Nayyirah Saʿīdī, a Poet in Search of Women’s Rights

Introduction

One significant outcome of Iran’s encounter with Western thought, beginning in the early 14th/20th century, was the emergence and growing participation of women in scientific, social, cultural, political and artistic fields. During the Qajar period and earlier, women’s roles were largely confined to domestic responsibilities and family life. However, with the rise of the Pahlavi dynasty, the spread of modernist ideologies, and the gradual retreat of traditional views, new opportunities began to open for women in education, society, the arts, and politics. Many women pursued higher education both in Iran and abroad, seeking to claim visible and influential roles in these field. In doing so, they actively resisted efforts by traditionalist forces to confine them to private sphere. Their aim was to introduce and embody new models of the modern Iranian woman within society.

Nayyirah1On some of her works, her first name was written as Nayyir. Saʿīdī was among these pioneering women who advanced the project of modernization and left behind influential and enduring contributions to her society. Through her literary output and social and political engagement, she raised awareness among women about their rights and helped cultivate an environment in which those rights could be recognized and defended against the pressures of misogynistic ideologies. At the same time, Nayyirah remained committed to certain familial and cultural traditions, demonstrating that women could achieve prominence in academic, social, artistic, and political spheres while also embracing nurturing and supportive roles in the family. She showed that these responsibilities, far from being in conflict, could be carried out with purpose and success.

A Look at Nayyirah Saʿīdī’s Life

Nayyirah Saʿīdī was born in 1299/1920 into a culturally literate family. Her father, Sayyid Mūsā Muʿīr al-Mulk Mīrʹfakhrāyī, a veteran intellectual, and her mother, the daughter of Abū-Turāb Nazm al-Dawlah Khājah-Nūrī, shared a deep love for poetry and literature, often composing verses for family events or work-related occasions and introducing her to Persian verse.2Nayyirah Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah [The role of the future] (Tehran: pub. by author, 1369/1990), 7. Her parents employed a nurse well-versed in Firdawsī’s Shāhʹnāmah and Hāfiz’s Divān, who constantly recited their poetry to her. As a result, Nayyirah’s poetic talent flourished early,3Ittilāʿāt-i bānuvān [Ladies’ news] 188 (Āzar 1339/December 1960): 5. and she began composing children’s poems at home and in school, encouraged by her mother.4Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 7. She also began learning French in early childhood. Her maternal ancestor, Nazm al-Dawlah, head of Tehran’s police (nazmiyah) under Nāsir al-Din Shāh Qajar, was fluent in French and urged his descendants to learn it, so Nayyirah grew up in a francophone household and absorbed the language naturally.5Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 4.

After spending her first six years immersed in a cultural and poetic environment, Nayyirah’s family enrolled her in the Jeanne d’Arc School, founded on the French educational model and instructed in French. Prominent women such as Farah Dībā Pahlavi also studied there. Over twelve years of primary and secondary education, she attained fluency in French and memorized many French poems.6Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 7. During this period, she became aware of Western thought and reformist movements and recognized the differing attitudes toward women in traditional Iranian verses modern Western societies. These years were formative for her intellectual development and poetic language.

Nayyirah’s first poem appeared in Īrān newspaper in 1314/1935, coinciding with Reza Shah Pahlavi’s unveiling decree (kashf-i hijāb). Nayyirah poetically endorsed the reform,7Sipīd va siyāh [White and Black], no. 24 (Day 1334/January 1955): 40. demonstrating her modernist leanings even in adolescence.8Ittilāʿāt-i bānuvān 188 (Āzar 7, 1339/November 28, 1960), 5.

In 1317/1938, Nayyirah entered the Teachers’ College, majoring in Persian language and literature, which reflects her deep-rooted interest in Persian letters. There, she engaged academically with Iranian poetry and literary criticism, exploring elements such as imagination, emotion, and rhetorical devices. Her comparative study of Persian and French literature further enriched her perspective. Although Nayyirah excelled in literary disciplines, she struggled in subjects like history. She recalled overcoming this by memorizing historical content in verse, which not only improved her grades but also showcased her poetic talent and mnemonic skills.9Ittilāʿāt-i bānuvān 188 (Āzar 7, 1339/November 28, 1960), 5. After graduating in 1320/1941, Nayyirah continued her studies in Persian and French language and literature.

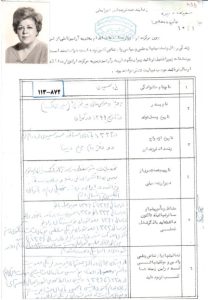

Nayyirah married the renowned historian and writer Nasr Allāh Falsafī in 1319/1940, but the marriage was short-lived. In 1322/1943, she married Muhammad Saʿīdī, a prominent politician and well-known author of the time (Figure 2).10Rawshanʹfikr [The enlightened], no. 162 (Shahrīvar 1335/September 1956): 20. Muhammad Saʿīdī, who later served three terms as a senator, recognized Nayyirah’s literary talent and her passion for social engagement. Rather than hindering her pursuits, he supported and encouraged her, creating the necessary conditions for her intellectual and professional growth.11Nayyirah Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 8. The couple had two daughters: Maryam, born in 1326/1947, and Mīnā, born in 1334/1955 (Figure 2).

Nayyirah’s involvement in cultural and literary circles and her interaction with prominent literary figures of the time, such as Bahār, Furūzānʹfar, Nafīsī, Rashīd Yāsimī, Nasr Allāh Falsafī, Taqīʹzādah, Sūratʹgar, Varzī, Rahī Muʿayyirī, Abū al-Qāsim Hālat, Amīrī Fīrūzʹkūhī, Mahmūd Farrukh, Muʿayyid Sābitī, Firaydūn Mushīrī, Sīmīn Bihbahānī, Nādir Nādirʹpūr, Muʿīnī and Navvāb Safā, played a crucial role in deepening her literary knowledge and refining her poetic sensibilities.12Nayyirah Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 8–9.

In 1324/1945, as her first social and cultural initiative, Nayyirah acquired a publishing license for the magazine Bānū under her brother’s name and ran it for three years until 1326/1947.13Ittilāʿāt-i bānuvān 188 (Āzar 7, 1339/November 28, 1960), 5. Bānū was the first specialized women’s magazine in Iran that refused to see women as confined to domestic spaces, instead advocating their engagement in various social, political, economic, and literary spheres. While publishing her own essays and poems, Nayyirah also created a platform for other women to write about the modern woman, thereby helping to nurture a generation of female writers.

In 1328/1949, Nayyirah traveled to Paris with her husband and stayed there for three years. During this time, she studied dramatic arts and psychology14Sipīd va siyāh 24 (Day 1334/January 1955): 41. at the University of Paris (Sorbonne)15Ittilāʿāt-i bānuvān 188 (Āzar 7, 1339/November 28, 1960), 5. Rawshanʹfikr 162 (Shahrīvar 1335/September 1956): 20. and perfected her knowledge of French there.16Ittilāʿāt-i bānuvān 188 (Āzar 7, 1339/November 28, 1960), 5. She also prepared her poems and essays for publication during this time.17Ittilāʿāt-i bānuvān 188 (Āzar 7, 1339/November 28, 1960), 5. Life in France had a profound impact on her thinking. What she had previously read and heard about modern societies and women’s roles she now experienced firsthand. This prompted her to reflect on how she could contribute to Iran’s intellectual and cultural renewal, particularly concerning women.

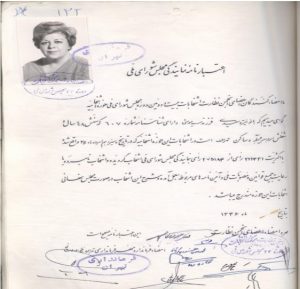

After her return, Nayyirah undertook several significant initiatives. Among them was co-founding the Royal Organization for Social Services (Sāzmān-i Shāhanshāhī-i Khadamāt-i Ijtimāʿī) alongside like-minded colleagues. She also became involved with numerous institutions, including the Iranian Red Lion and Sun Society (Jamʿīyyat-i Shīr va Khurshīd-i Surkh-i Īrān) and most major cultural organizations, notably the Supreme Council of Women (Shūrā-yi ʿĀlī-yi Jamʿiyyat-i Zanān). Her dedication led to her appointment as the spokesperson for the Supreme Council of Women, and from 1338/1959 to 1346/1967, she served as its head of public relations (Figure 2). Nayyirah’s other cultural responsibilities included membership in the Royal Cultural Council (Shūrā-yi Farhangī-i Saltanatī), the board of trustees of Pahlavi Library (Kitābʹkhānahʾi Pahlavī) (Figure 1) and the Surayyā Pahlavī Charity Society.18Rawshanʹfikr 126 (Day 1334/December 1955): 5. She also served as president of the Theater Enthusiasts Association, and a special inspector of the Royal Organization for Social Services (Figure 1).19Rawshanʹfikr 162 (Shahrīvar 1335/September 1956): 20. The goal behind these endeavors was to empower Iranian women to participate actively in cultural, artistic, and philanthropic institutions, and to demonstrate their vast potential, challenging gendered perceptions of social participation.

Another important initiative undertaken by Nayyirah was the establishment of a radio program titled Zan va zindigī (Woman and life), which she managed for two years, from 1333/1954 to 1335/1956 (Figure 2). Alongside Bānū magazine and other periodicals, this program allowed her to broadcast the voice and identity of the modern Iranian woman to a society in transition from tradition to modernity.

By 1335/1956, Nayyirah had attained a position of national prominence, representing Iran at the International Conference on Women’s Rights held in the Soviet Union. She attended the congress alongside Safīyah Fīrūz, the delegate from the Iranian Women’s Council (Shūrā-yi Zanān-i Īrān), Mihrī Āhī, representing the Society for the Support of Working Children and Women, and Mihrʹangīz Dawlatʹshāhī, the representative of the New Path Society (Jamʿiyyat-i Rāh-i Naw).20Rawshanʹfikr 162 (Shahrīvar 1335/September 1956): 21. The 15-day congress gathered delegates from all member states of the United Nations. At that event, Nayyirah became acquainted with the status and rights of women in various countries and gave a detailed presentation on the condition of Iranian women and their prospects.21Ittilāʿāt-i bānuvān 188 (Āzar 7, 1339/November 28, 1960), 5. Her subsequent travels to European countries such as the United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, Belgium, and Switzerland further enriched her perspective, allowing her to observe firsthand the lives of European women. These experiences enabled her to formulate her views on the roles and status of Iranian women with greater realism and to refine her reformist initiatives accordingly.22Rawshanʹfikr 162 (Shahrīvar 1335/September 1956): 20.

Beginning in 1334/1955, Nayyirah chose to reduce her public and social engagements to devote more time to raising and educating her first daughter, and later her second. Nevertheless, she remained committed to her literary and scholarly pursuits, including in translating French texts into Persian.23Sipīd va Siyāh 24 (Day 1334/January 1955): 40–41. Ittilāʿāt-i Bānuvān 188 (Āzar 07, 1339/November 28, 1960), 5.

In 1341/1962, Nayyirah became a member of the Radion Writers’ Council (Shūrā-yi Nivīsandigān-i Rādiyū) (Figure 2) and soon afterward assumed the presidency of the Society of Women Poets (Anjuman-i Bānuvān-i Shāʿir) (Figure 2). Her principal objective in radio programming was to raise Iranian women’s awareness of their social and political rights. Within the Society of Women Poets, her aim was to foster a literary network among Iranian women poets and to promote collaboration and mutual support within that network.

Figure 1: Credential as Representative of National Consultative Assembly (Majlis-i Shūrā-yi Millī). The document states that the members of the Supervisory Board for the elections of the 22nd National Consultative Assembly confirm that Nayyirah Saʿīdī, 48 years old and editor-in-chief of a magazine, received 222,431 votes out of a total number of 275,184 votes cast in the election. Dated 1346/1967

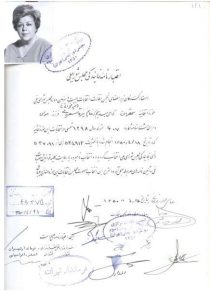

One of the achievements of Iran’s White Revolution (Inqilāb-i sifīd) in 1341/1962 was the enhancement of women’s social and political status. By 1343/1964, women were granted the right to participate in the elections as candidates for the National Consultative Assembly. Riding this wave of change, Nayyirah was appointed to the Royal Cultural Council by decree of Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavī in 1343/1964. From that year onward, she steadily elevated her political and social standing. In 1346/1967, she launched her political career by running for a parliamentary seat representing Tehran. Thanks to her dynamic public campaigning, especially among female voters, and her husband’s support, she secured 222431 votes out of 275,184, earning a seat in the 22nd National Consultative Assembly (Figure 1). This was only the second parliamentary term to include women. She replicated her success in the 23rd National Consultative Assembly, winning 524,913 votes out of 537,091 and becoming the representative of the nation’s capital once again (Figure 3).

Figure 2: A form submitted to the Ministry of Intelligence archives, completed by Nayyirah Saʿīdī, in which she provides information about her personal life, education, professional positions and assignments, as well as her social, academic, and literary activities.

During her tenure in parliament, Nayyirah continued championing women’s rights and social justice. Notably, in one speech she criticized the insufficient pensions of retired public servants, a speech that was highlighted by Habīb Yaghmāyī (d. 1363/1982), himself a former education retiree, who published it with an introduction in Yaghmā magazine.24Nayyirah Saʿīdī, “Bāznishastigān” [The retirees], Yaghmā 7, no. 301 (Mihr 1352/October 1973): 437–39.

Figure 3: Credential as Representative to the National Consultative Assembly (Majlis-i Shūrā-yi Millī). The document states that the members of the Supervisory Board for the elections of the 23rd National Consultative Assembly testify that Nayyirah Saʿīdī, born in 1298/1919, received 524,913 votes out of a total number of 537,091 votes cast in the election.

Dated Shahrīvar 26, 1350/September 17, 1971

After the 1357/1979 Islamic Revolution, Nayyirah withdrew from public life, focusing instead on poetry and supporting her daughters. Many of her later poems reflect the hardships of this period.25Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 117.

Finally, in 1370/1991, while visiting her children in France, Nayyirah Saʿīdī passed away in Paris on Murdād 21, 1370/August 12, 1991, and was laid to rest at Père Lachaise Cemetery, away from her homeland.

The Status of Women in Nayyirah Saʿīdī’s Political and Social Life

As previously noted, one of the most important missions Nayyirah Saʿīdī defined her social and political life was the advocacy of women and their rights in Iran. In her view, while men and women are not equal in terms of physical capacities and she believed that men should work more due to their greater physical strength, she firmly supported the equal rights of men and women. She was critical of the Iranian legal system of the 1320s/1950s, which she believed infantilized women by grouping them with the mentally ill and legally incapacitated. She also condemned the inheritance laws that gave greater custodial rights to a child’s paternal grandfather, or even uncle, that to the child’s own mother upon the father’s death. Nayyirah further objected to property and divorce laws that allowed a man to accumulate wealth with his wife’s help and yet divorce her unilaterally without providing her with any share of the jointly accrued assets. She advocated for the Western model of joint property rights between spouses.26Rawshanʹfikr 126 (Day 1334/December 1955): 5–6. She cited the 1336/1957 protest of Mrs. JārʹAllāhī who staged a sit-in in a mosque in protest of injustices by her former husband as further evidence of the need to reform custody laws. Nayyirah insisted that custody after divorce should be awarded to the mother, a principle rooted in social customs and maternal instinct.27Rawshanʹfikr 193 (Farvardīn 1336/April 1957): 25. She viewed this incident as indicative of a shift in Iranian society’s divorce dynamics. Whereas in earlier times, divorce was generally pursued by women from upper-class families, and resisted by middle- and lower-class women, the Jārʹallāhī case, driven by a woman of the middle-class, highlighted the growing spread of divorce-related challenges among women in the middle and lower strata of society.28Rawshanʹfikr 193 (Farvardīn 1336/April 1957): 25.

Nayyirah believed that girls, like boys, were fully capable of developing their talents, provided the right environment. In her view, the family played the most critical role in this development. Based on her observations and studies, she asserted that in families where girls had access to education and artistic opportunities, their talents could flourish, often equaling, if not surpassing, those of their male peers.29Rawshanʹfikr 126 (Day 1334/December 1955): 5.

She categorized the women of her time into three groups. The first were traditional women whose primary concerns were domestic duties and caring for their husbands. The second group consisted of Westernized women who had a superficial understanding of Western culture, associating it merely with following fashion trends. While Nayyirah did not oppose elegance and fashionable dress, she regarded fashion as merely a means toward loftier goals. The third group comprised modern women who actively pursued their rights and rejected any form of discrimination. These women sought education and excellence in arts and industry, cultivated their creative potential, and, despite their profession ambitions, maintained strong commitments to their families and commanded the respect of their husbands and children.30Sipīd va Siyāh 24 (Day 1334/January 1955): 40–41.

The Significance of the Event of Kashf-i hijāb in the Expansion of Women’s Freedoms

Nayyirah Saʿīdī regarded the unveiling decree of Day 17, 1314/January 8, 1936, as a pivotal event that helped Iranian women gain certain rights and correct erroneous traditions and perceptions about them. Politically, the decree created an environment between 1314/1936 and 1335/1956 that fostered the emergence of notable women journalists. It also opened pathways for women to attain university professorships in Iranian and pursue journalistic careers in Europe. Economically, women were able to move away from factory work and gain access to employment in government offices, retail, radio broadcasting, and acting. Nayyirah viewed the prohibition of child marriage at age nine as another significant outcome of this decree, although she maintained that other marriage-related laws, including those regarding polygamy, divorce, and child custody, continued to favor men. The decree also influenced public attitudes toward women, including their social interactions, mobility, and broader freedoms.31Rawshanʹfikr 178 (Shahrīvar 1335/September 1956): 6. Nevertheless, in a post-revolutionary poem, Nayyirah voices dissatisfaction that women’s dress, during the unveiling decree and other periods, was manipulated by those in power for political ends.32Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 19.

Nayyirah Saʿīdī’s Works

A) Poems

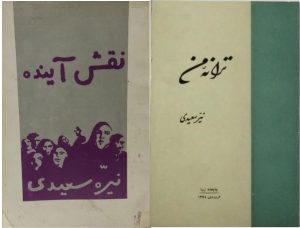

Nayyirah published poems in magazines such as Sukhan, Yaghmā, Gawhar, Ittilāʿāt, Vahīd and Bānū. She also released two poetry collections, Tarānah-ʾi man (My song) and Naqsh-i āyandah (The role of the future). These collections feature ghazal, qasīdah (from the root qasada, meaning “to aim at”—a formal, elaborate and often polythematic poem usually translated as “ode”), masnavī (literally “doubled,” a poem in rhyming couplets), tarjīʿʹband (literally, “return-tie,” a series of stanzas held together by a repeated refrain), qitʿah (literally “piece” or “segment,” a short, monothematic poem), chahārʹpārah (A poem consisting of several stanzas, each containing four hemistichs; typically, in each stanza, the second and the fourth lines rhyme) and modern-styled (naw) poetry.33Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 9.

Tarānah-ʾi man was self published and printed by Zībā printing house (Chāpʹkhānah-ʾi Zībā) in Farvardīn 1354/April 1975 and includes forty poems in different formats across eighty-three pages. Naqsh-i āyandah, which was printed by Naqsh-i jahān printing house (Chāpʹkhānah-ʾi Naqsh-i jahān) in 1369/1990, includes one hundred and thirty-five poems. Most of the poems from the first collection reappear in the second, albeit with new titles. Nayyirah Saʿīdī self-published this volume, indicating a lack of external support for her work.

Nayyirah’s major poetic themes include childhood memories, nationalism, love, women’s issues, regret, politics, moral instruction, and religious subjects. Her oeuvre also exhibits influences from classical Persian, French and English poets, making it a strong subject for comparative literature analysis.

Figure 4: Left: Nayyirah Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah. Tehran: Published by the author, 1369/1990. Right: Nayyir Saʿīdī, Tarānah-ʾi man. Tehran: Published by the author,1354/1975.

Memories of Childhood

Having experienced a secure and pleasant childhood with her parents and family, Nayyirah Saʿīdī consistently recalls that period with fondness. In her poem “Imrūz bāz yād-i tu mastam kard” (Today your memory intoxicated me again), she portrays childhood as a sanctuary from the turmoil of the world. Despite having encountered other lands and experiences, she ultimately prefers the alley of her childhood period, which, for her, offers a path to the world of meaning.

Today, your memory intoxicated me again

My heart, its wings freed, flew toward you again

It fled the hustle and bustle of the world

And came to pray in the corner of your retreat34Khvāndanīʹhā 60 (1327/1948): 48.

This poem was published in Vahīd magazine,35“Nayyirah Saʿīdī,” Vahīd, no. 123 (Isfand 1352/March 1974): 1243–45. and later appeared in the poetry collection Tarānah-ʾi man under the title “Kūy-i man” (My alley).36Nayyir Saʿīdī, Tarānah-ʾi man (Tehran: Self-published, 1354/1975), 3. It also reappeared in Naqsh-i āyandah as “Mahallah-ʾi Sarʹchishmah” (Sarʹchishmah neighborhood).37Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 32–33.

In the poem “Qissahʹhā-yi pīshīn” (Past tales) (1348/1969), Nayyirah nostalgically remembers her mother and childhood, asking her mother to once again tell the stories she used to recite of Khusraw va Shīrīn, Laylī va Majnūn, Shāhʹnāmah, Gulistān, Būstān, Masnavī and Hāfiz’s Dīvān:

Once again, tonight, like the youthful days of old

O mother, I yearn for a tale from you

Again, like the days of my childhood

I long for a heartfelt story from you38Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 13–14.

In the poem “Khātirāt-i madrisah” (Memories of school), Nayyirah recalls the joyful schooldays at the Jeanne d’Arc School:

I remember those days when we were carefree

Unaware of the whole wide world

But this nostalgic recollection ends on a somber note:

Now there’s nothing but hardship

There’s no time for compassion and sympathy39Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 61–62.

Regret for the Past

In Nayyirah’s poetry, a marked tension exists between the present and the past. She clearly favors the past, portraying it as a time imbued with innocence and intimacy, often set in the village amidst natural surroundings. In contrast, the present unfolds in vast, industrial, polluted cities that lack emotional depth. A tone of Romanticism pervades her work. This theme is prominent in the poem “Darīgh az guzashtahʹhā” (Alas for the past times):

I remember the world once felt like paradise

The sky was always blue

Each day sunny

Each night bathed in moonlight40Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 95–97.

In “Guzashtahʹhā” (The past times), Nayyirah begins by praising the beauty of her youthful self:

My face in youth was like a radiant moon

My stature adorned the garden like a boxwood tree

Nayyirah concludes with a poetic borrowing from classical poet Rūdakī (d. AH 329/941):

It wore me down and took with it every tooth I had41Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 108.

In “Bih yād-i javānī” (In memory of youth), written in 1365/1986, Nayyirah again expresses sorrow for her old age, alluding to a ghazal by Rahī Muʿayyirī.42Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 37–38. In “Amān az pīrī” (Beware of old age), she describes characteristics of her old age, including memory loss, interpreting the common Persian phrase Khudā pīrat kunad (May God grant you old age) as a kind of curse.43Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 110–12. In “Āyinah-ʾi sarguzasht” (The mirror of fate), she once more laments her lost youth, comparing signs of aging with her former vitality, ending with a poignant simile:

My eyes are the mirror of my fate

Look into my eyes and see what I’ve seen in the world44Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 34–35.

This nostalgia even extends to the city of Paris. In a poem titled “Pārīs” (Paris), Nayyirah laments that the city has forgotten its ancient traditions:

Paris, oh bride of the modern world

The freshness of the past no longer graces your face45Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 151–52.

Nayyirah’s poetry is also imbued with a persistent tone of melancholy. In the poem “Tarānah-ʾi gham” (Song of sorrow), she speaks of sorrow’s domination over her life, and declares that her heart no longer desires happiness:

Why is our nature accustomed to sorrow?

We’re serene only when we’re sad.46Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 99–100.

Nationalism

One of the central themes of Nayyirah Saʿīdī’s poetry is devotion to the homeland. Despite its challenges and imperfections, the homeland is portrayed as a place of peace and comfort. In the poem “Sawgand” (Oath), Nayyirah’s deep sense of Iranian nationalism is evident as she swears by all the sacred things:

The love of the homeland shall never fade

I swear by God, by my country, by the Qurʾān47Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 87–88.

In “Vatan-i man” (My country), which carries an epic tone, Nayyirah describes the country as the land of her ancestors, heroes, and the glories of Iran’s ancient history. She emphasizes that no foreign land can erase the memory of her homeland from her heart and tongue. She concludes the poem with the following lines:

Since the garment of my destiny was woven here

Let my shroud rot in this very soil48Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 40.

Yet, this wish of hers has never fulfilled, as her body was laid to rest in foreign soil.

In “Nisf-i jahān” (Half of the world, a traditional epithet for Isfahan), Nayyirah reacts angrily to the bombing of Isfahan by the Iraqi army. She laments the attack on her homeland, celebrates the city’s beauty and historical significance, and denounces the enemy’s brutality. She asserts the necessity of continuing the war until the invaders are repelled and expresses frustration with the indifference of other nations to this aggression.49Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 108.

In “Ay vāy bih man” (O, woe is me!), composed in 1365/1986, Nayyirah declares her willingness to sacrifice her life for the country in fight against the enemy:

Give the command and we shall lay down our lives

We are your children, O motherland

Do I stand here while the enemy threatens you?

O, woe is me, O woe is me!50Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 64.

In “Sarmāyahʹhā-yi jāvidān” (Everlasting wealth), Nayyirah extols the cultural and artistic heritage of Iran, citing Persepolis, the works of the painters such as Kamāl al-Mulk (d. 1319/1940) and Bihzād (d. AH 942/1535), Kerman carpets, the tilework of Shaykh Lutf-Allāh Mosque, and the shrine of Imām Rizā in Mashhad as enduring symbols of Iranian identity.51Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 49–50.

In “Bāz āmadam” (I have returned), Nayyirah responds to literary friends in Tehran who had composed some poems expressing their longing during her time in France. She explains her return with these lines:

No cure for my pain but the soil of a beloved land

I returned to my homeland seeking remedy52Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 193.

In “Āvārah” (Wanderer), composed in Paris, Nayyirah gives voice to her longing for her homeland:

My heart is captive to the sorrow of exile

Like a weary bird, far from blossom and meadow53Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 92.

Nayyirah’s spirit is deeply restless: in Iran, she laments the absence of her children; abroad, she yearns for home. In the poem “Tabʿīdī” (The exile), she depicts a dialogue with a French neighbor. She likens herself to the parrot in Rūmī’s Masnavī-yi maʿnavī, who longs for her native land:

Speak to me of my homeland

These gardens I gladly leave to you54Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 38–39.

Nayyirah also composed the poem “Daʿvat bih vatan” (Invitation to the homeland) for her daughter, who, after completing her studies in France, invited her mother to join her abroad. In response, Nayyirah, in a motherly and affectionate tone, reminds her daughter of the value of the homeland and the sacrifices made by previous generations to preserve and build it. She urges her to return quickly, so that the country may not be left empty of its youth, for if that were to happen, it would become “a lair for leopards and lions.”55Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 71–74.

Women

Just as women were one of Nayyirah Saʿīdī’s primary concerns in her social and political activism before the Islamic Revolution, also occupy a prominent place in her poetry. In the poem “Naqsh-i āyandah” (The role of the future), which also lends its name to her most important poetry collection, Nayyirah envisions the future role of women as centered on the pursuit of knowledge and art, the cultivation of character, humility, patriotism, chastity, and gentle speech.56Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 11–12. In “Mard kīst” (Who is a man?), she writes:

Many a woman, more courageous (literally, “more of a man”) than men

Charges into danger like a lion

If a woman is self-possessed and virtuous

In times of trial, she surpasses men

In this poem, Nayyirah defines “manhood” not by gender but by qualities such as dignity, bravery, and discretion. Accordingly, if a woman possesses these traits, she is “more of a man” than any man.57Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 145–46. She thus interprets the Persian word mard (“man”) in cultural and literary contexts as signifying a set of virtues rather than a biological identity: Anyone who embodies these virtues deserves the title, while anyone who lacks these virtues, regardless of gender, does not.

In “Vafā-yi zan” (Woman’s faithfulness), Nayyirah tells the story of a self-sacrificing mother to argue that women are inherently more faithful than men. By reversing the traditional roles of Shīrīn and Farhād, she asserts that even in love, women display greater loyalty:

In love, she is Farhād,

The one who gave her sweet life58Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 85–87.

In “Az band rastah” (Freed from the chains), written before the Islamic Revolution (1353/1974), Nayyirah begins by portraying the previous generation of women as confined to domestic “cage,” then contrasts this with contemporary women’s access to freedom and progress. Yet she ultimately expresses nostalgia:

Though we have escaped the nest, we see

That nest was a haven of love

Though we are free from the chains, alas

Those chains were made of love and friendship59Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 42.

In “Har lahzah bih shiklī” (At every moment, a different shape), composed in 1365/1986, Nayyirah critiques the politicization of women’s clothing. She observes that before Nāsir al-Dīn Shāh Qajar, women were the traditional chador and veil. However, after his trip to Europe, where he admired Western fashions, he introduced Western styles to his court. She then indirectly refers to Reza Shah Pahlavī’s mandatory unveiling and criticizes the coercion of women into removing their traditional garments. After the Islamic Revolution, yet another dress code was imposed. In all these periods, Nayyirah argues, women were compelled to follow political dictates. She openly criticizes this dynamic:

Why is it that, time and again

Our clothing is entwined with politics?

At the poem’s end, Nayyirah affirms that Islamic law should determine proper dress, though it remains unclear whether this reflects a sincere ideological shift or a post-revolutionary concession.60Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 18–20.

After the revolution, some of Nayyirah’s poems adopt a more religious tone. In “Fakhr-i zanān” (The pride of women), composed in 1369/1990, she praises Fātimah, the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad, as the ideal woman. Enumerating her virtues—goodness, sincerity, chastity, loyalty, sympathy and compassion—, she presents her as a timeless role model:

That woman who embodied all womanly worth

A radiant model of feminine brilliance

She who rejected disgrace and humiliation

The guiding light of women’s lives61Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 16–18.

In contrast to the classical traditional language and themes that characterize most of her poetry, some of Nayyirah’s later poems adopt a more intimate, feminine tone. In “Khastah shudam” (I’m tired), she expresses the exhaustion of a woman overwhelmed by the burdens of daily life:

I’m tired of everywhere, of everyone

I’m tired of the whole world

The same theme recurs in “Gham-i nāʹshinās” (The unknown grief), where a woman is consumed by inexplicable sorrow:

No heart is as broken as mine

I’m weary of the sorrow and suffering that I cannot name62Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 41.

In another instance, while serving as a member of the parliament, Nayyirah was deeply moved by a bill proposing the removal of pigeons from airports due to aircraft collisions. She wrote a poem addressing the pigeons with empathy, defending their right to freedom as the ancient and rightful dwellers of the sky:

As long as God wills your freedom

The sky remains your ancestral home63Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 53.

Nayyirah’s poems also reflect maternal tenderness. In “Āghāz-i ranj” (The beginning of suffering), she finds her daughter awake past midnight, holding a book but visibly lost in thought. Nayyirah imagines a quiet, inner dialogue with her adolescent daughter.64Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 22–24. In “Fānūs-i rāh” (The lantern of the path), composed in 1352/1973, she voices concern about her daughter’s future, warning her about the deceitfulness of the world and the unfaithfulness of people. Yet she ultimately concedes that such lessons must be lived to be learned:

Until you take counsel from life itself

You will not learn from anyone’s advice65Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 97–99.

In “Sarbāz-i gumʹnām” (The unnamed soldier), written in 1365/1986, Nayyirah confides in a soldier about her separation from her children, portraying the pain of a mother enduring absence.66Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 29. The same theme appears in “Chishmʹintizār” (Awaiting) in which a mother, anguished by her child’s prolonged silence, longs for a letter or photo and expresses a willingness to sacrifice anything for her children’s well-being in France:

I will sell everything, no matter the cost

To free your souls from the chains of sorrow67Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 54–55.

A prose-poem titled “Pāsukh-i farzandam” (My child’s response) found in the collection Naqsh-i āyandah, is written from her daughter’s perspective. In it, the daughter describes her difficult life working in a French café.68Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 55–57. Similarly, in the poem “Dukhtar-i dukānʹdār” (The shopkeeper girl), Nayyirah, speaking as a wise and affectionate mother, tells her daughter, who works as a shopkeeper, that her dignity and bearing deserve more.

Such dignity and poise exceed a shopkeeper’s lot

Why do you say you’ve spent years behind the counter?69Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 58–59.

In “Fāl-i Hāfiz” (Hāfiz’s divination), she instructs her daughter in the ways of love and choosing a companion, drawing on the poetry of Hāfiz (d. AH 792/1390) for wisdom and guidance.70Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 81–82.

Among the few women to whom Nayyirah dedicates a poem is Parvīn Iʿtisāmī (d.1320/1941) Being under the influence of Parvīn in her qitʿah and munāzirāt (dialogic poems), Nayyirah introduces this prominent contemporary woman poet in this way:

The pride of the nation’s women

She still holds that exalted status

Nayyirah’s exceptional praise stems from her desire to present Parvīn as a role model for Iranian girls. In this poem, she highlights various aspects of Parvīn’s persona, including her literary talents, learning, defense of the oppressed, defiance of tyrants, and resistance to excessive materialism. Nayyirah believes that Iranian girls should cultivate these same virtues in themselves.71Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 83–84.

Love

Love is one of the recurring themes in Nayyirah’s poetry, appearing across her entire oeuvre. While she largely draws on classical Persian imagery and metaphors such as the captive heart-bird in the beloved’s alley, the mad lover tamed by the chains of the beloved’s curls (“Dil-i dīvānah,” or Mad heart), the anonymous homeless lover (“Bi-āshīyān” or Homeless), and the lover’s gold refined in the beloved’s fire (“Tughyān” or Rebellion), she introduces some original nuance in “Nīmah-ʾi gumʹshudah” (The missing half). Inspired by Plato, she depicts love as the human quest for completion:

You are my missing half; I have been parted from you all my life

You seek someone like me, and I had been seeking you72Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 26–27.

Politics

Political themes are rare in Nayyirah’s work, especially after the Islamic Revolution, where her voice takes a more conservative tone. Nonetheless, critique of authority emerges occasionally. For example, in “Hanūz ham hastand” (They still exist), composed in 1364/1985, she critiques the society of her time, denouncing poverty, tyranny, injustice and corruption:

Accused of speaking the truth

Enemies of tyranny

Still stand behind prison bars73Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 35–36.

In “ʿAdl-i ʿAlī” (ʿAlī’s justice), which was composed in 1362/1983, Nayyirah begins by praising Imām ʿAlī ibn Abī-Tālib’s justice, recounting stories of his fairness and equity. She then rebukes the revolutionary course of the early post-revolutionary period:

Beware lest you pass judgment without a fair hearing,

If the cause of the crime remains unknown.

Better that a vile and wicked criminal

Escapes the grip of justice

Than you should see by your command

The head of an innocent raised on the gallows74Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 47–48.

In “Lahzah-ʾi dīdār” (The moment of meeting), composed in 1364/1985, Nayyirah yearns for the moment of her death, seeing her life as one of sorrow and exhaustion:

The precious goods of art had no buyers,

Like faulty wares, we were abandoned in the market’s corner75Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 48–49.

While living in France, upon witnessing on television the bombing of Iran by Iraqi aircraft, Nayyirah composed a fervent poem titled “Dar havā-yi vatan” (Thinking about the homeland) in 1366/1987. In this poem, she criticizes the leaders of the country and says:

The ship of Iran has fallen into stormy waves

Has the eye of the homeland’s captain fallen asleep?

In this way, she implies that the leaders do not appreciate the true value of the homeland:

One who, like me, is today far from that soil

Knows better the worth and price of the homeland76Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 68–69.

In a note accompanying her poem “Shikāyatī bih dādʹsarā” (A complaint to the prosecutor’s office), written in 1364/1985, she recounts a personal incident: the vault ceiling of her home collapsed in 1364/1985 due to construction work at the adjacent prosecutor’s office. Again, in 1366/1987, leaking water from the building’s air conditioning system caused water damage to her house. She complains that although she expected—due to her proximity to the office—to be protected from injustice, she experienced injustice from that very institution. She writes:

To whom shall I complain?

No one would hear my pleas

They suppose that I’m just a fool in this neighborhood77Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 88–89.

In another poem titled “Dādʹsitān” (The prosecutor), composed in 1366/1987, Nayyirah complains about the injustices she suffered after the Islamic Revolution. She mourns the confiscation of her property, the destruction of her reputation, and the unjust attribution to her of crimes committed by former government officials. She describes the severity of her situation and the fact that nothing remains for the authorities to seize.78Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 115–17. In a note to her poem “Jurm-i āshkār” (Blatant crime), written in 1359/1980, Nayyirah says that a group identifying themselves as guards and members of the Basīj (pāsdār va basījī) and military personnel, who were later revealed to be a gang of thieves and murderers, stormed her home. In the poem, she describes the violations and assaults committed by these groups during the early days of the Islamic Revolution, particularly those associated with the previous regime:

Who are you? By whose orders have you come into my home?

You drag from the house all who are close to me

What you tear in anger are not the portraits and writings of kings

They are my husband’s letters, the images of my beloved79Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 154–55.

In “Hamāhangī” (Coordination) (1374/1985), a group of Iranians exiled abroad gather to discuss the situation in Iran. However, each speaker negates the others with the prejudice of their own perspectives and ideologies, and the gathering descends into dispute and discord. In the midst of this, a figure representing wisdom raises his voice:

When a nation is not in harmony with each other,

It only deserves riots and wars

In the end, he prays:

May all Iranians from every corner

Gather again in this land

To rebuild this house anew

And drive the foreigner from this soil80Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 141–44.

Religious subjects

Some of Nayyirah Saʿīdī’s poems, especially those written after the Islamic Revolution, feature religious and Islamic figures and concepts. In the poem “Zāmin-i āhū” (The guarantor of the gazelle), composed in 1361/1982, she recounts the story of ʿAlī ibn Mūsa al-Rizā, the eighth Twelver Shīʿī Imām, and how he became the guarantor of a gazelle to a hunter. At the poem’s conclusion, she asks the Imām to intercede for her as well, so she might be granted the chance to visit her daughters living in France.81Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 14–16.

Advice and Moral Counsel

Following the tradition of classical Persian poets such as Firdawsī, Saʿdī and Rūmī, Nayyirah Saʿīdī uses her poetry to invite readers toward ethical living, an understanding of the world, and appreciation of human values. She conveys these messages through narratives and dialogues voiced by historical figures. For example, in the poem “Kalām-i Suqrāt” (The words of Socrates), she speaks through the voice of the Greek philosopher to highlight the rarity of sincere friendship.82Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 24–25. In “Firīb” (Deception), she warns against being deceived appearances, emphasizing the stark difference that can exist between a person’s outer image and their inner reality:

If you tear away the many veils from their faces

You’ll find demon hearts beneath angelic faces83Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 85.

The Role of Classical Persian Poets in Nariyyah Saʿīdī’s Work

Thanks to her academic training and decades of deep literary studies, Nayyirah Sāʿīdī’s poetry is rich in allusions, quotations, and references to Persian language and literature. For example, in “Yik ʿumr bā Hāfiz” (A lifetime with Hāfiz), she speaks directly to the poet and describes him and his Dīvān (collection of poetry).84Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 45–46. In “Munājāt” (Supplication), she imitates a poem by Mawlānā; in “Naqsh-i āyandah” a poem by Nāsir Khusraw;85Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 11–12. and in “Daʿvat bih vatan” a poem by Firdawsī.86Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 71–74. In “Qissahʹhā-yi pīshīn,” she makes allusions to literary masterpieces such as Nizāmī Ganjavī’s Khusraw and Shīrīn (Khusraw va Shīrīn), Firdawsī’s The Book of Kings (Shāhʹnāmah), Hāfiz’s Dīvān, and Saʿdī’s The Rose Garden (Gulistān) and The Orchard (Būstān).87Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 13–14. While describing or even criticizing literary societies, Nayyirah stresses the need to revive the Persian language:

If Persian language is revived

Its glory shall be ours to claim88Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 117–19.

In the poem “Shāʿir-i jāvidānah” (The eternal poet), she emphasizes Firdawsī’s unique role in preserving Persian and recounts his moral counsel for readers:

Firdawsī, the founder of Iran’s history

No era’s eyes have seen his equal

If women earned status in this land’s history

It is from him they gained rank, worth, and title89Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 146–48.

In “Nīrū-yi shāʿirān” (The power of poets), Nayyirah once again invokes poets and literary monuments, portraying poets as the very forces that have kept the name of Iran alive and breathed new life into its history. She writes:

If the Persian language has endured in the world

It is through your words like pearls and coral that it survives90Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 70–71.

Engaging in poetic debate (munāzirah) with other poets is among Nayyirah’s literary pastimes. In one instance, she composes a verse exchange with the contemporary poet Abū al-Hasan Varzī regarding the idea of hosting a gathering.91“Zan dar munazirah-ʾi sih shāʿir-i muʿāsir” [Woman in the debate of three contemporary poets], Gawhar 43, (Mihr 7, 1355/September 29, 1976): 554–55. Another example comes from one of the ikhvāniyyat (friendly correspondences between two literary figures, whether in prose or verse) shared between her and Mahmūd Farrukh. In this poem, Farrukh critiques Nayyirah for encouraging women to dress stylishly and wear make-up to charm men. Nayyirah replies by clarifying that by “charm” she does not mean violating purity and chastity but rather refers to a kind of allure that stimulates poetic inspiration. She writes:

If a gazelle does not know the art of charm

She would charge forward when she should flee

According to Nayyirah, feminine allure is not about reckless exposure to danger, but rather a tool by which women can withdraw from perilous situations when necessary.92“Zan dar munazirah-ʾi sih shāʿir-i muʿāsir” [Woman in the debate of three contemporary poets], 554–55.

Comparative Literature

Nayyirah Sāʿīdī’s poetry may be fruitfully examined through the lens of comparative literature, particularly the French school of the discipline. This school emphasizes two key criteria: the difference in language between literary works being compared, and the necessity of a demonstrable historical relationship between them.93Pierre Van Tieghem, La littérature comparée, 4th ed. (Paris: A. Colin, 1951), 43. Nayyirah’s familiarity with French language and literature, along with her translations of works by Jean de La Fontaine (1621–1695) and Stefan Zweig (1881–1942), makes her poetry especially suited to such comparative analysis.

In notes accompanying several of her poems, Nayyirah explicitly acknowledges her indebtedness to La Fontaine’s tales. One such example is the poem “Shukūh-i tāvūs” (The magnificence of the peacock).94Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 102–3. In “Āyā khabar dārī” (Do you know?), she openly states that the poem is a poetic adaptation of a work by Baudelaire, and emphasizes her attempt to replicate the rhythm and musicality of the original.95Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 90–92. Similarly, her poem “Javānʹmardī” (Chivalry) is derived from a piece by Victor Hugo.96Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 169–70. In “ʿUmr-i shabnam” (The life of the dew), she translates “To Daffodils” by the seventeenth-century English poet Robert Herrick into Persian verse. This translation was published in the literary magazine Sukhan and was awarded a prize for the best translation. Her work on this English poem reveals her fluency in the English language and further supports an analysis of her poetry considering English literary influences.97Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 75–76.

Imagology is another area within comparative literature that can be applied to Nayyirah’s work. This field examines how one nation or its people are represented in the literature of another. Given Nayyirah’s extensive travels, and especially her long-term residence in France, her depiction of France and the French in her poetry invites imagological analysis. Poems such as “Pārīs” (“Paris”) offer particularly rich material for this approach. First, the image she presents of Paris is a direct one, shaped by her immediate observations and firsthand experiences of the city. Second, her evaluative attitude toward Paris is clearly discernible. Phrases such as “the bride of the world” and “the fading of former freshness” reflect her evolving perception of the city over time and allow for a nuanced reading of her shifting perspective.98Saʿīdī, Naqsh-i āyandah, 101–2.

B) Translations

Translation constitutes one of the central pillars of Nayyirah Sāʿīdī’s scholarly and literary endeavors. Her translated works include poetry and prose from both French and English literary traditions. A number of these translations appear in her collection Naqsh-i āyandah. In addition to these, she produced a full-length, metrical translation of La Fontaine’s poetry.99Jean de La Fontaine, Qissiʹhā-yi Lā Funtayn [Tales of La Fontaine], trans. Nayyirah Saʿīdī (Tehran: ʿIlmī va farhangī, 1367/1988). This translation was so well-received that it was awarded a UNESCO prize. Another body of Nayyirah’s translations involves fiction, The Royal Game also known as Chess Story (Shatranjʹbāz) and Casanova, both by Stefan Zweig. She also translated several French plays and performed them on radio and on stage. Among them is the play Shab-i buhrānī (A night of crisis), which exemplifies her engagement with dramatic literature in translation.100Ittilāʿāt-i bānuvān (Tehran), no. 188 (Āzar 07, 1339/November 28, 1960), 5.

C) Academic Articles

Nayyirah Sāʿīdī’s articles that are available to us are mostly review-style and journalistic essays on a range of subjects published in various periodicals. They address different subjects, including literature, women’s poetry, and women’s social rights. One of her more notable articles, titled “Sukhanī chand bā dūstʹdārān-i tiʾātr” (A few words to theatre enthusiasts), stems from her formal education in dramatic arts in France. In this piece, she outlines the key principles of acting, such as natural performance, facial expression and tone, movement, and the role of silence.101Nayyarah Saʿīdī, “Sukhanī chand bā dūstʹdārān-i tiʾātr” [A few words to theatre enthusiasts], Sukhan, no. 9 (Day 1336/December 1957): 887–90.

D) Interviews

Several interviews with Nayyirah Sāʿīdī appeared in magazines of the time such as Ittilāʿāt-i bānuvān (Ladies’ news), Rawshanʹfikr (The enlightened) and Sipīd va sīyah (White and black). All of these interviews were conducted before the Islamic Revolution. In them, she responds to questions about her personal life, professional activities, and matters related to women’s rights and contemporary events.

A documentary film titled Nayyirah, Surūdʹhā-yi āzādī (Nayère, Les Chants de Liberté), produced by her daughter, Mīnā Saʿīdī, was also made. The film was created during Mīnā’s journey to Iran and consists of interviews with her mother’s relatives and close acquaintances. It features conversations with prominent women such as Sīmīn Bihbahānī, Shahlā Shirkat and Shīrīn ʿIbādī, and not only chronicles Nayyirah’s personal life but also sheds light on the social and political environment of her era.

Conclusion

Nayyirah Saʿīdī’s social and literary life can be divided into three distinct periods. The first spans from her childhood to her marriage with Muhammad Saʿīdī. Considered by her the happiest phase of her life, it was marked by the nurturing environment of a poetry- and culture-loving family. During this time her poetic talents flourished, and her education at one of Iran’s top schools enhanced her intellectual development, particularly her understanding of Western modernity.

The second period begins with her marriage and continues until the Islamic Revolution. During these years, Nayyirah traveled extensively across Europe and lived for an extended time in France. After earning her degree from the Sorbonne, she returned to Iran with passionate ideas about and a strong commitment to women rights. She served two terms as a representative for Tehran in the National Consultative Assembly and actively participated in numerous organizations devoted to women’s issues. Her advocacy appears in her poetry, interviews, and public speeches, on behalf of Iranian women.

The third and final phase of Nayyirah’s life begins with the Islamic Revolution and ends with her death in Paris. During this time, she withdrew from public political and social life and lived in seclusion. Nevertheless, this was her most prolific period as a poet. In addition to themes of homeland, womanhood, childhood memories, sorrow, and regret, her poetry increasingly incorporated moral reflections and religious motifs.

In sum, although Nayyirah Saʿīdī’s poetry may not match the structural, aesthetic, or innovative achievements of leading female poets of her time, such as Parvīn Iʿtisāmī or Furough Farrokhzad, what sets her apart is the extensive scope of her political and social engagement, particularly in the realm of women’s rights. Indeed, no other female poet of her time or afterward is known to have been elected twice to the National Consultative Assembly by securing a significant share of votes from the capital’s electorate, thus becoming a prominent voice for women within Iran’s highest political and social institutions.