven—within a single poetic space. The image below further illustrates how the poem materializes this multiplicity through a simulated newspaper layout:

Figure1: Rawyā Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 75

White shirts in Mawlavī Hall, when a work is discovered twice. People who write fantasy fiction are great people.

Lunar Eclipse Conference, shouting publicly during private time, the lifting of the ban on sending female university students outside of the limit (Oh! Damn luck!), The Tehran–Paris Sisterhood.

Immunity guidelines for protection, shooting five light and gaudy bullets, a three-year-old child’s cardiac arrest, transferred to another ward

Elimination of monopolies and liberalization of the economy from buying and selling and curd

It should be changed sooner

We revolve around Iran (in devotion), addition and subtraction of street children, entrepreneurial talents, 88% of the world’s opium is identified in Iran. Interzert and cultural issues. The first cargo ship docked in Bandar Turkaman after 55 years is afflicted with pneumonia. (Three dot)s have an issue with the original as well. Weightlifting one’s own identity, photographing memory, a firm stance against revelry and indulgence, laughter strengthens the heart’s resilience. Earthquake from Tehran is CERTAIN. International Conference on Cultural Heritage…. We revolve around Iran (in devotion).

If even for five days, a gardener….

………….. the nightingale should wait

The world-blowing Rend…………..

…… should suffer when trapped.

Taftī uses elements of popular culture as another strategy for creating polyphony in her poetry. While modernists often distanced themselves from or denounced popular culture, postmodernists tend to incorporate it, allowing for the coexistence of high and low registers within the same textual space.74Sīrūs Shamīsā, Naqd-i adabī [Literary criticism] (4th repr. ed., Tehran: Firdaws, 1383/2004), 321. A clear example of this polyphonic engagement with popular culture appears in the poem “Khassah shudīm” (We’re tired), which mimics the rhythmic and repetitive structure of a nursery rhyme:

We are open, we are close / We are open, we are close / We are the knife, we are the handle / We are the plum, we are kernel / When it’s absent, we are tired / There’s dirt on our shoes / “Who’s bought one sock, nincompoop!” / Mama says: “Has anyone seen?” / Hey, will you play hide-and-seek with the one who isn’t there? / I say hide-and-seek / He says Atal Matal / He turns this way and that way / He sweeps the sky / Āchīn-u vāchīn / Pull up one of your legs.75Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 48–49.

Another of Taftī’s formal techniques for differentiating and multiplying voices is her use typographic variation and code-switching; for example, in the poem “Va kūdak ast hanūz” (And he’s still a child), the English word “Error” appears within an otherwise Persian text:

The painted women who smirk are my sisters / The digital women with fused anklets and torn eyelids- / When they “Eror” / All.76Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 45. All or Āl is also a subtle reference the mythical creature Āl that harms women after childbirth.

The intrusion of the foreign word visually and semantically disrupts the Persian flow, marking a rupture that signals another discursive register. Another example is linguistic hybridity and polyphonic layering appears in the poem “Harāj” (Auction), where Taftī incorporates the English word “chat” into an otherwise Persian linguistic field:

She immediately / lost her legs many times in the auction / Disoriented /: Will you feel faint again tonight? / -This manicure really goes with your underwear / She laughed, and they started to “chat.”77Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 22.

This technique recurs in other poems as well, such as “Taʿlīq” (Suspense),78Taftī, Safar bih intihā-yi par, 98. and “Andar hikāyat-i kharīd-i yik vāhid-i maskūnī” (The story of buying a residential house).79Taftī, Safar bih intihā-yi par, 112. In “Ādam-i barfī” (Snowman), the foreign word “monitor” (instead of its Persian equivalent) is phonetically transcribed into Persian, while the word “mail” appears in its original English script, foregrounding the visual and semantic rupture within the Persian text:

…. Until they reach… our personal monitor / War reports pass through it / Economy earthquake tsunami twister breeze flood / and the final kisses at the end of each “mail” / through this same path / the films of instruction and intimacy…80Taftī, Iqlīm-i dāgh, 74.

In “Tashkhīs muhimʹtar ast yā darmān” (Is diagnosis more important than treatment?), Taftī pushes this strategy further by embedding entire English sentences into the body of the poem word, rather than isolated words:

Some are gods of revelry / some gods of resolve / She, absorbed in the heat of her own dance, / asked: “Where are you from?” / My dehydration was due to the tears I had shed / my high blood pressure was due to the waters I hadn’t shed / He didn’t diagnose the molten ancestry / From the nose to the liver / Ablaze / From the hands to the waist / He said: “You seem abnormal!”81Taftī, Iqlīm-i dāgh, 21.

In the poem “Sih-i nīmahʹshab” (Three in the morning), a distinct form of this polyphonic layering appears in the simultaneous inclusion of Arabic and English sentences in a Persian-language poem, producing a multilingual texture and interwoven registers:

How much can one prolong waiting? / And yet, you were perfect beyond words / The mother tongue wasn’t enough / It came, it didn’t come and still wasn’t enough / Though the mother tongue was perfect / It uttered “Is there someone to help me?” [in Arabic] / “Can you help me?” [in English]82Taftī, Safar bih intihā-yi par, 84.

Another notable technique in Taftī’s work is the use of what might be called “visual voices.” This method of representing voice relies on a dramatized mode of composition, in which writing polyphonic poetry requires a performative and visually aware sensibility. The poet should allow her imagination to be shaped by various aesthetic registers in order to access the temporality or chronology of language. The approach presupposes an understanding that poetry is constructed not only from semantic content but also from auditory and graphic signs; that is, poetry resonates in sound before it delivers meaning.83Sultānī, “Pulīfūnī dar shiʿr-i Barāhanī,” 108. In this context, rather than transcribing a sound sign, the poet visually stages it. For example, in the poem “Hamīn jā bishkanam?” (Should I break it here?), the following lines demonstrate this visual dimension of voice: 84Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 64, 66.

Every day, like a capsule

At the exact time

And water drips over it / who thought / I had turned into an octopus, sticky

And time, in this manner, flows through me

(gulp) O O

O

… I cut meat and break sugar and snap my fingers

Should I break here?

They’re more suitable for passing

And our differences are these two gulps

Gulp O O

O O O

O

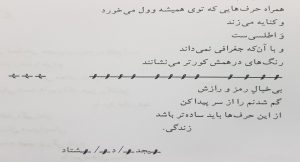

In the poem “Gar +” (If +),85Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 36. this technique of visual voicing is used once again:

Figure 2: Taftī, Ragʹhāyam az rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 36.

With words that always wiggle

And squib

And are an atlas

And while it doesn’t know geography

Its blended colors lie more blindly

[the picture]

Let go of its mysteries

Trace my lost self, starting from the head

It should be easier than this

Life.

[the picture]

The visual element also appears in the poem “Haftād va dū” (Seventy-two), where image and text intersect to extend the poem’s polyphonic form: 86Taftī, Safar bih intihā-yi par, 122.

… You went to the margins with my buts

The smell of bubbles came

For seventy-two hours

It still comes

O

Oo

0

0

0

There are several important considerations before concluding this section. First, another form of dialogism present in Rawyā Taftī’s poetry is the dialogue with the inner “I”s of the narrator-poet. These inner voices form challenging and subjective discourses, examples of which can be found in the excerpts discussed in this article. Another important polyphonic technique in Taftī’s poetry is the use of the “stream of consciousness,” which facilitates the layering of voices and the fragmentation of thought. This is exemplified in the following excerpts that have been discussed above:

… a monotonous rhythm / a monotonous rhythm / a monotonous rhythm and accidentally decisive (like games without goals) / ask don’t be ashamed from me… / …I forgot / I forgot / You violate my poem occasionally (before I write a poem, I should have tea) / and you who can actually reach further with your hands….87Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 25–26.

Lastly, it should be noted that while reading the poems under consideration, some of them may appear ambiguous and nonsensical. This characteristic was, in fact, one of the key challenges faced by readers of poetry of the 1370s/1990s, as many found it seemingly incoherent and difficult to follow. However, this apparent incoherence, which is also present in classical poetry, is not a flaw but rather a deliberate strategy. By presenting labyrinthine objects and spaces, the poem invites a more creative and personal engagement from the readers, who embark on a journey with their own identity cards. The poem is not constrained by the poet’s final words (as the poet of the 1370s/1990s is not concerned with finality). The polyphonic nature of this poetry frees the readers from what the poem may seem to dictate, allowing different images and expressions to create a network or a space in which both the poet and the readers, faced with a barrage of these concepts, might feel as though nothing is being said. In other words, the readers of this type of poetry should not insist on a fixed position. Rather, they should become inquisitive explorers, navigating the spaces between the lines. Is it not true that in real life, the last words remain hidden, and what matters is the attempt to find them?88Khvājāt, Munāziʿah dar pīrhan, 95, 112.

3.2. Intertextuality

Intertextuality is a concept in Bakhtin’s thought that signifies that each speech “is in dialogue with the speeches before it and the speeches after it with common topics. Therefore, each speech is influenced by a speech in the past and is a basis for a speech in the future.”89Kūrush Safarī, Farhang-i tawsīfī-i mutāliʿāt-i adabī [Descriptive dictionary of literary studies] (Tehran: ʿIlmī, 1395/2016), 487–88. Julia Kristeva later reformulated Mikhail Bakhtin’s ideas into the theory of intertextuality. She asserts that “intertextuality is based on the idea that a text is not a closed, independent and self-sufficient system; it has a mutual and close relation with other texts. It can be said that in a certain text, there are constant dialogues between that text and the texts that exist outside of it.”90Bahrām Miqdādī, Dānishʹnāmah-ʾi naqd-i adabī az Aflātūn tā bih imrūz [Encyclopedia of literary criticism from Plato to today] (Tehran: Chishmah, 1393/2014), 146. Similarly, Barthes argues that each text is a new texture made of old points and references. According to him, fragments of popular language and cultural reference enter the text and are scattered within it, because language is always walking in front of and around the text.91Irena Rima Makaryk, Encyclopedia of Contemporary Literary Theory: Approaches, Scholars, Terms, translated by Mihrān Muhājir and Muhammad Nabavī (Tehran: Āgah, 1393/2014), 72. One of the manifestations of polyphony is intertextuality, which can be clearly traced in Rawyā Taftī’s works.

The most prominent intertextual voice in Taftī’s poetry is the that of religion. From a postmodernist perspective, it is not necessary to confine oneself to the tools and affordances of the modernist age. Instead, one can reengage with the cultural and symbolic resources of earlier periods and renew them for contemporary expression. The modernist dismissal of religion altogether is, in the view of many postmodern thinkers, a limiting and ultimately unproductive gesture.92Shamīsā, Naqd-i adabī, 320. One of the voices marginalized during the modernist period is the voice of religion; yet, in postmodernist poetry, at least in Rawyā Taftī’s poems, this voice re-emerges with clarity and resonance. Among religious intertexts, the voice of the Quran is especially prominent. Taftī frequently incorporates Quranic phrases, verses, or fragments of verses in her poems. One such example is Tūbā, a Quranic term that refers to a tree in paradise, mentioned in Sūrah al-Raʿd, verse 29: “Those who believe and do good, for them will be bliss and an honorable destination.” According to religious narratives, Tūbā is a tree in paradise whose branches extend into every house, much like sunlight. Each branch bears fruits and blessings that have not been seen, heard or even imagined. It is said that God created this tree with His own hand and endowed it with life, so that the inhabitants of paradise may choose from it any blessing or fruit that they desire.93Ismāʿīl bin ʿUmar ibn Kasīr Damishqī, Tafsīr-i al-Qurān al-ʿAzīm [Commentary on the Great Quran], ed. Yūsuf Marʿashlī (3rd repr. ed., Beirut: Dār-ul-Maʿrifah, 1409/1988), 392.

In the poem “Kun fayakūn” (Be, and it is), the poet poses the question: “Should I say ‘Be and it is’? I’ll say it.”94Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 8. The phrase kun fayakūn is a well-known Quranic expression signifying divine creative command. It appears in several Quranic chapters, including Sūrah al-Baqarah (2:117), which states: “He is the Originator of the heavens and the earth! When He decrees a matter, He simply tells it, ‘Be!’ and it is!” Other instances can be found in Sūrah Āl-i ʿImrān (3:47, 3:59), Sūrah al-Nakhl (16:40), Sūrah Al-Anʿām (6:73), Sūrah Maryam (19:35), Sūrah Yāsīn (36:82) and Sūrah al-Ghāfir (40:68). Later in the same poem, the line “It’s God, after all! He melted the clay and poured it”95Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 21. alludes to the Quranic account of human creation from clay. Sūrah al-Hijr (15:26) states, “Indeed, We created man from sounding clay moulded from black mud.”

In the poem “Andar hikāyat-i pul” (The story of the bridge), Taftī directly references Sūrah al-ʿAsr (103:2), which declares, “Surely humanity is in grave loss.” Taftī writes:

It’s a good thing I didn’t ruin things behind your back / And it is “humanity is in grave loss” deeply / By the water and beneath the willow and… on the bridge.96Taftī, Ragʹhāyam rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 63.

In the poem “ʿIshq va kūtāhi va marg” (Love and shortness and death), the poet refers to this verse with a Persian translation:

What if he was closer to me, next to me? / I escaped from his hands to his eyes / Sympathy is empty and dry / “We created humanity in grave loss” / I recognize him wherever I see him…”97Taftī, Iqlīm-i dāgh, 35.

More broadly, Quranic language and references frequently permeate Taftī’s poetry and can be found across numerous poems. For example, in “Khvudʹnivisht” (Autography), she writes, “I’m a female… / My mother says: You’re obstinate / My father says: You’re ruined in this world and the next [Sūrah Hajj (22:11)].”98Taftī, Iqlīm-i dāgh, 8. In “Khvāb-i abrīsham” (Silk sleep), Taftī writes, “All the pins went and didn’t hit the archive folder / They observed him and you and the city and the current state of the country and the fall/ and the human and ‘When the sun is put out’ [Sūrah al-Takwīr (81:1)] and the world disintegrates like an old cotton-ball and …”99Taftī, Iqlīm-i dāgh, 71.

The descent of Gabriel, the archangel mentioned three times in Quran, is referred to in the poem “Tūlānī rā duʿā kunīd” (Pray for the long): “Here, in honor of silence, die for one minute / Among the unwashed dishes / Sometimes, Gabriel descends upon me with fallen buttons…”100Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 38.

In addition to frequent Quranic allusions, Taftī does not hesitate to draw on hadiths (the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad and the Imams. For example, in the poem “Band” (Thread), she quotes the well-known saying of the Prophet Muhammad: “Seek knowledge even if it is in China.”101Muhammad bin Hassan bin ʿAlī (known as Hurr-i Āmilī), Vasāʾil al-Shīʿah (Qom: Āl-i Bayt, 1414/1992), 27: 27.

I won’t open my mouth / It reeks and travels far / Seek knowledge even if it is in China / Seek knowledge even from the embryo / Seek knowledge even my skirt is pleated.102Taftī, Iqlīm-i dāgh, 87.

Another dimension of religious intertextuality in Taftī’s poetry emerges in her invocation of historical-religious events. For example, in the poem “Sih-i nīmahʹshab” (Three in the morning), the poet alludes to the incident of Karbala and Imam Hossein’s cry for help, “Is there someone to help me?”:

How much can one prolong waiting? / And yet, you were perfect beyond words / The mother tongue wasn’t enough / It came, it didn’t come and still wasn’t enough / Though the mother tongue was perfect / It uttered “Is there someone to help me?” [in Arabic]103Taftī, Safar bih intihā-yi par, 84.

In the poem “Shām-i gharībān” (The supper of the homeless), the poet draws on the elements and atmosphere of Karbala to establish a connection with contemporary realities:

They came mourning from the wall, wanting a drop of milk / ʿAlī Asghar was thirsty / He came along and stuck to my face and seemed homeless / I had become more chemical.”104Taftī, Ragʹhāyam rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 75.

Here, the reference to ʿAlī Asghar, a six-month-old infant martyred in the Karbala event, creates a powerful emotional bridge between sacred history and modern suffering, blurring temporal boundaries and evoking a sense of shared vulnerability.

Beyond religious references, Taftī also draws on intertextuality through the use of recognizable expressions and statements from literary texts. A notable example appears in the poem “Tu ān yikī pūlakī” (You’re the other sequin), in which she writes:

… And when my laughters burst out of the multiplication table / a purple scream and boxes of colored pencils / What short eyes, alas…105Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 8.

The phrase “purple scream” is a well-known expression originally coined by Hūshang Īrānī in the second issue of the avant-garde literary magazine Khurūs-i Jangī (The fighting rooster) and later featured in his collection Az banafsh-i tund tā khākistarī (From strong purple to grey):

Hima Horai / Gil-u viguli… / Nibun… Nibun / The dark cave is running / Hands cupping ears and eyelids squeezed shut and bent over / letting out / an uninterrupted purple scream.106Hūshang Īrānī, Az banafsh-i tund tā khākistarī [From strong purple to grey] (2nd repr. ed., Tehran: Nukhustīn, 1387/2008), 19.

In the following lines from the poem “5,” Taftī refers to the concepts of “shadow” and “the dark half”:

From my heart which is exactly the size of a closed fist / They ask, what do you expect? / I’m saying this only for the dark half / That folds over and over, just for me / The shadow drags itself beneath my skin, what can I do?107Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 42.

These lines evoke Sādiq Hidāyat’s Būf-i kūr (The blind owl), where he writes:

I write only for my own shadow, cast upon the wall before the light. I should introduce myself to it… I can only speak well to my own shadow. It is he who makes me speak. Only he can know me. He knows, without a doubt… I wish to pour the essence, no, the bitter wine of my life, drop by drop into my shadow’s dry mouth and tell him: this is my life!108Sādiq Hidāyat, Būf-i kūr (Isfahan: Sādiq Hidāyat, 1383/2004), 19.

As previously discussed, the children’s rhyme “Khassah shudīm” (We’re tired) exhibits intertextual connections to folklore and literature, particularly through its references to various games:

Once upon a time… / For all the children / The games were like a fountain in the air / The one whose right eyelids twitched / became Galilei / The one who cut his shoelace / became a martyr / We are open, we are close / We are open, we are close / We are the knife, we are the handle / We are the plum, we are kernel / When it’s absent, we are tired / There’s dirt on our shoes /… Hey, will you play hide-and-seek with the one who isn’t there? / I say hide-and-seek / He says Atal Matal / He turns this way and that way / He sweeps the sky / Āchīn-o vāchīn / Pull up one of your legs.109Taftī, Sāyah lā-yi pūst, 48–49.

In her poem “Kārnāvāl” (Carnival), Taftī mentions not only the names of prominent postmodernist thinkers but also incorporates the title of Michel Foucault’s seminal book, Madness and Civilization (translated into Persian by the title Tārīkh-i junūn, which translates to History of Madness). The poem reads:

Last night, some of you came into my dream / The analysis of my departure turned green and full / Until you measured history against my madness… / I named my son Barthes / my husband Foucault / … Am I not? What am I? De Barthes Derrida Foucault Lyotard / Shake me / And I become not waste, but recyclable and reusable / when I sit atop of Tehran with the poetry’s Nīmā.110Taftī, Ragʹhāyam rū-yi bulūzam mīʹguzarand, 28.

In the poem “Dihkadah-ʾi Mawʿūd” (Promised village), Taftī mentions Kurt Vonnegut’s renowned novel, Slaughterhouse-Five. Vonnegut, an American writer, was a prisoner of war in Dresden, Germany, during World War II. He was held in the basement of a slaughterhouse during the Allied bombing raids and later chronicled his experiences in the novel. Taftī writes:

I dreamed I was older last night / Maybe because of Slaughterhouse 5 / because of all the lights that I don’t see…111Taftī, Iqlīm-i dāgh, 16–17.

The phrase “all the lights that I don’t see” echoes the title of Anthony Doerr’s novel All the Light We Cannot See (2014), which won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize. The novel also touches upon the bombing of Dresden, telling the story of a blind French girl and a German boy navigating the ruins of World War II.

Taftī alludes to Dresden in yet another poem, “Muhkam bāsh” (Be strong). Dresden, a German city, endured four bombing raids in the final months of World War II, resulting in the release of over 39,000 tons of explosives and incendiary bombs. The intense from these bombings cause many victims to be burned beyond recognition, with their bodies reduced to ashes while their clothing remained intact. In her poem, Taftī writes:

Be strong like the back of Mount Qāf in a black hole in space / Like the goddess of virtue over the ruins of Dresden / Be strong! / Because I love you / Like dāl in the relief that follows hardship (shiddat)…112Taftī, Iqlīm-i dāgh, 30.

Conclusion

In conclusion, polyphony emerges as a defining and generative feature of Rawyā Taftī’s poetic practice, intricately tied to the broader postmodern turn in Iranian literature. Through the lenses of dialogism and intertextuality, Taftī constructs poems that resist closure, embrace multiplicity, and disrupt the authority of a singular poetic voice. Her strategic use of punctuation, fragmented narrative, overlapping speakers, and visual textuality allows distinct voices—human, non-human, textual, and cultural—to coexist dynamically within the same poetic field. At the same time, her intertextual engagement with religious texts, classical and modern literature, and popular culture further amplifies the dialogic structure of her work, layering registers and reactivating silenced or marginalized discourses. In navigating between inherited traditions and contemporary linguistic experimentation, Taftī offers a poetics of radical openness, one that redefines the function of poetry in an era marked by aesthetic innovation, social transformation, and intellectual pluralism. Her work not only exemplifies the postmodern ethos of the 1370s/1990s but also pushes its boundaries, positioning her as a central figure in the evolution of modern Persian poetry.