“Fakhr Uzma Arghun: Poet, Journalist, and Advocate for Women in Modern Iran”

Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn (1277-1345/1898-1966) was a pioneering poet, journalist, and activist dedicated to advancing the status of women and expanding their roles in society. Her work focused primarily on the socio-political progress of Iran, with a particular emphasis on improving the lives of Iranian women. For many years, Fakhr ꜥUzmā was an active member of both the Jamꜥīyyat-i Nisvān-i Vatanʹkhvāh-i Īrān (The Society of Iranian Patriotic Women) and the Kānūn-i Bānuvān (Women’s Association). In addition to her work with civil institutions, she was a committed activist. She founded a girls’ school and worked tirelessly to sustain it despite financial hardship.1Sīmīn Bihbahānī, who was Fakhr ʿUzmā’s first child, frequently refers to her mother’s financial difficulties. Fakhr ʿUzmā, the daughter of Mukarram al-Sultān, had lived in comfort for many years. However, after her father’s death, little remained for her and her two brothers, and she was left with nothing from the luxury and comforts of her youth. She and her second husband spent all their money on the newspaper they were running, despite having no income. She had sold all her jewelry and used the proceeds to cover the cost of paper and printing. The newspaper was called Āyandah-ʾi Īrān, with Fakhr ʿUzmā serving as its editor and her husband as its manager. See Sīmīn Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh [With my mother] (Tehran: Sukhan, 1390/2011), 34. She contributed articles to several newspapers, including ꜥĀlam-i Nisvān, Jamꜥīyyat-i Nisvān-i Vatanʹkhvāh-i Īrān, Āyandah-ʾi Īrān, Nāmah-ʾi Bānuvān–i Īrān, and Āzādī-i Khalq, and also served as the editorin-chief for the latter three.

Fakhr ꜥUzmā’s poetry and prose served her social and political goals, with her poetry earned the admiration of prominent contemporaries such as Malik al-Shuʿarā Bahār, and she hosted weekly gatherings that fostered dialogue among poets. Her extant poems, which establish her as a moderate modernist, reflect her deep engagement with social issues. Although she embraced innovation in both the content and form of her poetry, she retained a classical language and adhered to traditional aesthetic standards. Fakhr ꜥUzmā employed two modern forms in her poetry, which are examined in this article. Her most significant innovations, in both content and form, are evident in her exploration of themes such as the importance of acquiring knowledge, the hijab, women’s rights, politics, and patriotism. However, in the realm of romantic poetry, she made no significant innovations.

Fakhr ꜥUzmā was married twice. Her first marriage resulted in the birth of Sīmīnbar Khalīlī (later known as Sīmīn Bihbahānī). She raised her daughter to become a poet, thereby shaping the direction of her career. From her second marriage, she had five children. In 1337/1958, Fakhr ꜥUzmā traveled to the United States to care for her youngest son, where she died eight years later. According to her wishes, Fakhr ʿUzmā’s body was brought back to Iran and buried in the tomb of Ibn Bābavayh, where her father, a descendant of Shaykh Sadūq (Ibn Bābavayh), and her mother were also buried.

Review of Previous Scholarship

The life of Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn has been briefly mentioned in Several works, usually in only a few pages, which generally provide biographical information and cite some of her poems, though they often contain historical inaccuracies, most notably regarding her year of birth. Sukhanvarān-i nāmī-i muʿāsir-i Īrān (Famous poets of contemporary Iran) incorrectly lists her birth year as 1279/1900.2Muhammad-Bāqir Burqaꜥī, Sukhanvarān-i nāmī-i muʿāsir-i Īrān [Famous poets of contemporary Iran] (Tehran: Khurram, 1373/1994), 2593. Her birth year is given as 1278/1899 in both Zanān-i rūzʹnāmahʹnigār va andīshmand-i Īrānī (Iranian women journalists and intellectuals) and the article “Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn; mādar-i shāʿir va rūzʹnāmahʹnigār-i Sīmīn Bihbahānī” (Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn: The poet and journalist mother of Sīmīn Bihbahānī), both of which are incorrect.3Parī Shaykh al-Islāmī, Zanān-i rūzʹnāmahʹnigār va andīshmand-i Īrānī [Iranian women journalists and intellectuals] (Tehran: Zarrīn, 1351/1972), 158; Nāsir al-Dīn Parvīn, “Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, Mādar-i shāʿir va rūzʹnāmahʹnigār-i Sīmīn Bihbahānī” [Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn: The poet and journalist mother of Sīmīn Bihbahānī], Bukhārā 101 (Murdād–Shahrīvar 1393/August–September 2014): 139. In an interview with Parvīn magazine, Sīmīn Bihbahānī refers to her mother’s birth year as 1272/1893, which is r also incorrect.4Sīmīn Bihbahānī, “Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn dar guftugū bā dukhtarash (Sīmīn Bihbahānī)” [Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn in conversation with her daughter (Sīmīn Bihbahānī)], Parvīn 12 (Urdībihisht 1382/April 2003): 25. However, Fakhr ꜥUzmā’s birth year, as recorded on both her diploma and gravestone, is listed as 1277/1898, which can be considered the most reliable source.5In a conversation with Ātifah Bihbahānī, the wife of the late Sīmīn Bihbahānī’s son, she mentioned that the year 1277/1898 is recorded as the birth year of Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn on her diploma. However, she did not agree to the public release of a photograph of the diploma. Furthermore, most sources mention her year of death as 1345/1966, except for Nīmahʹhā-yi nātamām (Incomplete halves), which incorrectly reports it as 1342/1963.6Pūrān Farrukhzād, Nīmahʹhā-yi nātamām [Incomplete halves] (Tehran: Kitābʹsarā-yi Tandīs, 1380/2001), 167.

In some sources, it is mistakenly claimed that Fakhr ʿUzmā had three children with her second husband, ʿĀdil Khalꜥatbarī, namely, ʿĀdilʹnizhād, ʿĀdilʹdukht, and ʿĀdilʹfar.7Rūhangīz Karāchī, Andīshahʹnigārān-i zan dar shiꜥr-i Mashrūtah [Women thinkers in Constitutional poetry] (Tehran: Dānishgāh-i al-Zahrā, 1381/2002), 117; Farrukhzād, Nīmahʹhā-yi nātamām, 167; Fakhrī Qavīmī, Kārʹnāmah-ʾi zanān-i mashhūr-i Īrān: Az qabl az Islām tā ʿasr-i hāzir [Achievements of famous Iranian women: From the pre-Islamic period till today] (Tehran: Vizārat-i Āmūzish va Parvarish, 1352/1973), 119; Banafshah Hijāzī, Tazkirah-ʾi andarūnī: Sharh-i ahvāl va shiʿr-i shāʿirān-i zan dar ʿasr-i Qājār tā Pahlavī [A biographical anthology of the women’s quarters: Biography and poetry of women poets in the Qajar and Pahlavi eras] (Tehran: Qasīdahʹsarā, 1382/2003), 152; Parvīn, “Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn,” 140. In reality, they had five children, two of whom—ꜥĀdilʹpūr and ꜥĀdilʹbānū—died in childhood.8Sīmīn Bihbahānī composed a poem upon the death of ʿĀdilʹpūr:

“O seven-year-old child, O ʿĀdilʹpūr,

Who, by a farmer’s mistake, became one of the living dead.

Arise and see how, from your sorrow,

The just one [ʿĀdil] is saddened, and the pride of justice [Fakhr ʿĀdil] is in pain.” See Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 289. There are some other minor inaccuracies that are mentioned in some of these sources.9Kārʹnāmah-ʾi zanān-i mashhūr-i Īrān incorrectly states that fakhr spent her childhood and early education in Switzerland. See Qavīmī, Kārʹnāmah-ʾi zanān-i mashhūr-i Īrān, 118. In fact, she never visited the country. The book likely confuses this with the fact that her father hired a Swiss tutor to teach French to her and her two siblings at home.

Zanān-i rūzʹnāmahʹnigār va andīshmand-i Īrānī claims that Fakhr ʿUzmā earned a diploma in French from the Institut Franco-Persan and then studied English at the American School. See Shaykh al-Islāmī, Zanān-i rūzʹnāmahʹnigār va andīshmand-i Īrānī, 159. In reality, she attended the Jeanne d’Arc School in Tehran, where she obtained her secondary education diploma in French within a short period. See Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 38. She also received a separate diploma from the American School. See Bihbahānī, “Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn dar guftugū bā dukhtarash (Sīmīn Bihbahānī),” 24.

On the other hand, Sīmīn Bihbahānī has several autobiographical writings. However, only in Bā mādar-am hamrāh she offers the most comprehensive and independent account of her mother’s life.

This article examines the modernist elements of Fakhr ʿUzmā’s poetry by analyzing her works and illustrating the innovations she brought to both form and content.

Life and Activities

Fakhr ꜥUzmā was born in 1277/1898. Originally named Fakhr al-Tāj, she received the title Fakhr ʿUzmā after Ahmad Shah Qājār’s marriage proposal.10Bihbahānī, “Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn dar guftugū bā dukhtarash (Sīmīn Bihbahānī),” 24–25. Her mother, ꜥAzamat al-Saltanah, was the granddaughter of Hidāyat Khān Rāshtī, whose lineage traced back to the Gīlān-Shāhān dynasty, with their ancestor being Qābūs Vushmagīr, the Ziyarid ruler of Gorgan and Tabaristan in the 4th century AH/10th–11th centuries. During her childhood, Fakhr ʿUzmā lost her mother to the plague. Her father, Murtazā Qulī Khān Mukarram al-Saltanah Arghūn, a wealthy man and a commander of a tūmān (military unit).11Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 10, 75.

Fakhr ʿUzmā was born into a family that prioritized the education of both daughters and sons. Her father ensured that she and her two brothers received the best possible education. Years later, Fakhr ʿUzmā referenced this in one of her poems: “Fakhrī, take pride in the fact that, from the very beginning / you have stood at the gateway to the mansion of knowledge.”12Fakhr ꜥUzmā Arghūn, “Kujā būdam, dar kujā hastam!” [Where was I? Where am I?], ꜥĀlam-i Nisvān 4, no. 1 (Sunbulah 1302/September 1923): 40.

Her family operated a private school staffed by two teachers. Āqā Shaykh-Kāzim Yazdī, who taught fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), usūl (principles of jurisprudence), Quran, and Arabic; and Mīrzā Tālib Khān Bahr al-ꜥUlūm, who taught Physics, Chemistry, and Mathematics. Fakhr ʿUzmā began attending this school at the age of three, although she herself claims that she did not comprehend much until she was five. However, over time, she demonstrated remarkable ability, to the extent that Mīrzā Tālib Khān once declared that she was more intelligent than her brothers and that, in fact, she was his best student.

It seems that Fakhr ʿUzmā wrote the serialized, unfinished novel Sarʹguzasht-i yak zan (The story of a woman) based on the memories of this private school and the influence her father had on her life. The novel is narrated in the first person, with a woman recounting her childhood to the audience. She recalls that when she was three years old, a cleric served as her home tutor. However, due to her young age, she found this cleric very ugly and was afraid of him. The narrator criticizes the educational practices of the time, which involved scaring and physically punishing children, enrolling students at a young age, and restricting play. She compares these practices with those of civilized countries, where children learn the alphabet through play. She identifies these issues as significant factors contributing to Iran’s lack of progress compared to other nations. Additionally, she criticizes the absence of kindergartens in Iran and argues that children should begin their literacy education at an appropriate age — namely, at seven years old. A notable aspect of the narrative is the narrator’s assertion that her father loved her more than his sons, describing her as the “crown jewel” of the family. Given that most of the core data in this novel matches the real details of Fakhri’s life—such as the father’s military background in the story, the existence of a private school, and being beaten by the home tutor13Fakhri’s father held the rank of Amir-Tuman, and in the novel as well it is mentioned that the father is a military man: “His habit was that he would first go into his own room, take off his military coat, gloves, and helmet.”

Fakhr ꜥUzmā Arghūn, “Sarʹguzasht-i yak zan” [The story of a woman], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 3, no. 3 (1311/1932): 4.

The private school is also described in the novel as follows: “This school consisted of one of the upper rooms of our house, which was considered part of the biruni section.” Fakhr ꜥUzmā Arghūn, “Sarʹguzasht-i yak zan” [The story of a woman], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 3, no. 4 (1311/1932): 4.

The narrator also recounts that at one point she was beaten by the mentioned home tutor:

“The Mullah raised the switch and struck my back several times, saying: ‘You accursed wretch! How is it that you know how to trick your way out of coming to the school, but you don’t know your lesson?” Fakhr ꜥUzmā Arghūn, “Sarʹguzasht-i yak zan” [The story of a woman], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 4, no. 5-6 (1311/1932): 7. In real life as well, Fakhri was beaten by Agha Sheikh Kazem: “Fakhri recalled the day when {her mistake in reading the Qur’an} brought upon her a blow from the switch—a pain she remembered every time she looked at the Qur’an.”Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh,28.

For her serialized fiction see, Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Sarʹguzasht-i yak zan,” Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 3, nos. 2–5 (1311/1932); 4, nos. 6–5, 11–12, 15–16, 21–22 (1312/1933).—it is likely that the father’s greater affection for his daughter in the novel also reflects reality.

Mukarram al-Sultān hired a Swiss teacher named Madame Meuron, and this woman, along with her husband, moved into their house to teach French to his children. After mastering French, Fakhr ʿUzmā attended the Jeanne d’Arc School and earned her diploma in a short time. She also learned to play the tār, and her music instructor was a Jewish woman named Jan Mashaq. After learning seven musical modes, Fakhr ʿUzmā became a student of ʿAbd Allāh Khān Dudāngah, who would sit in a neighboring room, singing the tasnīfs and gūshahs14Tasnīf: A composed vocal piece combining melody and metered poetry, expressing a specific idea or message. This form is also referred to as a Tarāneh (song). Also, gūshah is a smaller melodic piece within a Dastgāh or its related Avāzes. Each Dastgāh or āvāz is made up of several gūshahs. A gūshah is not further subdivided and usually spans only a few notes. See Aref Taravati, Farhang-i Mūsiqi-i Irani, [Encyclopedia of Iranian Music] (Tehran: Kanūn-i Chang,1360 /1981), 26, 105., while Fakhr ʿUzmā played them on the tār. If she made a mistake, the instructor would correct her from the other room.15Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 6, 37–38. In 1296/1917, when Fakhr ʿUzmā was only nineteen years old, she composed a tasnīf, and ʿAbd Allāh Khān set it to music in the Sigāh16Sigāh: one of the seven principal modes of Persian music. It was also the name of an old scale within the Rast-Panjgāh system. It has also appeared as Sigāh and is considered one of the 24 musical shu‘behs (sub-modes) discussed in early treatises. See Taravati, Farhang-i Mūsiqi-i Irani, 68. ode.

“Why did you let your tangled hair fall so carelessly on your face?

Why did you scatter a heart as vast as the world?

With a sweet smile, from those lips like rubies,

You made me taste the sweetness of sugar and cast a frenzy into my heart.

When I tried to grasp your hem, my dear, my hand failed.

There is no cure but death, for I long for you endlessly.”17Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 39.

Fakhr ʿUzmā was an admirer of the Iqdām newspaper and a supporter of its editor-in-chief, ꜥAbbās Khalīlī. In 1302/1923, the newspaper published one of her poems for the first time:

“The kingdom must be made crimson with the blood of the traitor,

A river of blood must flow from every corner of the land.

If you seek the grandeur and glory of kings, like Kāvah,

You must free the kingdom of Jam from the lowly tyrant Zahhāk.

Fakhriyā! Do not think of reforming this ruin except through blood,

A flood of blood must flow over the impurities.

Do not mourn what is past, for it is beyond reach,

Now focus on the reforms in the future.”18Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Saylʹāb-i khūn,” Iqdām 2, no. 133 (1341/1922): 2.

This poem was composed during the final years of Ahmad Shah Qajar’s reign, amid the turbulent political and social conditions of the era. Its content may seem extreme and violent by contemporary standards; however, during those years, when the constitutionalist cause had been suppressed, similar poems frequently appeared in the press. After reading the poem, ʿAbbās Khalīlī became eager to meet its young poetess. Bihbahānī recounts this encounter: “Khalīlī immediately ordered the poem to be printed, and in his imagination, he envisioned the face of a revolutionary girl who, like the poets of the Constitutional era, called for the shedding of traitors’ blood. He became madly in love with her.”19Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 18. Later, ʿAbbās Khalīlī sent his relatives to propose to Mukarram al-Sultān. After their marriage, they lived together for only fifteen days, after which ʿAbbās Khalīlī was exiled to Kirmānshāh by the order of Rizā Khān Sardār Sipah. During his two years of exile, he had no contact with Fakhr ʿUzmā and could only send messages to her once or twice a month through an intermediary.

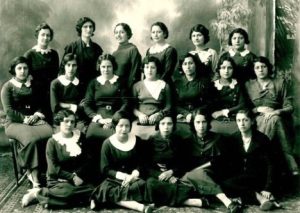

In the absence of her husband, Fakhr ʿUzmā decided to collaborate with her friends from before her marriage to improve the social status of Iranian women. A few years earlier, in early Bahman 1301/January 1923, Muhtaram Iskandarī had invited a group of enlightened women from Tehran to oversee the students’ exams at the school she managed. After the exams, Iskandarī delivered a speech on the necessity of advancing the cause of Iranian women. The women present at the meeting welcomed Iskandarī’s remarks, and the solidarity that emerged during the meeting on Bahman 10, 1301/January 30, 1923, led to the establishment of the Jamʿīyyat-i Nisvān-i Vatanʹkhvāh-i Īrān. This society was active from 1301/1922 to 1314/1935, until Rizā Shah issued a decree for its dissolution.

In the Jamʿīyyat-i Nisvān-i Vatanʹkhvāh-i Īrān, the members initially decided to establish a school for illiterate women. Education in this school was organized around a skill-exchange system. Women who gained literacy could, in turn, teach other practical crafts such as weaving or sewing. The society also organized weekly lecture sessions, inviting figures such as Malik al-Shuꜥarā Bahār, Saꜥīd Nafīsī, Rashīd Yāsamī, Nizām Vafā, and Amīr Jāhid to deliver lectures for the women. The society generated income from various sources, including donations of women’s artwork—such as embroidery and painting—or the sale of jewelry by many women to support the development of the school.20Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 66–69. According to the society’s reports, Fakhr ʿUzmā was responsible for overseeing the management of the Madrasah-ʾi Akābir (School of the illiterate elders) within the society.21Muhammad Hussayn Khusrawʹpanāh, Jamʿīyyat-i Nisvān-i Vatanʹkhvāh-i Īrān [The society of Iranian patriotic women] (Tehran: Khujastah, 1400/2021), 40–41. Additionally, the Jamʿīyyat-i Nisvān-i Vatanʹkhvāh-i Īrānissued membership cards to its members, which featured a poem by Fakhr ʿUzmā at the top:

“For your own rights, strive, O woman,

And adorn yourself with purity and honor.

With knowledge and art, beautify your being,

So that a noble man may be nurtured in your lap.”

Although the membership card did not mention the poet’s name, this poem, along with the name of its poet, Fakhr ʿUzmā, was published in one of the issues of Āyandah-ʾi Īrān.22Fakhr ꜥUzmā Arghūn, “Ay Zan!” [O, woman], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 1, no. 24 (1309/1930): 1.

The society irregularly published a journal under its own name, from 1302–1305/1923–1926. The Jamʿīyyat-i Nisvān-i Vatanʹkhvāh-i Īrān journal continued until Bahman 1305/February 1927, after which it was permanently discontinued. According to the society’s board of directors, the irregular publication and eventual discontinuation of the journal were due to financial difficulties.23Khusrawʹpanāh, Jamʿīyyat-i Nisvān-i Vatanʹkhvāh-i Īrān, 48. From what remains of the journal’s archive, only one short story by Fakhr ʿUzmā, titled Adabiyāt (Literature), has been preserved. In this story, the author critiques the discrimination between male and female children. This story is about a woman who’s holding her newborn son and feeling happy and thankful that he’s a boy. But out of nowhere, an angel shows up and scolds her for feeling this way. The angel then shows her women from all around the world and explains that Iranian women also have potential and talent, just like anyone else, but they’re overlooked in society. The author points the finger at both men and women for the lack of progress of Iranian women and argues that a woman’s lap is the first school a child ever has.24Fakhr ꜥUzmā Arghūn, “Adabiyāt,” Jamʿīyyat-i Nisvān-i Vatanʹkhvāh-i Īrān 3, no. 11 (Bahman 1, 1305/January 21, 1927): 29–35.

Meanwhile, Fakhr ʿUzmā sent a poetic letter to Rizā Khān Sardār Sipah, urging the release of her husband. A brief response soon followed, instructing the release of ꜥAbbās Khalīlī. Fakhr ʿUzmā’s compelling prose proved valuable once again when she sent another letter to the then Rizā Shah, securing the release of her younger brother from prison.25Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 159–61. Eventually, Khalīlī returned from exile, though he had changed significantly. He had become impatient and difficult, and his affection for his wife had diminished. During his exile, he wrote the novel Ruzigār-i siyāh (Dark times), which addressed the deplorable condition of women. After reading the novel, Fakhr ꜥUzmā began to suspect that her husband had relationships with women of questionable background during his exile, based on his descriptions of their lives in the book. ꜥAbbās Khalīlī began hosting many parties, and among his guests were women whom he entertained privately in his room. One of the servants told Fakhr ʿUzmā about these visits and one day took her to his room to prove she had not lied about her husband. When Fakhr ʿUzmā entered the room and saw her husband, she told the servants and nurse to pack their things and got ready to go to her father’s house.26Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 54, 59. Although she was pregnant, she went back to her father’s home, where Mukarram al-Sultān welcomed her and supported her decision to leave her husband. In 1306/1927, Fakhr ʿUzmā gave birth to her first child, Sīmīnbar Khalīlī (Sīmīn Bihbahānī). Immediately after childbirth, she became even more dedicated to the work of the Jamʿīyyat-i Nisvān.27Fakhr ꜥUzmā’s increased motivation to work for the women’s cause becomes evident after her second separation. When she learns that her second husband, ꜥĀdil Khalꜥatbarī, has secretly remarried, she immediately kicks him out of the house that very night. The next day, without hesitation, she joins the Democratic Party at the invitation of Qavām al-Saltanah and takes on the role of advocating for women’s rights. See Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 452–53.

In the meantime, Fakhr ʿUzmā met two men she considered for marriage, but neither match happened for different reasons. In the first case, Fakhr ʿUzmā went to an Armenian doctor named Kāru about her daughter’s illness. The illness continued, and Fakhr ʿUzmā had to visit his office often. During these visits, they grew interested in each other. However, the problem was that they had different religions. Fakhr ʿUzmā, devoted to her Muslim faith, reluctantly turned down the Armenian doctor’s proposal. However, she was upset by the discrimination against Muslim women, wondering why a Muslim man could marry a non-Muslim woman, but a Muslim woman could not do the same. The second man Fakhr ʿUzmā considered marrying was her cousin, Sultān Hamīd Khān, who had just returned from Europe. Although Fakhr ʿUzmā did not love him, the marriage seemed reasonable to her. However, Sultān Hamīd Khān died shortly thereafter from leukemia, and no lasting bond developed between them.28Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 119–26, 130–36.

Finally, Fakhr ʿUzmā married a journalist named Jamāl al-Dīn Khalꜥatbarī in her second marriage.29It’s unclear how Fakhr ꜥUzmā met her second husband, but her family strongly opposed the marriage. Her younger brother, Abū Turāb Khān, was so opposed to the marriage that he actually made her write a letter before the wedding. In it, she had to say that it was her decision to go through with it and that she’d take on all the responsibility if anything went wrong. See Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 173–74; Fakhr ꜥUzmā’s second husband, Jamāl al-Dīn Khalꜥatbarī, had a title of ꜥĀdil al-Sultān. He added “ꜥĀdil” to his last name and changed Fakhr ꜥUzmā’s family name to his own. Thus, Fakhr ꜥUzmā referred to herself as Fakhr ꜥĀdil Khalꜥatbarī in her writings. The name “ꜥĀdil” was also added to their children’s names, like ꜥĀdilʹdukht (daughter), ꜥĀdilʹfar (son), and others. He was the editor of the newspaper Āyandah-ʾi Īrān, which started on Murdād 7, 1309/July 29, 1930.30Nāsir al-Dīn Parvīn, regarding Āyandah-ʾi Īrān, writes: “The rights to this publication were first given to Mīrzā Jaꜥfar Sharīꜥatʹmadār Khalꜥatbarī Tunikābunī, under the title Dīnʹdānāʾī (Religion of knowledge). However, it’s unclear how the rights were later transferred to Jamāl al-Dīn Khalꜥatbarī before the publication actually came out.” See Parvīn, “Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn,” 140. There are two key points here: First, Jamāl al-Dīn Khalꜥatbarī was from Tunikābun, and second, Sīmīn Bihbahānī mentions several times that Jamāl al-Dīn’s paternal grandfather was referred to as “Āqā-yi Sharīꜥatʹmādar.” See Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 224–25. So, it can be said that the person Nāsir al-Dīn Parvīn refers to as Mīrzā Jaꜥfar Sharīꜥatʹmadār Khalꜥatbarī Tunikābunī was actually Khalꜥatbarī’s father, who passed the newspaper rights on to his son. The first work Fakhr ʿUzmā published in Āyandah-ʾi Īrān was the poem “ꜥIllat-i kūtāh nimūdan-i zulf” (The reason for cutting hair short), which appeared under her name.31Fakhr ꜥUzmā Arghūn, “ꜥIllat-i kūtāh nimūdan-i zulf” [The reason for cutting hair short], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 1, no. 26 (1309/1930): 2. However, starting with issue 37 of the second year (1310/1931) of Āyandah-ʾi Īrān, her works were published under the name Fakhr ꜥĀdil Khalꜥatbarī. In the newspaper’s third year, she became the editor-in-chief and redefined its editorial direction. Previously a national, social, political, literary, and humorous publication, she transformed it into a political, social, literary, and pro-women platform, starting with issue 22 of the third year (Farvardīn 26, 1312/April 15, 1933).32Parvīn, “Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn,” 140. Many of Fakhr ʿUzmā’s modernist poems were published in this newspaper. In addition to publishing her own poetry, she sought to encourage other women to write by organizing poetry competitions. These efforts were all directed toward establishing a platform for women’s voices in the press.33Fakhr ʿUzmā would regularly publish her ghazals in different issues of Āyandah-ʾi Īrān and encourage women to respond to them. She also offered prizes for the best poem, such as a one-year free subscription to the newspaper or a book. She would specifically emphasize that these contests were for women only: “We kindly ask that respectable gentlemen do not take part in Āyandah-ʾi Īrān’s contest under false pretenses and allow the creativity of women to be tested. See Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Avvalīn musābaqah-ʾi zanānah barāyi āzmāyish-i tabꜥ-i bānuvān-i fāzalah” [The first women’s contest to test the talent of virtuous women], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 1, no. 25 (1309/1930): 3. For examples of these literary contests, see Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Gul-i subh” [The morning flower], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 3, no. 2 (1311/1932): 4; Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Shād zī chāmah-ʾi Nawrūzī bih Pārsī-i sarah” [Live joyfully, a New Year’s hymn in pure Persian], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 3, no. 21 (1312/1933): 4.

In the middle of 1311/1932, members of the Eastern Women’s Congress decided to hold their second congress in Tehran. The Jamꜥīyyat-i Nisvān-i Vatanʹkhvāh-i Īrān, tasked by the government, took charge of organizing the congress and the speeches. Fakhr ʿUzmā delivered four speeches at the Second Eastern Women’s Congress and hosted congress members in her home on one occasion. Her speeches covered topics such as women’s rights, the role of women in society, and the benefits of enrolling children in kindergarten.34Fakhr ʿUzmā’s first public speech, delivered on the topic of women’s rights, took place on Tuesday, Ābān 17, 1311/November 7, 1932. Her second speech occurred at a gathering where Fakhr ʿUzmā, together with ꜥĀdil Khalꜥatbarī, invited and welcomed the members of the Congress. In her speech, Fakhr ʿUzmā begins by praising Rizā Shah, stating: “Before the rise of the glorious sun of the reign of His Imperial Majesty, the all-powerful Shāhanshāh Pahlavī, may our souls be sacrificed for him, no progress or movement in the pursuit of women’s rights had been made in this land […] I humbly ask for permission to offer a few words on the topic of “women and life,” despite my limited ability. These two words hold great significance, and it can be said that they represent the essence of a woman’s life.” She then discusses the all-encompassing responsibility of women in life: “The source of both happiness and misery is the woman […] Life is like a flourishing garden, and the woman is its gardener. With her capable hands, she can remove the thorns and brushwood—symbolizing the difficulties of life—surrounding it.” Another speech by Fakhr ʿUzmā took place at the Eastern Women’s Congress at the first Iranian kindergarten, located on SafīꜥAlī Shah Street. In her speech, she discussed the benefits of enrolling children in kindergarten: “Dear ladies, the kindergarten will assist you in raising your beloved children until the age of seven, after which the school will take responsibility.” See Afsānah Najmābādī, Ghulamʹrizā Salāmī, Nahzat-i nisvān-i sharq [The Eastern women’s movement] (Tehran: Shīrāzah, 1389/2010), 6, 20–22, 197.

Regarding Fakhr ʿUzmā’s speech at her home for the Eastern Women’s Congress held in Tehran, there is no reference to it in the book Jamꜥīyyat-i Nisvān-i Vatanʹkhvāh-i Īrān [The Society of Iranian Patriotic Women] or Nahzat-i nisvān-i sharq [The Eastern women’s movement]. We do not have access to the full text of this speech. Sīmīn Bihbahānī also says nothing about the content of Fakhr ʿUzmā’s speech, except recalling “a night when female representatives from several Arab countries, including Syria and Lebanon, came to Iran for a discussion on women’s rights. At our home, they sat and talked with my mother and several other Iranian women […] My mother stood behind a tall desk with an oil lamp on it. She spoke in Arabic and French. After her, other women took their turn to speak.” See Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 238.

In 1314/1935, Rizā Shah issued an order to dissolve the Jamꜥīyyat-i Nisvān-i Vatanʹkhvāh-i Īrān. After more than a decade of activity, Fakhr ꜥUzmā temporarily left her position as a teacher and took on the role of Deputy Director of Women’s Education at the Ministry of Culture. She became the first woman in Iran to hold a senior administrative position. Additionally, she chose to convert part of her large home into a school for girls, establishing an institution that offered both elementary and secondary education. After some time, she invited a lawyer to visit the school weekly to deliver lectures to the students. The lawyer highlighted gaps in women’s legal rights, advising students on which clauses to include in their marriage contracts to protect themselves and which to avoid preventing problems. In addition, the students had to read their own work or that of other authors each week at the school’s literary society. Once a month, a play, written and performed by the students, was staged at the school.35Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 281–82, 375–76. Fakhr ʿUzmā also established vocational classes at the Women’s High School. This vocational section was intended to help women become financially independent in the future: “In specialized courses in home economics, nursing, the principles of motherhood, cooking, table setting, confectionery, handicrafts, sewing and tailoring, embroidery, millinery, painting, music, accounting, and office work, instruction is provided by experienced teachers.”36Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “be yāri-i khodā va nirou-ʾi dānesh” [With God’s Help and the Power of Knowledge], Nāmah-ʾi Bānuvān 3, no. 8 (1319/1940): 10.

She also emphasizes the necessity of women’s labor in her poetry:

“Women must all work / With knowledge and action, they must awaken society.”37Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Sa’y va Koushesh” [Hard Work and Effort], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 5, no. 5 (1313/1934): 4.

The girls’ high school was financially difficult for Fakhr ʿUzmā, as it did not earn enough income. Despite this, she remained determined to keep it running. Ultimately, in 1324/1945, she decided to close the school because of difficulty finding a suitable location for the classes and her declining health.

Following the dissolution of the Jamꜥīyyat-i Nisvān, many of its active members joined the Kānūn-i Bānuvān (The Women’s Association). The Kānūn was established on Urdībihisht 22, 1314/May 12, 1935 by order of Rizā Shah. Most of its founding members were women from the cultural and intellectual parts of society.38Maryam Fathī, Kānūn-i Bānuvān bā rūyʹkardī bih rīshahʹhā-yi tārīkhī-i harakatʹhā-yi zanān dar Īrān [The Ladies’ Center with a focus on the historical roots of women’s movements in Iran] (Tehran: Muꜥassisah-ʾi Mutāliꜥāt-i Tārīkh-i Muꜥāsir-i Īrān, 1383/2004), 129–35. Siddīqah Dawlatābādī, who served as the president of the Kānūn during its second phase, extended invitations to active women to join the organization.39Nūr al-Hudā Manganah, Sarʹguzasht-i yak zan-ī Īrānī yā shimmah-ī az khātirāt-i man [The story of an Iranian woman or a sketch of my memories] (Tehran: Rūzʹnāmah-ʾi Pust-i Tihrān, 1384/1965), 88. Fakhr ʿUzmā also became a member and continued her activities within the Kānūn, although she was never able to replicate the experience she had with the Jamꜥīyyat-i Nisvān. This was due to the fact that the Jamꜥīyyat-i Nisvān was a community-based organization with greater freedom to pursue its objectives, whereas the Kānūn was a fully governmental body that adhered to state policies.

In 1317/1938, Fakhr ʿUzmā got a license to publish the newspaper Nāmah-ʾi Bānuvān-i Īrān (Iranian women’s journal), but since it didn’t generate enough income, she eventually stopped publishing it. In the 1300s/1920s, she also secured a license for another newspaper named Āzādī-i Khalq (Freedom of the people), but unfortunately, no archives of this newspaper have survived. Alongside all these activities, Fakhr ʿUzmā and Jamāl al-Dīn Khalꜥatbarī decided to establish the Anjuman-i Dānishvarān (Society of scholars), which met every Friday evening at their home, where various poets would gather to read their poetry. Saꜥīd Nafīsī, Malik al-Shuꜥarā Bahār, Rashīd Yāsamī, Muhammad Husayn Shahriyār, ꜥAbbās Furāt Yazdī, and others attended these gatherings, and Fakhr ʿUzmā and her husband published the works of these poets and scholars in Āyandah-ʾi Īrān.40Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 289–90.

Fakhr ʿUzmā’s Poetry

According to Sīmīn Bihbahānī, a total of 150 poems by Fakhr ʿUzmā have survived.41Bihbahānī, “Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn dar guftugū bā dukhtarash (Sīmīn Bihbahānī),” 24. Of these, 54 poems can be found in the surviving issues of Iqdām, Āyandah-ʾi Īrān, and ꜥĀlam-i Nisvān, as well as in a poetry collection that came into Sīmīn Bihbahānī’s possession. This collection, which contains 30 of Fakhr ʿUzmā’s poems, was published as an appendix to the book Bā mādar-am hamrāh.42By examining all available issues of Āyandah-ʾi Īrān (1309–1320/1930–1941), ꜥĀlam-i Nisvān (1299–1313/1880–1934), Nāmah-ʾi Bānuvān-i Īrān (1317–1319/1938–1940), Jamꜥīyyat-i Nisvān-i Vatanʹkhvāh-i Īrān (1302–1305/1923–1926), as well as reviewing the poetry annexed to Bā mādaram hamrāh, only 54 poems by Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn were found. Sīmīn Bihbahānī herself mentioned that she never had the opportunity to collect her mother’s poems: “I have nothing from her except a notebook with about 30 ghazals and qatꜥahs. Perhaps something from her can be found in the newspapers Āyandah-ʾi Īrān and Nāmah-ʾi Bānuvān (the two newspapers she herself published), as well as in older newspapers and magazines. I should go to the National Library or the Majlis Library. But there’s no mood or energy for it. Everyone must collect the fruits of their own work in their own time.” See Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 106.

Fakhr ʿUzmā’s most preferred poetic form was the ghazal, in which she composed 36 poems, addressing both social and romantic themes. The second most prevalent form she employed was the rubāʾī (quatrain), in which she wrote eight poems, using this form exclusively to discuss social issues. The third most frequently used form was the masnavī(rhymed couplets), which she utilized five times to explore contemporary social matters. She employed the shish-gānah(the six-fold) poetic form and the rubāʾī twice, and used the tarkībʹband (composite verse) once. Aside from the rubāʾī, she used the other two forms to address social concerns. Most of Fakhr ꜥUzmā’s poems, published in the newspapers of her time, present innovative content. Indeed, the value of these poems lies in their modern thematic focus, while their structure, syntax, and rhetoric do not present any particularly groundbreaking features. Her poems use a language rooted in classical tradition, with a syntax similar to that of earlier generations of poets.

Among the themes Fakhr ꜥUzmā favored in her poetry are the necessity of acquiring knowledge, the veil (hijab), the pursuit of women’s rights, politics, patriotism, and love. It appears that during the early Pahlavi period, knowledge was seen broadly, not just in one specialized area. For instance, Sīmīn Bihbahānī comments on her mother’s education, stating: “She became familiar with fiqh and usūl, the Quran, Arabic, mathematics, physics, chemistry, and even philosophy, astronomy, and astrology through years of study in this very school.”43Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 27–28. Bihbahānī also underscores her mother’s profound understanding of scientific topics by referencing an incident that occurred during her marriage proposal ceremony. She describes her mother standing by the room door, holding a tray of sharbat (sweetened beverage), and raising the topic of light refraction: “The spoon in the glass of sharbat appeared to break where it dipped into the water. Fakhr ꜥUzmā recalled Mīrzā Abū Tālib Khān Bahr al-ꜥUlūm saying: ‘Light refraction!’”44Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 5–6. A similar approach to science is evident in the journal ꜥĀlam-i Nisvān, some issues of which feature a column of scientific questions, such as: “Why is thunder more frequent in summer than in winter?”, “Why is the sunset often red?”, “Why are some people unable to distinguish different colors?”45ʿA. M. ʿĀmirī, “Ittilāʿāt-i ʿilmī-i shumā bi chih darajah ast?” [What is the level of your scientific knowledge?], ʿĀlam-i nisvān 7, no. 2 (Bahman 1305/1927): 45. Such questions included in a popular magazine like ꜥĀlam-i Nisvān suggests that “educated women” of the time were expected to be familiar with the answers. Even in publications prior to 1300/1921, such as Shukūfah (Blossom), we see that shawhardārī (housekeeping) was referred to as a science. Discussing why women during the Pahlavi era—whether educated or not—were expected to know the answers to these questions requires further exploration. However, raising this expectation provides valuable insight into Fakhr ꜥUzmā’s conception of knowledge, which should not be confused with the modern definition of knowledge, which has come to mean specialized, in-depth knowledge grounded in scientific methodology—knowledge defined not by the breadth of general information but by the quality of research and the degree of expertise:

“I will set fire to the darkness of ignorance with the torch of knowledge,

From a wise thought that I establish,

I will raise the flag of knowledge in the land of ignorance,

and stir up a rebellion like Kāvah the blacksmith,

I will place the maddened head under the foot of knowledge,

I will gather my witness to my side and make my heart happy.”46Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Chand?” [How many?], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, no. 48 (1310/1931): 3.

The poet is trying to express that she will dispel ignorance through the light of knowledge. She presents herself as a rebel—like Kaveh the Blacksmith—who fought and defeated Zahhak. Here, Zahhak symbolizes an age of darkness and ignorance. The poet is willing to give her life for the sake of her country and, of course, for knowledge. After overcoming the ignorance that has surrounded her homeland, she will celebrate this victory with her beloved.

The emphasis on acquiring knowledge is the most repeated theme in Fakhr ꜥUzmā’s poetry:

“The presence of wise people is the symbol of prosperity,

He who lacks knowledge is like a barren tree.

The wealth of every country is its knowledge,

If knowledge is absent, the country falls into poverty.”47Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 641.

This theme on the importance of knowledge continues in another ghazal:

“I have nothing in my mind except the desire for knowledge,

My soul, body, and head, all are sacrificed for knowledge,

All the buildings will collapse in time,

But the building of knowledge will never collapse or fade,

It is recorded on the page of the world,

that the lifespan of those who dedicated their life to knowledge is honored,

If you want the cure for your country’s pain,

You must treat it with the medicine of knowledge.”48ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Kujā būdam, dar kujā hastam!,” 40.

However, the poet’s emphasis on knowledge is particularly directed toward women. In this couplet, she says:

“If a mother lacks the art,

And no knowledge is in her,

The child she raises in her lap,

Will be as unfortunate as she is.”49Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Mādar-i bī-ʿilm” [The uneducated mother], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, no. 54 (1310/1931): 3.

Or in another ghazal, she writes:

“Your hair is all twists and turns, curls, and knots,

Your teeth like pearls, and your lips like a blossoming rose,

If you wear a dībā (silk garment),

Your presence becomes entirely charming and beautiful,

If you lack dignity, piety, and virtue,

You will be seen as lowly in the eyes of discerning people,

Without knowledge, you are like a flower without fragrance,

If you are neglectful of art, disgrace will follow you everywhere,

If you have knowledge, virtue, and purity,

Honor will follow you everywhere.”50Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Ay dūshīzah-ʾi imrūz – ay mādar-i fardā” [O maiden of today – O mother of tomorrow], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 12, no. 28 (1320 /1941): 2.

The fact that Fakhr ꜥUzmā specifically emphasizes that women should pursue education is a common discourse frequently seen in the written works of this period. Many intellectuals of the time believed that a mother’s lap is the child’s first school, and the mother herself is the first teacher. Therefore, women must be educated so that their children can secure a bright future for the country: “Now one should understand why Americans place such importance on educating women, and the answer is very simple: Americans know that their present and future depend on the existence of mothers. It is the mother who raises the children. It is the mother who nurtures an Edison in her lap. If the mother herself is devoid of the adornment of knowledge, how can she possibly raise learned sons and daughters? How is it possible for a child raised in the lap of an ignorant mother to grow up virtuous and knowledgeable?”51Kokab Qaem-Maqami, “Zan dar Iran” [Women in Iran], ꜥĀlam-i Nisvān 7, no. 7,8 (1306 /1927): 259.

Thus, women should pursue education not because they are citizens with a right to learn, but because they have the responsibility of educating the next generation.

The second theme is the veil. Fakhr ꜥUzmā was very religious and avoided even the slightest trace of alcohol, rinsing her mouth if needed. She also composed a ghazal in praise of the first Shiite Imam, ꜥAlī ibn Abī Tālib, and in another ghazal, she admires Mahdī, the hidden Imam of the Shia:

“Do you know what today is, the feast of ꜥAlī, the master of religion,

Companion of the essence of ‘Allah’, the manifestation of divine benevolence?”

Or:

“Oh God, remove the dust of calamity from the heads of the people,

May the auspicious fortune return, and happiness come back,

The King of the World, the pride of the age, our master Mahdī,

Even the dust of his footsteps could restore clarity to Fakhrī’s eyes.”52Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 638–45.

Interestingly, despite her strict religious observance, the existing photographs of Fakhr ꜥUzmā show her without a veil, suggesting she was not committed to wearing the hijab.53Before the law mandating uniform clothing was implemented, women had already abandoned the chador and begun wearing hat. In an interview with the Bunyād-i Mutāliꜥāt-i Īrān (the Foundation for Iranian Studies) on May 22, 1984, Mihrangīz Dawlatshāhī claimed that the removal of chadors had begun several months before Day 1314/December 1935, and that ministries as well as the Majlis had invited their members to attend gatherings with their unveiled wives: “The ministries sent out invitations, the Majlis did too—naturally, all under the government’s direction. But even a few years earlier, there were already households where men and women first began socializing together inside the home and then gradually stepped out into the streets without chadors.” (Mihrangīz Dawlatshāhī was an Iranian woman who served three terms as a member of parliament and, in 1975, became the first woman in Iran to be appointed as an ambassador (to Denmark). In addition to her political work, she had a long history of advocating for women’s rights and social causes; she was active in parties and organizations and founded the Rah-e Now Association to support women’s participation and rights).

According to Sīmīn Bihbahānī, Fakhr ꜥUzmā at least wore a chador during Sīmīn’s childhood: “My mother’s chador was embroidered with perforated flowers, and I caught its fragrance in the purple-blossomed trees—their scents were the same.” See Sīmīn Bihbahānī, Kilīd va khanjar: Qissahʹhā va ghussahʹhā (Tehran: Sukhan, 1379/2000): 16. Sīmīn was born in 1306/1927, but due to Fakhr ꜥUzmā’s work commitments, she started school earlier than usual: “[Mother] spoke with Tūbā Khānum Āzmūdah, the director of the Nāmūs School. She also taught there herself. It was decided that I, not yet five years old, could join the preparatory class as a free listener.” Sīmīn recalls her first day at school: “Mother wore a black chador. She had tied its strap around her waist, and pulled the pīchah down like a black, hair-like canopy over her gold-chain pince-nez glasses.” This suggests that Fakhr ʿUzmā continued wearing a chador and pīchah when outside, at least until 1311/1932. See Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 186, 197. Her rejection of the veil was evident not only in her appearance but also in the poems she wrote:

“It would be a shame to cover such beauty with a veil,

The flower of vitality and elegance would fit your face beautifully,

Your beauty, oh flower, is so great that even the nightingale,

Cannot stop singing in your presence.”54Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Ay zan!” [O woman!], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, no. 49 (1310/1931): 4.

However, certain contradictions regarding the veil appear in Fakhr ꜥUzmā’s poetry:

“If you grasp the veil of knowledge in your hand,

The dark night of ignorance will pass, and the dawn will come,

O woman! If you lack knowledge, your life will be empty and fruitless,

A dark cloak is no barrier to progress,

Light can be seen even behind the veil,

The path to progress is not just about unveiling,

The path of knowledge is the true way if you pass through it.”55ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Ay zan!,” 1.

In any case, the overall message of her poetry suggests that she was an advocate for women’s rights and did not present the veil in a positive light:

“How long shall we remain drowned in the cradle of ignorance?

Forever intoxicated by the wine of heedlessness,

Always bound by shoes, veil, and mask,

In the dark shroud, we linger like crows.”56Fakhr-i ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Tarkībʹband-i bahāriyah” [Spring poem in the tarkībʹband form], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, nos. 58–59 (1311/1932): 2.

Or in another ghazal, she says:

“O beautiful face, you must come out from behind the curtain,

Open your eyes and look around,

Purity and spirituality must guide your path,

You must wear a clean and honorable chador on your head.”57ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Ay Zan!,” 1.

In a ghazal recited on Tīr 8, 1326/June 29, 1947, during the second year of the Sāzmān-i Zanān-i Dimukrāt-i Īrān (Organization of Iranian Democratic Women), she declared:

“Women of the country ask themselves,

Why must we walk under a dark shroud, like ravens?”58Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 651.

In the cultural atmosphere of the First Pahlavi period, many intellectuals opposed the veil, seeing it as an obstacle to women’s progress. In the works of these intellectuals, the veil is described with terms such as “dark shroud,” “hyena’s skin,” “coal sack,” “black skin,” and “black demon.” 59For example, see Delshad Chengizi, “Bayāne-i vāq’e” [The report of the event], ꜥĀlam-i Nisvān, 11, no. 3 (1310/1931): 100-101.

Another example of innovation in Fakhr ʿUzmā’s poetry is her support for women’s rights, which was one of her main concerns:

“Why should a woman in the land of Jam have no rights?

Come, let us pursue the fulfillment of women’s rights.

As we nurture brilliant men,

let us also refine women’s soul and body.

The purity of society comes, without question, from our efforts and endeavors.

Why should we leave this land and go elsewhere?”60Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 650.

In another ghazal, she writes:

“O early morning wind, carry my question to men:

Why is ‘weak woman’ [Zaꜥīfah] my name in this kingdom?

If I am the weak one,

then why is it left to me to raise strong men?”61FakhrʿUzmā Arghūn, “Asar-ī tabʿ-i dānishmand-i fāzilah Khānum Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn” [The work of the learned and esteemed scholar, Mrs. Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 1, no. 32 (1310/1931): 4.

One of the principal concerns among women activists of this period was the widespread consumption of alcoholic beverages by men. Aware of the consequences of this addiction, Fakhr ʿUzmā composed a masnavī entitled “Vazʿiyat-i khānavādah-ʾi alkulī” (The situation of an alcoholic family). In this poem, she first recounts the story of a family whose husband is addicted to alcohol, and then concludes with a moral lesson:

“There was nothing there but misfortune,

cruelty, poverty, suffering, and hardship.

From alcohol comes nothing but harm;

in this world, no one is unaware of it.

When the head of a household became addicted,

the very foundation of that home was destroyed.

O daughters of the Kingdom of Iran,

O young blossoms of the land of Sāsān,

to a man who, out of ignorance, worships alcohol,

who is forever drunk from the cup of wine,

make a vow that you will not tolerate such a husband.

Leaving such a man is better.

Whoever has knowledge and intelligence,

will not forget this advice.

Hang this counsel upon your ears,

for it is the most precious of all gems.”62Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Vazʿīyat-i khānavādah-ʾi alkulī” [The situation of an alcoholic family], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, no. 43 (1310/1931): 4.

Like Fakhr ʿUzmā, other intellectuals of the Pahlavi era believed that women, contrary to the laws of nature and solely due to the misguided customs of earlier generations, had remained in subordination to men and had been deprived of living in a humane world. Their aim in addressing the issue of women and describing the dire condition of Iranian women was nothing other than freeing them from the prison that men had constructed for them.63Issa Amankhani, tabārshenāsi-i naqd-i Adabi-i ideologic [A Genealogy of Ideological Literary Criticism] (Tehran: Khāmoush, /), 346. One of the ways women’s rights were advocated was through translating reports about the progress of women in other countries and comparing them with the situation of Iranian women. For example, ꜥĀlam-i Nisvān, featured an almost regular column titled “News of Women’s Advances,” consisting largely of translated reports on women’s achievements abroad. This section included news such as the granting of voting rights to women in Mongolia, the political involvement of Japanese women, female rulers in India, the participation of Greek women in elections, and more—all presented as implicit arguments for recognizing these same rights as the citizenship rights of Iranian women. See “Akhbār-i taraqiāt-ʾi Nisvān” [News of Women’s Advances], ꜥĀlam-i Nisvān 7, no. 4 (1306/1931): 159; 5, no. 6 (1304/1931): 18; 12, no. 1,3 (1311/1931): 2, 139.

Fakhr ʿUzmā closely followed political developments in Iran, and her interest in politics is evident in her poetry. For instance, she composed a ghazal in support of the Democrat Party and in response to the killing of Pīrzādah:

“The rightful principles of the Democrats endure in the world;

they remain, friends, as long as this world exists.

A group of empty-headed, unreliable men

Sows seeds of division— is this right?

We have chosen this principle and path with our lives;

the spirits of generous men bear witness to my words.

Look at Pīrzādah and other devotees,

their pure lives are devoted to you.

For the sake of the pure blood of our party’s martyrs,

I know of no price except upholding these principles.”64Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 642–43.

“Patriotism” is one of the most frequently recurring concepts in the press of the First Pahlavi era. Patriotism had effectively become a trend: a progressive and modern individual was, by definition, expected to be patriotic as well.65For example, See Delshad Chengizi, “Yāru” [An unknown person], ꜥĀlam-i Nisvān 3, no. 6 (1302/1923): 17-21. In this story, the traitor to the homeland is depicted as a reactionary and backward figure. In such discourse, anyone who lacks the markers of patriotism is subjected to strong collective condemnation.66For example, See Delshad Chengizi, “Radium Morājeat kard” [Radium Returned], ꜥĀlam-i Nisvān 5, no. 6 (1304/1925): 19-22. “Radium Morājeat kard” centers on a young woman who has studied in Europe and returned to Iran, illustrates this idea: instead of thinking about serving her country, she prefers to behave like Westerners and adopt their social manners. For this reason, The author calls this character’s behavior into question. Fakhr ʿUzmā was a nationalist as well, with Iran as her main concern, reflected in her patriotic poetry, such as the following ghazal:

“Rise, so that we may sacrifice our lives for the homeland.

Yes, for the soil of the homeland, let us give body and soul.

‘Long live Iran’ is our sole prayer;

let us make it our mantra in every gathering.

It is the woman whose child may become brave;

let us improve the situation with the help of both men and women.

Not only men sacrifice their lives for the homeland,

we too dedicate our lives to it.”67Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 648–49.

In this ghazal, Fakhr ʿUzmā includes women among the Iranian citizens, presenting them as devotees of the homeland. She uses “we” in a way that explicitly encompasses women, thereby incorporating them into the political discourse. Thus, “citizens” are not only men, but also women who wish to reform the country and actively participate in its cause.

When discussions of autonomy in Azerbaijan began, many expressed concern about the potential partition of Iran. Fakhr ʿUzmā, whose father was Azerbaijani and who traced her lineage to the Siqat al-Islām Tabrīzī family, strongly opposed the separation of Azerbaijan and criticized the Azerbaijani Democrat faction. On this occasion, she composed a ghazal:

“As long as I live, I am obsessed with Azerbaijan;

this obsession troubles my mind to the very core of my being.

May this head remain forever upon the body of Iran;

I am determined to guard it with all my strength.

I know Azerbaijani, I read Persian;

I am more than one person because I know more than one language.

Strength has become fused within me because I am Azerbaijani;

with zeal, I display the virtues of my ancestors.

The bond between Iran and Azerbaijan will never be broken;

I have certainty in this and faith in the defeat of our enemies.

May God protect this land from evil;

I entrust it to His care.” 68Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 648.

In another ghazal she mentions the working class:

“O fate, if only for once you would favor the worker as well;

May the traces of despotism vanish from this land and realm.”69Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 645.

Fakhr ʿUzmā came from a wealthy and privileged family, but she was never an advocate of keeping privileges confined to a particular class. In this poem, we see that she is concerned with class issues and seeks justice for workers. The poem reflects Fakhri’s worldview—one in which all social classes in Iranian society should progress. It is based on this worldview that Fakhri founded a girls’ school and enrolled students from disadvantaged groups there.

Fakhr ʿUzmā also wrote poems of romance and love, but without her pen name, Fakhrī, it would be impossible to tell they were written by a woman. Unlike her other topics, she demonstrates no particular innovation in her love poetry:

“I wish my beloved would come through my door and see me,

for his absence darkens my days like night.

My face was crimson like the lilac;

alas, it has turned saffron from grief.

From the twists of his black hair, tangled together,

see what entanglements have befallen me.

The day I behold his meadow-like features and flower-like face,

I am assured that my spring has been renewed.

Never blame Fakhrī for her love,

for my face and threads have been brightened by it.”70Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 639–40.

These ghazals adhere to classical aesthetic conventions, with the poet employing the imagery of eunuchs (or beardless youths) to characterize the beloved, drawing attention to the nascent beards of adolescent boys and their rosy, fair complexions. This motif recurs repeatedly in Fakhr ʿUzmā’s love poems:

“Lily-like, you have bound my heart in chains.

Why, now, do you treat this frantic heart so cruelly?

The black serpent of your hair [mār-i siyāh-i zulf] has ensnared us.

Why do you enchant us with your magical eyes [chashm-i jādū]?

Your ruby and garnet features, sweet as sugar [yāqūt va laʿl-i chūn shikar], give strength to our lives.

Why, then, make us sorrowful, with hearts bloodied by this gift of life?

O silver-statured Turk [Turk-i sīmʹbar], by depriving us of your beauty,

Why turn my home into a river of tears, like the Jayhūn?71Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 637.

Expressions such as “Turk-i sīmʹbar”, “chashm-i jādū”, “yāqūt va laʿl-i chūn shakar”, and “mār-i siyāh-i zulf” are masculine expressions typically used to describe young men. In her love poetry, the poet shows no innovation and relies entirely on classical literary devices. One exception shows a new element in her love poetry:

“The necklace around your neck, called a tie,

Is beautiful, yet your beauty completes it.”72Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 648.

In one poem, she compares her beloved to Joseph (Yūsuf), appealing simultaneously to both male and female perspectives:

“When Fakhrī becomes his purchaser, captivated by his face,

She shatters the prosperity of the marketplace of Joseph’s beauty in Canaan.”73Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 646–47.

Notably, the poet is innovative and pioneering in themes of politics, nationalism, and women’s rights, offering new content and forms. In contrast, in love poetry, she lacks an independent voice, composing entirely in the classical style and utilizing traditional aesthetic tools. This contrast reflects an important aspect of Fakhr ʿUzmā’s personality. For example, she composed a poem titled Shish-gānah (Six-fold). According to Āyandah-ʾi Īrān, the poem introduces “the new methods of Mrs. Fakhr ʿĀdil,” in which she drew inspiration for the six-fold poetic form from Shāhzādah Afsar:

“Nawrūz arrived, and the fields and meadows turned green / Adorned with tulips and flowers,

this ancient age became young once more.

O morning breeze, passing through land and village / Carry our congratulations to all,

wishing a prosperous New Year to our compatriots.”74Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Az tarzʹhā-yi nuvīn-i khānum-i Fakhr ʿĀdil” [On the new methods of Mrs. Fakhr ʿĀdil], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, nos. 58–59 (1311/1932): 1.

Fakhr ʿUzmā also composed another poem in this form:

“I said to a woman, O full-moon face / Why do you wrap your body in chador and pīchah?

Hurry out from behind the veil at this moment.

She whispered this softly in my ear / That I protect my face from the lustful gaze of men.

I strive to preserve my veil.”75Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Payruvī az tarz-i nuvīn-i Shāhzādah Afsar” [Following the new methods of Shāhzādah Afsar], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, no. 47 (1310/1931): 1.

Following the Constitutional Revolution, innovation in poetic forms became widespread. The six-fold form is one such example, which was employed as an exercise and did not resemble the classical forms of Persian poetry. This poem is, in fact, a six-line stanza where the first three lines share a single rhyme, and the last three lines follow a different rhyme. In the second example mentioned, the poet not only introduces innovation in form but also in content. She attributes women’s adoption of the veil to the immoral behavior of men who harassed them. Street harassment seems to have been common during the early Pahlavi period, as Sīmīn Bihbahānī mentions experiencing such disturbances herself and with her mother on several occasions.76Bihbahānī, Bā mādar-am hamrāh, 298–99, 596. Fakhr ʿUzmā also addresses these disturbances in another poem titled “Ālā-gārsūn” (À la garçonne):77“Ālā-gārsūn” [à la garçonne, garçon cut] was one of the most popular hairstyles among Iranian women following the royal decree on unveiling (Amriyah-ʾi Kashf-i Hijāb), issued in 1314/1935. In this hairstyle, the hair was cut very short, and Iranian women at the time embraced it enthusiastically. Interestingly, Fakhr ʿUzmā did not see women’s adoption of this style as a fashion trend; instead, she viewed it as a way for women to free themselves from men’s harassment.

“I said to the idol, ‘Your face is like the moon,

Why did you shorten those black tresses?’

She replied, ‘From the reach of lustful hands,

I feared, so I made my locks shorter.’”78ʿUzmā Arghūn, “ꜥIllat-i kūtāh nimūdan-i zulf,” 2.

Fakhr ʿUzmā also employed another new poetic form, which she herself invented. This form is a type of modern quatrain. These quatrains are brief enough to be categorized under continuous quatrains, yet they do not adhere to the meter of a rubāʿī and are not considered qatʿah, as they maintain rhyme (though, similar to qatʿah, they often contain themes of moral instruction). The number of Fakhr ʿUzmā’s poems written in this new form is relatively large, making it the second most frequently used form in her poetry. This indicates that the poet was intentional in her adoption of this innovative form.

“Now that you have freed yourself from restraint, O woman,

Clothe yourself in the garment of knowledge.

Then step into the arena of action,

And, with your own effort, make the homeland prosperous.”

Or,

“It is time for all women to work,

To awaken society through knowledge and action.

In service to the people, they must strive,

To rid the nation of its sickness and affliction.”

Or,

“The star of destiny, the strong-hearted child of Iran,

With its radiance, made the country of Jam the envy of the garden.

The foundation of the kingdom became firm with its strength,

And through its effort, the land of the Sassanids flourished.”

Fakhr ʿUzmā exclusively used this new form to address contemporary and social-political issues. As mentioned earlier, Fakhr ʿUzmā held a weekly literary gathering at her home, where she met with many poets in regular sessions. These meetings likely sparked her interest in innovation, both in form and content. For example, Shāhzādah Afsar, from whom Fakhr ʿUzmā drew inspiration for the six-fold form, was a regular member of Anjuman-i Dānishvarān (The society of scholars).

The Serialized Novel Izdivāj-i ijbārī (Forced marriage) and its Connection to Love Poetry

In addition to her poetry, Fakhr ʿUzmā also published short and long stories in journals. She is the first Iranian woman to publish a serialized novel in periodicals, one of which, titled Izdivāj-i ijbārī (Forced marriage) was published from 1310/1931 to 1312/1933 in Āyandah-ʾi Īrān.79Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Izdivāj-i ijbārī” [Forced marriage], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, nos. 35–36, 37–38, 41–48, 50–56 (1310/1931), 2, nos. 57–70 (1311/1932), 3, nos. 1–5, 7–9, 13, 16–17, 19–20, 22–24, 28–29, 32 (1311/1932), 4, nos. 1–4 (1312/1933). The novel centers on a cousin couple, Parīvash and Farīdūn, who, after years of separation, reunite and fall in love. Farīdūn is a modern, educated young man who falls in love with his modern, educated, and beautiful cousin Parīvash.80In the works of this period, an individual’s beauty is directly associated with their modernity, and modern men and women are generally considered beautiful. See Dilshād Changīzī, “Munāzarah,” ʿĀlam-i Nisvān 2, no. 1 (1300/1921): 35–40. The serialized novel Izdivāj-i ijbārī follows the same pattern, with both Parīvash and Farīdūn depicted as beautiful and modern. However, Parīvash’s future, forced husband, a reactionary and womanizing man, is described as “a 45-year-old man, unattractive and unpleasant, of short stature, with evil eyes and an arrogant, rude demeanor.” See Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Izdivāj-i ijbārī” [Forced marriage], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, nos. 57–59 (1311/1932): 12. In contrast, for example, in Molière’s plays—which were popular among Iranian constitutionalist playwrights—educated and cultured women are often depicted as very ugly and unpleasant. See Fātimah Mirnīsī, Safar-i Shahrzād [Shahrazad journey] (3rd ed. Tehran: Kirāsah, 1400/2021), 161–62. The love story between Farīdūn and Parīvash ends sadly because of Parīvash’s traditional father. However, there are several points in the story worth closer attention.

The first point to note is that Parīvash and Farīdūn share a close familial relationship, being cousins. Evidently, the author’s decision to make the two main characters relatives is not without significance, as Fakhr ʿUzmā seeks to present their relationship as non-sexual, initially alluding to their childhood memories of games and mischief to support this. She makes no reference to any prior romantic feelings between them, describing their past relationship as akin to that of siblings, such as a brother and sister. Even Parīvash’s parents mention several times that Farīdūn and Parīvash are like brother and sister.81Farīdūn has a monologue upon seeing Parīvash for the first time, struck by the spark of her charm and captivated by her appearance and figure. He thinks to himself: “What a grown and beautiful Parīvash she has become! That mischievous girl of the past is gone. Has she received any education? Is she learned?” He also reflected on thoughts like those of his cousin, remembering past days and the quarrels they had over toys, dolls, and the like. See Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Izdivāj-i ijbārī” [Forced marriage], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, no. 37 (1310/1931): 2.

Parīvash’s mother tells her: “Your cousin, with whom you have grown up since the age of two, will help you with English and piano. Of course, Farīdūn is also like our child—since we have no sons, he is as much our son as you are.” Her father also agrees: “Your uncle has confirmed as well, telling Farīdūn that Parīvash is like a sister to him and that he must help her advance in her studies.” See Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Izdivāj-i ijbārī” [Forced marriage], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, nos. 41–42 (1310/1931–32): 3–4.

Another important point is that Parīvash’s personal maid is an inseparable figure throughout the story, never leaving Farīdūn and Parīvash alone.82For example, when Parīvash and Farīdūn go boating, Parīvash’s maid accompanies them. At this moment, Farīdūn explicitly declares that he has no ill intentions in expressing his affection for Parīvash and refers to his guiding principle in life, namely “God – Love – Chastity”: “Parīvash! Look at those fiery letters on the other side, which read ‘God – Love – Chastity.’ I follow these words, and they are the laws of my life.” See Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Izdivāj-i ijbārī” [Forced marriage], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, nos. 43–44 (1310/1931): 4, 1. Her frequent presence in the duo’s conversations is meaningful. At first, it seems as though she is constantly with them because Parīvash’s parents have instructed her to be. However, as the story unfolds, we come to see that the maid’s presence serves a deeper purpose: the author uses her to signal that nothing sexual will happen between the two young characters, reassuring both Parīvash’s parents and the audience.83This analysis becomes particularly meaningful when we see that Fakhr ʿUzmā dedicates the first part of the story to fathers and mothers: “I am writing a small book called Izdivāj-i ijbārī [Forced marriage] and dedicate it to today’s mothers and fathers, so that they do not compel their daughters and sons in matters of marriage.” Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Izdivāj-i ijbārī” [Forced marriage], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, nos. 35–36 (1310/1931): 3.

Another aspect of the novel is that Fakhr ʿUzmā introduces details early on that she later alters. For example, in the initial sections of the story, she describes Parīvash as having a dark complexion, but later in the narrative, the author alters her appearance, making her fair-skinned.84In the second part of the novel, Fakhr ʿUzmā describes Parīvash’s appearance as follows:

“She had a tall figure, a slender waist, black tresses cascading to her knees, and striking black eyes and brows. Her face was long and graceful, with a touch of olive to her complexion.” See Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Izdivāj-i ijbārī” [Forced marriage], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, no. 37 (1310/1931): 3. However, in later parts, she decides to change her skin color: “Parīvash answered very slowly: I am ready to accept you as my husband. [Farīdūn] extended his hand and said: Promise that we will share both joy and sorrow together […] The girl extended her crystal-like hand, clasped the boy’s, and gave her word.” See Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Izdivāj-i ijbārī” [Forced marriage], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, no. 43 (1310/1931): 4. “[Parīvash], like an aged ascetic, secluded herself in a corner of the room, letting diamond-like tears fall upon her fair face, deeply moved and affected.” See Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Izdivāj-i ijbārī” [Forced marriage], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, no. 50 (1310/1931): 3. “It was as if a handful of thorns had been strewn across the pillow of this silver-bodied girl.” See Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Izdivāj-i ijbārī” [Forced marriage], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, no. 52 (1310/1931): 4. It appears that Fakhr ʿUzmā initially intended to present Parīvash as an Eastern beauty with a darker skin tone, a relatively common practice in the press of the time. As the story progresses, however, the author seems to feel the need to depict Parīvash with an ethereal, angelic quality, hence the shift to a fair complexion. As suggested by the character’s name—Parīvash, akin to fairies and angels—she is intended to embody the role of a “chaste” woman.

Another aspect worth mentioning is that throughout the story, the author repeatedly emphasizes that the love between Farīdūn and Parīvash is “sacred.” Even when they are unable to be together, she insists that they will be united in the afterlife as two angels.85For example, when Parīvash and Farīdūn go boating, the author describes the beauty of nature as follows: “It is as if nature itself accompanied these two pure and sacred beings, making its own beauty shine even more.”

Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Izdivāj-i ijbārī” [Forced marriage], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, no. 43 (1310/1931): 4.

In another section, Parīvash says: “Can a heart whose threads are woven with pure and sacred love, and whose soul is filled with affection, ever abandon love? […] You may think that now, since I have become another man’s wife, to feel this affection and love for you is an unforgivable sin. But my love for you is pure and sacred, untouched by any corruption. You and I pledged before our God to be husband and wife. What love could be purer, more sacred, or more innocent than the love of marriage?” See Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Izdivāj-i ijbārī” [Forced marriage], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 2, no. 61 (1311/1932): 4. The familial bond between the two main characters, the recurring presence of the maid, the beauty and name of the female character, the portrayal of Parīvash and Farīdūn as “angels,” and the depiction of their love as “sacred” all serve to normalize the romantic relationship between a man and a woman within Iranian-Islamic society. Fakhr ʿUzmā herself was a woman whose two marriages were seen as modern and romantic, and she aimed to promote this lifestyle. One could argue that her strategy for advocating this lifestyle was to demonstrate that a heterosexual romantic relationship could exist within the cultural norms of Iranian society and be regarded as socially acceptable. In her view, this approach would encourage social mixing between the sexes and promote the idea of romantic marriage.

There is a connection between the novel Izdivāj-i ijbārī and Fakhr ʿUzmā’s love poetry. Fakhr ʿUzmā was a talented poet, publishing her poems in popular journals from the age of nineteen. Although she possessed the capacity to innovate in both form and content, in her romantic poetry she remained constrained, adhering to the conventions of the classical style. Her conservative approach to writing a novel about a romantic relationship is also reflected in her romantic poetry, which shows no clear female perspective except when she adds her pen name “Fakhrī” in the final verse. She seems to have favored traditional aesthetics, carefully avoiding the sensitivities that modern trends might have provoked. Even in portraying the beauty of Parīvash or other characters in her novel, she shows little innovation, remaining wholly faithful to the classical tradition. Her metaphors are repetitive and conventional, such as comparing a figure to a cypress, hair to hyacinth, lips to ruby, and so on. It is unlikely that Fakhr ʿUzmā lacked the ability to innovate in romantic poetry; rather, she deliberately followed classical Persian traditions, conforming to social and religious norms. As a result, her romantic works lack a distinct female voice.

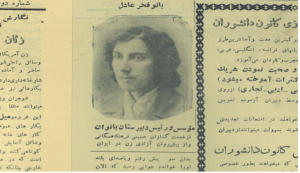

A photograph of Fakhr ꜥUzmā Arghūn published in Nāmah-ʾi Bānuvān-i Īrān 3, no. 2, 1319/1939).

The Influence of Nationalist Ideas

Fakhr ʿUzmā lived at a time when nationalism, celebrating the glory of ancient Iran, had many supporters.86Richard W. Cottam, Nationalism in Iran (Pennsylvania, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1978), 148. Iranians were moving away from a naive embrace of Western modernity toward a renewed pride in their heritage through a return to a particular past, selective national memory. One example of this trend toward archaism was the promotion of sarahʹnivīsī (pure Persian writing).87Rizā Bīgdilū, Bāstāngarāʾī dar tārīkh-i muʿāsir-i Īrān [Archaism in contemporary Iranian history] (Tehran: Nashr-i Markaz, 1380/2001), 140. Pure Persian writing was a movement in which words of Arabic, Turkish, and other origins were removed and replaced with words that were originally Persian. For instance, in 1308/1929, an article titled “Shād zī” (Live joyfully) was published in the journal ꜥĀlam-i Nisvān, offering alternatives for the commonly used terms of the era. These commonly used terms are mostly Arabic terms that have become established in the Persian language. However, the nationalists of the first Pahlavi era, largely due to anti-Arab sentiment, sought to purge the Persian language of these words and expressions88Many Iranian intellectuals of this period include anti-Arab themes in their works and express contempt toward this ethnic group. This trend largely stemmed from the historical defeat of Iranians by the Arabs and the humiliation associated with that defeat. One of the most anti-Arab intellectuals is Sadeq Hedayat, whose works clearly display racist attitudes. For instance, see Sādeq Hedayat, Mojtabā Minovi, Māziār(Tehran: Jāvidan, 1356/1977).:

“It is well known and evident to every Iranian that, after the Arab conquest of Persia, the Iranian people were, by force, deprived of their mother tongue and adopted many Arabic words. Today, anyone in our country, whether literate or illiterate, greets others with the phrase “Salām ʿAlaykum.” Fortunately, during the Pahlavi era, when the renewed history of our homeland was emphasized, the youth began greeting each other with the words “Shād zī” [Live joyfully]. In the morning, they greet with “Bāmdād nīk” [Good morning], at noon with “Nīmʹrūz khvush” [Happy Noon], in the evening with “Pasīn nīk” [Good evening], and at night with “Shab khvush” [Good night]. When parting, they say “Shād bāsh” [Be happy]. These terms were proposed by a graduate of the American College in Tehran, who also advised mothers to teach their children to use the phrase “Shād zī” in their greetings.”89Anonymous, “Shād zī” [Live joyfully], ʿĀlam-i Nisvān 10, no. 2 (Isfand 1308/March 1930): 55–56.

“Shād zī” had become a popular term among some intellectuals at the time. A few years later, Fakhr ʿUzmā herself published two poems under this very title in Āyandah-ʾi Īrān, with the second poem written entirely in pure Persian:

“Live joyfully, live, for Nawrūz has come, and the new year has begun

The world has come to life, and the fields and meadows are blooming.

In this new year, embark upon the path of endeavor and purposeful action.,

For through the power of action, one reaches their goal.”90Fakhr ʿUzmā Arghūn, “Shād zī” [Live joyfully], Āyandah-ʾi Īrān 3, no. 21 (1312/1933): 1.

And,

“O pure lineage of Iran, live joyfully

On such a joyous day, live freely.

For us, such a victorious day has come,

It is from King Jamshīd that we find delight in our hearts.

For us, another Nawrūz has arrived,

In the era of Pahlavi, justice is restored.

Iran, once in ruins,