Jahān Malik Khātūn: Poetry, Life and Mediaeval Reception*

Her Life in Shiraz

Jahān was an Injuid princess, and daughter of the ruler of Shiraz, Masʿūd Shāh (r. 736/1336-739/1339).1Dick Davis, trans., The Mirror of My Heart: A Thousand Years of Persian Poetry by Women, trans. Dick Davis, 1st bilingual edition, first publ. 2019, repr., (Washington D. C.: Mage, 2020), 49. As the name of Jahān Malik Khātūn recurs numerous times in this book, for the sake of brevity, I use the shortened version, Jahān, instead of her full name. She was the only child of Masʿūd Shāh to reach adulthood.2Muʿīn al-Dīn Natanzī, Muntakhab al-tavārīkh-i Muʿīnī [Selected chronicles of Muʿīnī], ed. Jean Aubin (Tehran: Kitābfurūshī-i Khayyām, 1336/1957), 174–75. All we know of her mother is that she was a descendant of Rashīd al-Dīn Fazl Allāh (d. 718/1318), a vizier in Ilkhanate Iran3Sabihe Koch, “Jahān-Malik Khātūn,” in The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Medieval Women’s Writing in the Global Middle Ages, 2. and the Chubanid of Azerbaijan.4Dominic-Parviz Brookshaw, “Jahān-Malik Khātūn,” in Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2012, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/shiraz-i-history-to-1940 Jahān was married to a nadīm (boon companion) and drinking friend of her uncle.5Davis, The Mirror of My Heart, 49. According to the Tazkirat (biographical anthology) by Dawlatʹshāh (d. 900/1495 or 913/1507), her husband’s name was Khvājah Amīn al-Dīn, and he was an influential vizier of Shāh Abū Ishāq.6Dawlatshāh bin ʿAlā al-Dawlah Bakhtīshāh al-Ghāzī of Samarqand, Tazkirat al-shuʿarāʾ [Memoirs of the poets], ed. E. G. Browne (London-Leyden: Luzac and E.J Brill, 1901), 290. The Iranian literary historian Zabīh Allāh Safā claimed that Khvājah Amīn al-Dīn was not Shāh Abū Ishāq’s vizier, but a companion who played a role in the affairs of his kingdom, and was hence given the title ‘vizier.’7According to Safā, Shāh Abū Ishāq’s vizier was Rukn al-Dīn ʿAmīd al-Mulk. See Zabīh Allāh Safā, Tarīkh-i adabiyāt dar Īrān [History of literature in Iran] (Tehran: Firdaws, 1369/1990), 3:1049.

We know very little about Jahān’s private life. Dick Davis postulates that when read in an autobiographical light, some poems in Jahān’s Dīvān might be considered references to her unhappy marriage. Since her husband spent much of his time with her uncle, it may not be far from the truth to assume that these poems indicate a largely absent intimate partner. The rest of our scant knowledge about her private life, which is partly reflected in her poetry, concerns major contemporary incidents in the history of Shiraz.8Davis, The Mirror of My Heart, 24, 49.

Before Shiraz came under the rule of the Īnjū dynasty, it had gone through a series of incidents resulting in civil unrest and political instability. After facing heavy taxation by the Mongols, repeated pillage by local rulers, and misrule by corrupt officials, Shiraz was a declining city. Around 100,000 lives were lost due to the drought of 683/1284–686/1287 and the subsequent famine. Another 50,000 people were killed by diseases such as measles in 696/1297.9A. Shapur Shahbazi, “Shiraz i. History to 1940,” in Encyclopædia Iranica, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/shiraz-i-history-to-1940. After this, Shiraz saw some improvement due to the charitable activities and maintenance of religious buildings of two Mongol women, Ābish Khātūn and her daughter Kurdujīn, but the peace did not last long.10Kurdujīn was the ruler of Fars between 719/1310 and 729/1320 or 730/1321. See Zabīh Allāh Safā, Tarīkh-i adabiyāt dar Īrān, 3:1046. The Īnjū rulers of Fars, Sharaf al-Dīn Mahmūd Shāh and his son Abū Ishāq, engaged in a power struggle during the late Ilkhanid period, causing more destruction and civil disorder.11Shahbazi, “Shiraz i. History to 1940.” This grave political crisis had a catastrophic impact on Jahān’s life.

Jahān faced a series of tragic events, starting when her father was assassinated in 743/1342. Her uncle, Abu Ishāq, avenged this assassination, and then became the ruler of Shiraz. Within a few years he was overthrown by Muzaffarid Mubāriz al-Dīn Muhammad (718–765/1318–1363), who murdered all the male members of Jahān’s family in 754/1353. In the aftermath of this incident, she was imprisoned for some time, and on being released was exiled from Shiraz.12Davis, The Mirror of My Heart, 49. Whether her husband was murdered or not is unknown. This was the end of Jahān’s convenient courtly life, as she was left without assured provision or support.13Koch, “Jahan Malik Khātūn.”

These catastrophic incidents shaped the context in which Jahān lived and wrote her poetry. The stifling religiosity imposed during the dark years of Mubāriz al-Dīn’s rule brought the cultural development and vibrancy of Shiraz to a stop.14Bahāʾ al-Dīn Khurramʹshāhī, “Hafez II: Hafez’s Life and Times,” in Encyclopaedia Iranica. Under the strict Islamic prohibitions enforced by this cruel warlord, wine and music were banned, and the wine-shops that had flourished during Abū Ishāq’s lax reign were closed15Dick Davis, trans., Faces of Love: Hafez and the Poets of Shiraz (Washington, DC: Mage, 2019), xv. In a rubāʿī (quatrain) attributed to him, Mubāriz al-Dīn’s son, Shāh Shujāʿ (r. 758/1357-786/1384), gave his father the sobriquet of muhtasib-i shahr (morality police of the city), due to his puritanical severity.16Khurramʹshāhī, “Hafez,” in Encyclopaedia Iranica. The people of Shiraz also used this nickname as a term of contempt for their new ruler.17Davis, Faces of Love, xv. The term muhtasib, which appears in the poetry of Hāfiz (d. about 792/1390), is probably derived from the same pejorative term used to criticise the hypocrisy of Mubāriz al-Dīn,18Khurramʹshāhī, “Hafez,” in Encyclopaedia Iranica. which did not last long.

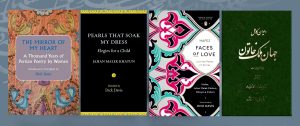

Figure 1- From leftFrom left: The Mirror of My Heart: A Thousand Years of Persian Poetry by Women, trans. Dick Davis; Pearls that Soak My Dress: Elegies for a Child, trans. Dick Davis; Faces of Love: Hafez and the Poets of Shiraz; and a collection of Persian poetry in the original language.

This period of darkness in the history of Jahān’s city came to an end in the fifth year of Mubāriz al-Dīn’s brutal rule over Shiraz, when his own son, Shāh Shujāʿ, had him blinded and deposed. Shāh Shujāʿ imprisoned his father in Bam (near Kerman), where he passed away.19Davis, Faces of Love, xv. Shiraz benefited in several ways from Shāh Shujāʿ coming to power. He averted the danger of Timur’s attack on the city in 784/1382 by appeasing him with valuable offerings.20Shahbazi, “Shiraz i. History to 1940,” in Encyclopædia Iranica. Shāh Shujāʿ also reversed many of his father’s extreme policies, so that wine and music reappeared on the city streets. Jahān and her prominent contemporaries, Hāfiz and ʿUbayd Zākānī (d. ca. 770/1370), all returned to Shiraz. They all wrote poems in praise of Shāh Shujāʿ, indicating their respectful relations with the new ruler, who brought stability to the city during a reign of more than twenty years.21Davis, Faces of Love, xv.

Manuscripts and Critical Editions

The only critical edition of Jahān’s Dīvān is based on three available manuscripts of her poetry collection. One of these manuscripts is available in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Supplément persan 763) and is the most complete version of the Dīvān.22Jahān-Malik Khātūn, Dīvān (Tehran: Zavvār, 1399/2021), x. This edition consists of 15,806 couplets, including 1,656 ghazals or love lyrics (a total of 14,552 couplets), 579 rubāʿīs or quatrains (1,158 couplets), one tarjīʿ-band or strophic poem (55 couplets), and several qitʿas or fragmentary poems (141 couplets). The book includes a preface, and two poems expressing God’s praise by alluding to His Oneness (tawhīd) and paying homage to the prophet Muhammad.23Parvīn Dawlatʹābādī, Manzūr-i khiradmand: Jahān Malik Khātūn va Hāfiz [Purpose of the wise: Jahān Malik Khātūn and Hāfiz] (Tehran: Gawhar, 1367/1987), 23. The second manuscript used by the editors of Jahān’s Dīvān is the Topkapi manuscript, which is catalogued MS H 867.24Malik Khātūn, Dīvān, x. As Brookshaw points out, this is the second-most complete manuscript, and Fehmi Karatay dates it to 1437.25Brookshaw, “Jahān-Malik Khātūn,” in Encyclopædia Iranica. The third manuscript, in Edward G. Browne’s collection, includes only 500 couplets, and bears the date 1028/1619. It is recorded in Reynold A. Nicholson’s catalogue on page 237 as Jahān’s Dīvān at the University of Cambridge.26Malik Khātūn, Dīvān, 237. Brookshaw cites Browne’s catalogue, but gives 1618 as the date. See Brookshaw, “Jahān-Malik Khātūn,” in Encyclopædia Iranica. In 1344/1966, the late Saʿīd Nafīsī published an article about Jahān that mentioned three manuscripts of her Dīvān: Supplément persan 736, Supplément persan 1102, and Browne’s manuscript. According to Nafīsī, manuscript 1102 included 1,300 couplets by Jahān.27Saʿīd Nafīsī, “Hāfiz-u Jahān-Malik Khātūn” [“Hāfiz and Jahān-Malik Khātūn”], in Majmūʿah-ʾi maqālāt darbārah-ʾi Hāfiz [Collection of articles on Hāfiz], ed. Akbar Khudāʹparast (Tehran: Hunar va Farhang: 1363/1984), 210–11. As the editors of Jahān’s Dīvān have not consulted Supplément persan 1102, this edition does not have all her extant poems.28Dawlatʹābādī, Manzūr-i khiradmand, 23–24.

Translations of Jahān Malik Khātūn’s Poetry

Several scholars have published translations of Jahān’s poetry.29A few of Jahān Malik Khātūn’s poems have also been translated into Indonesian and published online, an example of worldwide attention being paid to Jahān Malik Khātūn’s poetry. See “Tag: Jahan Malik Khatun,” in Bacapetra, https://www.bacapetra.co/tag/jahan-malik-khatun/. Among them, Dick Davis has published three books that include selections of her poems: Faces of Love: Hafez and the Poets of Shiraz (with seventy-two of her poems), The Mirror of My Heart: A Thousand Years of Persian Poetry by Women (with thirty-eight poems), and Pearls That Soak My Dress: Elegies for A Child (with twenty-four poems).30Davis, Faces of Love, The Mirror of My Heart, and Pearls that Soak My Dress: Elegies for a Child, trans. Dick Davis (Washington, DC: Mage Publishers, 2021). Rebecca Ruth Gould and Kayvan Tahmasebian have also translated several of her poems, including one of those discovered by Basharī in a 19th century manuscript of Jahān’s Dīvān, as noted above. This ghazal was probably written by Jahān, but mistakenly attributed to Amīr Khusraw Dihlavī (d. 725/1325).31Kayvan Tahmasebian and Rebecca Ruth Gould, “Your love weighs sweetly…: A Poem by Jahan Malek Khātūn,” The Margins, modified March 9, 2021, https://aaww.org/your-love-weighs-sweetly-a-poem-by-jahan-malek-khatun/ A few months after their first translation, Gould and Tahmasebian published another online article in which they translated three more of Jahān’s poems and part of the preface that she wrote to her collection of poetry. Concerning their method of translation, Gould and Tahmasebian explain that they ‘keep faith with the poeticity of the original rather than with any precise word or syntactic order,’32Rebecca Ruth Gould and Kayvan Tahmasebian, “Writing Poetry in 14th-Century Iran: Jahan Malek Khatun and Women’s Writings in the Islamic World,” Global Literary Theory, July 6, 2021. https://globallit.hcommons.org/2021/07/06/writing-poetry-in-14th-century-iran-jahan-malek-khatun-and-womens-writing-in-the-islamic-world/ and they call for attention to Jahān’s little-known ghazals. Their translations offer new and fascinating insights, particularly in terms of the poet’s gender. The authors suggest that her ghazals ‘mix witty sarcasm with provocative reflections on female desire.’33Gould and Tahmasebian, “Writing Poetry in 14th-Century Iran.”

Mediaeval Reception of Jahān Malik Khātūn

Information about Jahān’s literary career is as scarce as that concerning her personal life. Some of the information we have about her literary career can be inferred from poems written by her contemporaries, who were all eminent male poets. These works are worthy of close attention, because they were written either soon after her death, or while she was still alive. My aim in this article is to review and analyse Jahān’s contemporary reception, which will provide valuable insights into the life and career of Jahān as the only mediaeval female poet for whom we have a sizeable collection of poetry. Her reception has so far remained understudied, but it is an important source of information about her experience as a female author. The lines that Zākānī, the well-known poet and parodist, wrote about Jahān are particularly interesting. According to the literary scholar Muhammad Ishaque, Dawlatʹshāh’s Tazkirat al-shuʿarā’ mentions that Jahān frequently participated in poetic contests with Zākānī.34Muhammad Ishaque, Four Eminent Poetesses of Iran: With a Brief Survey of Iranian and Indian Poetesses of Neo-Persian (Calcutta: Ishaque Publication Fund Series-I, 1950), 65.

In his Javāhir al-ʿajāyib, Fakhrī Hiravī describes Jahān’s social status and her virtuous character. He records her as ‘beautiful and having access to all worldly means. In her majlis, she was always surrounded by witty and graceful boon companions whom she took care of. Jahān’s wit, graceful disposition and virtue of understanding were appreciated by the elite.’ Hiravī also recounts that when Zākānī moved to Shiraz from Qazvin, he learned about and participated in Jahān’s majlis, attended by such elite, witty, and graceful boon companions. Hiravī reports that on one occasion, a poetic contest between Jahān and Zākānī continued until late at night. They improvised poetry, debated, and exchanged witty remarks, and Jahān was deemed superior. The next time Zākānī intended to participate in another contest at Jahān’s house, he realised that she had been married to the vizier. On the spot, Zākānī composed a qitʿah ending with the following hemistich:

!خدای جهان را جهان تنگ نیست

By Jahān’s God (or by the world’s God), Jahān (or the world) is not tight.35The word tang has a wide range of meanings. Dihkhudā defines the word tang as the antonym of farākh, two meanings of which are loose and open. I have chosen these meanings because of their semantic relevance to the context of the pornographic lampoons about Jahān-Malik Khātūn. See “تنگ” and “فراخ,” in Dehkhoda lexicon. It is also worth mentioning that Steingass considers the word تنگ a frequent substitute for the word تنک, pronounced as /tanuk/ or /tunuk/, meaning slender, thin, weak, or delicate. When substituted by تنگ it can also mean effeminate. See Steingass, “تنک,” in A Comprehensive Persian-English Dictionary. The most relevant meanings of the word تنگ in Steingass are narrow, a strait, and also rare. See Steingass, A Comprehensive Persian-English Dictionary, s.v. تنگ. Steingass gives similar meanings for فراخ.

Zākānī managed to send this occasional poem to Jahān’s house. When the vizier read the poem, Jahān realised that Zākānī had used his wits in the composition. As Hiravī explains, Jahān and her husband then invited Zākānī to their house and duly received him.36Sultān Muhammad Fakhrī bin Muhammad Amīrī Hiravī, Tazkarih-yi rawwzat al-salātīn va javāhir al- ʿajāyib [The memoirs of garden of the kings and gems of the wonders], ed. Siyid Hisām al-Dīn Rāshidī (Karachi: Vafāʾī, 1968), 122.

As indicated in the translation, it is possible to interpret the line in two ways due to the pun on the word Jahān (lit. the world) and the semantic field of the adjective tang (lit. tight). Both of these interpretations are misogynistic, but the second one has a pornographic undertone. On the literal level, this hemistich means that the world is not a limited space, indicated by the word tang. As we know the recipient of this pun was Jahān’s husband, a man of power and status, this line can be interpreted as a sarcastic way of criticising him for choosing Jahān as his wife, as if the poet means, ‘You had the freedom to make much better choices as your world is not limited!’ The second possible reading of the line implies criticising Jahān’s husband for choosing her as his wife because her vagina was not tight, possibly alluding to the fact that she was not a virgin.

The association of women’s chastity and virtuosity to their virginity has a long enduring history. As Talattof points out, metaphorical references to a woman’s hymen, implying her virginity, appear frequently in classical Persian literature. Talattof gives examples such as dar-i ganj-khānah (door to the treasure house), durj-i qand (jewel box of sugar), kān-i laʿl (mine of rubies), and qufl-i zarrīn (golden lock) from the works of Nizāmī Ganjavī (d. 606/1209), which ‘generally portray women in a more progressive light.’ Translating a woman’s chastity into her virginity is also reflected in Persian contemporary literature.37Kamran Talattof, Modernity, Sexuality and Ideology in Iran: The Life and Legacy of Popular Iranian Female Artists (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2011), 36.

In her investigation of women’s social lives according to the Zoroastrian belief system, Katāyūn Mazdāpūr traces the roots of masculinist boundaries set for women to patriarchal Indo-European social norms. Mazdāpūr asserts that such social norms have been maintained and expanded within the Zoroastrian religion, which consists of the initial revelation to Zoroaster plus later rulings and interpretations by priests. According to these patriarchal norms, a chaste woman was expected to become engaged at the age of nine, marry at the age of twelve, start having sexual intercourse with her husband after her first menstruation, live in separation during her menstrual period, breast-feed her babies, remain loyal and obedient to her husband, willingly submit to his sexual desires, speak little, and be veiled (mastūr).38Katāyūn Mazdāpūr, “Zan dar āʾīn-i Zartushtī” [Woman in Zoroastrian rituals], in Hayāt-i ijtimāʿī-i zan dar tārīkh-i Īrān [Social life of woman in the history of Iran] (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1369/1990), 1:59–64, 67, 85, 87.

Mazdāpūr’s discussion shows that the boundaries set for women by these ancient socioreligious norms clearly connect women’s sexuality and reproductivity to ritualistic and shameful taboos that limit their social power, agency, and mobility. Leila Ahmed points out that women’s bodies and sexuality in Islamic societies of the Middle East have been associated with shame,39Leila Ahmed, Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 35–37. which Mazdāpūr asserts has existed for millennia before the advent of Islam in the Middle East. Perhaps it is crossing ancient patriarchal boundaries, defined by this shame, that elicits sexist remarks about women like Jahān. The line attributed to Zākānī therefore was probably meant to imply that Jahān was not a virgin, and hence a morally loose woman who was not worthy of being chosen for marriage. As explained below, the implications of this line might not be more than figurative references to Jahān’s breaking the patriarchal norms of composing poetry as an act of transgression. By writing poetry and attending court gatherings in the presence of male poets, she had transgressed the boundaries expected for chaste women, which meant being silent and bound to the private world behind curtains.40For an extensive discussion of ‘silence’ as a desired virtue for women and its implications for women’s authorship, see Farzaneh Milani, “Revealing and Concealing: Parvīn Iʿtisāmī” in Veils and Words: The Emerging Voices of Iranian Women Writers (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1992), 100–26.

A similar story appears in Dawlatshāh’s Tazkirat al-shuʿarā’, from which the complete qitʿah is taken:

وزیرا جهان قحبه ای بی وفاست

ترا زین چنین قحبه ای ننگ نیست[؟]

برو کس فراخی دگر را بخواه

خدای جهان را جهان تنگ نیست41Dawlatʹshāh, Tazkirat al-shuʿarāʾ, 289.

O Vizier, Jahān is an infidel whore:

Aren’t you ashamed of such a whore?

Go desire another loose cunt!

By Jahān’s God (or by the world’s God), Jahān (or the world) is not tight.42Translations are mine, unless otherwise stated. To remain as close as possible to the original, I translate Persian poems and texts literally.

The same lines also appear in Tazkirah-yi mirʾāt al-khayāl by Shīr ʿAlī Khān Lawdī, a Persian-speaking literary figure who lived in India in the seventeenth century. Reportedly, Zākānī wrote and sent these lines to Khājah Amīn al-Dīn, the influential vizier of Shāh Abū Ishāq, after Jahān was married to him.43Shīr ʿAlī Khān Lūdī, Tazkirah-ʾi mirʾāt al-khiyāl [Memoir of mirror of the phantom], ed. Hamīd Hasanī and Bihrūz Safarʹzādah (Tehran: Rawzanah, 1377/1998), 44–45.

Domenico Ingenito suggests a slightly different translation for these lines:

O Vizier, Jahān is an infidel whore:

Aren’t you ashamed of such a whore?

Discard her and choose another large cunt

Isn’t Jahān too tight for the lord of the world [jahān]?44Domenico Ingenito, “Jahān-Malik Khātūn: Gender, Canon and Persona in the Poems of a Premodern Persian Princess,” in The Beloved in Middle Eastern Literatures: The Culture of Love and Languishing, eds. Alireza Korangy, Hanadi al-Samman, and Michael Beard (London: I. B. Tauris, 2017), 202.

Ingenito suggests that Dawlatshāh might have mistakenly attributed these lines to Zākānī, because they do not appear in his Dīvān. While referring to a variation of the same quatrain in the poetry collection of Salmān Sāvujī (d. 778/1376), he proposes that probably the word Jahān in this variation refers to the world, and not to Jahān:

O Vizier, the world is an infidel whore

Aren’t you ashamed of such a whore?

Seek abundance outside of this one [i.e., the mundane world]

Isn’t the world too tight for the lord of the World?45Ingenito, “Jahān-Malik Khātūn,” 202–3. Ingenito cites Salmān Sāvujī, Kulliyāt [Canon], ed. ʿAlī ʿAbbās Vafāʾī (Tehran: Dānishgāh-i Tihrān, 1382/2003), 304.

Ingenito then suggests that if Sāvujī is referring to an unspecified vizier, and to the infidelity of the ephemeral world, then the version attributed to Zākānī might be his manipulation of the poem ‘to vituperate Princess Jahān with obscene language.’46Ingenito, “Jahān-Malik Khātūn,” 203. Ingenito has taken the lines that make an impersonal reading of the poem possible from Sāvujī’s Dīvān, edited by ʿAlī ʿAbbās Vafāʾī. Although his reading and argument are plausible concerning the version he refers to, another edition of Sāvujī’s collection of poetry quotes these lines as follows:

وزیرا جهان قحبه ای بی وفاست

ترا زین چنین قحبه ای ننگ نیست[؟]

برو ته فراخی دگر را بخواه

خدای جهان را جهان تنگ نیست47Sāvujī, Dīvān, 559.

O Vizier, Jahān is an infidel whore:

Aren’t you ashamed of such a whore?

Go desire another loose ass!

By Jahān’s God (or by the world’s God), Jahān (or the world) is not tight.

This version is almost the same as the version attributed to Zākānī, with the only difference being the body parts to which these two poems refer. It is difficult to ascertain which version may be the original, or even which one was written by Sāvujī or Zākānī. What matters is how Jahān’s reputation was scrutinised by her contemporaries. Analysing these remarks made by the ‘elite’ men of letters, at least one of whom was supported by the court of Jahān’s royal dynasty, sheds light on the experience of Jahān as a major female poet and the challenges she faced.

Fakhrī Hiravī’s anecdote about Zākānī’s qitʿah, if taken as historically accurate, is the only account reflecting Jahān’s response to her contemporary reception. This account includes only the last hemistich of the piece. If we assume that Hiravī is talking about the same poem attributed to Zākānī in Lawdī’s anthology, and if he has not whitewashed the obscenity of the poem, then his anecdote becomes a complicated puzzle. It portrays Jahān’s response to this poem and her relationship with Zākānī as amicable and playful. In his book on Jahān, Dawlatʹābādī mentions that satirical remarks such as those Zākānī wrote about Jahān, or the satirical exchanges between Zākānī and Salmān Sāvujī, are examples of a common tradition of that era.48Dawlatʹābādī, Manzūr-i khiradmand, 6. Ricardo Zipoli similarly claims that women’s sexual desire is the main target for satire in Persian poetry, citing lines from eminent poets such as Rūdakī (d. 328/940), Anvarī (d. ca. 564–65/1169–70) and Khāqānī (d. between 582–83/1186-87 and 595/1199) in which women’s sexual desires and erotic activities are associated with easy virtue.49Riccardo Zipoli, Irreverent Persia (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2015), 108–12. In the case of Jahān, it is not easy to clarify whether the misogyny in Zākānī’s poem was tolerated because it was normal in mediaeval times, or if it was cherished as a witty play on words on a merry occasion, such as a wedding. What is clear, however, is that Zākānī’s lines about Jahān can be considered pornographic; however, such a reading remained uncriticized for centuries.

Analysing the misogynistic or pornographic reception of female poets is one way to break the ill cycle of such remarks. The modern responses to the tradition that slandered Jahān, however, have remained mild and forgiving. For instance, Ishāque referred to these poems as ‘very coarse verses,’50Ishaque, Four Eminent Poetesses of Iran, 65. while Safā considered the anecdotes about Zākānī’s poems on Jahān’s marriage humorous.51Safā, Tarīkh-i adabiyyāt dar Iran, 3:1048. Nafīsī dismissed reports of Jahān having been lampooned by Zākānī, as he believed these accusations to be baseless.52Nafīsī, “Hāfiz va Jahān-Malik Khātūn,” 211. More than six hundred years ago, Jahān transgressed the limits her society placed on women with her poetry. It is time to break down such ubiquitous norms meticulously to decode reactions from male contemporaries of a successful, but ostracised, female poet like Jahān. The pieces of poetry attributed to Zākānī, or other male poets, discussed here are specimens that demonstrate mediaeval patriarchal gender norms with millennia-old roots. This analysis may inevitably involve the projection of modern understandings of gender norms onto those in effect in the mediaeval era. Nevertheless, reading Jahān’s contemporary reception analytically is a preliminary step toward understanding the legacy of this mediaeval Persian female poet.

*This article is part of the ERC-Advanced Grant project entitled Beyond Sharia: The Role of Sufism in Shaping Islam, which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101020403).