Deep-Rooted Rebellion: Contemporary Poetry of Iranian Women

Introduction

Is there such a thing as feminine or masculine literature?1This article acknowledges the diversity of sexual identities and orientations. However, it specifically addresses the binary categories of male and female. This focus does not imply the superiority of these genders in any way, nor does it endorse heteronormativity. Those who answer in the negative generally argue that analyzing women’s literary works through their relationship with men diminishes women’s achievements and encourages an objectifying perspective, as differences are often embedded in hierarchical frameworks. Conversely, those who advocate for a feminine language with distinct characteristics view its minority status as a source of strength. In contrast to the first group, they align with Elaine Showalter’s assertion that “androgynist poetics… demands a spurious ‘universality’ from women’s writing,”2Elaine Showalter, “A Criticism of Our Own: Autonomy and Assimilation in Afro-American and Feminist Literary Theory,” in Feminisms Redux: An Anthology of Literary Theory and Criticism, ed. Diane Price Herndl (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2009), 103. thereby placing it within a framework equal to male-authored works. This perspective, they argue, ignores the fact that the feminine subject within language cannot imagine itself outside the bounds of gender. To counter this “androgynist poetics,” they contend that the positive feminine element in literary experience must be emphasized. Consequently, they consider identifying and emphasizing these characteristics essential to strengthening literary tradition and advancing female aesthetics, ultimately challenging gender hierarchies.

Virginia Woolf was one of the first thinkers to address the concept of feminine language. In A Room of One’s Own, she envisages a sister for Shakespeare with the same talent and motivation, and states, “… who shall measure the heat and violence of the poet’s heart when caught and tangled in a woman’s body?”3Virginia Woolf, A Room of Ones’s Own (London: Hogarth, 1935), 37. The following poem by Khātirah Hijāzī expresses a similar sense of despair:

Above me

A lonely cloud weeps.

I think of the gallows of history:

The dull bastinado of musts and must-nots

And this tight feminine skin.

Who hears my voice?4Khātirah Hijāzī, Khvāhish mīʹkunam pīsh az man naʹmīr [Please don’t die before me] (Tehran: Nigāh, 1368/1990), 26.

According to Woolf, feminine language must contain different traits, as women cannot express their thoughts with the language that a patriarchal society provides for them.5Virginia Woolf, “Men and Women,” The Times Literary Supplement 948 (March 18, 1920): 182. The Essays of Virginia Woolf, ed. Andrew McNeillie (London: Hogarth, 1986), 2:67. Since the early twentieth century, writers, linguists, and philosophers have identified certain characteristics to this mode of expression. Today, language and gender studies are generally categorized into three main approaches: deficit, dominance, and difference—each having evolved historically.6For more on the three approaches, see Jane Sunderland, Language and Gender: An Advanced Resource Book (London: Routledge, 2006), 10–20. Some define a fourth dynamic or social constructionist approach, in which the other three approaches are used when necessary. See Jennifer Coates, Women, Men and Language (3rd ed., London: Routledge, 2013), 5–6. These approaches maintain a significant connection to feminism and its associated theoretical frameworks.

The deficit approach considers the language of men as the normative standard. Proponents of this theory criticize women’s language for its limited vocabulary, excessive formality, and overuse of exaggeration.7Otto Yesperson, Language: Its Nature, Development and Origin (London: George Allen & Unwin LTD, 1922), 248–50. However, they do not account for the underlying causes of these linguistic features. Radical feminists have attributed such characteristics to patriarchal dominance and gender-bound language, which they actively challenged in both theory and practice.8See Sunderland, Language and Gender, an Advanced Resource Book, 11–12. See also Coates, Women, Men and Language, 21.

In the mid-twentieth century, many linguists and philosophers examined the relationship between language and gender, suggesting that living and writing under the dominance of language and the rules that they called masculine produced these disparities. Robin Tolmach Lakoff’s Talking Power: The Politics of Language (1990) and Language and Woman’s Place (2004)9Robin Tolmach Lakoff, Talking Power: The Politics of Language (New York: Basic Books, 1990). Robin Tolmach Lakoff, Language and Woman’s Place, ed. Mary Bucholtz (London: Routledge, 2004). are the most influential works in this area.10See also Dale Spender, Man Made Language 2nd ed. (London: Pandora, 1990); Sara Mills, Feminist Stylistics (London: Routledge, 1995); Norman Fairclough, Language and Power (London: Longman, 1989). The issue of dominance in language persisted despite progress in the women’s rights movement. Emphasizing psychoanalysis and language, third-wave feminists, particularly French theorists, revisited the question of dominance. They explored how unconscious forces shape gendered language and examined the difference in the socialization process (or “entrance into language”) experienced by men and women. From this emerged the notion of écriture féminine. Hélène Cixous stated that “writing has been run by a libidinal and cultural—hence political, typically masculine—economy” and advocated that it is for women to write of the body as an act of rebellion.11Hélène Cixous, “The Laugh of the Medusa,” trans. Keith Cohen & Paula Cohen, Signs 1, no. 4. (Summer 1976): 879. Luce Irigaray analyzed the symbolic order of patriarchy in which men define femininity.12Luce Irigaray, The Sex Which is Not One (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985), 23. Judith Butler argued that the concept of gender has been imposed on women, reducing them to subjects within the historical narrative of feminism.13Judith Butler, “Women as the Subject of ‘Feminism’,” in Gender Trouble (London: Routledge, 1990). Butler’s theory of gender performativity, particularly their assertion that gender identity is constructed through repetitive linguistic and social practices, has clear implications for how we define poetic language. The stylistic features identified in women’s poetry—such as frequent questions or hesitations—when interpreted as performative strategies, become instrumental strategies of negotiations about gender identity within patriarchal constraints rather than merely reflecting subordination of its linguistic principles. Julia Kristeva wrote, “At the interior of this psychosymbolic structure, women feel rejected from language and the social bond… .”14Noelle MacAfee, Julia Kristeva (London: Routledge, 2004), 97. Each one of these thinkers contributed to the expansion of the concept of écriture féminine. According to their view, écriture féminine has certain characteristics which disrupt the masculine order of language known as the symbolic order.15For more on masculine dominance, see Pierre Bourdieu, Masculine Domination (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001). They conceptualize gender as a cultural construct, which is shaped by societal norms, conventions, and changes. This redefinition of gender transformed the fields of language and gender studies. As Coates observes, “In the past, researchers aimed to show how gender correlated with the use of particular linguistic features. Now, the aim is to show how speakers use the linguistic resources available to them to accomplish gender.”16Coates, Women, Men and Language, 217.

Poetry represents a departure from the symbolic order of language, and in this sense, it can be compared to écriture féminine. The signifying approach of poetic language, manifested through its deviation from the established standards of the symbolic order, serves as a distinct function: it has the capacity to disrupt the systematic mechanisms of symbolic language by creating new connections and generating new functions. Kristeva identifies the pre-linguistic space she calls the chora as foundational to the semiotic, which she contrasts with the symbolic order, or language proper.17Kristeva has taken these two aspects of signification for the two functions of language: language expressed logically (symbolic) and language that releases emotions and motivation (semiotic), which does not follow grammar. Semiotics is the place of subject before entering language. When the baby is in its mother’s arms (chora), it connects only with signs. See MacAfee, Julia Kristeva, 15–16. For Kristeva, while the semiotic is rooted in the chora, it is not identical to it; rather, it occupies a transitional space that disrupts and interacts with the symbolic. She argues that artists and, above all, poets maintain a dynamic relationship with the semiotic order. Cixous views poetry as the only form of language that can be considered “feminine,” because it draws its power from the unconscious, a borderless space where the oppressed may reside.18Cixous, “The Laugh of the Medusa,” 879–80.

Feminine poetry appears to rebel against two main constructs: language itself and the culturally defined concept of gender in language. In other words, the female poet seeks to enact a form of gender expression that can be described as textual performance. Therefore, certain recurring features in the language of female poets may be understood as stylistic markers of this poetics.]

Language Dominance and Feminine Intonation

This article assumes the existence of linguistic dominance—specifically, the dominance of male language, which is widely regarded the normative standard. In contrast, certain features have emerged in women’s poetry that we refer to as a “rebellion.” The dominance approach is grounded in the idea that power dynamics shape language use. Robin Lakoff, one of the most prominent linguists to explore the relationship between power and language, outlines in Talking Power (1990) fourteen characteristics of female language influenced by symbolic (masculine) language.19Lakoff, Talking Power, 204. These fourteen characteristics, originally formulated for spoken language, provide the first framework for this study. To use them for written language, the list has been modified through selective omission and adaptation. It includes: the use of incomplete sentences and ellipses, questions, hedges, indirect speech, gendered vocabulary, markers of gender identity, naming of the body, emphasis, and repetition.

Most of the characteristics seem to contribute primarily to the creation of tone. In other words, tonal variation is one of the most perceptible distinctions between female and male linguistic expression. Intonation is often the element cited when scholars assess the degree of femininity in a literary work. The “music” of speech, in turn, is a central mechanism for shaping tone. For example, extended syllables may signal the writer’s regret and remorse, or, when combined with a fitting atmosphere, they may convey a reflective or philosophical mood. In contrast, short and fragmented syllables often express restlessness or anxiety. The use of incomplete sentences and ellipses, which seem to index anxiety or emotional fragmentation, is more common in the poetry of women than that of men.20Since this article focuses on Iranian women’s poetry, any references to poetry specifically pertain to Persian poetry. Women’s frequent deployment of shorter sentences or clipped syllables should not be reduced to mere symptoms of linguistic deficiency; instead, these stylistic choices embody historically imposed constraints while simultaneously functioning as nuanced, deliberate acts of linguistic subversion or strategic accommodation.21See number 11 of Lakoff’s fourteen properties, Lakoff, Talking Power, 204. See also Coates, Women, Men and Language, 111, 115. “Don Zimmerman and Candace West (1975) found that 98 percent of women of interruptions in mixed sex conversation were made by males.” Quoted from Spender, Man Made Language, 43. For Zimmerman’s and West’s study, see Don Zimmerman and Candace West, “Sex Roles, Interruptions and Silences in Conversation,” in Language and Sex: Difference and Dominance, ed. Barrie Thorne and Nancy Henley (Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1975). In Iranian culture, as in many traditional cultures, women who speak loudly and assertively are not viewed positively, while silence and obedience are upheld as virtues. As a result, Persian women’s poetry rarely exhibits expressive long syllables and epic rhythms. Instead, one often hears a quieter, more restrained sound: abbreviated syllables, shortened phrases, and incomplete sentences that resemble whispered expression.

Other musical elements that contribute to creating a feminine tone include the rise and fall of intonation in interrogative sentences and rhythmic variation for conveying emotion. Vocalization and sound also influence the musicality of language and play a significant role in the expression of emotion. For example, in Persian poetry, the interjection of āh (an explanation of pain, sorrow, or longing) is frequently used to evoke a tone of sadness and regret. Such emotive sounds appear more frequently in Persian poetry written by women.

In addition to musical features, the use of hedges, ambiguity, and indirect speech is instrumental in shaping a feminine tone. While these elements do not contribute directly to the external musicality of language, they serve to align the speaker’s intention with the manner of expression, producing a form of internal harmony. Furthermore, by softening judgement and blame, they often reduce the certainty or assertiveness of speech.

None of these tonal effects is possible without careful diction. Each tone is supported by a specific vocabulary suited to its emotional register. Across various feminine tonalities, word choice connected to the feminine experience is notably more prevalent. For example, the word zan or “woman” appears more frequently in Persian poetry by women. However, some female poets deliberately avoid referencing womanhood, its associated suffering, or motherhood in their work. One explanation for this may be the constraints of limited lexical options. Such limitations can reduce the scope of feminine expression in poetry to domestic activities and household imagery.22The reason why we do not label poems reflecting the atmosphere of war as “masculine” is that, for us, the so-called poetry of men—and fundamentally the masculine world of poetry—represents the natural state of poetic creation, making its masculinity so implicit that it requires no additional labeling. Women’s vocabulary in poetry is largely shaped by their lived experiences. Accordingly, they tend to draw from language rooted in everyday life. In the context of Persian poetry, traditional lexical fields associated with women often include terms related to domestic labor, childbirth, clothing and accessories, female suffering, and gendered activities such as sewing and hairdressing, as will be illustrated below.

The frequency of the characteristics mentioned above reveals changes over time and can be analyzed to trace the development of a feminine poetic tradition. This study posits the existence of a distinct language specific to feminine poetry, emphasizing the importance of identifying and highlighting its features as essential to the literary and aesthetic coherence of this tradition. To enumerate and evaluate these characteristics from a stylistic point of view, a well-defined corpus is necessary. The present study’s corpus consists of ninety poems by fifteen poets, whose free-verse poetry was published between 1330/1951 and 1390/2011.23The selection of poets was made based on the number of book prints, awards given to poets, their fame and significance, as well as consulting experts in the domain of poetry: Furūgh Farrukhʹzād (1313–1345/1934–1967), Tāhirah Saffārʹzādah (1315–1387/1936–2008), Mīnā Dastʹghayb (b. 1322/1943), Batūl ʿAzīzʹpūr (b. 1332/1953), Khātirah Hijāzī (b. 1340/1961), Firishtah Sārī (b. 1335/1956), Nidā Ābkārī (b. 1343/1964), Nāzanīn Nizām Shahīdī (1333–1383/1955–2005), Ruzā Jamālī (b. 1356/1977), Grānāz Mūsavī (b. 1354/1973), Pigāh Ahmadī (b. 1353/1974), Rawjā Chamanʹkār (b. 1360/1981), Bahārah Rizāyī (b. 1356/1977), Rawyā Zarrīn (b. 1351/1973) and Sārā Muhammadī Ardahālī (b. 1354/1975).

It is important to note that female poets in contemporary Iran experience dual forms of oppression: one stemming from a patriarchal society and the other from a totalitarian religious government. Systematic governmental censorship has also led to certain stylistic features, such as increased use of indirect expression. Moreover, self-censorship and the male-dominated editorial processes in publishing houses often render some layers of such language inaccessible. What follows is a description of the poetic features found in the work of these poets.24For statistical data, see Gulālih Hunarī, ʿUsyān-i rīshahʹdār [Deep-rooted rebellion] (Tehran: Agar, 1400/2021), 159–65.

Of Being and Composing

The most prominent characteristic of women’s Persian poetry can be defined by two interrelated features: writing and being. Female poets frequently emphasize the act of writing in relation to their gender identity. The process of writing or composing a poem is often metaphorically linked to pregnancy and childbirth, suggesting that poetic creation is an embodied experience. These poets also frequently mention the moment of composition, the act itself, and the word “poetry,” highlighting its significance with both self-awareness and intentionality toward their audience.

In this context, the female poet consistently affirms her gendered identity through her work. This manifestation of gendered identity plays a pivotal role in the poetic act and can be seen as a form of performative authorship, an element less frequently observed in male-authored poetry. In the following excerpt, in addition to a mediation on the act of writing, the poem also gestures toward masculine dominance:

It is under the gaze of man

That woman

Became a sentence

She does not feel she has been seen

Neither do I, at times; what about you?

Me?!

I do not take a step

I get up from the buttons that fall

And as I close my eyes

All the sentences on earth become woman25Pigāh Ahmadī, Kādins [Cadence] (Tehran: Nigāh-i Sabz, 1380/2001), 8.

Allusions to gender, an important means of exploring heteronormative gender identity, appear in different forms in the poetry of Persian-speaking women, one of which is indirect expression. Often, linguistic markers signal that the poet is referring to herself, even when speaking about another individual or concept. This indirectness may serve protective functions: the poet might apply certain statements to herself cautiously or reveal information that challenges dominant ethical or cultural norms. For example, when describing a relationship with a beloved, the poet may frame the narrative through imagery that distances the experience from herself:

Turn around and, behind your back, open slowly

The closed eyes

A shadow accompanies you

Of a woman who breathes

From the roof of the bygones

The woman who lived with you

The woman who slept with you26Tāhirah Saffārʹzādah, Majmūʿah-ʾ i ashʿār [Collection of poetry] (Tehran: Pārs Kitāb, 1391/2012), 35–36.

While such techniques are not exclusive to women and are found in men’s poetry as well, their use in women’s poetry is often more charged. This is particularly evident when the word “woman” is used synecdochically to represent the self:

In the wave of your mirror

The image of a barren woman

Walks to the alley27Grānāz Mūsavī, Āvāzʹhā-yi zan-i bīʹijāzah [Songs of a woman without permission] (Tehran: Sālī, 1382/2008), 22.

In some instances, indirect speech also reflects the poet’s sense of alienation from herself:

Was the woman who turned into dust

In her shroud of awaiting and chastity

My youth?28Furūgh Farrukhʹzād, Īmān biʹāvarīm bih āghāz-i fasl-i sard [Let us believe in the beginning of the cold season] (4th repr. ed., Tehran: Murvārīd, 1355/1976), 46.

Another method of indirect expression is the articulation of hopes and desires through the voice of a woman other than the poet. In this way, female poets can express what they want without risking rebuke. This technique is particularly suited to expressing frustrations or rejections of the unwritten social codes imposed on women. At times, the source of indirect expression appears to emerge from within the poet, as though the poetic voice belongs not to the self but to another entity speaking through her. Such poems often reflect the poet’s inner emotional state and illustrate the dynamic relationship between the poet and poetic flow:

In me, too,

An old woman who beats inside with a broken stick

Was the breath-taker of your steps

Look inside me and see

How the dead and the alive are frightened of themselves 29Rawjā Chamanʹkār, Bā khvudam harf mīʹzanam [I talk to myself] (Tehran: Sālis, 1387/2008), 46.

In other words, by describing what occurs within, the poet establishes a degree of distance between the narrating self and the self being described.

Sometimes, the poet does not explicitly mention her womanhood but leaves textual cues to guide the reader toward discovering her gender. These cues often involve naming elements associated with the traditionally defined feminine world. For example, in the following poem, certain lexical choices reveal the poet’s gender identity, even in the absence of an explicit attribution:

With the green eyes of the ghazal, love cries

I pick a leaf from the autumn of Mister, Monsieur, Man

And I wipe my lipstick

Gentlemen!

When will the tornado

Leave your desert

So I can awaken the waterfalls30Batūl ʿAzīzpūr, Faslʹhā furū mīʹrīzand [Seasons disintegrate] (Essen: Nīmā, 1381/2002), 21.

The use of gender-marked vocabulary may be considered a key feature of feminine language. In a worldview where masculine language is seen as the default or “natural” form, references to male experience are often normalized and go unquestioned. For example, when a man poet writes about war or describes the body of his beloved, readers do not find it unusual, because the dominant linguistic paradigm considers it natural for men to write about subjects like poverty, death, women, and war.

There are different reasons a female poet might consciously or unconsciously reveal her gender in her poetry. One is the need to give voice to concerns shaped by gendered experience. The female poet encounters her gender, which often serves as the source of difficulty or oppression. She performs her social role through attention to gender: she recalls memories through a gendered lens, becomes a mother under the halo of gender, and resents the limitations and cruelties that she must bear due to her gender:

Not the most beautiful ornaments

Nor the most sweetly scented flowers

Not even your kisses

Nothing

Will free me from the sorrow of being a woman31Khātirah Hijāzī, Andūh-i zan būdan [The pain of being a woman] (Tehran: Rawshanʹgarān, 1371/1987), 12.

Often when women discuss themselves or other women in their poetry, they reveal both overt and subtle objections to societal norms. Virginia Woolf asserts that in a feminine text, not only is the presence of the writer as a woman evident, but also the presence of an oppressed woman who demands her rights. According to Woolf, this characteristic imparts to women’s writing an element absent in men’s writing. Consequently, once women’s issues are addressed and their anger alleviated, their perspectives may shift, and they no longer harbor bitterness, having attained the peace of mind traditionally associated with male geniuses.32Virginia Woolf, “Woman and Fiction,” in Collected Essays (London: Hogarth, 1966), 2:144–45.

Images of women who are hurt by and suffer from traditional society and married life, as well as those abused and abandoned by the law, are prevalent in women’s poetry. Such themes have become stylistic characteristics of women’s language. The frequency of these complaints varies across different situations and eras. For example, as evident in their poetry, most Iranian feminists of the post-Constitutional Revolution period (1284–1290/1905–1911), who were forcibly married at a young age and endured bitter lives after divorce, viewed married life as a prison and the husband the jailer. Numerous poems by Zhālah Qāʿim Maqāmī (1262–1326/1883–1948) were composed in such an atmosphere. Over time, issues like child marriage were addressed, giving way to other concerns such as child custody, as reflected in the poetry of Farrukhʹzād.33Child marriage in contemporary Iran gradually became taboo and unacceptable, especially in urban areas and among the middle class. This cultural shift was also reflected in the laws. The first law that imposed an age limit for marriage dates back to 1935 (Iranian Civil Code). Thus, during Farrukhʹzād’s lifetime, the problem of child marriage was somewhat controlled. Persistent unresolved problems continue to occupy the minds of female poets, to the extent that, in their writings, they have not yet transcended the influence of an “Foreign” in Woolf’s words.34Virginia Woolf’s expression for the interference of men and their dominance over the language and minds of women. See Woolf, “Women and Fiction,” 2:145.

An analysis of Iranian women’s poetry collections shows that, over the course of decades, women began to use more feminine vocabulary. In their poetry between 1330/1950s and 1340/1960s, there are fewer feminine words, but an abundance of words associated the masculine literary stereotypes. Parvīn Iʿtisāmī (1285–1320/1907–1941) is one of the first women to incorporate feminine words in her poems. Due to the didactic mode and classical style of her poetry, many have considered it masculine in nature; however, her poetry is not devoid of what may be characterized as feminine. No man other than Bishāq al-Atʿamah (d. ca. AH 840/1436) composed a satirical dialogue between a pot and a pan, or an onion and a garlic. Parvīn’s poetry efficiently represents the feminine world through language. Moreover, her didactic poetry and her emphasis on social responsibility of poetry marked a turning point from tradition to modernity.

A key question arises: why do contemporary poets, despite having higher levels of education, greater social mobility, and fewer societal expectations to engage in domestic tasks, use words such as “needle” and “pot” more frequently than poets who were largely confined to kitchens and sewing machines? If such vocabulary is not intended to mark distinction, what other motivations might underlie its use?

It appears that, from the early 1330/1950s to the mid 1340/1960s, women poets were deeply entangled in a literary culture dominated by masculine norms. For a celebration to which they were not invited, they dressed themselves according to the customs of the hosts. They were not granted access to formal literary education and when they were, it reinforced the dominant masculine ethos of Persian literature. Having been nourished on a millennium of male-authored texts, they naturally gravitated toward masculine stereotypes in their own creative expression. This may explain the relative absence of vocabulary reflecting womanhood in women’s poetry of that era. A prime example is the poetry of Furūgh Farrukhʹzād’s early work from the 1330/1950s. In Asīr (The captive), she pours her love soliloquies in the cup of the cupbearer and longs for kisses from the beloved. The archaic vocabulary of her first two books reveals her alienation from the poetic world she had just entered. Considering her boldness in expressing desire and emotion, her reliance on traditional literary forms appears not to reflect conservatism but lack of experience. She had entered a new world without her own language and was compelled to borrow from others.

By the 1350s/1970s, women had gained greater awareness and rights: they could vote, work outside the home, and engage more freely in public life. Women poets of this era, who were challenging traditional structures, appear more up to date in their themes and expressions. Interestingly, however, the feminine atmosphere in their poetry becomes less pronounced. Many of these poets, including Mīnā Asadī, Batūl ʿAzīzʹpūr, Qudsī Qāzīʹnūr, and Tāhirah Saffārʹzādah, became involved in political struggles and experienced a heightened sense of social engagement. Contrary to expectations, as women became more modern and moved away from traditional domestic roles, the use of feminine language increased among poets in later decades. This trend seems to be intentional. Gradually, and with the establishment of a distinguished group known as the “female poets” (shāʿirān-i zan), the inclusion of words related to domestic life and femininity developed into a recognizable style and poetic tradition, as the following analysis demonstrates.

Examining the vocabulary used in women’s poetry provides insight into their daily lives and environments, and offers valuable sociological and psychological perspectives. For example, words related to clothing evolve in tandem with social conditions across different periods. Batūl ʿAzīzpūr frequently uses the word “hair” in her early poetry, while Ruzā Jamālī often references the “headscarf” among other symbols of contemporary Muslim womanhood.35Batūl ʿAzīzpūr, Khvāb-i Laylī (Tehran: Ruz, 1351/1970); Batūl ʿAzīzpūr, Shiʿr-i āzādī (Tehran: Bīdārān, 1358/1979). Nidā Ābkārī blends the themes of hijab and exposure in the following poem:

She pulls a veil on her head

And hides her lights in her bruised nipples

Strands of hair get tied around her finger

And her heart is full of sewing needles36Nidā Ābkārī, Tajrubahʹhā-yi khām-i rustan [The raw experiences of sprouting] (Tehran: Ibtikār, 1365/1986), 36.

A significant portion of feminine vocabulary is associated with housework and the kitchen. Women, particularly poets of the past two decades, often refer to the domestic kitchen environment and the repetitive nature of housework with connotations of monotony, stillness, and idleness. Why are the words related to the kitchen so commonly used? Can this emphasis reflect a feminine narrative of life’s repetitive nature, or does it instead point to the unpaid and exhausting labor of housework? In this context, one could argue that women poets view it as their social duty to articulate this role. By expressing a sample of the oppression experienced they experience as women, they seek to raise public awareness. The following poem by Rawyā Zarrīn illustrates the constrained nature of women’s lives, culminating in a symbolic output that ends as garbage late at night. As Virginia Woolf remarks, “often nothing tangible remains of a woman’s day. The food that has been cooked is eaten; the children that have been nursed have gone out into the world.”37Woolf, “Woman and Fiction,” 146.

Blue lady

Washing the dishes is finished, and

The samovar and the light are turned off, and

Children are in bed, and…

Well,

Now, exhausted and leaning on this chair,

I close my eyes and think:

What has remained of today?

A bag of garbage and

A few pieces of broken and bloodied china,

And cut hands that burn without bergamot.

Today is gone too,

Without me being called the “blue lady.”38Rawyā Zarrīn, Zamīn bih awrād-i ʿāshiqānah muhtāj ast [The earth needs love spells] (Tehran: Payām-i Imrūz, 1382/2003), 108–9.

Beyond vocabulary rooted in the shared experience of womanhood, the explicit use of the word “woman” appears in nearly every poetry collection written by women. In contrast, such direct mentions—e.g., the word “man”—are rarely observed in the poetry of male authors. Consider, for example, the opening of Nusrat Rahmānī’s poem Manʹam [This is me], in comparison to the beginning of Furūgh’s Īmān biʹāvarīm bih āghāz-i fasl-i sard [Let us believe in the beginning of the cold season]:39Farrukhʹzād, Īmān biʹāvarīm, 11; Nusrat Rahmānī, Majmūʿah-ʾi ashʿār [Collected poems] (3rd repr. ed., Tehran: Nigāh, 1385/2010), 460.

At times, references to women’s gender appear in the titles of their poems or even the title of their collections. In contrast, the word “man” is not used with such emphasis, and, in many instances, is meant to signify human beings, as see in the following poem by Ismāʿīl Khuʾī:

What do they think about these men?

Could it be that

Beyond knowing

A pain has clawed

The hearts of the wealthy?40Ismāʿīl Khuʾī, Bar bām-i girdʹbād [On the roof of tornado] (Tehran: Ruz, 1349/1970), 33.

Compare Khuʾī’s poem to the following poem by Batūl ʿAzīzʹpūr:

Poetry is kept by

Women in baskets,

Pedestrians in pockets,

Children in the palms of their hands,

Rulers do not know.41ʿAzīzʹpūr, Shiʿr-i āzādī, 11.

ʿAzīzʹpūr distinguishes women from pedestrians and children. This separation may have been engraved on her unconscious, or she may have made it intentionally.

Another frequent theme in women’s poetry is the female body. Female poets often express a strong desire to describe their bodies, a feature that is usually not seen in men’s poetry. Among the poets studied in this study, Grānāz Mūsavī has written most extensively about the body and through the body, aligning Hélène Cixous’s call for women to write the body. A distinct physicality emerges in her poetry:

“I swear on the fig and the olive” that with this Gog people42The first line (fig and olive) is a reference to the Qurān, Sūrah al-Tīn, 95:1.

My tongue goes to adultery.

I must reach my margins

And reread the Magog text of my body.

All my bones are ruined.43Grānāz Mūsavī, Hāfizah-ʾi qirmiz [Red memory] (Melbourne: self pub., 1390/2012), 9.

Such narration of the body, along with women’s wish to assert their gender identity, signals a form of rebellion against the masculine conventions in describing women’s bodies. Historically, many women have expressed alienation from their bodies—an estrangement that can be traced to the longstanding cultural taboo against women speaking about their physicality. Persian literature abounds with male-authored descriptions of female bodies.44This discourse is so dominant that several literary genres have been formed based on it. One such genre is called sarāpā nivīsī [writing from head to toe], widespread from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries and mostly in the Indian Subcontinent. The poet would compose a masnavī, sometimes quite long, describing different body parts of the beloved from head to toe. By focusing on their own bodies, women poets challenge centuries of representation by the masculine pen and reclaim the right to describe and define their own physical selves.45Cixous, “The Laugh of the Medusa,” 876. According to ʿAbd Allāh al-Ghazāmī, this shift transforms the woman’s body from an object of sexual value into a cultural value, thereby contributing to a distinctive feminine literary model and cultural expression.46ʿAbd Allāh al-Ghazāmī, Zan va zabān [Woman and language], translated by Hudā ꜥAwdah Tabār (2nd repr. ed., Tehran: Gām-i Naw, 1395/2016), 104.

Despite these efforts, much of women’s writing remains confined to descriptions of hair and eyes, and references to other body parts deemed taboo are typically veiled in metaphor. The earliest known mention of the body by a female poet in Persian literature is by Rābiʿah Balkhī (d. AH 329/940) who writes:

I wish my body were aware of my heart

I wish my heart were aware of my body.47Rūhʹangīz Karāchī, Tārīkh-i shiʿr-i zanān az āghāz tā sadah-ʾi hashtum-i hijrī qamarī [History of women’s poetry from the beginning to the fourteenth century] (Tehran: Pazhūhishʹgāh-i ʿUlūm-i Insānī va Mutāliꜥāt-i Farhangī [Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies], 1394/2015), 146.

Rābiʿah has been praised for portraying the realistic emotions of women and for expressing earthly love.48Karāchī, Tārīkh-i shiʿr-i zanān, 139, 142. Her connection to her body is notably depicted in ʿAttār’s account of her tragic death. Rābiʿah falls in love with Baktāsh, her brother’s slave. When her brother learns of the affair, he severs her the veins in her hands and imprisons her in a bathroom. Bleeding and in darkness, Rābiꜥah composes poetry until dawn. Lacking writing tools, she inscribes verses on the walls using her own blood. By morning, she is found dead and her body surrounded by poetry.49ʿAttār-i Nayshābūrī, Ilāhīʹnāmah, ed. Muhammad Rizā Shafīʿī Kadkanī (Tehran: Sukhan, 1387/2009), 371 and after.

This story portrays a woman who remains a poet and a lover to her last breath. She speaks of her body, her love, and her desire, but remains unacknowledged.50ʿAwfī praising her said, “Though she was a woman . . . but” she was a woman who loved beauty and engaged in love and love making. See Muhammad ʿAwfī, Lubāb al-bāb, ed. Saʿīd Nafīsī (Tehran: Ibn-i Sīnā &ʿIlmī, 1335/1956), 294. It follows that the more a poet challenges the status quo, the more resistance she will encounter. The degree of backlash often correlates with the age and rigidity of the cultural tradition being challenged. In this context, women’s writing is an act of defiance. Writing about the female body not only challenges but aims to dismantle traditional norms. Such writing may provoke severe reactions from guardians of those norms, as evidenced by the sexualized readings of the life and poetry of Furūgh Farrukhʹzād. An aura of sexualized myths surrounds the biographies of prominent female poets. By emphasizing these female poets’ transgressions, society attempts to undermine their contributions to social activism.51Compare the amount of attention paid to the private lives of Furūgh Farrukhʹzād and Ahmad Shāmlū. Many know why Farrukhʹzād separated from her husband and the ups and downs of her life, but few have written about the two divorces of Shamlu before his marriage to Āidā. One could argue that before women writers attempted to change the social order, their first act of iconoclasm was their audacity to pick up the pen.

In traditional societies, any discussion of a woman’s risks transgressing a cultural taboo. Poets of the 1360/1980s adhered more strictly to these taboos than those of the 1380/2000s, while references to taboos in poetry from the 1370/1990s are notably scarce. Yet even the poets of the past two decades have not surpassed Farrukhʹzād in their engagement with such themes. This may be partially due to the differing social statuses of female poets in the post-Farrukhʹzād era. Recent social transformations have significantly reshaped women’s perceptions of their bodies. If most of these poets were influenced by Farrukhʹzād, at least in their early works, how can we explain the absence of such direct engagement with the body in their poetry?

The Incomplete End

The frequent interruption of women’s speech by men, or rather by the institutional power, has led women to adopt shorter and more elliptical sentences. This tendency in everyday language may stem from women’s shyness due to their limited social experience or fear of judgment. Fragmented sentences in writing can reflect a range of emotions, including anxiety, fear, despair, and frustration. The use of ellipsis, empty space, and broken words are manifestations of such incompleteness.

Throughout this study, it became clear that the use of ellipsis occurs with notable frequency in women’s poetry. In the works of certain poets, its recurrence is particularly pronounced. For example, Ruzā Jamālī uses 103 ellipses in one of her books, which contains forty-three poems.52Ruzā Jamālī, Barā-yi idāmah-ʾi īn mājirā-yi pulīsī qahvahʹī dam kardahʹam [To continue this police story, I have brewed coffee] (Tehran: Ārvīj, 1380/2001). The use of ellipsis at the end of a poem, which can suggest an unfinished narrative, occurs so frequently in the poetry of Nāzanīn Nizām-Shahīdī that it can be considered a defining element of her style. For example, in Bar sihʹshanbah barf mīʹbārad (It snows on Tuesday) (1372/1993), sixteen of twenty-seven poems end with ellipses. In Ammā man muʿāsir-i bādʹhā hastam (1377/1998) (But I am a contemporary of the winds), twenty-eight of the thirty-seven poems conclude in the same manner.53Nāzanīn Nizām-Shahīdī, Ammā man muʿāsir-i bādʹhā hastam (Tehran: Nīkā, 1377/1998); Bar sihʹshanbah barf mīʹbārad (Tehran: Nīkā, 1372/1993). Ellipses can also convey a sense of unease and anticipation, as one of their functions is to suggest the silent passage of time. A poet who uses ellipses or blank spaces implies a period of silence within her poem.

Awaiting and…

Don’t ask!

I will not say anything about my feminine worries,

Nor about awaiting, nor boredom.

But about you…

You are the crystallization of my dreams.

As a human being,

You are the interpretation of the prophets’ muddled dreams,

And the feathers of the future pigeons are in your sleeves.54Zarrīn, Zamīn bih awrād-i ꜥāshiqānah muhtāj ast, 13.

In rare cases, as in the following examples, the use of ellipses may suggest self-censorship. For instance, Khātirah Hijāzī leaves her narrative of a romantic encounter incomplete—like a film scene fading out at a critical moment:

I climb you up,

My heart hammers on your chest.

Your heart answers,

And finally…

We come.55Hijāzī, Khvāhish mīʹkunam pīsh az man naʹmīr, 10–11.

In the following poem, Muhammadī Ardahālī explicitly links ellipses with censorship:

Your poems were published—

The poems that were in my dreams.

Your poems were given a publication permit.

They thought that those ellipses were the footprints of Shahāb al-Dīn Suhrivardī.

My poems were rejected.

They said the shoulders of my poems

Smell like men’s cologne.

They told me to delete “your child”

And “the throbbing of my body.”

Any book that now gets published,

I suspect that

Somebody,

Somewhere,

Has become an ellipsis.56Sārā Muhammadī Ardahālī, Rūbāh-i sifīdī kih ꜥāshiq-i mūsīqī būd [The white fox who was in love with music] (Tehran: Āhang-i Dīgar, 1390/2008), 85–86.

Leaving sentences incomplete does not fit within the logic of conventional semiotic language and gestures toward the symbolic realm. Women’s frequent use of this technique is meaningful and can be interpreted as a form of effective silence. Given its prevalence, it must be regarded as a stylistic characteristic in women’s poetry.

Ask the Mirror

The use of questions in poetry is not intended to acquire information but to draw the audience into the poetic process. Interrogative structures engage the reader and intensify the presence of the speaker. This type of questioning, commonly referred to as the rhetorical question, can function as an “action sentence,” emphasizing a message and enhancing its emotional or persuasive effect.

Among the stylistic features observed, questions occur with particularly high frequency and can be considered an empathic element of women’s poetic language. At times, poet use questions as a form of polite or indirect speech; at others, simply to express bewilderment. In the collections under study, the predominant function of questions appears to be expressing doubt or fostering intimacy with the reader. Frequently, women poets articulate emotional experiences through questions as a means of deflecting potential criticism or judgement. This technique also enhances audience engagement. Among the poets examined, Ruzā Jamālī uses interrogative sentences with notable frequency, which may constitute a hallmark of her style.57She has 114 questions in Barā-yi idāmah-ʾi in mājirā-yi pulīsī qahvahʹī dam kardahʹam [To continue this police story, I have brewed coffee]. The use of ellipsis is also very frequent in this collection. In the corpus of this study, the number of questions and ellipses does not vary significantly.

It could be said that the extensive use of interrogative sentences is a characteristic of modern literature and shows that modern humans are in the state of perplexity. If we accept such a proposition, one would expect the rate of its use to be the same in the poetry of women and men. But women poets ask questions more frequently than their male conterparts. To check this hypothesis, four collections of men’s poetry were randomly selected. The findings reveal that questions are notably less prevalent in men’s poetry. For example, in Qatʿnāmah (1330/1951) [Resolution] by Shāmlū, only ten questions appear, nine of which are concentrated in the poem “Surūd-i buzurg” [The great song]. By contrast, Nāzanīn Nizām Shahīdī’s Ammā man muʿāsir-i bādʹhā hastam contains thirty-five questions across fifteen poems. Naturally, poems with certain subject matter may lend themselves more readily to questioning. However, when questions are distributed throughout a poet’s collection, they signal a stylistic and conceptual distinctions.

Identifying such distinctions sometimes requires quantitative evaluation—assessing the frequency of a given stylistic element. At other times, a qualitative evaluation, focusing on usage type, is more appropriate. Meanwhile, the distribution of questions is critical in defining a stylistic trait. A poet who deploys questions throughout a collection cannot be evaluated in the same way as one who uses them sparingly in a specific poem. In the sample analysis of men’s poetry, the reviewed works were Rasūl Yūnān’s Muvāzib bāsh! Mūrchihʹhā mīʹāyand [Be careful! Ants are coming] (1395/2011) with eighty poems and no questions; Garrūs ʿAbd al-Malikīʾān’s Pazīruftan [Acceptance] (1392/2014) with thirty-eight poems and twenty-four questions; and Mahdī Akhavān Sālis’s Ākhar-i shāhʹnāmah [The end of Shāhʹnāmah] (1338/1959) with thirty-five poems and twenty-four questions.

In many cases, the interrogative propositions in women’s poetry appear to serve as a rhetorical strategy for distancing the poet from the full responsibility of a direct assertion. In the following poem by Farrukhʹzād, for example, she implies that a window must be opened, but frames her declaration as a question:

Isn’t it time

For this porthole to open

Wide open?58Furūgh Farrukhʹzād, Tavalludī dīgar [Another birth] (5th repr. ed., Tehran: Murvārīd, 1348/1971), 115.

Fear or self-censorship may compel her to cast the assertion in the form of a question to avoid judgement. If a male poet were to convey the same message, it might read:

It is time

For this porthole to open

Wide open.

At times, the use of questions indicates the shortcoming of the speaker in understanding the atmosphere and relating to it. Such propositions are often rhetorical and suggest emotional disorientation. When a poem contains an abundance of questions, the reader sense despair or perplexity:

Where is my memory?

Where is my home?

Where is my laughter?

Find me in the tiptoes under the window59Chamanʹkār, Bā khvudam harf mīʹzanam, 28–29.

Questions can also serve to cultivate intimacy with the reader. A poet who persistently engages the audience with questions integrates them into the poem’s journey. Farrukhʹzād frequently uses this technique. In some instances, the question functions as a polite request, positioning the reader with respect and granting them the freedom to accept or reject the plea. Lakoff suggests that women often frame requests as questions in daily conversation.60Lakoff, Talking power, 30. For example, when Farrukhʹzād asks her “most unique beloved,” “Why do you always keep me at the bottom of the sea?”61Farrukhʹzād, Tavalludī dīgar, 115. she is not seeking information but expressing a desire for literation from suffering. The interrogative here is a plea disguised as a question. Farrukhʹzād mostly uses interrogative sentences for emphasis, though at times they reveal a wistful tone:

Between the window and seeing there is always a distance.

Why didn’t I look?62Farrukhʹzād, Īmān biʹāvarīm, 17.

The appended interrogative sentence—a question that follows a declarative statement—intensifies audience involvement and adds rhetorical weight. This technique also serves as a stylistic veil for emotionally charged or socially sensitive content. To provide only one example, Grānāz Mūsavī asks: “What’s left of us / But shadows watering the flowers on the blankets?”63Grānāz Mūsavī, Pāʹbirahnah tā subh (Tehrān: Sālī, 1387/2009), 95. Among the poets analyzed, Farrukhʹzād employs this device frequently, while Zarrīn tends to use emphatic and negative questions more than the other poets under discussion.

Emphasis and Repetition

Emphasis often proves more effective than repetition, and repetition is commonly accompanied by emphatic adverbs; thus, the two elements complement each other. Using a set of adverbs that Lakoff terms “intensifiers,” women increase the effectiveness of their sentences as a defense mechanism.64Lakoff, Language and Women’s Place, 47. At times, women convey this emphasis by choosing verbs or adjectives that describe the intensity of emotions. Farrukhʹzād frequently uses “chih” [such] to intensify her language.65According to Mary Ritchie Key (1972), Spender claims that women use the word “such” more frequently than men. See Mary Ritchie Key, “Linguistic behavior of male and female,” Linguistics 88 (August 15, 1972): 15–31, as cited in Spender, Man Made Language, 36. In the following poem by Chamanʹkār, the adverb “aslan” [at all] and its repetition emphasize the poetic persona’s rejection of her lover, which is incongruous with the surprising ending of the poem with an implicit longing expressed in the final lines:

Do not come to see me at all

Do not put the “I love you” in the red roses

Do not bring it to me

Do not think of me at all

Or of the amusing villa in the south

Do not develop headaches

Do not become nervous

Do not ring my doorbell, my phone, in my sleep, in my dream, in my privacy

Do not pour this much salt over my wound

Do not be at all

Having said that

If one day you find me

standing next to a strange, wrong road

Do not say a word

Do not be surprised

I must have come looking for you66Chamanʹkār, Bā khvudam harf mīʹzanam, 9–10.

The mechanism of power in language raises the question of why women, who attempt to reduce intensity in their language, use intense words when discussing certain desires and emotions. It appears that the combination of emphasis and repetition diverts the text from being definitive. This combination, when a balanced with the use of command verbs, may reflect oppression in women’s language. While there is insufficient evidence to establish a correlation between repetition and oppression, one can only intuitively assert that in many poems featuring repetition, a sense of anxiety is present. On the other hand, because repetition is a mechanism for developing a poem, analyzing the number of repetitions that indicate anxiety is challenging, if not impossible. Repetition manifests not only in words but also in syllables, sentences, phrases, stanzas, and even themes. In Farrukhʹzād’s poem “Īmān biʹāvarīm…” the sentences “time passed,” “the clock struck four times,” “it is windy in the alley” and similar phrases are repeated. One of the hallmarks of Farrukhʹzād’s style is the repetition of sentences or certain words for emphasis. Some of her most impactful poems begin or end with the repetition of a line twice. Typically, when a sentence or phrase is repeated twice, the writer’s intent is emphasis. The ending of the poem “Ān ārizūʹhā” [Those wishes] exemplifies this:

And that girl who colored her cheeks

With geranium petals, O,

is now a lonely woman

Is now a lonely woman.67The translation is from Michael Craig Hillmann, “Furūgh Farrukhʹzād,” In Women Poets Iranica (Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation, 2022). https://poets.iranicaonline.org/article/furugh-farrukhzad/

Another example from the beginning of ꜥArūsak-i kūkī [The windup doll]:

More than this, O, yes

More than this one can be silent68Farrukhʹzād, Tavalludī dīgar, 16,17.

Sometimes Farrukhʹzād combines repetitions with questions. For example, if the question signifies despair, the repeated question indicates retreat and helplessness. Another technique Farrukhʹzād uses to add emphasis is incorporating what are known in Persian as “adverbs of degree,” which indicate the extent of an action or quality and/or signify the entirety of something or a time frame: “All day, I was crying in the mirror,” “All my existence is a dark verse,” “They took all the naivete of a heart . . .”69Farrukhʹzād, Tavalludī dīgar, 117; Farrukhʹzād, Īmān biyāvarīm, 14.

The analyzed collections reveal that women often use repetitions of words in the initial stanzas, and their use of conjunction words is so prevalent that it denotes a stylistic feature for some poets. Such repetitions introduce some possibilities to the poem: they enhance musicality, aid in structuring fragmented poems, produce hypnotic, spell-like effects, and amplify the poem’s linguistic impact. The repetition of prepositions and conjunction words (usually “kih” [that]), pronouns (e.g., “man” [I]), and short sentences (like sidā-yam kun [call me]) at the beginning of a poem or a stanza is a unique technique. Employing this technique, in addition to enhancing musicality and preserving form, results in an indecisive tone. Farrukhʹzād can be regarded as one of the pioneers of this musical-semantic technique due to her frequent use of such repetitions in her opening stanzas. For example, in the following poem, this technique is applied to nouns:

Happy corpses

Bored corpses

Silent, thoughtful corpses

Well-mannered, well-dressed, foody corpses70Farrukhʹzād, Īmān biyāvarīm, 28.

In the subsequent lines, the emphasis on the wistful feeling from the passing of time is conveyed by repeating one verb:

I feel that the time has passed

I feel that the “moment” is my share of history pages

I feel that the table is a false distance in between

My hair and the hands of this sad stranger71Farrukhʹzād, Īmān biyāvarīm, 46.

Naturally, one of the aims of repetition is to indicate the passage of time, a recurring theme in Farrokhzad’s poetry. Such repetitions in her poetry are evident through the coherence of the conjunction words “va” [and] and “kih” [that]:

Nobody wants to believe that the garden is dying

That the heart of the garden has swollen up under the sun

That the mind of the garden is slowly getting empty of green memories72Farrukhʹzād, Īmān biʹāvarīm, 51.

The conjunction “that” in the poetry of poets after Farrukhʹzād, namely Zarrīn and Chamanʹkār, is used more prominently. Based on the works analyzed in this study, its use can be interpreted as a specific stylistic feature influenced by Farrukhʹzād’s poetry. However, substantiating this theory requires a separate study using a different corpus.

As previously discussed, repetition in feminine speech holds particular significance. Some researchers have noted the circular time in women’s poetry in contrast to the linear time in men’s.73Kristeva in “Women’s Time,” takes the expression of father’s time and mother’s species from James Joyce. “‘Father’s time, mother’s species,’ as Joyce put it. When evoking the name and destghany of women, one thinks more of the space generating and forming the human species than of time, becoming, or history.” See Julia Kristeva, “Women’s Time,” trans. Alice Jardine and Harry Blake, Signs 7, no. 1 (Autumn 1981): 15. In the lives of many women, matters are more repetitive, from menstruation cycles to daily and routine housework:

And I am repeated

I am repeated

I am repeated repeatedly

Periodically74Ruzā Jamālī, Dahan kajī bih tu [Grimace to you] (Tehran: Naqsh-i Hunar, 1377/1999), 59.

Oral literature, including work songs, tales, lullabies, love songs, and so on, was considered part of feminine literature in the past. One of the features of these literary genres was repetition. Women have frequently used this technique in lullabies, which are among their oldest compositions. Repetition in women’s poetry happens so naturally that it often goes unnoticed. To women poets, repetition is a code from the world of lullabies: the unmistakable rocking of the cradle, that is the safe and open world of the future.

Indecisive Outlook

A hesitant tone is often considered a characteristic feature of feminine speech. Many argue that the linguistic markers of hesitancy and doubt in women’s expression result from their fear of judgment. Based on the works studied, it appears that such a tone in women’s poetry arises from a lack of confidence and mechanisms of dominance. The verb phrase “I don’t know,” the adverbs “perhaps,” “maybe,” and the expression “as if,” as well as interrogative constructions in general can suggest indecisive tones.75Spender calls the tools of doubt and hesitancy as qualifiers and according to studies by Hartman (1976) women use more qualifiers such as “perhaps.” See Maryann Hartman, “A Descriptive Study of the Language of Men and Women Born in Maine around 1900 As It Reflects the Lakoff Hypotheses in ‘Language and Women’s Place.,’” in The Sociology of the Languages of American Women, eds. B.L. Dubois and I. Crouch, P.I.S.E. Papers, IV (San Antonio, Texas: Trinity University, 1976), 81–90, as cited in Spender, Man Made Language, 35. Among the poets studied, Rawyā Zarrīn demonstrates the highest frequency of doubt and hesitation in her poetry:

Perhaps this empty space

Has been the photo of wind in a cage

Perhaps it has been a mirror

In front of this silent, hard, stone squad

Perhaps this

Is the picture of the grave of an unknown man

In the winter.76Zarrīn, Zamīn bih awrād-i ꜥāshiqānah muhtāj ast, 42.

According to Rizā Barāhanī, the use of “perhaps” in Farrukhʹzād’s poetry was intended to create a distinctively feminine outlook. Barāhanī accurately identifies the slippery outlook in Farrukhʹzād’s depiction of life, and due to the abundant use of “perhaps,” refers to it as an “indecisive outlook.”77Rizā Barāhanī, Talā dar mis [Gold in copper] (Tehran: Chihr, 1344/1966), 158. Farrukhʹzād quite frequently uses expressions of doubt and indecisiveness such as “as if” and “like.” While the use of expressions of doubt in a sentence may not inherently carry particular significance, they become meaningful when used excessively or redundantly. For example, in the following poem by ʿAzīzʹpūr, removing “as if” would not affect the meaning:

Just when this sun

Breaks the fog’s umbrella

And throws the red rose to you

And the whisper to me

It means as if this world

Is still not forsaken

That is as if the horizon

Is not the stone fence of your short sky78ʿAzīzʹpūr, Faslʹhā furū mīʹrīzand, 37.

Sometimes, the presence of a doubtful tone reflects the poet’s doubt about an event happening to her or a lack of sufficient knowledge about herself or her environment. For instance, in the following poem, the use of the verb phrase “I feel” prior to the act of sinking reflects Zarrīn’s lack of precise understanding of what is happening to her until she begins to drown a few lines later:

Help!

I feel I am sinking up to my throat

In the filth of the sacred cows’ stable

Help!

I feel: I am

drown

in

g79Zarrīn, Zamīn bih awrād-i ꜥāshiqānah muhtāj ast, 140–41.

The use of “perhaps,” known in Persian as the “adverb of doubt,” is the most frequently occurring element that produce doubt in women’s poetry.

Disobeying Standard Language

While conducting this research, a noteworthy feature was observed, which may not stem from the linguistic command but instead seems to oppose it. A curious feature of women’s poetry in the 1370/1990s and 1380/2000s is the repeated use of non-Persian words, written in Persian script or even in the Latin alphabet; a characteristic rarely seen in men’s poetry of the same period. This tendency in women’s poetry may be attributed to the increased availability of world poetry in Persian translation, and the advances in women’s lives and education, which have enabled them to learn foreign languages or live abroad. Women’s inclination toward vernacular language, partly due to their penchant for simpler syntactic structures and partly influenced by Farrukhʹzād’s legacy in feminine poetry, may also contribute to the frequent presence of foreign words. Many of these words are established in spoken Persian and are used in everyday language.

Regardless of the primary cause for women’s strong tendency to incorporate foreign vocabulary, there appears to be a hidden motivation as well: a kind of rebellion against the official language. By penetrating the official language, women challenge the status quo. As a principal tool in perpetuating dominance, the status quo becomes accessible to women and, at times, loses its credibility and authority. The use of foreign words also challenges social norms and serves as an outlet for disrupting and destabilizing the dominant regime of language. Muhammadī Asl argues that “by using more English words, [women] both display their disobedience to the national male language and seek status through their command of the international language.”80ʿAbbās Muhammadī Asl, Jinsīyyat va zabānʹshināsī-i ijtimāʿī [Gender and sociolinguistics] (Tehran: Gul Āzīn, 1399/2011), 81–83.

Am…en!

A voice is crumpled more than paper

A veinless hand twists letters hurriedly

The world’s pace got halted

And “The Alphabet” happened in my language81Ahmadī, Kādins, 15. The line in quotation marks is originally written in English in the poem.

Most poets write English words using Persian orthography. These words are often names of people, places, books, or songs and are typically well-known enough for readers to recognize. Occasionally, poets include unfamiliar words, phrases, or complete sentences written in English.

Today when my Russian kettle whistles again

I brew Kolkata Chai

Belgian sugar cubes

Wait by the English cups

“Let’s talk about love.”82The title of a 1997 album and song by Celine Dion.

It is a verse descending

From my Commonwealth record player83Rawyā Zarrīn, Man az kinār-i burj-i bābil āmadahʹam [I have come from side of the Tower of Babel] (Tehran: Nīlūfar, 1384/2006), 58.

Many poets have written the tittle of their poems in English. Some have tried to be innovative by using an English word with Persian auxiliary verbs such as “kardan” (to do) and “shudan” (to become). This technique has led to more innovation as in the following poem using the English “T” denoting the pronunciation of the word mop in Persian:

I do not T, sir 84Zarrīn, Man az kinār-i burj-i bābil āmadahʹam, 57. In Persian, “to T” [tay kishīdan] means to mop, a verb derived from the T-shaped mops.

Some innovations are even more intricate. In the following example, the poet creates a pun by altering the French spelling of “Jeanne d’Arc” to “Jeanne Dark,” using the English word “dark” to invoke imagery of darkness and juxtapose it with fire’s illumination:

I have become Jeanne Dark

Yet all that fire

Will not burn me anymore85Rawjā Chamanʹkār, Sangʹhā-yi nuh māhah [Nine-month stones] (Tehran: Sālis, 1382/2003), 26, 42–43.

Except for a single long poem of Tāhirah Saffārʹzādah in the collection of Tanīn dar diltā [Echo in Delta] (1349/1971), which resulted from her extended stay in the United States, the incorporation of non-Persian words in Arabic or Latin scripts did not become a noticeable trend until the 1370s/1990s. Since then, it has grown increasingly common and has become a feature of women’s poetry.

Furūgh Farrukhʹzād’s Influence on Contemporary Persian Poetry

“And I am so full that they pray on my voice …”86Farrukhʹzād, Īmān biyāvarīm, 28.

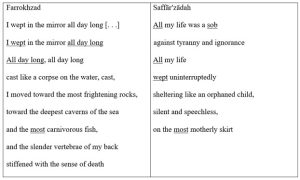

Perhaps this line from “Let Us Believe…” is not far from reality, especially considering that almost all the poets examined in this study were influenced by Furūgh Farrukhʹzād’s poetry in at least one or two of their early poems. Poets typically adopt formal structures while incorporating their own vocabulary. To understand her imitated forms, consider the following poem by Saffārʹzādah:87Furūgh Farrukhʹzād, Another Birth, Selected Poems, trans. Hasan Javadi and Susan Sallee (Emeryville, CA: Albany Press, 1981), 48, 50; Saffārʹzādah, Majmūꜥah-yi ashꜥār, 483.

In both poems, extended weeping is a central motif. The use of the superlative adjective “most motherly,” the act of crying in a duration, whether across a day, a year, or a lifetime, and the repetition of the word “all,” which shows the passage of time, all Farrukhʹzād’s influence on Saffārʹzādah.

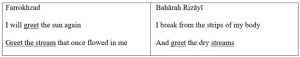

Farrukhʹzād can be regarded as a form-defining poet. The structures she created are so close to the natural music of speech that they readily permeate the language of subsequent poets. In fact, it is the cadence of natural speech that is sculpted in Farrukhʹzād’s poetry, flowing so organically that it easily seeps into the poetry of her successors as demonstrated below.88Farrukhʹzād, Tavalludī dīgar, 157; Bahārah Rizāyī, Ānītā, ꜥArūs-i chāhārʹfasl-i sukūt [Anita, the bride of the four seasons of silence] (Tehran: Sīmrū, 1378/1999), 60.

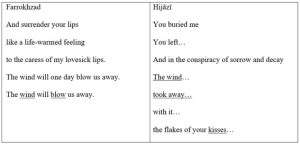

A significant number of female poets also adopt Farrukhʹzād’s frequently used vocabulary, which is distinctive to her poetic style. This includes words such as light, mirror, garden, window, and associated words pairings in Persian, such as wind and kiss, wind and destruction, among others.89Forough Farrokzad, Sin, Selected Poems of Forugh Farrokzad, trans. Sholeh Wolpé (Fayetteville: The University of Arkansas Press, 2007), 35; Hijāzī, Khvāhish mīʹkunam, 43.

Using words that have already been marked by another poet situates the influenced poet within the poetic context and outlook of the original poet. For example, Farrokhzad has expanded the meaning of the word garden; thus, our interpretation of this word in modern Persian poetry carries additional connotations. The same applies to the word window:90Farrukhʹzād, Tavalludī dīgar, 157, Nidā Ābkārī, Az rāh-i sāyahʹhā [Of the shadow’s path] (Tehran: Ibtikār, 1371/1991), 81.

Farrukhʹzād uses combinations of words that have become associated with her due to their unique phrasing. Examples include “simple complete women” and “simple excuses for happiness.”91Farrukhʹzād, Tavalludī dīgar, 111, 158. Because such combinations were not commonly used, their appearance or the appearance of similar constructions modelled after them suggests the poet has been influenced by Farrukhʹzād. Prior to her work, poets might have written “excuses for a loving life” or “happiness,” but “simple excuses” was rarely used. This linguistic marking and the creation of numerous innovative expressions and meanings are features characteristic of major poets. In the process of such linguistic innovation, new combinations often encode of the poet’s thought processes, and, on a broader level, present her worldview. For example, the phrase “simple excuses for happiness,” together with the criteria for happiness that are dispersed throughout Farrukhʹzād’s poetry, are rooted in her worldview. Some defining characteristics of “simple happiness” include wistfulness, unattainability, indefinability, and applicability. Farrukhʹzād elevated the idea of “simplicity” to a conceptual status. Valuing simple routines, and perceiving and performing them with fresh awareness, is a practice that Farrukhʹzād established. Woolf observes that women often seek to transform established systems of value, and one way they do so is by assigning significance to what men belittle and diminishing what men traditionally regard as important.92Woolf, “Women and Fiction,” 146. In this context, Farrukhʹzād’s poetry re-performs the everyday routines of women’s lives—for example, portraying “a lonely woman, on the threshold of a cold season”—in ways that resist narrative closure or resolution. At times, she even makes simplicity sacred:

Give me shelter you simple complete women

Whose delicate fingertips trace on your skin

The pleasurable movements of a fetus93Farrukhʹzād, Tavalludī dīgar, 120.

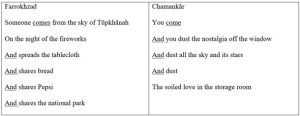

The admirable representation of simplicity is a stylistic feature of Farrukhʹzād’s poetry. One of the elements that enables this representation is her use of spoken language. Following her lead, many poets began to incorporate spoken language into their own work to convey simplicity. Among the poets selected for this study, many can be categorized as practitioners of the spoken language style. Hence, their association with this stylistic group has to the resemblance of their poetry to Farrokhzad’s poetry. As the example below shows, nearly all the poets examined in this study present simple subject matters of life in most of their poems.94Farrukhʹzād, Īmān biʹāvarīm, 71, Rawjā Chamanʹkār, Raftah būdī barā-yam kamī junūb biʹāvarī (Tehran: Nīm Nigāh, 1386/2002), 34.

Characters like the rebellious woman, the woman who articulates her emotional needs, and the individual who is content merely to observe life without expectations are all creations of Farrukhʹzād. In her early poems, she, too, reproduced stereotypical figures, such as the lonely mother and the oppressed woman. However, in her later works, she introduced new discourses, one of which features the audacious woman who rises against tradition, arguably one of her most enviable and costly creations. Following Farrukhʹzād’s legacy, we witness a heightened sense of individuality in women’s poetry.

Although the poets who came after Farrukhʹzād are indebted to her diction and marked subject matters, it is generally her worldview that has been transmitted to subsequent generations of women poets. Her outlook, a blend of rebellion and surrender, has deeply influenced their poetic sensibilities. Despite the apparent simplicity and intimacy of language in women’s poetry since the 1370s/1990s, there exists an underlying complexity, coupled with a spirit of rebellion, that conveys deep sorrow.

Farrukhʹzād’s resolution to the tension between rebellion and surrender culminates in her ultimate discovery: the necessity of loving madly. When does this occur? When her “faith is hanging from the loose rope of justice!” This realization forms the essence of Farrukhʹzād’s poetic spirit. At the peak of her creative and emotional power, she can no longer continue to fight, she finds no solace but in love.

Conclusion

Men on motorbikes

Swerve on the way to my songs.

Look how all the words in my poetry

Are constantly coughing,

As if in this highway

The light is always red,

And my language does not grow green.95Muhammadī Ardahālī, Rūbāh-i sifīdī kih ʿāshiq-i mūsīqī būd, 34.

In the above poem by Sārā Muhammadī Ardahālī, many of the features commonly associated with contemporary women’s poetry are present: emphasis, doubt, ambiguity, reference to gender, and finally male dominance over language. The characteristics of feminine poetry can be classified into two groups:

- Characteristics that have appeared in women’s language through the internalization of male linguistic and ideological dominance. The most prominent of this group is a tone of doubt. Other features contributing to this tone include the excessive use of questions, ellipses, incomplete sentences, conditional tenses, repetition, and emphasis.

- Characteristics that have emerged in resistance to male dominance over language, disrupting the logic of the dominant discourse. These include the use of taboo expressions and non-native words, interference with the formal script, references to the female body, and discussions of the limitations and sorrows imposed on women.

Given that interrogative sentences and ellipses occur most frequently, it seems there remains a long road ahead in addressing linguistic inequalities. Nevertheless, the use of defiant features, such as non-native words, has gradually increased in women’s writing. Likewise, the frequency of female-related words, deployed as resistance against narratives of inferiority, has risen significantly.

Poets of the 1380s/2000s, building on a literary tradition developed over the past fifty years, have cultivated a distinct style that may be described as feminine style in contemporary Persian poetry. Their style foregrounds women, the female body, emotional and physical pain, desire, and the everyday experiences of women under the prevailing social dominance. It also demonstrates a marked tendency toward modernity, made evident through both language and form. These poems are often translatable and diverge from the mainstream canon.

While poetry of the 1330s/1950s and 1340s/1960s was dominated by masculine stereotypes, the act of writing poetry itself often constituted a form of resistance to structure. Revolutionary literature—predominantly masculine in tone—continued to shape women’s poetry during the 1350s/1970s. In the 1360s/1980s, women began to awaken creatively, though their voices still carried tones of sadness, passivity, and disorientation. In the 1370/1990s, a clear rebellion emerges in women’s poetry, reflected in faster rhythms, frequent repetition, emphasis, and expressions of aggression. The Persian poetry of the 1380/2000s draws from these past traditions to evolve a nascent but growing poetic identity. It uses abundant repetition for musicality, conveys a poignant sense of sorrow mixed with balanced aggression, emphasis, and a language of command, contests patriarchal norms by challenging formal language, and amplifies its femininity.

From the perspective of linguistic power dynamics, many features of feminine language are often viewed as weaknesses—assessments that arise from a society from a society shaped by the dominant power structures. However, by challenging the evaluative mechanisms, it becomes clear that devaluation is less about gender and more about the speaker’s position within the power hierarchy. Identifying and emphasizing the features of feminine language can reveal the coercive nature of the dominant discourse. The more we understand the gendered ideologies embedded in a society’s culture and history, the better we can interpret and transform them.