Iranian Armenian Poetry: Sonia Balassanian Crossing Borders of Consciousness

“Border art deals with shifting identities, border crossings, and hybridism,” —Gloria Anzaldúa1Gloria Anzaldúa, “Border Arte: Nepantla, el Lugar de la Frontera,” in The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader, ed. AnaLouise Keating (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 184.

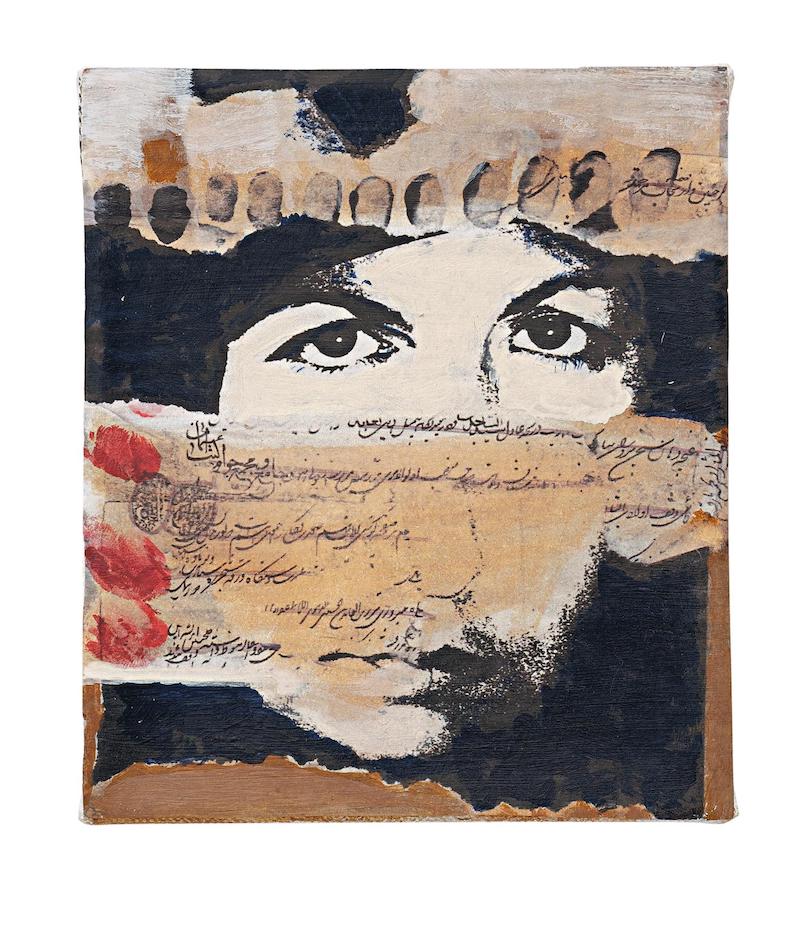

Born in Iran, Sonia Balassanian is a visual artist and poet who currently lives in New York and Yerevan, and writes in Armenian. She holds a BFA from the joint program of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the University of Pennsylvania, as well as an MFA from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York. She is also an alumnus of the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program. Between 1970-1979, Balassanian taught art in the College of Fine Arts, Milli University, and Farabi University in Iran. While she had been a successful artist and poet in Iran, Balassanian’s life changed after the 1979 revolution. She left the country for good. Not only did this move impact her life, but it also left marks on her body of work. Thereafter, Balassanian became more concerned with sociopolitical issues, women’s rights, and social justice.2Sonia Balassanian, “Borders of Identity,” July 14, 2010, www.soniabalassanian.com/borders-of-identity/. Stripped of her country, language, and identity in Iran, she endeavored to find her hybrid cultural heritage within her creativity and imagination while simultaneously attending to topics such as global suffering and pain. Crossing physical geographical borders (the move to New York) allowed Balassanian to move subjective borders within her consciousness. She faced a shift in her perspective—that of the personal, the political, and of social justice. In this brief piece, I will discuss Balassanian’s poetry in the context of that shift. I will provide examples from her poetry where she addresses questions of physical borders and identity, spiritual borders, crossing borders, and global pain and suffering. I will demonstrate how in all her poems, we can also find traces of her artistic sensibility through her use of diction, imagery, metaphors, and symbolism. However, before I delve further into Balassanian’s poetry, it would not be out of place to briefly discuss Iranian Armenian poetry and its development. Prior to reaching its peak in the nineteenth century, Iranian Armenian literature was limited to the creations of troubadours and songwriters—the so-called Armenian Ashuqs, for almost a century. Julfa in Isfahan was the center of the community and its cultural production. In the nineteenth century, the literary transformations of the Caucasus and Russia, as well as the literature of other Armenian immigrants, greatly influenced Iranian Armenian literature. After the Constitutional Revolution, the arrival of a number of Armenians from the Caucasus to Iran contributed to the foundation and emergence of a new generation of Armenian authors. Thereafter, literature, especially poetry, began evolving, and Armenian poets succeeded in writing poetry which was influenced by the works of Huvhanis Tumanians, Yiqishi Charints, Avidik Isahakian, and Vahan Dirian. From then on, Armenian poetry continued to develop in two trends: the poets who believed in maintaining the old tradition of Armenian poetry, and those who, while following the tradition and enjoying it, presented their works in new forms as well.3Hrand Ghukasian, “Ishari-yi bi adabiyat-i Aramanih dar Iran” (A Brief Study of Armenian Literature in Iran), Armaghan 39, 9 (1970), 623–4. Many factors contributed to the flourishing of Iranian Armenian culture and literature. The existence of several associations, such as the Cultural and Artistic Society of Armenians in Tehran; the Armenian Women’s Association of Hay Gin; the Association of Armenian Students of Tehran University; the Charity Association of Armenian Women of Tehran, and those in Isfahan such as the Association of Youth Culture of Julfa; the Association of Armenian University Students of Isfahan; charitable associations of women supporting the impoverished and the poor; NGOs; and many cultural centers, as well as various associations in Tabriz, were of outmost significance. The establishment of an Armenian language and literature major at the University of Isfahan contributed to the expansion of Armenian literature to a great extent. More importantly, the Armenian Writers Association of Iran, which was formed in 1961 with thirty members, was influential. Most of the members of the association were well-known writers and poets. The press and journalistic publications, such as the Alik newspaper, which has been published and disseminated since 1931, played a major role. The majority of Iranian Armenian writers and poets collaborated with this newspaper at some point. The Alik monthly magazine, which was part of the Alik newspaper, was mostly artistic and literary. Alik for adolescents was a journal that had a great impact on the development of young people’s thoughts. The literary journal and group, Nur Ij (lit. New Page) began its work in 1932, had a founding board of seven authors such as Markar Qarabigian (also known as Div), Ashut Aslanian (also known as Aslan), Hrand Falian (the founder of the group), Galust Khanints, Giqam Mgirdichiān, Ara der Huvhanisian, and Arshavir Mgirdich.4Edic Baghdasarian (also known as Ed. Germanic), Nigahi bi tarikh-i Armanian-i Tihran (A Short Glance at the History of Armenians in Tehran) (Tehran: Arax Monthly, 2002), 14-6. Later, other members also joined the group such as Zurik Mirzaian, Rubin Avanisian, and Frangian. In addition to poems, stories, and articles, Nur Ij published works from world literature and scholarship, including those by Iranian authors, translated in the Armenian language.5Ghukasian, “Ishari-yi bi adabiyat-i Aramanih dar Iran,” 620-2.  Balassanian began writing poetry at the age of twenty-three in 1965 when she got involved with the Armenian literary group Nur Ij in Tehran. She became an official member of the group in 1971 and published a poem in the eighteenth volume of the journal in 1975. This publication cemented her fame as a poet. Balassanian has published two books of poetry titled, Maybe Once a Crazy Heart and Granting Emotions Full of Dreams to the Roar of Rain, in New York. The two books have also been published in Yerevan in a single volume. In 2022, these two books, titled The Roar of Rain, were translated in the Persian language in a single volume in Tehran. In a section titled “Borders of Identity” on her website, Sonia Balassanian writes about her journey to historic Armenia (now eastern Turkey) in the summer of 2009 as part of her long-standing fascination with borders. During this trip, many thoughts and questions crossed her mind, including, she confesses, the following: “Are there borders of identity? Can one cross them? Can one distinguish where one stops and the other starts? Is a mixture of layers of identity possible in a time like ours?” In addition to these questions, she wrote the short poem below during the trip where she considered herself as a shadow of the past and the present, between identities and nations:

Balassanian began writing poetry at the age of twenty-three in 1965 when she got involved with the Armenian literary group Nur Ij in Tehran. She became an official member of the group in 1971 and published a poem in the eighteenth volume of the journal in 1975. This publication cemented her fame as a poet. Balassanian has published two books of poetry titled, Maybe Once a Crazy Heart and Granting Emotions Full of Dreams to the Roar of Rain, in New York. The two books have also been published in Yerevan in a single volume. In 2022, these two books, titled The Roar of Rain, were translated in the Persian language in a single volume in Tehran. In a section titled “Borders of Identity” on her website, Sonia Balassanian writes about her journey to historic Armenia (now eastern Turkey) in the summer of 2009 as part of her long-standing fascination with borders. During this trip, many thoughts and questions crossed her mind, including, she confesses, the following: “Are there borders of identity? Can one cross them? Can one distinguish where one stops and the other starts? Is a mixture of layers of identity possible in a time like ours?” In addition to these questions, she wrote the short poem below during the trip where she considered herself as a shadow of the past and the present, between identities and nations:

I am a shadow of my past and present, between identities and countries. How can I cross these boundaries, these borders, these lands?6Balassanian, “Borders of Identity.”

However, this was not the first time Balassanian was pondering the question of identity and borders. In 1985, about twenty-five years before traveling to historic Armenia, and during the peak of Iran-Iraq War (1980-88), she had written another poem of similar significance:

We think about the miracle of life of earth, sun, light.

We destroy circumferences Erase the borders.

They suffocate the light, In madness, pound the steel chains, Constrain the laughter of the earth, Close the shutters of the sky, Erase the windows blue, and encircle themselves in the spider’s web.

Mounted on hurricanes of the world We dash into the suns of light …7Sonia Balassanian, Yirku Girk Banastightsutyun (Two Books of Poems) (Yerevan, Armenia: The Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art, 2006), 195

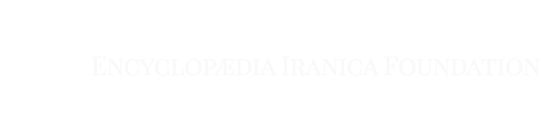

Immersed within the world of borders and questions of hybridity, Balassanian disrupts hegemonic discourses around separatism and nationalism and moves beyond borders. She finds borders suffocating and encourages us to destroy them. For her the border lines which are drawn to separate “us” from “them” are sites rife with possibilities and growth. As Gloria Anzaldúa, the Chicanx Cultural theorist, writes, the “border is a site where many different cultures ‘touch’ each other, and the permeable, flexible, and ambiguous shifting grounds lend themselves to hybrid images. … By disrupting the neat separations between cultures, they create a culture mix, una mezcla in their artworks. Each artist locates her/him self in this border ‘lugar,’ and tears apart and rebuilds the ‘place’ itself.”8Anzaldúa, “Border Arte,” 177. This is exactly what Sonia Balassanian does in her art and poetry.

Similarly, in another poem, she calls for a mobilization to move beyond borders:

Similarly, in another poem, she calls for a mobilization to move beyond borders:

Moving beyond the universe, Walking in the sun … Destroying the borders, Walking. Riding on a fiery dream Drumming on the sun’s stretched skin … Around the beehives Whirling, dancing … Walking toward the sound, Knocking on strangers’ doors, Kissing the thirsty lips … Moving beyond the borders, Laughing, Crying, Praying, For a handful of soil.9Balassanian, Yirku Girk Banastightsutyun, 194

Destroying the borders is liberating for Balassanian. It opens gates for embracing strangers whether the individuals themselves be strange or their perspectives. However, it would be simplistic and limiting to consider Balassanian merely as a border artist/poet. In all her works, Balassanian does more than crossing borders and shifting identities. In addition to physical borders, she crosses borders of the mind, consciousness, and spirit.

Balassanian’s poetry is multilayered with internal depth, full of mental images and overt and inner sensibility. Since she is also a visual artist, the interaction of poetry and imagery in her works has led to a wide range of forms of expression and scope. In her first book, Balassanian attends to surrealist ideas; in fact, she speaks about her own personal emotions which are expressed via symbolism and metaphors, so they seem to lack any rationale. A poignant example of such symbolism from Balassanian’s first book can be found in the following poem where she allows readers to get a glimpse of her inner world.

Victims Victims Victims

Cities are dying, Cities are born … I want to destroy everything … My blood is boiling in my veins, The rays of the sun are exploding, Hearts … The world is exploding Bombs … The night is unsafe Dark … The existence is revolving In the square-shaped frames … Victims, Victims, Under the walls of Rootless cities.10Balassanian, Yirku Girk Banastightsutyun, 84.

Balassanian’s poems are sprinkled with the literary device of personification where she prescribes human qualities and features to inanimate objects, plants, or animals, further contributing to abstraction and surrealism. Take for instance cities which are “dying and being born” and the sun and the world which are “exploding” in this poem. The result of such animation is a poem full of imagery, just like a painting. This poem, however, has multiple layers of visual significance whose impact is not limited to its play of words or personification. The poem also has a strong visual effect with its composition and organization of lines which are constricting and expanding, just like the cities that are dying and being born, and the sun and the world, which are exploding. For instance, the visual imagery of the final four lines is that of a descent—a descent to “under the walls of rootless cities.” Placing the words on the paper, Balassanian’s pen is functioning like her brush on the canvas. Visual imagery, personification, diction, organization, and composition merge to convey the same visual and sensual message, that of suffocation.

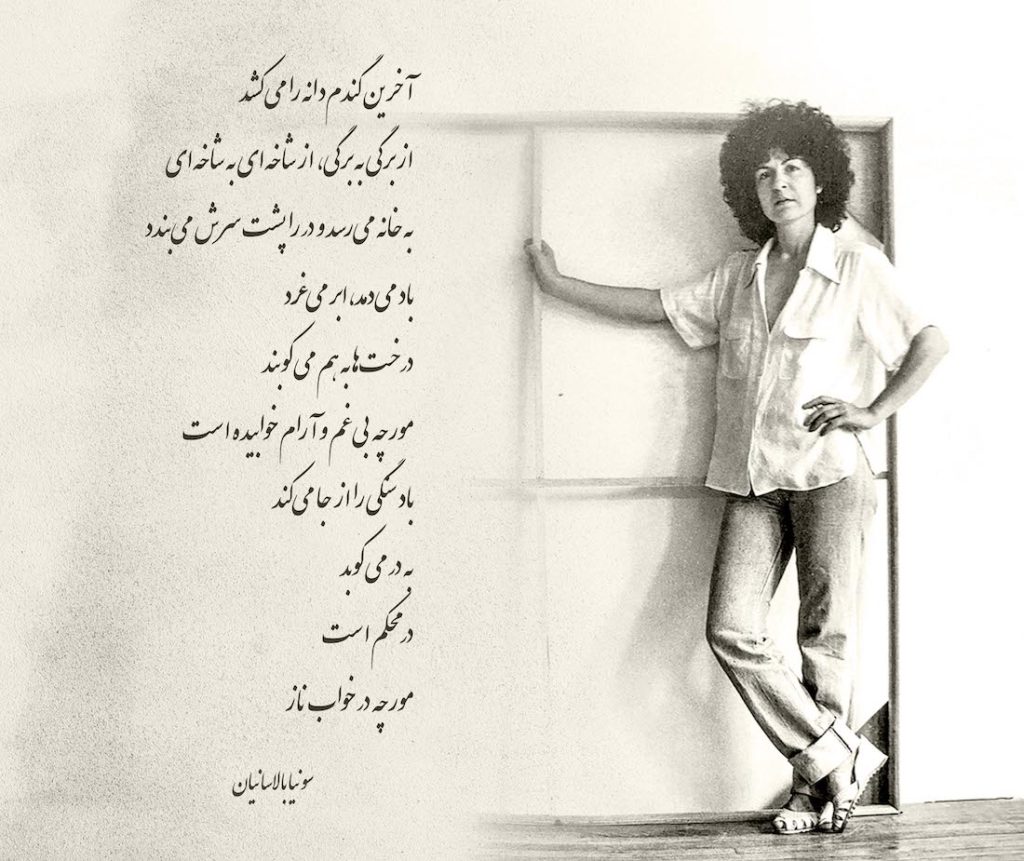

In her second book, Balassanian intentionally replaces the personal with the collective or the global. She focuses on urban and rural life, as well as national and family rituals and traditions with a touch of social critique. However, the metaphorical, the symbolic, and the visual elements from Book One remain untouched and carry over into Book Two. Balassanian’s second book is pregnant with childhood memories and references to an unattainable past. According to Edward Balassanian in the preface of the Roar of Rain, “Balasanian, the painter, has an interesting presence in the work of Balassanian, the poet. Allegorical or direct expressions of her poems are often emphasized or complemented by visual elements such as scene, shape, color, line and the play of light.”11Balassanian, Yirku Girk Banastightsutyun, 84. What Edward Balassanian refers to regarding the play of light and colors is explicitly crystalized in the following poem:

From darkness to light From light to darkness I fluctuate from color to color From light to light … My word spreads from border to border The colors are thickening, Becoming bolder, highlighted. I am drunk, Laughing, weakening. My word shorter, becomes a dot, Lost in the streaks of light …12Balassanian, Yirku Girk Banastightsutyun, 139.

While many of Balassanian’s poems lack a logical structure and are abstract, it is not difficult for a reader familiar with poetry to find some form of meaning in them. In this poem, drawing on her visual artistic medium, Balassanian uses light and dark and colors to take the reader on a journey of crossing borders—this time the borders of consciousness. Typically, darkness is symbolic of the mysterious, the unknown, death; while light is equated with creation, life, and enlightenment. Fluctuating between these colors and moving back and forth between the two demonstrates how Balassanian views death and life, the unknown and enlightenment, the mysterious and creation as complementary of one another rather than standing as polar opposites. It seems that the fluidity of movement between the two is an essential element in the speaker’s word (poetry) to move beyond the borders and reach a global audience. And when that happens, in a harmonious way, the colors become more highlighted and the words less emphasized. It is important to note that the movement from darkness to light is usually accompanied with anxieties and precautions; it is a difficult process to journey into enlightenment. But this journey is just that—a journey; there is no final destination since the movement back to darkness is inevitable. Hence, what is significant is not the dualistic view of the darkness versus light but the combination of all the colors in between. Those are the colors which allow Balassanian’s speaker to move from light to light; that is, across borders. The poem which begins with the polarity of light and dark gradually moves towards a pluralistic view of all colors lending themselves to a mobility beyond borders, breaking walls, opening gates. In this way, with the imagery of colors and words, not only do Balassanian the painter and Balassanian the poet coexist, but also polar opposites merge into plurality.

After the Islamic Revolution and her immigration to the US, Balassanian reinvented herself through her art and poetry. Re-reading and re-envisioning her Iranian Armenian culture, she rewrote her story. Much of the work in her second book focuses on the trauma and pain of leaving a homeland (the past) which no longer exists, which is unattainable. However, in this poetry, Balassanian resists the suffering and victimhood from this exodus all the while acknowledging its existence. Suffering has historically been integral iconography; however, most often only suffering that has been a consequence of divine or human wrath has been considered worthy of art.13Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Picador, 2003), 40-1. While this might be true, Balassanian’s poetry is devoid of such wrath; instead, her poems allow the reader to commiserate with the speaker’s pain, which all the while they do not romanticize or normalize. Balassanian’s poetry is more than a reminder of pain and suffering; it invokes resistance and survival.

Returning home without a suitcase, Organizing the empty room, Forgetting the memories of a lifetime, Ignoring life’s barrenness, Feeling the empty room’s white light And crying silently.

Undressing in the empty bed, Not putting flowers in the vase, Not feeling the pain to the bones.

Organizing the furniture silently.14Balassanian, Yirku Girk Banastightsutyun, 163.

Balassanian’s poems bear witness to the calamitous and the reprehensible—what has befallen her country (Iran and Armenia), which has led to mass migrations. Nevertheless, her poetry refuses to surrender to such calamity; the speaker in this poem returns to an empty home devoid of past memories and resistant to pain, yet can still see the “room’s white light.” Balassanian’s poetry generates, documents, and creates remarkable exaggerations about the speakers, or poet’s, pain. The exaggeration allows for the suffering and the trauma to move beyond the personal, to loom larger, to become global, collective. The sorrowful tone of the poem invites the reader to ponder on the vastness and irrevocability of the “supposed” misfortune. With a trauma on this scale, only abstract poetry—one without the expected logic, one pregnant with visuals and imagery—can make the reader “feel” insofar as it brings the painful closer to reality by making it candidly visible.

Desert Eternal Desert They are taking On their shoulders The image of a worn face. It is wilderness Alarmingly Hot In man’s soul The universe is thickening Pouring On the image …15Balassanian, Yirku Girk Banastightsutyun, 183.

While poetry might allow the reader to watch, to care, to feel the pain from a distance, it does lend itself to moments of contemplation in order to deepen our sense of reality. To convey the suffering and pain of the modern man (the immigrant), in this poem, Balassanian resorts to an iconic symbol in classical Persian poetry, that of the desert. For instance, Majnun, the lover, runs to the desert where he finds the divine beloved. Deserts can have spiritual implications as they are the open spaces where awakening happens. Deserts as arid and desolate spaces are reminiscent of openness, borderlessness, with no protection. On the one hand, deserts invoke a sense of danger, hostility, fear, loss, emptiness, and threat as they cannot shelter us. On the other hand, located on the margins, outside of city centers, deserts are open, borderless, and liberating. Deserts can also be the locus of exile and absence of homeland with feelings of alienation and isolation.

In all her works, Balassanian asks the readers to observe, to witness, to remember without specifically referring to a certain calamity; hence, their global social justice impact. While her poetry can be read in the context of sociopolitical issues within Iran or Armenia, they are also easily applicable to global matters. Remembering, our memories, connect us to a past long gone by. Remembering is in our nature. As philosopher and political activist, Susan Sontag astutely puts it:

History gives contradictory signals about the value of remembering in the much longer span of a collective history. There is simply too much injustice in the world. And too much remembering embitters. To make peace is to forget. To reconcile, it is necessary that memory be faulty and limited.16Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 115.

To make peace, to forget, to reconcile, Balassanian creates art and writes poetry that celebrates survival as they acknowledge the pain too.

![Claudia Yaghoobi Photo 2 [CY]](https://poets.iranicaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Claudia-Yaghoobi-Photo-2-CY-150x150.jpg)