Dismantling the Poetic Father: Case Studies of Ātifah Chahārmahāliyān and Pigāh Ahmadī

Persian avant-garde poetry stands as a cultural phenomenon characterized by its dual pursuit of aesthetic revolution and defiance against prevailing sociopolitical and cultural norms. Central to understanding this movement is the recognition of its roots in the pioneering yet often overlooked works of the 1940s to the 1950s, spearheaded by Tundar Kiyā and Hūshang Irānī. Their artistic endeavors not only challenged established literary conventions but also advocated for radical transformations in poetic expression and aesthetics, aiming to pave the way for new realms of creativity. Their legacy remains a cornerstone for subsequent generations of avant-garde poets in the 1960s and the 1970s, embodying a heritage defined by relentless innovation and the unyielding quest for artistic liberation.

While Ahmad-Rizā Ahmadī’s poetry collection, Tarh (Sketch, 1341/1962) marks a significant starting point for Mawj-i naw (The new wave), its identity as an avant-garde movement solidified through periodicals such as Jung-i turfah (Novel collection, 1343/1964) and Juzva-yi Shi‘r (Poetry booklet, 1345–6/1966–7). Ismā‘īl Nūrī-‘Alā’s delineation of the evolution of Mawj-i naw reveals distinct branches, particularly Shi‘r-i dīgar (Other Poetry) and Shi‘r-i hajm (Espacementalisme, Volume Poetry), each embracing experimentalism and avant-garde sensibilities.1Īsmā‘il Nūrī ‘Alā, Suvar va asbāb dar shi‘r-i imrūz-i Irān (Tehran: Bāmdād, 1348/1969), 319. The publication of the journal Shi‘r-i dīgar in 1347/1968 signaled a departure from traditional norms, with poets like Bīzhan Ilāhī, Bahrām Ardibīlī, and Parvīz Islāmpūr leading the charge of innovative poetic forms. The essence of Other Poetry persisted through Mawj-i nāb (Pure Wave) poetry, spanning the period from pre-1358/1979 to the aftermath of the Iran–Iraq War. Despite facing skepticism amidst turbulent political climates, poets such as Manūchihr Ātashī, Sayyid ‘Alī Sālihī, Hurmuz ‘Alīpūr, and Hūshang Chālangī maintained relevance within the literary landscape.

In the late 1980s, high-modern and avant-garde Persian poetry found a prominent place in the public sphere, owing to the proliferation of periodicals dedicated to arts and literature. Journals like Ādinah, Takāpū, Gardūn, and Dunyā-yi sukhan, followed by Kārnāmah in the 1370s/1990s and early 1380s/2000s, paved the way for a new generation of poets whose work diverged significantly from the established traditions of modern Persian poetry in the 1340s/1960s and 1350s/1970s. Moreover, throughout the 1370s/1990s and 1380s/2000s, the literary community became increasingly active in translating and discussing the ideas of contemporary philosophers like Jacques Derrida, Roland Barthes, Jean François Lyotard, and Jean Baudrillard. Notably, books serving as comprehensive guides to literary theory, such as Sākhtār va ta’vīl-i matn (Structure and hermeneutics of the text) by Bābak Ahmadī and Literary Theory: An Introduction by Terry Eagleton, gained significant popularity in this period, establishing themselves as essential resources for self-study and scholarly exploration.2For a detailed analysis of this subject, see: Amīr Ahmadī Āriyān, Shu‘ār-nivīsī bar dīvār-i kāghazī: Az matn va hāshīyah-yi adabīyāt-i mu‘āsir [Wall writing on paper: From the texts and peripheries of contemporary literature] (Tehran: Chishmah, 1393/2014), 21–55. The publication of these influential theoretical works, coupled with the emergence of literary circles and workshops open to revisionary approaches toward modernist poetry, contributed to an unprecedented surge in the publication of poetry collections, theoretical books, and articles during this period. This trend peaked between the years 1376/1997 and 1384/2005, commonly referred to as dahah-yi haftād (The seventies) in Persian literary criticism. This period stood out from its predecessors due to the vibrant literary scene it fostered and the passionate discussions it engendered about concepts such as postmodernism, revolution in poetic language, syntactic deviations, and the imperative of transcending the canonical faces of modern Persian poetry such as Nīmā Yūshīj, Ahmad Shāmlū, and Mahdī Akhavān-Sālis.

This article aims to explore the metaphor of literary paternity prevalent in the 1370s/1990s and 1380s/2000s by analyzing the transformative struggle experienced by the new generation of poets during this period. It delves into what appears as anxiety by women writers in establishing themselves as authors within a literary canon that is dominated by patriarchal norms and male authors. The article further investigates the process of remembering the poetic foremother, Forough Farrokhzad, by women poets of the 1370s/1990s and 1980s/2000s, whose work offers an alternative path in poetic practice. After providing a brief overview of the main characteristics of what can be termed “Foroughic” poetry, this article delves into the career of Ātifih Chahārmahāliyān and explores how she maintains her autonomy as an avant-garde female poet while building upon the foundations of modern Persian poetry with insights drawn from Forough. Additionally, the article examines the works of another influential poet of this era, Pigāh Ahmadī, who demonstrates a significant departure from her predecessors as she seems to grapple with both the anxiety of influence and the anxiety of authorship within the male-dominated literary landscape that shaped the modernist sector of women’s poetry. Throughout the discussion, the experimental approaches of these poets in the formal aspects of their poetry, particularly the utilization of Furoughic rhythmic systems and syntactic deviations, will be scrutinized through close readings of select stanzas by each poet.

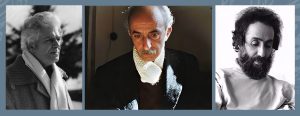

Figure 1: Frome left: Portrait of Forough Farrokhzad, Ātifah Chahārmahāliyān, and Pigāh Ahmadī

The metaphor of literary paternity in the 1370s/1990s and 1380s/2000s

A significant hallmark of poetry during the 1370s/1990s and 1980s/2000s was the concerted effort to deconstruct the metaphor of literary paternity that was deeply embedded in Persian literary history. This era witnessed a multitude of critiques directed at the modernist poetic fathers whose works had long been regarded as the unquestionable canon within Persian poetry. One can trace the origins of this approach to Rizā Barāhanī’s essay, “Chirā man dīgar shā‘ir-i Nīmā’ī nīstam” (Why I am not a Nimaic poet anymore). In this essay, Barāhanī articulates the imperative need for a critical examination of the works of modernist poetic fathers, particularly Nīmā and Shāmlū. The essay endeavors to bring to light the inherent contradictions present in the poetry and theories of Nīmā Yūshīj and arguably his most influential proponent, Ahmad Shāmlū.3Rizā Barāhanī, Khatāb bih parvānahʹhā va chirā man dīgar shā‘ir-i Nīmā’ī nīstam [Addressed to the Butterflies and why I am not a Nimaic poet anymore] (Tehran: Markaz, 1374/1995), 123–98. Barāhanī contends that these inherent contradictions could organically propel Persian poetry into a phase necessitating a “surpassing” of the poetry crafted by these influential poetic forebears: Nīmā, known for introducing a form of free verse, and Shāmlū, recognized for perfecting a variation of blank verse in Persian poetry.

He posits that an apparent contradiction emerges in Nīmā’s theories and poetry, where he alternately prioritizes either meaning or form. He contends that Nīmā views formal elements merely as tools for crafting poetry, detached from its essence. Essentially, Barāhanī suggests that Nīmā, and to some extent Shāmlū, perceive poetic form and content as entirely distinct entities despite advocating in their theoretical works for their harmonious integration in a “natural order” during poetic composition. Barāhanī articulates, “In the poetry of both great poets, Nīmā and Shāmlū, a blend of the Enlightenment era and the Romantic movement becomes evident, which are the two uber-narratives behind European modernism and global modernism. Central to this is the notion of separating the thinker from the world of the thought’s subject matter, which stems from Cartesian thought and its dualism.”4Barāhanī, Khatāb bih parvānahʹhā, 196. Additionally, Barāhanī observes that Nīmā’s Cartesian perspective, which separates the world into subject and object, serves as a framework through which he articulates his inner turmoil and challenges.5Barāhanī, Khatāb bih parvānahʹhā, 129.

After establishing these contradictions, Barāhanī seeks to articulate his own creative output to a new generation of poets. In essence, he delves into the intricate relationships between himself as a poet and his forerunners, suggesting that poets grapple profoundly with the impact of past literary figures in their creative pursuits. This argument aligns with the Bloomian theory of the anxiety of influence, where major poets confront the challenge of navigating the powerful influence of their predecessors, especially those designated as the strong precursors. Nīmā and Shāmlū, having left an indelible mark on Persian literary history, represent such influential figures. Barāhanī perceives a necessity to liberate himself from the pervasive influence of these poets, prompting him to critically reassess their theories and adopt a revisionary approach toward their works, thereby theorizing his own poetry. His “revisionary” approach signifies a dynamic process wherein poets actively interact with the Persian literary tradition, reinterpreting and reshaping the works that precede them. This transformative process emerges as integral to the creation of new and original poetry.

Barāhanī staunchly believed that the primary means of resisting the hegemony of poetic fathers over emerging poets lies in dismantling the patriarchy of syntax. Consequently, he placed significant emphasis on this concept in his theories of “zabāniyat” (language poetics), delving into unexplored aspects of Persian syntax and grammatical qualities that had been neglected by his predecessors. In expressing this idea, he articulates, “There are hidden places in the Persian language where grammar and syntax did not dare to go; even Persian poetry did not dare to venture [into those realms].”6Barāhanī, Khatāb bih parvānahʹhā, 187. These concealed linguistic spaces represent areas where new poets faced vulnerabilities, hesitating to experiment with their expressive systems due to the lack of validation from their poetic predecessors. Barāhanī’s focus on challenging established syntax and grammar becomes a strategic maneuver to liberate emerging poets from the constraints imposed by the conventions of their literary forebears.

The same notion, albeit expressed in a less theoretical manner, resonates in the words of the younger generation of poets during the 1370s/1990s and 1380s/2000s. Their mission, as expressed by influential poet Mihrdād Fallāh, was to bring the cosmic poetic fathers down to earth, aiming to make the poet accessible, as he put it, “from the sky to the street.”7Mihrdād Fallāh, “Va chinīn shud ki shā‘ir az āsimān bih khīyābān qadam guzāsht,” Farhang-i tawsi‘ah, no. 49 (May 2001): 10. This endeavor marked a revisionary movement, a deliberate effort to reshape the dynamics of the modern Persian literary canon. Bihzād Khvājāt, another influential poet of this era, criticizes the excessive focus on “Nīmā and three or four other poets,” referring to giants like Ahmad Shāmlū, Mahdī Akhavān-Sālis, Sohrab Sepehri, etc. Khvājāt argues that this fixation neglects the pressing needs of the contemporary moment, emphasizing that Nīmā’s demolition of structures in his time is not a current necessity. In other words, the contemporary poets of this era acknowledge the influence of Nīmā and other prominent modernists from earlier generations, up to the extent where they challenge the entrenched conventions of literary creation in their time. However, they reject the adherence to the “Nimaic tradition” that prevailed from the 1960s to the 1990s. Khājāt contends that Nīmā served as a path, not a destination, and emphasizes the need to move beyond merely walking in his footsteps.8Bihzād Khvājāt, Munāzi‘ah dar pīrhan: Bāzkhānī-yi shi‘r-i dahah-yi haftād [Conflict in the shirt: Rereading the poetry of the seventies] (Ahvaz: Rasish, 1381/2002), 55.

Despite this transformative struggle, the prevailing narrative still viewed the poetic evolution through the lens of a father-son conflict, with emerging poets striving to break free from canonical figures and amplify their unique voices. Yet, amid this narrative, the contributions of women poets often went unnoticed, as they embarked on a distinct trajectory to deviate from their immediate literary tradition. According to Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar:

[The male poet] conceals his revolutionary energies only so that he may more powerfully reveal them, and swerves or rebels so that he may triumph by founding a new order, since his struggle against his precursor is a “battle of strong equals.” For the woman writer, however, concealment is not a military gesture but a strategy born of fear and dis-iase. Similarly, a literary “swerve” is not a motion by which the writer prepares for a victorious accession to power but a necessary evasion.9Gilbert Sandra M and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 74.

For these women poets, deviating from patriarchal literary standards was not sufficient; they embarked on a quest to find a poetic foremother with whom they could engage in a meaningful dialogue. This nuanced approach acknowledged the need for a more inclusive and diverse literary lineage, acknowledging the significance of women’s voices in shaping the evolving landscape of Persian poetry. In essence, the Bloomian model of literary historiography, evident in the expressions of Barāhanī and the younger generation of poets during that era, proves to be deeply patriarchal. These poets not only portray their role in literary history as sons engaged in a struggle against their fathers but also metaphorically frame their poetic journey as a means of grounding the cosmic and god/father figure predecessors in earthly realms. Consequently, the women poets faced a twofold challenge: redefining the struggle against the poetic father as a revisionary approach rather than an Oedipal complex and seeking a foremother whose work could serve as an alternative path in poetic expression. The prevailing narrative, steeped in patriarchal undertones, underscored the need for a shift in perspective.

Gilbert and Gubar assert that implicit in the metaphor of literary paternity is the notion that each man, upon reaching the creative maturity or “puberty” of his creative gift, possesses the capacity, and perhaps even the obligation, to engage in a discourse with other men by creating alternative narratives. This ability allows men to challenge existing fictions and generate their own. However, the metaphor also reveals a stark gender disparity in patriarchal societies. Women, lacking the symbolic tools equivalent to the pen/penis that enable men to engage in this discourse, have historically been marginalized to the status of mere properties. They are depicted as characters and images confined within male-authored texts, a condition imposed on them solely by male expectations and designs.10Gilbert and Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic, 12.

Remembering the Poetic Mother

Gilbert and Gubar introduced the term “the Anxiety of Authorship” in response to what they perceived as a sexist and male-dominant framework embodied by Bloom’s “Anxiety of Influence.” Bloom’s theory posits that poets grapple with anxiety concerning their literary predecessors, fearing the stifling of their creative voice through excessive influence. This anxiety emerges from the necessity to break free from earlier writers to establish a distinctive voice. In contrast, Gilbert and Gubar assert that women writers experience anxiety rooted in patriarchal norms and a literary canon dominated by male authors, coining the term “anxiety of authorship.” For women, this anxiety is intertwined with issues of identity, voice, and the struggle to assert perspectives within a historically male-centric literary landscape. Their theory offers an antithetical revision of Bloom’s Anxiety of Influence, providing insight into the dynamics of female literary responses to male assertion and coercion.11Gilbert and Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic, xviii. Gilbert and Gubar’s framework focuses on how women writers overcome the anxiety of authorship, transcending patriarchal prescriptions, and reclaiming the influence of lost foremothers. In essence, this theory serves as a counterpoint, offering a nuanced understanding of the complexities inherent in female literary expression within a traditionally male-dominated literary tradition.12Gilbert and Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic, 59.

It is a prevailing opinion that the Persian-language women poets who paved the way in the 1990s and 2000s were inevitably seeking inspiration from none other than Forough Farrokhzad. In one of the influential theoretical works from the 1370s/1990s, Guzārahʹhā-yi munfarid (Separate Articles, 2001), ‘Alī Bābāchāhī examines how these poets, particularly those in the 1980s and 1990s, were inspired by Forough’s conversational style and her exploration of anti-patriarchal themes. Bābāchāhī looks closely at the works of moderate modernists like Nidā Abkārī, Nāzanīn Nizām-Shahīdī, Gītī Khushdil, and Zhīlā Mosā‘id to illustrate this influence.13‘Alī Bābāchāhī, Guzārahʹhā-yi munfarid [Single statements] (Tehran: Sipantā, 1374/1995), 2: 816–70. However, he struggles to understand the efforts of other women poets, such as Girānāz Mūsavī and Ruzā Jamālī, who sought to challenge literary patriarchy through radical experimentation with form. The works of these two poets that Bābāchāhī has studied align with the two we are exploring in this article, and later in the discussion, I will demonstrate how they confront and destabilize literary patriarchy by engaging in similar radical experimentation with language and form.

One may argue that Forough’s poetry not only liberated her poems from patriarchal themes and tones but also broke away from the aesthetic norms and formal features advocated by the father of Modern Persian Poetry, Nīmā Yūshīj. Shams Langrūdī asserts that the second transformative wave in the thousand-yiar history of poetry emerged with Forough’s pioneering contributions, following in the footsteps of Nīmā.14Shams Langrūdī, Tārīkh-i tahlīlī-yi shi‘ir-i naw (Tehran: Markaz, 1387/2008), 3:108. Forough acknowledged that overhauling the prosodic system of Persian poetry, deemed the most sacrosanct aspect of poetic tradition, equated to forging a new paradigm. However, she opted not to attribute her experiments in poetic forms, which will be explored further in this article, to her male predecessors, notably Nīmā.

I looked at the world around me, with the objects around me and the main lines of this world. I discovered it, and when I wanted to express it, I realized I needed words, fresh words related to that world. If I were to be afraid, I would die. But I was not afraid. I brought in the words. What does it matter that these words have not yet become poetic? They have life. We make them poetic. The words that entered [poetry], as a result, needed changes and modifications in the rhythm. If this need did not naturally arise, Nīmā’s influence could not do anything. He was my guide, but I was my own creator. I have always relied on my own experiences.15Furūgh Farrukhzād, Harfʹhā-yī bā Furūgh Farrukhzād [Conversations with Furūgh Farrukhzād ] (Berlin: Navīd, 1989), 28.

Mahmūd Nīkbakht contends that Forough Farrokhzad’s contributions to poetic forms, particularly evident in her last two poetry collections, Tavalludī dīgar (Another birth, 1342/1963) and Īmān biyāvarīm bih āghāz-i fasl-i sard (Let us believe in the beginning of the cold season, 1353/1974), not only surpassed Nīmā Yūshīj’s endeavors in transforming poetic forms, such as the creation of a new rhythmic system and striving to make the poetic language more akin to the nature of spoken language, but also better captured the essence of the modern era by aligning language and rhythm with contemporary sensibilities.16Mahmūd Nīkbakht, Az gumshudigī tā rahā’ī [From loss to liberation] (Isfahan: Mash‘al, 1372/1993), 39. Nīkbakht suggests that while Akhavān-Sālis utilized Nīmā’s prosody as a mere decorative element, and Shāmlū, despite departing from traditional prosody, retained an elitist tone through archaic language, it was Forough who revolutionized modern Persian poetry.17Nīkbakht, Az gumshudigī, 39. He asserts that in the long poem “Let Us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season,” Forough charted a new course by substituting the archaic and elitist tones enforced by the forefathers of modern poetry with a vernacular language and rhythmic system. As Barāhanī highlights, this new direction is just as significant as Nīmā’s movement, as it has established a “new mindset and language” for Persian-speaking women. However, the innovation of Forough’s poetry extends beyond its feminine qualities to its broader emancipatory purpose, both in literature and in society.18Nāsir Harīrī, ed. Hunar va adabiyāt-i imrūz: Guft-u-shunūd-i Ahmad Shāmlū va Duktur Rizā Barāhanī [Today’s art and literature: A conversation between Ahmad Shāmlū and Dr. Rizā Barāhanī] (Babol: Kitābsarā-yi Bābol, 1365/1986), 125.

While Nīmā advocated for new poets to align the language and tone of their poetry with the natural cadence of everyday speech, it was Forough who decisively departed from the elitist tone prevalent in modern Persian poetry. According to Sīrūs Shamīsā, Forough’s poetic language in the aforementioned poetry books is distinguished by its musicality, gentleness, sincerity, and fluidity, rendering it perhaps the closest approximation to the natural rhythm of everyday conversation. Shamīsā notes that Forough’s language derives its musical quality from dialogue and narrative rather than strict adherence to prosody.19Sirūs Shamīsā, Nigāhī be Furūgh [Reviewing Furūgh] (Tehran: Morvārīd, 1997), 96. Additionally, Forough emphasizes the value of sincere expression in poetry over elitist linguistic conventions.20Farrukhzād, Harfʹhā-yī bā Furūgh Farrukhzād, 21.

Regarding the rhythmic system attributed to Forough, as elucidated by Mohammad-Rizā Shafī‘ī Kadkanī, the meters employed in Forough’s poetry, particularly in the later stages of her poetic career, often commence with a commitment to qualitative equality in approximately eighty percent of cases within the initial foot. However, as the verse progresses beyond the first hemistich, subsequent feet may diverge qualitatively into different meters or extensively incorporate metrical variations.21Muhammad-Rizā Shafī‘ī Kadkanī, Advār-i shi‘r-i Fārsī: Az mashrūtiyat tā suqūt-i saltanat [Periods of Persian poetry: From the Constitution to the fall of the monarchy] (Tehran: Sokhan, 1380/2001), 76–77. Simin Behbahani explains that Forough’s poetry not only surpasses the expected qualitative equality of prosodic poems but also disrupts the rhythm and order of prosodic feet. In simpler terms, Forough disregards the beat to accommodate the words she wants to use in her poem.22Sīmīn Bihbahānī, Yād-i ba‘zī nafarāt [The memory of some people] (Tehran: Alborz, 1378/1999). 343–44. As she has asserted, “If a word such as infijār (explosion) does not fit into the meter and creates a disruption in rhythm, well, this disruption should be considered a knot in the thread of the meter.”23Farrukhzād, Harfʹhā-yī bā Furūgh Farrukhzād, 33.

In the poems analyzed in this article, I will explore the Foroughic poetic forms that expand upon and depart from the reinterpretation of Nimaic prosodic systems towards approximating prosodic meters. I will also observe how the rhythm is disrupted by breaking the rules of syntax and prioritizing experimentation with the fundamentals of language. These poems take a different approach to the concept of poetic language and offer a revisionary perspective on the relativity of Foroughic poetry. To better understand this revisionary approach, I will analyze these works within the context of the 1990s and 2000s Persian poetry. Poets like Ātifah Chahārmahāliyān and Pigāh Ahmadī, drawing from their experiences with their poetic foremother, navigate both the anxiety of authorship and the anxiety of influence as they strive to find their voice and autonomy as avant-garde poets within the male-dominated realm of modern Persian poetry.

Figure 2: Frome left: Ahmad Shāmlū, Nīmā Yūshīj, and Sohrab Sepehri

Ātifah Chahārmahāliyān: Autonomy and Poetic Innovation

Although she found her voice among the plethora of poets in the late 1370s/1990s and early 1980s/2000s, Ātifah Chahārmahāliyān stands out as a remarkable and influential woman poet from this dynamic period. Born in Khuzestan in 1360/1981, her literary journey began with the publication of her first poetry collection, Ma‘shūq-i kāghazī (Paper lover, 1378/1999). This was followed by another collection titled Dāram bā rushd-i shānih′hā-yi miyyit rāh mīravam (I am walking along the growth of the corpse’s shoulders, 1381/2002). Subsequently, she released Baghalam kun Shiblī (Hold me, Shibli, 1384/2005), Kitābī kih nimīkhvāstam (The book I did not want, 1393/2014), and Zartushtak-i Sīstānī: Sīzdah sālah: Zādah va marg (Little Sistani Zoroaster, Thirteen years old: Birth and death, 1402/2023). In addition to her literary contributions, Chahārmahāliyān is recognized for her activism in children’s rights. She served as a board member of the Writers’ Association of Iran until her arrest and imprisonment for her involvement in the “Women, Life, Freedom” uprising.

Engaged in a continuous dialogue with her poetic foremother, Forough Farrokhzad, Chahārmahāliyān’s literary journey unfolds as a compelling counterpoint to the prevailing father-son conflicts of the era. In a landscape dominated by male-centric narratives, Chahārmahāliyān’s works, particularly in collections like I am walking along… and Hold me, Shiblī serve as poignant testaments to her deliberate act of recovering and remembering Forough. Chahārmahāliyān’s poetic expressions extend beyond mere references. She actively addresses Forough in several instances within her poetry, establishing a profound connection with her foremother. However, her engagement goes beyond homage, as she embarks on a journey to pursue and perpetuate Forough’s experimental spirit with poetic language and forms.

Indeed, Chahārmahāliyān’s poetic dialogue with Forough is overtly evident in the title of her poem “Darīghāh-i Forough ke ‘raft’ fi‘l-i ākhar-i ū dar dahān-i avval-i man būd” [A requiem for Forough, whose last verb, “went,” was in my first mouth] from the collection I am walking along… . This title serves as a clear declaration, suggesting that the poet perceives her own poetry as a seamless continuation of Forough’s legacy. The poignant choice of the title not only underscores a thematic connection but also symbolizes the passing of the last experiments of the foremother, meaning her works in Another birth and Let us believe…, into the initial utterances of the young poet.

This apparent influence, however, should not be misconstrued as a mere submission to a stronger predecessor. Instead, it signifies a deliberate intertextual dialogue that Chahārmahāliyān aims to establish with Forough’s body of work. The presence of Forough’s last verb in the young poet’s mouth becomes a symbolic representation of the ongoing conversation between generations, where influence is not a one-way street but a dynamic interplay of voices across time. Chahārmahāliyān’s engagement with Forough’s legacy reflects a conscious effort to weave her narrative into the rich fabric of Persian poetry while honoring and building upon the contributions of her poetic foremother.

با چشمها ترسیده نگاهم نکن میّت

من

با بیضلعی تو هستم بر آسفالت

که در ظهیرالدوله

انگشت فروغ درخت شده بود

به مادرم میگویم: سکته بهتر از این نمیشود

دارم

با رشد شانههای میّت راه میروم

With frightened eyes, don’t look at me, corpse

I am

With your sidelessness on the asphalt

That in Zahīr al-Dawlah

Forough’s finger had grown into a tree

I tell my mother: There couldn’t have been a better stroke

I am

Walking along the growth of the corpse’s shoulders24Ātifah Chahārmahāliyān, Dāram bā rushd-i shāniʹhā-yi miyyit rāh mīravam (Tehran: Nigāh-i Sabz, 1390/2001), 10.

Chahārmahāliyān actively invokes her poetic foremother, seeking to incorporate Forough’s distinctive perspective in the very creation of her own poetry. This intentional act of addressing Forough serves as a summoning, a deliberate invocation where Chahārmahāliyān calls upon the essence and point of view of her foremother. In doing so, she endeavors to infuse her own poetic expression with the unique lens and insights that Forough brought to the literary landscape:

نه!

از سفید بکشیدش بیرون

و دیگر نقطهچین نشود هی

پاککنات را به من برسان فروغ!

میخواهم بیمارستان گلستان پاک شود از آدم

و کاشیها و کافور

از دندانش ریخت روی پنبه

روی سرُم

No!

Pull it out from the white

And don’t let it be dotted anymore

Bring your eraser to me, Forough!

I want the Gulistān Hospital to be erased of people

Tiles and camphor

Poured from his tooth onto the cotton

Onto the IV fluids25Chahārmahāliyān, Dāram, 55.

کی بودنم کجاست وقتی استخوانهای کتفم تیر میکشند

و دستی که تعارف صندلی برهنهام کرد

آسمان لعنتی گم شو آسمان آن مرد

در باران آمد

و زیبایی سگ

لای گوشتهایم پارس میکند

تو

اما تو

هی فروغ فرخزاد

پشت پلکهایت حالا چه شکلیند؟

Where is my “who am I” when my shoulder blades are sore

And the hand which offered me the stripped chair

Damn sky, get lost!

The sky of that man came in the rain

And the beauty of the dog

Barks in the shreds of my flesh

You

But you

Hey, Forough Farrokhzad

What does it look like behind your eyelids now?26Ātifah Chahārmahāliyān, Baghalam kun, Shiblī (Kerman: Āftāb-i Kirmān, 1384/2005), 14.

Borrowing Forough’s eraser symbolizes the act of bringing Forough into the creative process. Chahārmahāliyān tries to establish a profound intertextual collaboration, tapping into the reservoir of Forough’s experiences, emotions, and artistic sensibilities through her eyes “behind her eyelids.” This act transcends a simple acknowledgment of influence; it represents a dynamic and intentional incorporation of Forough’s poetic voice into the fabric of Chahārmahāliyān’s own work. In this way, Chahārmahāliyān tries to echo Forough’s perspective that resonates within the contemporary context, enriching and shaping the evolving narrative of Persian poetry.

In addition to the pervasive influence of Forough as a poetic foremother in Chahārmahāliyān’s works, her poetry also vividly articulates a confrontational relationship with a paternal figure. This “father” figure emerges as a looming presence, serving as both a source of threat and suppression within the thematic landscape of Chahārmahāliyān’s verses. The use of the term “father” suggests a complex dynamic, one that involves authority, control, and, at times, a stifling force that seeks to impose constraints.

این پرانتز برای کمربندت پدر ( )

و با اجازه روبروی شما روبروی شما نیست.

بعد

جنازه از ارتفاع بیفتد و مرگ

بوسیدنت را به آن جهان ببرد.

These parentheses are for your belt, father ( )

And with the permission of your front, it’s not in front of you.

Then

The corpse would fall from a great height

And death would take your kissing to the other world.27Chahārmahāliyān, Baghalam kun, 9.

تو از تجاوز ترسی به آخرم از عمد

تو از شرایط مشغول مبهمی از بعد

اصلاً گور چشمهایت هم کردم

میدانم دوباره آخر این شعر

پدرم مرا کتک میزند.

You are from the fear that intrudes upon my end, knowingly,

From aftermath-ly murky realms, you emerge, a post-occupancy.

Screw your eyes, actually

I know at the end of this poem too

My father is beating me up again.28Chahārmahāliyān, Baghalam kun, 22

پدر تلقی شد به یک انضمام فاشیستی

زنها صلوات کشیدند و این بچه

در انفرادی همهی وقت مرا گرفته

به دیوار کلمههای کمرنگ

میکشد.

Father was perceived as a fascist integration

Women shouted prayers and this child

Has taken all of my time in solitary confinement

Drawing faint words on the wall.29Ātifah Chahārmahāliyān, Zartushtak-i Sīstānī: Sīzdah sāla; Zādah va marg (Oslo: Āftāb, 1402/2023), 135.

The confrontational stance towards the paternal figure introduces a layer of tension and resistance in Chahārmahāliyān’s poetry. The paternal presence becomes a symbolic representation of societal norms, authority structures, or perhaps a specific individual against whom the poet asserts her voice and individuality. The juxtaposition of the nurturing and influential maternal presence with the confrontational paternal figure creates a nuanced exploration of power dynamics, gender roles, and the poet’s quest for autonomy within the complex tapestry of her poetic expression. Chahārmahāliyān’s poetry thus unfolds as a multifaceted narrative, intertwining personal and societal struggles, shaped by the influences of both a nurturing foremother and a challenging paternal force.

خطکش که رفت بالا

کف دستهایم را گرفتم زیر

جنین با مه نگاه کرد به توت فرنگیها

معلم زیر کفن

پدر توی معلم

من؟

آ…ی…ی…ی.

زیر سفید

روی کاشی گفته بودم انگار…

بزنم، بزن، بزن مرا.

When the ruler was raised

I held the palms of my hands underneath

The fetus looked in fog at the strawberries

The teacher under the shroud

The father within the teacher

And I?

Arrgghhh…

Underneath the white

On the tiles, I seem to have said

Hit me, hit, hit me.30Chahārmahāliyān, Dāram, 49.

One could argue that this “father” figure serves as a metaphor for literary patriarchy within her poetry. In many instances, the father’s presence extends beyond a mere portrayal of a specific individual in the real world, transcending into the archetype of a progenitor, a procreator, and an aesthetic patriarch. As elucidated by Gilbert and Gubar, the father/poetic father’s pen symbolizes a generative power akin to his penis. Furthermore, this power, inherent in both the pen and the penis, extends beyond mere creation; it encompasses the authority to lay claim to a posterity that the father himself has generated. Thus, the father figure in Chahārmahāliyān’s poetry embodies not only patriarchal dominance but also the assertion of authority over the literary lineage and the subsequent generations of writers.31Gilbert and Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic, 20.

This leads us to a pivotal characteristic of Chahārmahāliyān’s poetry: its resistance to categorization within a specific poetic style of her time. While her work bears clear influences from movements such as Shi‘r-i dīgar (Other Poetry) and Shi‘r-i hajm (Espacementale Poetry) in the 1340s/1960s, as well as Mawj-i nāb in the 1360s/1980s, she refuses to conform her poetry to any singular movement. It appears that she harbors a fear of relinquishing her autonomy as a creator, wary that aligning her work with patriarchal literary categorizations would grant precedence to the works of her poetic fathers, both preceding and extending beyond her. In essence, the presence of the father figure in her poems symbolizes fierce power struggles in which Chahārmahāliyān engages in her quest for self-creation. Thus, her poetry becomes not only a journey of remembering her poetic foremother but also a relentless struggle with the “anxiety of influence”.

In terms of poetic forms, Chahārmahāliyān’s poetry, particularly during the 2000s, engages in a dialogue with Foroughic forms. As previously mentioned, Forough’s poetry is characterized by its liberation from the constraints of Nimaic prosody, opting instead for rhythmic patterns that approximate natural speech rhythms. Forough herself describes this rhythmic system as “a thread connecting words to each other, without being seen, just holding them together.”32Farrukhzād, Harfʹhā-yī bā Furūgh Farrukhzād, 33. Similarly, Chahārmahāliyān endeavors to experiment with this style, seeking to free her poetry from the confines of Nimaic prosody while distancing herself from the archaic language employed by poets such as Ahmad Shāmlū and Mahdī Akhavān-Sālis. By embracing Forough’s approach to poetic forms, Chahārmahāliyān aims to imbue her poetry with a sense of fluidity and spontaneity, allowing the words to flow naturally and unencumbered by rigid prosodic structures.

سرد من لای پنجره توریست

تهی از چند تای تو اما چقدر؟

دستت را بگیرم میان پیراهنم لخت

_ رهایت کنم؟

چقدر

بروم روی شوفاژهای غمگین پهنت کنم

My cold is against the window screen

Empty from a few of you, but how much?

And let you out naked amidst my dress?

How much

Should I go and hang you on the sad radiators33Chahārmahāliyān, Baghalam kun, 11.

As evident from the previous analysis, the poet endeavors to create a harmonious rhythmic system in her poetry by integrating the disruptions introduced by everyday words like “panjarah-yi tūrī” (window netting) and “shufāzh” (radiator). This approach aligns with Forough’s perspective, as she notably expressed that when a word does not seamlessly fit into the established rhythm, in this case an approximation of fā‘ilātun mafā‘ilun fa‘alun (-ᴗ–/ᴗ- ᴗ-/–) or khafīf musaddas makhbūn, and instead disrupts the flow, the poet should strive to construct a rhythm derived from these very disruptions. Forough’s insight underscores a deliberate and innovative technique employed by poets, wherein they do not shy away from incorporating words that may initially seem discordant within the established rhythmic structure. Rather than avoiding such disruptions, the poet embraces them as opportunities to craft a new rhythm, injecting vitality and authenticity into the poetic composition. This approach reflects a keen awareness of the expressive potential inherent in the ordinary and the disruptive, allowing for a dynamic interplay between linguistic irregularities and the rhythmic cadence of the poetry.

Another important characteristic of Chahārmahāliyān’s poetry is her use of “ecstatic utterances” as one of the main ways of poetic expression. Ecstatic utterances in poetry refer to expressions of intense emotion, often marked by heightened language, repetition, or rhythm, conveying an overwhelming sense of spiritual, emotional, or creative transcendence. Shafī‘ī Kadkanī, considers the use of “ecstatic language” in modern poetry as detrimental to the rationalist nature of Persian poetry inherited from the classical canonical works, particularly those created before the second half of the twelfth century. He labels these poems as “shi‘r-i jadvali” (multiplication table poetry) and defines them as a form of verse in which the author metaphorically and figuratively attains coherence by the random arrangement and combination of words, akin to the structure of a multiplication table. He states that this process occurs without any predetermined thoughts, feelings, or reflections about each element. The beauty and poetic essence of these “multiplication table” images often stem from the surprising occurrences that arise within these arrangements, creating striking poetic representations.34Muhammad-Rizā Shafī‘ī Kadkanī, “Shi‘r-i jadvalī: Āsīb-shināsī-yi nasl-i Khirad-gurīz” Iranʹshināsī 10, no. 39 (Fall 1377/1998): 479–90.

For Chahārmahāliyān, ecstatic utterances find their roots in the dialogue between her poetry and the tradition of shath, explained below, in Sufi literature. It can be observed that all the poetic movements associated with Chahārmahāliyān’s poetry—such as Other poetry, Espacementale poetry, and Pure wave—engage in a discourse with the aesthetic aspects of mysticism and Sufi literature. Bījan Ilāhī, a prominent figure within the Other Poetry poetic group, provides commentary on the interplay between mysticism and Espacementale Poetry, reflecting on the manifesto of this poetic movement. He suggests that embracing a convention while simultaneously rejecting all conventions embodies a mystical approach. Ilāhī emphasizes that the essence of Espacementale Poetry is imbued with a mystical spirit, attributing the movement itself to a form of mysticism within poetry. He asserts, “Our movement is mysticism in poetry. We mysticize in poetry.”35Yad-Allāh Rawyā’ī, Halāk-i ‘aql bih vaqt-i andīshīdan (Tehran: Nigāh, 1393/2012), 44. In other words, the avant-garde poetic trends reflected in Chahārmahāliyān’s poetry exhibit a clear connection with the introduction of mystic elements as fundamental aspects of their poetic experiments. In some cases, these trends even theorize their poetic practice based on these mystical elements.36To read about the influence of mystical literature on modern literary theories of Shi‘r-i dīgar movement, please see: Rebecca Ruth Gould and Kayvan Tahmasebian, “Translation as Alienation: Sufi Hermeneutics and Literary Modernism in Bijan Elahi’s Translations” Modernism/modernity 5, no. 4 (July 2019). https://doi.org/10.26597/mod.0175 Chahārmahāliyān herself underscores this connection by naming her third and most celebrated poetry collection Hold me, Shiblī, invoking the name of Abū Bakr al-Shiblī (d. AH 334/ 946), a renowned Sufi of Iranian descent. This deliberate choice serves as a testament to her continuous dialogue with Sufi literature throughout the book, emphasizing her engagement with the spiritual and mystical themes explored by Sufi thinkers and poets.

In addition to the thematic influences from Sufi literature, one may argue that the main formal aspect of these poems is the role of ecstatic utterances or shath in the formation of imagery. Carl W. Ernst defines shath as a technical term in Sufism meaning ecstatic expression, “commonly used for mystical sayings that are frequently outrageous in character. The root s̲h̲-ṭ-ḥ has the literal meaning of movement, shaking, or agitation, and carries the sense of overflowing or outpouring caused by agitation.” 37Carl W. Ernst, “Shath,” in Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd ed., vol. 9 (Leiden: Brill,1997), 361–62. In the following stanza, imagery is crafted through an arbitrary convergence of senses, blending elements like smell and color, while intricately weaving paradoxical concepts and objects such as desert, dampness, departure, and dead-inds:

تا از چهرهای بنفش

رنگها ماورای خود را عبور دهند

چشمهای تو بوی جلبک بود و عشق

خیسی بنفش

بیابانی بنفش

تا نرفتن من هست با پاهایم در رنگ

از کوچ میگریزد کوچه در تابلوی بنبست.

Until from a purple face

Colors pass their transcendence

Your eyes were the smell of algae and love

Purple dampness

A purple desert

As long as my not going exists, with my feet in paint

The alley escapes from departure in the dead-ind sign.38Chahārmahāliyān, Dāram, 71

Despite the mechanical understanding of Shafī‘ī from the process of creation of such poetic expressions, ecstatic utterances in this stanza have been a way of adding multiple layers and volume to an image. Simin Behbahani, writing about the process of the creation of an image, explains the notion of layers and volume in poetic images: “my use of the term “volume” doesn’t actually refer to the geometric concept. I mean lines of imagination that intersect with each other, emerging in the mind’s eye.”39Yad-Allāh Rawyā’ī, ‘Ibārat az chīst:Az sakū-yi surkh 2 (Tehran: Āhang-i Dīgar, 1386/2007), 186. Theorizing imagery in Espacementale Poetry, Yad-Allāh Rawyā’ī explains that despite the conventional way of creating images through metaphors and similes that are composed of a vehicle and tenor, this kind of poetry adds a third layer to the image, which is the “movement.”40Rawyā’ī, ‘Ibārat az chīst, 384–85. For instance, in the previous stanza by Chahārmahāliyān, instead of saying your eyes are like green algae when they are wet and are like the dessert when they are dry, she tries to change the two-dimensional metaphors into three-dimensional images by adding the layers such as scent and color as well as giving fluidity to the components of parallel images.

Pigāh Ahmadī: Anxiety and “Languageality”

Pigāh Ahmadī, born in 1353/1974, emerged as a notable poet in the 1370s/1990s, renowned for exploring ecstatic utterances within her poetry. She has published five poetry collections: Rū-yi sol-i pāyānī (On the ending sol, 1378/1999), Kādens (Cadence, 1380/2001), Īn rūzʹhāyam galūst (These days of mine are throat, 1383/2004), Sardam nabūd (I was not cold, 1389/2010), and Shiddat (Intensity, 2017). She has also translated a collection of selected poems by Sylvia Plath titled Āvāz-i āshiqānah-yi dukhtar-i divānah (The love song of the mad girl, 1379/2000) and Sad u yik hayk: Az guzashtah tā Imrūz (Hundred and one haikus: From the past to the present, 1386/2007). Additionally, she compiled an anthology of Iranian women’s poetry titled Shi‘r-i zan az āghāz tā imrūz (Women’s poetry from the beginning to today, 1384/2005).

Similar to Chahārmahāliyān, the ecstatic utterances and references to mysticism in Ahmadī’s poetry serve as a means to explore new realms within the Persian poetic language. Barāhanī, in his controversial article, translated by Barāhanī himself as “The Theory of Languageality,” seeks to link this type of poetic experimentation to the foundation of Iranian mystical heritage and advocates for a reevaluation of ‘irfān or Iranian mysticism from the perspective of modern poetry. He explains that this mystical approach to language occurs when poets, without directly referencing mystical elements, explore the potentials of the Persian language through experimentation with syntax, wording, and sound.41Rizā Barāhanī, “Nazariyah-yi zabāniyat dar shi‘r,” Kārʹnāmah 46 and 47 (Āzar- Day 1383/December-January 2004–5):15.

Although Ahmadī, like many other poets of her generation, initially had an antagonistic approach towards Barāhanī’s theories in the 1990s, particularly his theory of “languageality.” However, her later and most important works are significantly influenced by the theoretical discussions surrounding this topic, particularly when it comes to her experiments with syntax. Barāhanī discusses the poetry of the new generation, which emphasizes “not only the language but also the languageality of the language.” This refers to poets whose poetry aims to transcend mere wordplay and unlock the potential of language itself. He argues that this type of poetry suspends interpretation, returning language to its fundamental elements of formation and structure, recognizing that sentences devoid of conventional meaning are still essential to the essence of language. Barāhanī suggests that there exists a realm in language where it becomes free from meaning to become beautiful”.42Barāhanī, “Nazariyah-yi zabāniyat ,” 14. In an interview with Rizā Chāychī, another prominent poet of the 1990s, Ahmadī says:

I believe that Barāhanī, with his intelligence, embarked on a skillful manipulation of poetry that resulted in plurality. His trend-setting led to the training of a group of poets who often became entangled in intellectualism and abstract thoughts, creating an illusion of poetic insight, which claimed not to want to reduce the ascendant power of language to the description of existing reality. Although sensory sparks of creativity can be felt in some of these poems, naturally, this is not all poetry should be.43Rizā Chāychī, Dāmī barā-yi sayd-i pārih abr (Tehran: Ārvīj, 1383/2004), 66.

Indeed, one can interpret Ahmadī’s antithetical approach to The Theory of Languageality as stemming from her anxiety about being influenced by her poetic father. To assess the impact of this theory on literature, Bloom has outlined six “revisionary ratios,” some of which draw on Freud’s defense mechanisms. These ratios illustrate the developmental stages of anxiety of influence concerning how a poet or author misinterprets and distorts the work of a literary precursor when composing a literary text. In Ahmadī’s case, her approach can be analyzed using the second revisionary ratio, Tessera, which Bloom defines as “completion and antithesis.” This entails elaborating on a precursor’s work while maintaining their terms and ideas but imbuing them with a different meaning, suggesting that the predecessor did not fully develop the argument in the first place.

Ahmadī also maintains a theoretical distance from her poetic foremother, Forough. In her most notable work, the long poem “Tahshīyah bar dīvār khānigī” (Reflections on the home wall), published in the book These days of mine are throat, she engages in a dialogue with Foroughic forms and rhythmic systems. However, the language of this poem does not adhere to the simplicity suggested by Forough; instead, it shows inclinations towards the languageality proposed by Barāhanī.

نسلی در افسردگی من جاریست

از شارب پدر گذشته و نُه ماهیست

از زن که نردههای سفارت را میگرفت و قرن را جلو میبرد

درنمیآید این شعار

A generation flows in my melancholy,

Beyond the mustache of the father, and it’s been nine months.

The woman who used to grab the embassy’s railings and lead the century forward,

Would not chant this slogan.44Pigāh Ahmadī, Īn rūzʹhāyam galūst (Tehran, Sālis, 1383/2004), 10–11.

The first three lines of this stanza begin with an approximation of the prosodic foot mustaf‘ilun (–ᴗ-). These lines feature a qualitatively equal initial feet, but as the line progresses, the remaining part diverge qualitatively into different meters or lose their prosodic rhythm. This aligns with the Foroughic conception of rhythm. According to Sīrūs Shamīsā, the Foroughic rhythmic system is essentially a quasi-prosodic rhythm, where the meters of the lines do not necessarily align perfectly, but instead approximate various meters that create a harmonious sound when the poem is read as a whole.

In terms of language, besides using uncommon, archaic words like “shārib” (mustache), the poet deliberately disrupts her sentences by interrupting the narrative in each line. Various narrative elements in this stanza are abruptly halted and replaced by a new narrative without elaboration. This form is achieved by breaking the syntax, which goes against what would be in line with Forough’s patterns. Instead, broken syntax was a prevalent theme among poets of the 1990s and 2000s, reflecting the fractured and disturbed experiences of Iranian individuals in “the post-modern world.”

Theoretical texts and interviews from this period often reference various forms of syntactic deviations. Sa‘īd Zuhrahʹvand, categorized discussions around syntactic deviations in the poetry of this era into five types: 1) disturbances and disruptions of sentences or disruptions of the logic of language; 2) arbitrary word rearrangements within a sentence and disruptions of sentence elements; 3) omitting verbs to create suspension, and omitting the tense and the person; 4) using verbs, nouns, and adjectives contrary to grammatical rules; and 5) creating artificial derivatives.45Sa‘īd Zuhrahʹvand, Jarīyānʹshināsī-yi shi‘r-i dahih-yi haftād (Tehran: Rūzgār, 1395/2016), 258–61. Syntactic deviations during this period were embraced by various groups of poets, including Barāhanī and the young poets who participated in his workshops during the 1990s, Ali Bābāchāhī and the new generation of poets associating their work with the modernist traditions of Persian poetry in southern Iran, and the avant-garde poets known as the Seventies Poets.

Ahmadī’s approach to syntactic deviations in her work has evolved throughout her career. In her first collection of poetry, her experiments with syntax were limited to unconventional arrangements of sentence components that did not disrupt the prevailing regime of signification:

من خواب میبینم تمام جمله بعد

بیدار میشوم برای جمله بعد

در ایستگاهی که برف میآمد

روی همان صندلی که خم شده در دریا

پنجره را با دست نگه دار

میخواهم از هزار صفحه بیشتر بشوم

The whole next sentence, I dream

For the next sentence, I wake up

At the station where it was snowing

On the same chair that was bent in the sea

Hold the window with your hand

I want to become more than a thousand pages46Pigāh Ahmadī, Rū-yi sul-i pāyānī (Tehran, Nigāh-i Sabz, 1378/1999), 62.

In this example, Ahmadī employs delays in stating the direct object and prepositional object in the first two lines. By doing so, she manages to maintain the Foroughic rhythm of the lines as well as approximate a rhyme arrangement for the stanza. However, her approach toward syntactic deviation in her third and most celebrated book, These Days of Mine Are Throat, is notably more radical.

مرا بکُش سید!

پایین گلوست که پایین نمیرود میان من و خواهرم

چقدر خاک، لای گلو و النگویم بیا…

پایین صداست که پایین نمیرود…

Kill me, Sayed!

Down, it’s the throat that won’t go down between me and my sister

How much soil, between the throat and my bangles come…

Down, it’s the sound that won’t go down…47Ahmadī, Īn rūzʹhāyam, 40.

In these two very short stanzas, from a poem dedicated to the 2003 Bam earthquake, the poet disrupts her sentences by starting anew and leaving them unfinished, capturing the fragmented stream of thoughts one might experience during such a catastrophic event. As Barāhanī suggests, syntactic deviation and other forms of radical experimentation with the fundamentals of language stem from internalizing a crisis that impacts the poet. He writes, “I was broken into pieces, but I was not predisposed to ruin, so I internalized and absorbed that breaking into pieces within myself and my work.”48Barāhanī, “Nazariyah-yi zabāniyat,” 14. In her latest poetry collection, Intensity, published in Paris after her immigration, Ahmadī attains a profound state of internalization of the disaster. In the following stanza, one observes her extending her experiments with syntactic and grammatical deviations beyond the scope explored in her first three books:

فلِش به آینده، به فالش، به آیندگی!

فلِش به او که پشت چاقو، دریده میمانَد،

کف خیابان را به تیر میبندد

فلِش به اعتصاب تو در مرگ ما

خیال کن جایی

به رگ، کشیده شدی

و باد، نسلات را طوفانیده است49Pigāh Ahmadī, Shiddat (Paris, Nākujā, 2017), 23.

An arrow pointing to the future, to the off-tune, to the futurity !

An arrow pointing to the one who remains torn behind the dagger

And shoots down at the street

An arrow pointing to your strike in our death

Imagine somewhere

You’ve been dragged on a vein

And the wind has stormed your generation.

In this piece, she uses thenoun, “āyandigī” (futurity), which is an unconventional derivative from the noun “āyandah” (future). She also uses the verb “tūfānīdan” as a derivative of the noun “tūfān,” (storm) contrary to conventional grammar. This type of disturbed language is a performative choice by the poet to express the uncertainty an intellectual in exile may experience regarding “the future” and the turmoil caused by the upheavals experienced by her and her generation of artists, many of whom ended up living and writing outside Iran. That said, in Intensity, the poet takes a more moderate approach to syntax compared to These Days of Mine Are Throat. While still inclined to use ecstatic utterances to experiment with the potential of the Persian language and experimenting with artificial derivatives, she leans towards shorter and grammatically sound sentences, echoing Ahmadī’s style and reminiscent of Forough in tone. Yet, she endeavors to delineate clear boundaries between her poetry’s representation and how it diverges from the Foroughic tradition in the works of other female poets.

Ahmadī, while acknowledging Forough as the foremother whose work and life have been “imitated” by many women poets after her, at times excessively, adopts an opposing stance to what Forough epitomizes as a female poet. She contends that Forough is “the executor of women’s literature from the male perspective,” imbuing her poetry with the boldness derived from a male standpoint. Ahmadī suggests that Forough’s aesthetics are somewhat centered around men, as she had submitted her poetry to the male-dominated language of Persian poetry.50Pigāh Ahmadī, Shi‘r-i zan az āghāz tā imrūz (Tehran, Chishmah, 1384/2005), 25.

In other words, Ahmadī views Forough’s approach to experimenting with poetic language as conservative. Therefore, she advocates for overcoming the boundaries set by Foroughic poetry in terms of syntactic deviations. Ahmadī suggests that Forough, despite opposing the status quo, does not actively fight against it. Instead, she accepts the bleak and weary portrayal that the male-dominated modern literature has presented.51Ahmadī, Shi’r-i zan, 26.

One could argue that her opposition to Forough’s stance regarding the radical departure from patriarchal poetry is influenced by Barāhanī’s suggestions to Persian poets of the post-1990s. Barāhanī proposed:

It is necessary to alleviate fatigue by breaking the sentence, by removing priority and hierarchy, and paternalism of the sentence, by returning the sentence to its initial direction, by touching the word anew for the sake of poetry, and by placing the essence of language in the foreground, among other things.52Barāhanī, “Nazariyah-yi zabāniyat,” 15.

To recall and remember her poetic foremother, Ahmadī attempts to establish an intertextual relationship between her poetry and that of Forough while maintaining a revisionary approach by radicalizing her language through the use of ecstatic utterances and syntactic deviations:

بر این جمع بیقبا رحم آوردم و زکات شدم

باران و نان نداشتند

در این ابرها را باز و شاعری کردم!

منقاشی در خارشتر زدم

جایی که دستهای عاریه روییدهاند

خطی به طرز کشیدم.

Upon this naked assembly, I bestowed mercy and became zakāt [alms tax]

They had no rain or bread

I opened up these clouds’ doors and versified!

I stuck the burin in the alhagi,

Where borrowed hands have grown

I drew a line in a unique style.53Ahmadī, Īn rūzʹhāyam, 7.

One can compare the image of hands growing like plants with the following stanza by Forough:

دستهایم را در باغچه میکارم

سبزخواهد شد، میدانم، میدانم،میدانم

و پرستوها در گودی انگشتان جوهریم

تخم خواهند گذاشت

I plant my hands in the garden

They’ll grow, I know, I know, I know

And the swallows in the hollows of my inked fingers

Will lay their eggs.54Forugh Farrokhzad, Io Parlo Dai Confini Della Notte : Tutte Le Poesie ed. and trans., Domenico Ingenito (Milano: Bompiani, 2023), 654.

چه حافظهای در کاشیهای اصفهان آبیست

بر خواهران طولانی بیغاره میزنند و زنهای متعه نوحه میخوانند

امشب تمام پردههای مرا پاک میکنند خطیبان

فردا از قرائت این زندگی به سنگ خواهند رسید.

What a memory that is blue within the tiles of Isfahan

They scold the long-suffering sisters, and the concubines sing laments

Tonight, the preachers clean all my tableaus

Tomorrow, from reciting this life, they’ll reach the stone.55Ahmadī, Īn rūzʹhāyam, 12.

Additionally, the imagery of blue tiles and the voice of mourning echoes the following stanza from Forough:

پس آفتاب سرانجام

در یک زمان واحد

بر هر دو قطب ناامید نتابید

تو از طنین کاشی آبی تهی شدی

و من چنان پرم که روی صدایم نماز میخوانند…

So finally the sun

At a single moment

Didn’t shine on both poles in despair

You emptied from the echo of blue tiles

And I am so full that they pray upon my voice…56Farrokhzad, Io Parlo Dai Confini Della Notte, 676–78.

In the first example, the imagery of “borrowed hands” that have “grown” manifests the poetic legacy passed down from Forough, which the speaker nurtures and hopes will flourish in the future. The voice in this stanza asserts authorship by claiming to have “opened the doors of the clouds,” attributing the growth of these hands to the act of creating poetry. Furthermore, the speaker emphasizes “drawing” a distinct “line” between her poetry and that of her predecessors. In the second example, the recollection of “blue tiles” echoes imagery from Forough’s poetry, while the expressions of mourning and lamentation by the sisters and women continue Forough’s thematic voice.

By directly referencing Forough’s poetry and incorporating it into her own work through broken and rebellious syntax, as well as using self-referential language, Ahmadī attempts to create an antithesis to her foremother’s poetry. Harold Bloom suggests, young poets often fear their predecessors, viewing them like a flood that can overwhelm and stifle their creative voice. While every poet must engage with literary tradition, succumbing to this influence risks turning them into mere readers, rather than creators.57Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry, 2nd edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 57.

The foregoing analysis underscores the poets’ shared perception of poetry as a site of rebellion against patriarchal poetry. In addition to the anti-patriarchal motifs evident in their poems, their oeuvre serves a broader purpose: destabilizing linguistic norms and engendering new forms of signification. Both poets deftly navigate the complexities posed by their poetic antecedents and endeavor to establish connections with their poetic foremother in a manner distinct from their contemporaries. This distinctive approach not only contributes to the development of what this article attempted to formulate as Foroughic poetry but also diverges from the established tradition of modern women’s poetry shaped by patriarchal theories and historiographical narratives of Iranian modernists.