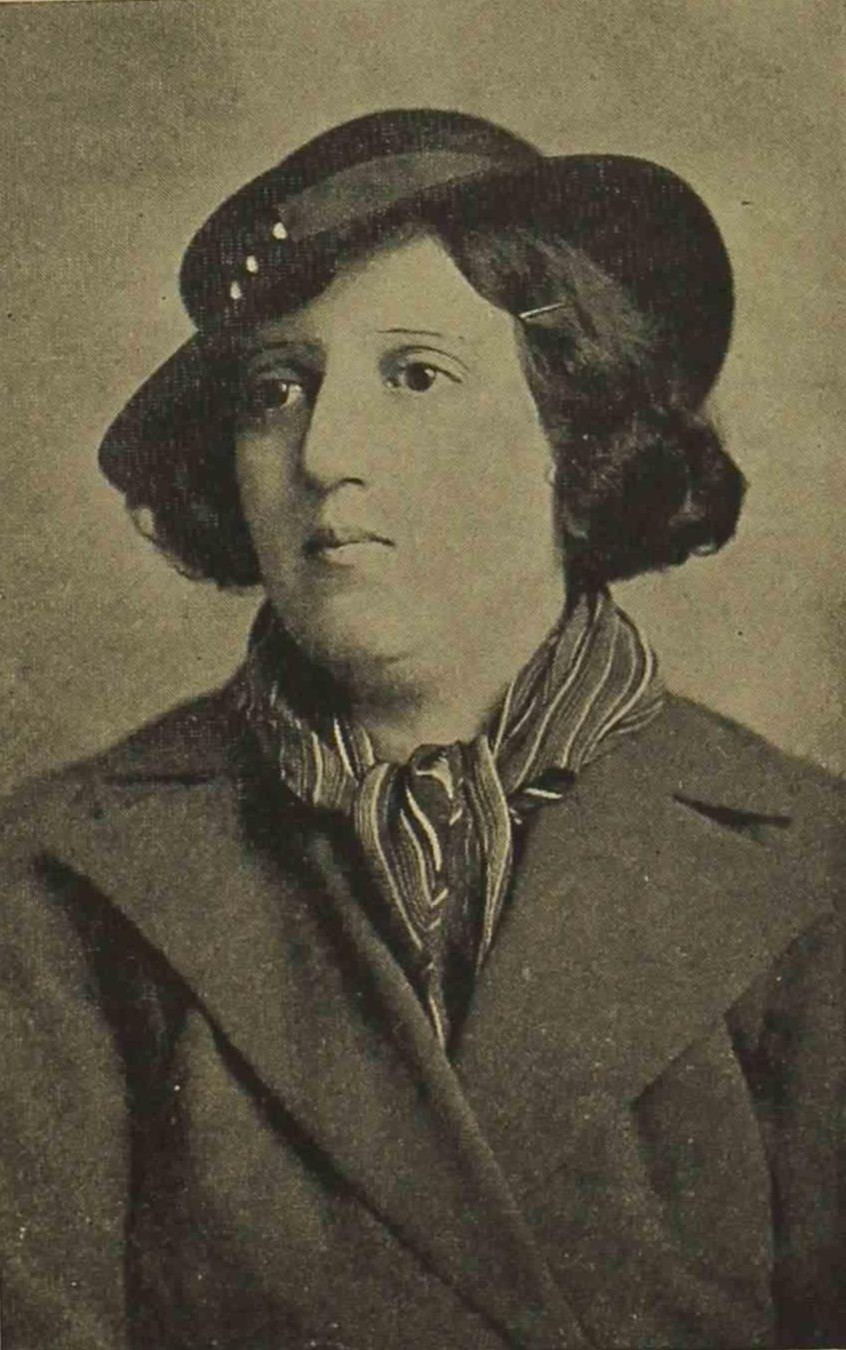

Parvīn Iʿtisāmī and Women’s Rights?

Introduction

In the realm of feminist Persian poetry, certain names are frequently encountered, including Tāhirah Qurrat al-ʿAyn (AH 1230–1268/1817–1852), Zandukht Shīrāzī (1288–1331/1909–1953), Sīmīn Bihbahānī (1306–1393/1927–2014), Furūgh Farrukh′zād (1313–1345/1934–1967), and, more recently, Zhālah ʿĀlamtāj Qāʾim Maqāmī (1262–1326/1883–1947). Surprisingly, the poetic contributions of Parvīn Iʿtisāmī (1285–1320/1907–1941) remain conspicuously excluded from such discussions. Scholarly attention has predominantly centered on the social dimensions of Parvīn’s poetry, encompassing her endeavors to portray and critique societal disparities. Nevertheless, a critical and foundational theme pervasive throughout her poetic corpus revolves around the concept of “inequality” in its entirety, encompassing the profound gender disparities between men and women. Regrettably, this essential aspect of her poetry has remained comparatively underexplored within academic discourse to date.1Among the few works on this topic are Zhinia Noorian, Parvin Etesami in the Literary and Religious Context of Twentieth-Century Iran: A Female Poet’s Challenge to Patriarchy (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2023); Farzaneh Milani, “Revealing and Concealing: Parvin E‘tessami,” in Veils and Words: The Emerging Voices of Iranian Women Writers (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1992), 100–26; and Behnam M. Fomeshi, “‘The Female Rumi’ and Feminine Mysticism: ‘God’s Weaver’ by Parvin Iʿtisami,” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 50 (2): 340–50. This article attempts to illuminate this lesser-known aspect of her work, aiming to present a distinct portrayal of a significant poet in the literary context of modern Iran. To achieve this objective, I begin by examining three critical factors that inform her poetry and subsequently delve into a selection of her poems that explicitly or implicitly address feminist themes.2The term “féminisme” was initially introduced by the French philosopher Charles Fourier in 1837. By the late nineteenth century, it had come to represent the idea of “equal rights for women.” Despite the development of more recent waves of feminism, both the term and the concept have long-standing histories. Thus, describing Parvīn’s efforts for women’s rights as “feminist” is not anachronistic.

The Formation of Parvīn’s Poetry

The formation of Parvīn Iʿtisāmī’s poetry can be attributed to a combination of her personal experiences, family background, education, societal developments, and feminist perspectives. These interconnected factors molded her poetic identity, making her a significant voice in Persian literature, especially when it comes to advocating for women’s rights and challenging the prevailing norms of her time. A significant factor contributing to Parvīn’s poetry, particularly concerning its representation of gender, was her father, Yūsif, whose works and translations familiarized her with the issue of women’s rights. He translated major literary works from French, Turkish, and Arabic, and a significant portion of his works published in the Bahār periodical concerned women’s rights.3The journal Yūsif established and where he published his translations and writings was titled Bahār: Majmūʿah-ʾiʿilmī, adabī, falsafī, sīyāsī, ijtimāʿī, akhlāqī (Spring: A scientific, literary, philosophical, political, social and moral collection). It was published in two volumes, one from Farvardīn 1289/April 1910 to Ābān 1290/November 1911 and the other from Farvardīn 1300/April 1921 to Āzar 1301/December 1922. For more on him and his journal refer to Behnam M. Fomeshi, “A Persian Translation of Whitman,” in The Persian Whitman: Beyond a Literary Reception (Leiden: Leiden University Press), 61–88. For instance, the inaugural issue of the journal included a piece entitled “ʿAqīdah-ʾi Zhūl Sīmūn: Islāh-i haqīqī” (Jules Simon’s idea: The true reform), which ended with the following sentence, “The hope of reaching the caravan of contemporary civilization is contingent upon improving the conditions of women and their education.”4Yūsif Iʿtisāmī, “ʿAqīdah-ʾi Zhūl Sīmūn: Islāh-i haqīqī,” Bahār 1, no. 1 (1289/1910): 14. The second issue included a piece entitled “Ikhtirāʿāt-i nisvān” (Inventions by women). The materials concerning women’s rights published in the journal were so significant that when it was reprinted in the early 1320s/1940s, a chapter, entitled “ʿĀlam-i nisvān” (The world of women), was devoted to this topic.5Both volumes were reprinted by Yūsif’s son, Abū al-Fath Iʿtisāmī, in Tehran at the printing office of the Majlis; the first volume in Murdād 1321/1942 and the other in Isfand 1321/1943. Abū al-Fath divided the content of the first volume into seventeen categories and that of the second volume into sixteen, with only minor modifications compared to the first volume. Both volumes contained a chapter titled “ʿĀlam-i nisvān” (The world of women), devoted to this topic. His activities in the field precede such pieces in Bahār. In 1279/1900, several years prior to the Persian Constitutional Revolution (1284–1290/1905–1911), he published Tarbīyat-i nisvān (The education of women), which was his translation of Qāsim Amīn’s Tahrīr al-marʿa (The liberation of women, 1899) on women’s rights and freedom. Yūsif Iʿtisāmī was among the first to publish on the issue in Persian, and this book was the earliest book solely dedicated to women’s issues written or translated in Iran.6Behnam M. Fomeshi, “‘Till the Gossamer Thread You Fling Catch Somewhere’: Parvin E‘tesami’s Creative Reception of Walt Whitman,” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 35, no. 3/4 (2018a): 267–75, online at https://doi.org/10.13008/0737-0679.2290. Parvīn’s exposure to such works informed her writings. Her ideas, as expressed in her works, show close affinity with those of Tarbīyat-i nisvān.7Siyid Muhammad Rizā Ibn al-Rasūl and Muhsin Muhammadī Fishārakī, “Parvīn Iʿtisāmī va asar′pazīrī az andishah′hā-yi Qāsim Amīn munādī-i āzādī-i zan dar Misr” [Iʿtisāmī and the impact of Qāsim Amīn, the forerunner of women’s liberation in Egypt], Adabiyāt-i tatbīqī 5 (1390/2011): 1–24. While her father contributed to advancing women’s rights through translation, Parvīn did so through writing poetry, some of which are examined more closely in the following sections.

Throughout her brief life, Parvīn bore witness to several momentous events that significantly shaped the history of modern Iran. These events encompassed the Constitutional Revolution, the prorogation and bombardment of the Majlis (the Parliament), the First World War, the 1300/1921 coup, and Reza Shah’s modernization and autocratic rule. It was amidst this tumultuous backdrop that she developed an acute sensitivity towards the intricate sociopolitical landscape of her homeland.8Behnam M. Fomeshi, “Parvin Eʿtesami,” in Iranian/Persian Writing and Culture, edited by Laetitia Nanquette, vol. 7.1.1. of The Literary Encyclopedia (2018b), online at https://www.litencyc.com/php/speople.php?rec=true&UID=14067. Another noteworthy development of that period was the shifting attitude towards women and their societal status in Iran. Parvīn experienced these developments first hand, not solely through her reading habits, which included her father’s translations, but also through her active participation in his father’s gatherings with friends. Even during her childhood, she would attentively sit beside him for extended periods, eagerly absorbing the conversations that took place during these gatherings.9Maryam Musharraf, Parvīn Iʿtisāmī: Pāyah′guzār-i adabiyāt-i niʾu′kilāsīk-i Īrān [Parvīn Iʿtisāmī: The founder of Iranian neo-classic literature] (Tehran: Sukhan, 1393/2012), 120. Yūsif’s literary writings and translations coupled with the prevailing social conditions of the country suggest that women’s rights may have been one of the topics addressed in those gatherings. By actively participating in these meetings, Parvīn not only acquainted herself with the intricacies of women’s rights but also recognized its intersections with various other pressing social, political, and cultural matters that the nation grappled with. In her poem “Du mahzar” (Two courts), a poignant dialogue between a wife and her judge husband, Parvīn eloquently touches upon several pertinent themes. She keenly addresses the corruption prevalent within the judicial system while simultaneously emphasizing the significance of the overlooked realm of housework. The poem portrays the role of a housewife as surpassing that of a judge in its importance and impact. This compelling poetic composition attests to Parvīn’s acute awareness of the intricate interplay between women’s rights and the broader spectrum of social and political issues that prevailed within the nation.10Fomeshi, “‘The Female Rumi and Feminine Mysticism,’” 101.

Another pivotal element influencing Parvīn’s cognizance of women’s rights was her association with Iran Bethel, the American school for girls in Tehran, founded by American missionaries in 1253/1874. Her enrollment in 1301/1922 introduced her to the educational institution, and following her graduation, offered her a teaching role. This academic environment not only exposed her to Western literature and thought but also served as a conduit for fostering her understanding of women’s rights and their pursuit in a broader global context.11Fomeshi, The Persian Whitman, 102. Iran Bethel played a significant role in promoting awareness and activism for women’s rights through the publication of the journal ʿĀlam-i nisvān (The world of women, 1300–1312/1921–1933) for over a decade.12This journal is not related to the chapter of the same title in the reprint of the journal Bahār, previously discussed. This pioneering journal was among the first in Iran solely dedicated to women’s issues, encompassing a diverse range of topics. Notably, it featured articles on the advancements of women in various countries, both Western and Islamic, while actively advocating for positive transformations in the social status of Iranian women. Serving as the most enduring publication of its time in this domain, the journal fearlessly broached subjects concerning women’s participation in political activities, and courageously critiqued prevalent practices like early marriage and veiling.13Maryam Husaynī, “Shiʿr-i fimīnīstī-i nawʹyāftahʾī az Parvīn Iʿtisāmī” [A newly-found feminist poetry by Parvīn Iʿtisāmī], Zan dar farhang va hunar 2, no. 1 (1389/2010): 5–22. Through these endeavors, the journal aimed to inspire positive change and foster progress for women in Iranian society. The contributors to ʿĀlam-i nisvān included the graduates of Iran Bethel, and the journal’s content reflected the topics studied and explored in the school’s curriculum and by its members. With an extensive distribution network of over forty sales representatives throughout the country, the journal played a pivotal role in making knowledge accessible to Persian readers, especially among the students of the school, including Parvīn. She delivered a thought-provoking talk titled “Zan va tārīkh” (Women and history) and recited her poem “Nahāl-i ārizū” (Sapling of ambition) during her graduation ceremony. The former shed light on the divergent conditions of women in the East and the West, while the latter eloquently emphasized the paramount importance of education for women. Both her talk and poem found their way into the pages of the journal, further amplifying their impact and dissemination of these insightful perspectives. The poem was highly controversial due to its bold stance in defense of women’s rights and its direct challenge to the prevailing patriarchal norms. In fact, Parvīn’s father opted for not including this poem in the initial edition of her divan to avoid potential backlash from both religious authorities and the public.14Jalāl Matīnī, “Nāmah′hā-yi Parvīn Iʿtisāmī va chand nuktah darbārah-ʾi dīvān-i shiʿr va zindigānī-i viy” [Parvīn Iʿtisāmī’s letters and a few points concerning her collection of poetry and life], Īrān′shināsī 13, no. 1 (1380/2001): 1–45. According to Brookshaw, without such discouragement, Parvīn could have crafted more poems of this kind.15Dominic Parviz Brookshaw, “Chapter Five: Women Poets,” in Literature of the Early Twentieth Century: from the Constitutional Period to Reza Shah, ed. Ali Asghar Seyed-Gohrab. (London: I.B. Tauris, 2015), 240–310. However, her existing poems on the subject are still of considerable significance.

In her insightful monograph on Parvīn, Noorian astutely points out that the significance of Parvīn’s “transgression of the long-established gender boundaries has escaped analysis.”16Noorian, Parvin Etesami in the Literary and Religious Context of Twentieth-Century Iran. While some critics such as Leonardo Alishan have criticized Parvīn for passively endorsing patriarchy,17Leonardo Alishan, “Parvin Eʿtesami, the Magna Mater, and the Culture of the Patriarchs,” in Once a Dewdrop: Essays on the Poetry of Parvin Eʿtesami, edited by Heshmat Moayyad (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1994), 20–46. a careful analysis of her poetry, including the aforementioned poem, reveals a different narrative. Exemplifying her willingness to confront and defy patriarchy, such compositions reject the readings that suggest she blindly supported patriarchal structures. As the following section demonstrates, poems such as “Nahāl-i ārizū” and others discussed below highlight her courage and determination to challenge the prevailing social norms and to advocate for women’s rights.

Parvīn’s Poetic Advocacy: Championing Women’s Rights

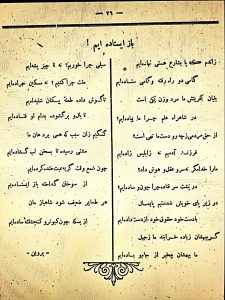

The poem “Bāz īstādahʹīm” (We are still standing) was published in ʿĀlam-i nisvān.18Parvīn Iʿtisāmī, “Bāz īstādahʹīm,” ʿĀlam-i nisvān 1, no. 6 (1300/1921): 26. The poem eloquently refers to men’s injustices against women while simultaneously attributing agency to women and holding them partially responsible for their adverse circumstances. Notably, all the first-person plural pronouns, with the exception of one in line three, pertain to women. This strategic rhetorical device serves the purpose of fostering a collective consciousness among women. By employing this literary technique, the poem enhances the collective sense of community between women in Iranian society, which she considered a prerequisite for a large-scale, i.e., nation-wide, change.

We Are Still Standing

From the moment we [women] have entered the thoroughfare of existence,

We have been stopping every two steps.

We -men and women- share the essence of creation,

Why are we afoot on the path of knowledge?

Why are our hands empty of the most basic rights?

We are children of Adam, not born of Satan.

Did God not grant us with brains, reason, and intelligence?

Why do we fall behind like pillows?

We have been downtrodden under our own feet

We have lost our rights with our own hands.

While the drunkards are lost to wine, we are to ignorance

We are the lost with no cup and no wine.

Why get slapped? We are no worthless mosquitoes19The line reads: سیلي چرا خوریم؟ نه ناچیز پشه ایم

Why beg? We are no helpless insects.

Anytime we listen, we hear the sarcasm of arrows

Any time we open our wings, we are trapped.

We are voiceless as we were punched in the mouth

Any time we opened our mouth to talk.

Like a candle we have laughed when we should have cried

We have stopped melting while burning.

We fall prey to any hawk-like feeble flock

We are as naïve as pigeons and sparrows are.20The translation is done by the author. This is the first ever English translation of this poem.

Figure 1- Parvīn’s poem in ʿĀlam-i nisvān 1, no. 6 (1300/1921): 26.

Husaynī has demonstrated that the poem, which remains absent from all editions of Parvīn’s divan, indeed belongs to her.21Husaynī, “Shiʿr-i fimīnīstī-i nawʹyāftahʾī az Parvīn Iʿtisāmī,” 5–22. Notably, the theme of women’s rights, ubiquitous in her later poems, is initially introduced in this poem. Such a bold undertaking on the part of the poet is noteworthy for two reasons. First, Parvīn was merely fifteen years old when she composed this poem, which adds to the remarkable nature of her literary feat. Second, the reference to human rights in the Persian poetry of the early 1300s/1920s was unprecedented, further exemplifying the poem’s significance as a groundbreaking expression of progressive ideals within that era.

Before the publication of “Bāz īstādahʹīm”, two other poems composed by Parvīn had already been featured in ʿĀlam-i nisvān . These poems were titled “ay murghak” (O little bird) and “Nawrūz va bahār” (Nowruz and Spring).22Respectively, ʿĀlam-i nisvān 1, no. 2 (1300/1921): 25 and ʿĀlam-i nisvān 1, no. 4 (1300/1921): 26–29. Notably, the author’s name for these two poems was “P.N.,” the first and last letters of Parvīn’s first name. However, it is significant that it was with the publication of “Bāz īstādahʹīm” that the poet’s name was first written as “Parvīn” in the journal. Moreover, this poem marks the inception of Parvīn’s poetic engagement with women’s rights, signifying her first notable contribution to this vital theme within her poetic repertoire. As such, “Bāz īstādahʹīm” remains a pivotal poem that firmly establishes the identity of Parvīn as a poet who engages with women’s rights. This significant literary work marks a turning point in her poetic journey, as a poet who fearlessly delves into the realms of social justice and gender equality, leaving a lasting impact on the discourse of women’s rights in Persian literature.

The poem “Nahāl-i ārizū”, which appeared in ʿĀlam-i nisvān, serves as a compelling call to action, urging women to pursue knowledge and artistic endeavors as prerequisites for claiming their rights.23 ʿĀlam-i nisvān 4, no. 5 (1304/1925): 16. In this poem, a noteworthy departure from traditional gender norms occurs in a comparison between men and women, asserting that knowledge, rather than gender, marks one’s superiority. Additionally, the poem attributes the subordinate position of women to their lack of education and awareness, thereby emphasizing the significance of knowledge in shaping their empowerment. According to Brookshaw, this poem encapsulates some of the poet’s “most outspoken comments” on the position of women in Iranian society.24Brookshaw, “Chapter Five: Women Poets,” 307. Published during the early 1920s, a time when traditional mindsets prevailed in the country, the poem’s subject matter was profoundly revolutionary. It courageously defended women’s rights and challenged the prevailing status quo against a conservative backdrop. This bold expression of feminist ideals within the poem, which Noorian calls “a manifesto of women’s rights,” proved its publication a significant event and identified Parvīn as an early feminist poet of modern Iran.25Noorian, Parvin Etesami in the Literary and Religious Context of Twentieth-Century Iran, 140. The poem’s controversial nature is further underscored by its absence from the initial edition of Parvīn’s divan in 1314/1935, a full decade after its first appearance in ʿĀlam-i nisvān. This fact not only highlights Parvīn’s status as a pioneering feminist voice but also accentuates the journal’s position as a platform advocating women’s rights. Furthermore, it highlights the progressive stance of the American School for girls in Tehran, which nurtured her intellectual growth and provided a supportive environment for her exploration of feminist themes.

The poem “Ganj-i ʿiffat” (Treasure of chastity)26Also known as “Zan dar Īrān” (Women in Iran). further accentuates the significance of knowledge and sheds light on men’s deliberate attempts to withhold it from women. This poem, composed in response to Reza Shah’s unveiling decree, is particularly relevant to the socio-political context of the time. On Day 17, 1314/January 8, 1936, Reza Shah issued a decree that prohibited the use of all veils, including the headscarf and the chador, mandating the unveiling of women. While the unveiling decree was strongly opposed by the traditional and religious sectors of the society, the poem emphasizes the decree as a crucial milestone in conferring Iranian citizenship status on women. While the author acknowledges the controversy surrounding Reza Shah’s unveiling decree, this article concentrates on the poet’s appreciation of the decree, as revealed through a close reading of her poem contexualized within her poetic career. The very first line of the poem brings attention to the prevailing reality that prior to this decree, women in Iran were not recognized as Iranian citizens: “Prior to this, a woman in Iran was not an Iranian (citizen).” The poem echoes the sentiment expressed in Reza Shah’s speech at the graduation ceremony of Tehran Teacher’s College on Day 17, 1314/ January 8, 1936, wherein he acknowledged that, until that point, half of the nation’s population had been disregarded and women had been unjustly deprived of their rights.27Hamīd ʿAlavī, “Zanān-i Īrān va hijāb, kishmakish-i hashtād sālah” (Iranian women and the hijab, an eighty-year struggle), BBC Persian, Day 16, 1394/January 6, 2016. The act of unveiling aimed to bestow upon Iranian women a new identity, one anchored in knowledge, chastity, and simplicity, rather than being solely associated with the traditional “frowsy/tattered” chador. The title of the poem, “Ganj-i ʿiffat” , reiterated in the verse, “the eye and the heart need veiling, but the tattered chador is not the foundation of Muslimhood,” challenged the long-established correlation between veiling/chador and chastity, and resonated with a key segment of Reza Shah’s speech. In his speech, Reza Shah addressed potential opposition to the unveiling initiative, where concerns about chastity and decency were raised. However, he countered that by asserting, “Decency and chastity have nothing to do with the chador. Are the millions of unveiled women in foreign countries indecent?”28ʿAlavī, “Zanān-i Īrān va hijāb” Challenging the traditional perceptions surrounding veiling and virtue, the poem “Ganj-i ʿiffat” aligns with the discourse of societal transformation during that period and highlights the poet’s perceptions of women’s identity in relation to the unveiling decree.

Despite Parvīn’s sensitivity towards the sociopolitical state of the nation, her poems do not contain explicit political commentary, perhaps partly due to her reserved personality. This characteristic suggests her poetic focus on broader themes rather than specific political events. Nevertheless, she wrote a poem on the occasion of the unveiling decree. Secondly, while her poetry consistently critiques people in power, including kings, “Ganj-i ʿiffat” stands out for its praise for Reza Shah’s unveiling initiative. It is therefore reasonable to argue that the composition of a poem dedicated to this specific occasion and in celebration of Reza Shah’s mandate signifies Parvīn’s appreciation for what was considered the profound significance of this social development for Iranian women. The poem is Parvīn’s depiction of the transformative impact of the unveiling decree on women’s rights and their societal status, even amidst her general inclination to avoid overtly political subjects. By extolling Reza Shah’s initiative in poetic form, Parvīn acknowledges the significance of this social change and its influence on the trajectory of women’s “empowerment” in early-twentieth-century Iran.

The poem “Firishtah-ʾi uns” (Angel of affection) encapsulates key themes discussed earlier, stressing the significance of women’s education, knowledge, and art, while cautioning against arrogance and vanity fueled by external beauty. It also underscores gender equality and identifies knowledge as the sole criterion for superiority. Recognizing the crucial role of women in nurturing the future generation, the poem aptly refers to them as “the pillars of the house of existence” and argues “If Plato and Socrates are great / (it is because) their childhood care-givers (mothers) were great.” A humorous touch is evident in the verse: “Woman was an angel the moment she appeared / Look at the angel that Satan taunts.”29The translations is done by the author. Additionally, the second line challenges the patriarchal view that propagates the perfection of men and imperfection of women, often justified by excerpts from religious texts such as Nahj al-balāghah (The path to eloquence), attributed to ʿAlī, the first Shiʿa Imam. Parvīn’s poetic prowess beautifully encapsulates these essential aspects, reflecting her insightful observations and commitment to advocating for women’s empowerment and equality.

Apart from Parvīn’s poems that explicitly addressed women’s rights, other poems in her repertoire offer multiple semantic layers that lend themselves to feminist interpretations. A notable example is “Jūlā-yi khudā” (God’s weaver), belonging to the debate genre. This poem features a compelling exchange between a spider and a lazy person. Although the poem does not explicitly mention women, as Ahmad Karimi-Hakkak has also noted, the spider’s character embodies feminine attributes,30Ahmad Karimi-Hakkak, Recasting Persian Poetry: Scenarios of Poetic Modernity in Iran (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1995), 161–82. indicating an underlying resonance with women’s experiences. Through this poetic technique, Parvīn ingeniously weaves together a nuanced portrayal that encourages feminist readings, offering new insights into the representation of women in her poetry. The portrayal of the spider in the poem God’s Weaver exhibits several attributes traditionally associated with femininity, as exemplified by the spider being referred to as a “weaver,” “placed behind the door,” engaged in “cooking,” and using a “spindle” as her tool.31The English translation of “Jūlā-yi khudā” cited in this chapter is from Karimi-Hakkak, “Appropriation: Parvin’s ‘God’s Weaver,’” in Recasting Persian Poetry, 161–82. The symbolism of the “spindle” as a feminine tool merits further examination, which I will explore shortly. Furthermore, the spider’s act of “hanging” a “pardah,” which is the Persian term for both “drape” and “hymen,” becomes significant as it signposts “veil” as well as “female virginity,” closely intertwined with physical female attributes.32Fomeshi, “‘The Female Rumi’ and Feminine Mysticism,” 10. Notably, the interaction between the spider and the lazy person unfolds with the latter stating, “none will see you behind this door / none will call you any kind of artist.” These lines accentuate the feminine aspect attributed to the spider, portraying her as a female poet, profoundly confined within the domestic sphere, and relegated to invisibility as an artist within the patriarchal system.33Fomeshi, “‘Till the Gossamer Thread You Fling Catch Somewhere’,” 108. The textual analysis of God’s Weaver reveals an intricate interplay of gender symbolism and societal constructs, illustrating the spider’s representation as a metaphor for a female poet bound by traditional gender roles and limited recognition within the patriarchal framework. The weaving of these subtle nuances and gendered signifiers in Parvīn’s poetry adds layers of complexity, offering a rich ground for feminist interpretations and highlighting her astute observations on gender dynamics within the broader socio-cultural context.

According to Karimi-Hakkak, God’s Weaver includes dialogues between “two emblematic entities opposed to one another in an important character trait.”34Karimi-Hakkak, Recasting Persian Poetry, 161–62. The debate in the poem can be interpreted as a confrontation between a woman and a patriarchal system, wherein the arguments put forth by the two parties are asymmetrical in their persuasiveness. The poem can be understood in four parts, with parts one, three, and four exalting the spider/woman, leaving the reader with an impression of inevitable triumph. In the first part, the spider is depicted as industrious, forward-looking, and skilled in her art of weaving intricate patterns flawlessly. The debate commences in part two, where the lazy person presents their argument, assuming an air of authority but failing to offer coherent and structured reasoning, contrasting the spider’s meticulous web.35Karimi-Hakkak, Recasting Persian Poetry, 175. Part three follows with the spider presenting her compelling and well-structured response, further strengthening her position. Part four concludes the debate, mirroring the spider’s previous argument and serving either as the summary of her defense or as the poet’s reflections on the narrative. The conclusion resembles the spider’s argument so closely that it seems “rhetorically indistinguishable from the spider’s response” in part three.36Karimi-Hakkak, Recasting Persian Poetry, 172. Throughout the poem, the spider, symbolizing the woman, emerges as the victor, skillfully dismantling the weak arguments of the lazy person, symbolizing the patriarchal system. This nuanced portrayal of a confrontation highlights the poet’s celebration of the spider/woman’s strength and resilience, ultimately asserting her triumph over the constraints imposed by the patriarchal society. The poem’s multilayered discourse showcases Parvīn’s astute insights into gender dynamics and her skill in crafting a compelling feminist narrative.

The spider/woman in God’s Weaver exhibits mystical characteristics, exemplified by her “piety and indifference toward worldly pleasures.”37Fomeshi, “‘Till the Gossamer Thread You Fling Catch Somewhere’,” 110. The title itself reinforces her connection to the divine, as she acknowledges being guided by God’s plan and considers him the master of her work. The poem uses the term “friend” as a reference to God in mystical literature.38Karimi-Hakkak, Recasting Persian Poetry, 176. Not only is the interweaving of Persian poetry and mysticism evident in the poem, but the spider’s feminine and mystical attributes harmoniously merge.39Fomeshi, “‘The Female Rumi’ and Feminine Mysticism,” 348–49. This fusion can be traced from the title throughout the poem, culminating in the final verse: “The spider, my friend, is God’s weaver / Her spindle turns, but noiselessly.” These mystical traits of the spider in the poem evoke the subject matters and style of Rūmī.40ʿAbd al-Husayn Zarrīnkūb, Bā kārvān-i hullah [Along with the silk caravan] (Tehran: ʿIlmī, 1398/1991). Although Parvīn is comparable to renowned mystical Persian poets, there is a significant difference in her approach. While those poets predominantly focus on “mardān-i khudā” (God’s men) in their poetry, Parvīn, identifying as “the female Rumi,”41Abū al-Fath Iʿtisāmī, “Nāmah-ʾi āqā-yi Abū al-Fath Iʿtisāmā,” in Dīvān-i Parvīn Iʿtisāmī, ed. Hishmat Muayyad (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1365/1986), 276. challenges this prevailing view in mystical literature by granting women an equal position, symbolized through the character of the spider. This appropriation liberates the latent energy of mystical Persian poetry from the constraints imposed by patriarchal voices dominating the poetic tradition.42Fomeshi, “‘The Female Rumi’ and Feminine Mysticism,” 346. Through her poetic expression, Parvīn emerges as a defiant figure, breaking away from conventional norms to advance the recognition and empowerment of women in mystical literature.

Parvīn Iʿtisāmī’s treatment of the term “spindle” offers insights into her commitment to celebrating women. As previously noted, the spindle holds a significant place as a feminine tool in Persian literature, with precedents found in the works of Firdawsī and Vahshī. Moreover, the “spindle,” associated with the purportedly “feeble sex,” has been disparagingly employed in Persian poetry to demean men.43Fomeshi, The Persian Whitman, 107. In her poems, particularly those directly or indirectly addressing women, Parvīn transforms the “spindle” into a symbol of feminine pride.44Fomeshi, “Dūk-i himmat dar dastān-i ʿankabūt-i dawʹragah: Pazīrish-i khallāq-i Parvīn Iʿtisāmī az shiʿr-i Vālt Vītman” [The spindle of endeavor in the hands of a mixed-breed spider: Parvīn Iʿtisāmī’s creative reception of Walt Whitman], Mutāliʿāt-i Biyn-i Rishtahʾī-i Adabiyāt, Hunar va ʿUlūm-i Insānī 1, no. 1 (1400/2021): 79–93. https://doi.org/10.22077/ISLAH.2021.4108.1025 In God’s Weaver (“Jūlā-yi Khudā”), she introduces “the spindle of endeavor,” while in “Ganj-i ʿiffat”, she refers to “the spindle of art.” Notably, in the poem “Firishtah-ʾi uns,” Parvīn mentions “the spindle of reason,” a significant depiction that not only elevates women and the feminine “spindle” but also reflects her conscious effort to challenge the presumed mutual exclusivity of affection and reason, portraying a more comprehensive image of women. Through her poetic exploration of the spindle, Parvīn reinforces the value and significance of women and their multifaceted attributes. Her deliberate use of this symbol in diverse contexts shows her dedication to empowering women and dismantling traditional stereotypes, while also embracing the intricate complexity of women’s identities. In redefining spindle as a powerful emblem of feminine pride, Parvīn’s poetry emerges as a progressive force in reshaping societal perceptions and fostering gender equality in the literary realm.

Conclusion

The poetry of Parvīn Iʿtisāmī is imbued with her tireless efforts to celebrate women and advocate for their rights, even though these expressions are often concealed within the conventional structures of her verses. A close examination of her works brings to light a profound dedication to feminist ideals and the empowerment of women, as evidenced in the present article. Parvīn’s poetic legacy stands as a testament to her unwavering commitment to advancing gender equality. Through this exploration of the understudied dimensions of her poetry, the present article seeks to grant Parvīn the recognition she deserves in discussions revolving around feminist Persian poetry. She merits a place among revered poets like Farrokhzad, Behbahani, and others who are more widely acclaimed. Parvīn’s evocative verses continue to inspire and resonate with readers, championing the rights and empowerment of women, and fostering the pursuit of a more just and equitable society.45The author extends heartfelt gratitude to Samaneh Farhadi for her valuable insights, Mehrdad Babadi for his intellectual support, and Stephanie Hogan for her meticulous reading of this work. Special thanks are also due to Women Poets Iranica, with particular appreciation for Sheida Dayani, Abolfazl Moshiri, and Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi.