Parvīn Dawlatābādī, the Poet of Childhood Innocence

Parvīn Dawlatābādī: Life and Works

Parvīn Dawlatābādī (1303–1387/1924–2008) was born in Dawlatabad, a town in the city of Isfahan. Her mother, Fakhr Gītī, served as the principal of the Nāmūs School in Isfahan, while her father, Hishām al-Dīn Dawlatābādī, was both a poet and a representative for the city.1Nāmūs School was among the first educational institutions for girls established by Muslim Iranians in 1283/1904. He was later appointed mayor of Tehran. After receiving her early education at the Nāmūs School, Dawlatābādī relocated to Tehran with her family. Upon completing high school, she intended to pursue studies in painting or sculpture at the College of Fine Arts. However, a visit to an orphanage had a profound impact on her, prompting a shift in focus. Deeply moved by this experience, she resolved to dedicate herself to working with children. She began her career in early childhood education, including a position at the Rustamʹābādiyān Kindergarten, a Zoroastrian institution. She also worked for approximately three years with the National Iranian Oil Company, where she was involved in worker training programs.2 Yaser Farashahinejad, “Parvīn Dawlatābādī: The Poet of the Literary Elite,” in Women Poets Iranica (Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation, 2024), https://doi.org/10.70501/wpiw6t1-qtz1.

During a visit to England, Dawlatābādī was introduced to the audiovisual educational tools, which at the time were largely unfamiliar in Iran. With the approval of the Ministry of Culture and Arts, she implemented these tools in classrooms for five years at the Shīvā Elementary School. Her collaboration with educators such as Fātimah Ikhtiyārī and Humā Bāziyār played a pivotal role in the success of these educational initiatives.3Muhammad Hādī Muhammadī and Zuhrah Ghāʾīnī, “Parvīn Dawlatābādī,” in Tārīkh-i adabiyāt-i kūdakān-i Īrān dar rūzigār-i naw 1340–1357 [The history of children’s literature in Iran in the new era 1961–1978] (Tehran: Chīstā, 1386/2007), 9:881. In 1339/1960, Dawlatābādī, along with her husband, Ismāʿīl Sārimī, and colleagues Parvīz Nātil Khānlarī and Zahrā Kiyā (Khānlarī), co-founded the Sukhan Publishing Company.4 Sukhan was also the title of a pioneering literary and cultural periodical, founded by Parvīz Nātil Khānlarī and published from 1322/1943 to 1357/1978. Although she advocated for the establishment of a division dedicated to children’s poetry within the publishing house, the initiative received little attention at the time.5Muhammadī and Ghāʾīnī, Tārīkh-i adabiyāt-i kūdakān-i Īrān, 9:881.

Long before she began writing poetry for children and young adults, Dawlatābādī had composed poetry for adult audiences from her teenage years. Her early works encompassed a range of classical forms, including the ghazal (a lyrical poem, typically expressing themes of love, loss, and mysticism, consisting of rhymed couplets with a refrain) and masnavī (a poem, usually in rhymed couplets, often telling a story or moral lesson), in addition to modern poetry. As noted by Simin Behbahani, Dawlatābādī’s composed and dignified demeanor discouraged her from seeking public attention. As a result, she rarely participated in literary gatherings and was selective in sharing her work. It was in recognition of this artistic integrity that Behbahani famously referred to her as “the poet of the chosen ones.”6Sīmīn Bihbahānī, “Bih yād-i Parvīn Dawlatābādī” [In memory of Parvīn Dawlatābādī], Bukhārā 82 (Murdād va Shahrīvar 1390/July and August 2011): 621.

Throughout her life, Dawlatābādī demonstrated an unwavering commitment to nurturing children through poetry. Her engagement with children’s literature began during her time at the orphanage, where she composed lullabies for institutionalized children. As an educator, she wrote poems and lullabies designed to address the emotional and psychological needs of children. Although many of these works remained unpublished, they served as a source of comfort and emotional refuge for the children in the institutions.

In response to a question about her choice to begin her work in children’s poetry writing with lullabies, she once remarked:

Lullabies are, by their nature, poems sung beside cradles. Traditionally, mothers sang them in a mournful tone. They sang songs such as this one: “Father came but didn’t come in / The traveler returns, but where have they been?” These words carried the weight of women’s voices, perhaps echoing the sorrowful tapestry of our nation’s feminine experience. But as I’ve noted in my book Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā (On the boat of clouds), I wanted my lullabies to be poems of awakening, not of sleep. That was what the children in orphanages, nurseries, and foster homes truly needed. It was necessary to whisper to them—again and again—of brighter tomorrows, broader horizons, and the promise of greener meadows yet to bloom.7Muhammadī and Ghāʾīnī, Tārīkh-i adabiyāt-i kūdakān-i Īrān, 6:773.

Her emphasis on “awakening” led her to compose lullabies distinct from traditional folk forms. While entertaining and musically engaging, her compositions were crafted to awaken children to the rhythm and beauty of language itself. One of the most significant aspects of Dawlatābādī’s poetry for children is its dialogical nature, its capacity to invite and encourage communicative participation from its audience. She elaborates on the importance of this engagement:

In the nurseries, what struck me most was that children deprived of a mother’s voice, under the care of overburdened nurses attending to many at once, grew up lacking both the opportunity to speak and to be heard. This deprivation affected their voices, their manner of speech, and their very words.8Muhammadī and Ghāʾīnī, Tārīkh-i adabiyāt-i kūdakān-i Īrān, 6:773.

In addressing this issue, Dawlatābādī identified one of her primary objectives in writing children as the establishment of a “lexical exchange” with her audience. An examination of both the poems she composed for children and her insightful theoretical reflections on the genre reveals her deliberate and sustained efforts to understand the specific psychological and emotional needs of her young readers. This endeavor is particularly notable given that, at the time, the very notion of “childhood” as a distinct developmental stage, and the corresponding attention to children’s needs, remained underdeveloped in Iranian society.

Following her tenure at the orphanage, Dawlatābādī worked at the Rustamʹābādiyān Kindergarten, where not only taught but also composed poetry specifically for children. Unfortunately, only a few of the poems she composed during this period have survived. However, one song titled “Ātash-i sadah” (The fire of the Sadah festival), believed by many scholars to be among her earliest works from this time, remains extant. Dawlatābādī performed this song with musical accompaniment during a Zoroastrian children’s celebration of fire at the kindergarten. This lyrics of the song are as follows:

O you fire, warm and bright

Red of your face, I gave you light

Yet from you, the hearth’s glow

And from you, the night’s bright

You are the warmth in our soul

You are crimson and pure

Your feast is the feast of being

It celebrates God’s foreseeing

O you fire, warm and bright

Red of your face, I gave you light9Muhammadī and Ghāʾīnī, Tārīkh-i adabiyāt-i kūdakān-i Īrān, 6:773.

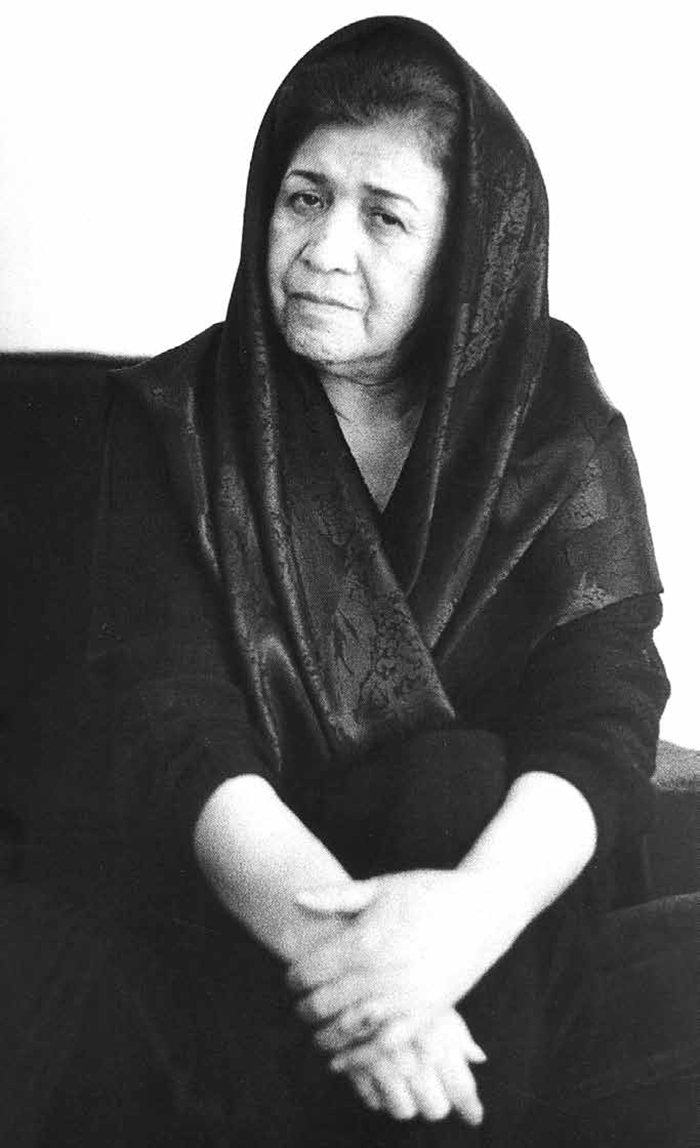

Figure 1: Parvin Dawlatābādī in orphanage. From Research Archive of History of Children’s Literature

These kindergarten poems are not refined examples of poetry. Rather, they continue the long-standing tradition of didactic and moralizing verse. The significance of Dawlatābādī’s contribution to Iranian children’s literature lies not in the poetic refinement of these early works, but in her gradual and deliberate departure from such traditional norms. In classical Persian literature, children were often addressed primarily through forms of advice, admonition, or instruction. However, following the Constitutional Revolution, the concept of childhood as a stage distinct from adulthood began to emerge, and this shift influenced developments in children’s poetry as well. Dawlatābādī played a pioneering role in the evolution of poetry for children in Iran.10Sūfiyā Mahmūdī, Adabistān, farhang-i adabiyāt-i kūdak va nawʹjavān [A dictionary of children’s and adolescent literature] (Tehran: Farhang-i Nashr-i Naw, 1392/2013), 128. The importance of her work becomes particularly evident when compared to that of earlier poets such as Īraj Mīrzā (1253–1304/1874–1925) and Parvīn Iʿtisāmī (1285–1320/1906–1941). Although these poets engaged with themes related to children and adolescents, they did not completely abandon classical structures or adult-oriented poetic traditions.

The pioneering efforts of educators such as Jabbār Bāghchahʹbān and ʿAbbās Yamīnī Sharīf, alongside a growing recognition of the importance of literature attuned to children’s unique cognitive and emotional worlds, contributed to the flourishing of children’s poetry in Iran during the 1320s/1940s through the 1340s/1960s. This period marked the first time poets could be meaningfully identified as “children’s poets.” Among these, Dawlatābādī and Mahmūd Kiyānūsh advanced further than their predecessors by emphasizing the child’s independent identity. By inhabiting the child’s perspective and expressing experiences from within that worldview, they became authentic voices of childhood emotion and perception. It is for upholding this groundbreaking approach that they are regarded as the founders of “modern children’s poetry” in Iran.

The most pivotal period in Dawlatābādī’s poetic career—and in the development of Iranian children’s literature more broadly—coincides with the emergence of magazines specifically devoted to addressing the needs of children. Among these publications, Payk, a magazine intended for kindergarten and elementary school students, played a particularly influential role. During this formative period, the majority of Dawlatābādī’s poems were published in Payk. She acknowledged that Payk and similar periodicals became vital platforms that enabled the publication and dissemination of children’s poetry. Some scholars estimate that Dawlatābādī composed over 500 children’s poems, most of which were published in Payk, while some appeared in textbooks.11Mahmūdī, Adabistān, farhang-i adabiyāt-i kūdak va nawʹjavān, 129. Dawlatābādī attributed her prolific output to an urgent desire to meet the pedagogical demands of the educational institutions with which she was affiliated, including the Rustamʹābādiyān Kindergarten and Khvārazmī School. These poems are now comprehensively preserved in the archives of Payk publications.

After the Islamic Revolution, a collection of Dawlatābādī’s poems—originally composed between 1325/1946 and 1355/1976—was published in a volume titled Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā.12Parvīn Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā: Majmūʿah-ʾi shiʿr barāyi kūdakān va nawʹjavānān [On the boat of clouds: A collection of children’s and adolescent poetry] (Shiraz: Dilgushā, 1377/1998), 14–15. Among her works that have been transmitted to the present are Qissah-ʾi murgh-i pāʹkūtāh (The tale of the short-legged hen, 1346/1967), Gul-i bādām (Almond blossom, 1366/1987), Gul rā bishnās kūdak-i man (Know the flower, my child, 1369/1990), each of which constitutes a significant and enduring contribution to the field of children’s literature.13Parvīn Dawlatābādī, Gul-i bādām [Almond blossoms] (Tehran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī-i Kūdakān va Nawʹjavānān, 1396/2017). Gul-i bādām was awarded the Poetry Prize of the Children’s Book Council (Jāyzah-ʾi Shiʿr-i Shūrā-yi Kitāb-i Kūdak), thereby cementing her legacy. In the years following the revolution, selections of her poetry were incorporated into primary school textbooks. Among her most enduring and widely recognized works are the poems “Khudā” (God) and “Bāz mīʹāyad parastū naghmahʹkhvān” (The swallow returns, singing). These poems, which continue to appear in fourth- and fifth-grade Persian textbooks, have become transgenerational artifacts, connecting multiple generations through poetic language and song.

Figure 2: The poem “Bāz mīʹāyad parastū naghmahʹkhvān” from Parvin Dawlatābādī in Persian literature book for elementary students during 1360s–1370s/1980s–1990s

Dawlatābādī passed away on Farvardīn 27, 1387/April 15, 2008, following a period of illness, ending a life marked by extraordinary cultural and literary contributions.

Stylistics of Dawlatābādī’s Children’s Poetry

“Care/Control Discourse” Period (Educational and Didactic Poems)

Different stages in Dawlatābādī’s poetic oeuvre reflect the profound political, social, and historical transformations experienced in Iran, particularly during the turbulent decades of the 1340s/1960s and 1350s/1970s. One of the most significant shifts occurred in public attitudes and state policies regarding children, which laid the foundation for a cultural transformation of childhood. A growing awareness of children’s vulnerability stirred the public conscience concerning the conditions of abandoned and orphaned children and contributed to the emergence of a “new ethics” in approaching childhood. The new ethical framework emphasized protection and humanitarian care. In this sense, marginalised, abandoned, and orphaned children became central to the formation of the new conceptualization of “childhood.”14Maryam Shaʿbān, Jāmiʿahʹshināsī-i kūdakī: Barsākht-i kūdakī dar Īrān [Sociology of childhood: The social construction of childhood in Iran] (Tehran: Jāmiʿahʹshināsān va ravishʹshināsān, 1400/2021), 96.

The emergence of what may be termed “childhood subjectivity” facilitated the development of a child-caringsociety and fundamentally transformed prevailing discourses surrounding child welfare. The growing emphasis on both care and discipline became particularly pronounced with the introduction of modern educational systems, particularly after the enactment of Iran’s Compulsory Public Education Act in 1322/1943. As kindergartens and modern schools proliferated, entertaining children became a priority.15Shaʿbān, Jāmiʿahʹshināsī-i kūdakī, 124–26. However, the primary thrust for entertainment primarily served to prevent mischief and trouble among children congregated in collective settings. As a result, cultural productions such as literature were frequently reduced to mere instruments of social regulation and behavioral discipline.

A substantial part of Dawlatābādī’s life was devoted to working with children in kindergartens, especially those without guardians in orphanages. She regarded her poetry as a response to the linguistic and developmental needs of such children. Accordingly, her early poems for children predominantly focus on educational and moral themes. Her work emerged within a society that was beginning to recognize childhood as a distinct developmental stage. This period also witnessed various pedagogical and literary experiments in defining this new conception of the child. At this historical juncture, children were initially framed as “abandoned others,” perceived by adults as subjects requiring control and correction. The following poem exemplifies Dawlatābādī’s engagement with the child during this early “care/control” period:

A quick-tempered, restless child

Drew lines on the walls and passed,

Placed dirty hands upon the doors,

Ruins followed where she passed.

She swallowed all she could devour,

Quick, unclean, with brutish power.

Until one day, before a mirror, she stood,

But could not know herself as she should.

The more she looked within the glass,

A child she saw unkempt and crass.

Her spirit, beautiful and young

No longer felt that she belonged.

She whispered softly, “This bad child

Has no place here; let it pass.

I, who am fairer than the rose,

Why am I cruel? Why so morose?

Why do my hands inflict such pain?

Why am I so mean and vile?

I must learn that life is kind,

That beauty thrives in a gentle mind.

Within my heart I revere

Whatever that is lovely, clear.

And what appears within this frame

Reflects the grace I failed to claim.16Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 14–15.

This poem illustrates the dominance of instruction and discipline in the landscape of children’s poetry during this period. The adjectives and descriptors used to describe the child highlight this orientation. A review of them confirms this point: “quick-tempered and restless,” “dirty,” “unclean,” “unkempt and crass,” “bad child,” “cruel,” “mean,” and “vile.”

Dawlatābādī was negotiating the challenges of this rigid poetic domain, navigating it through a process of trial and error. Many of these poems were recited exclusively in orphanages and kindergartens and were never published. This thematic orientation also characterizes the works of her contemporaries, indicating that early children’s poetry developed within a societal framework centered on the care and control of the child. Nevertheless, shifts in the cultural perception of childhood become evident in the later stages of Dawlatābādī’s career, which spans three decades. These shifts occurred amid broader social, political, and cultural changes—including the establishment of childhood-focused institutions, the rise of cultural criticism, the proliferation of academic seminars, increasing cross-cultural exchanges, and the translation of foreign works. These forces contributed to a profound redefinition of the child’s social status. Dawlatābādī clearly emerged as a significant figure within this evolving landscape, her writings meticulously chronicling the traces of these changes.

An analysis of Dawlatābādī’s children’s poems reveals that approximately 23 percent of her poems emphasize educational and moral instruction.17Zahrā Ustād′zādah, “Barrasī-i muhtavāʾī-i ashʿār-i kūdakānah-ʾi Parvīn Dawlatābādī (Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā va Gul-i bādām)” [A thematic analysis of Parvīn Dawlatābādī’s children’s poetry (On the boat of clouds and Almond blossoms)], Majallah-ʾi Markaz-i Mutāliʿāt-i Adabiyāt-i Īrān 3, no. 2 (1391/2011): 2. Although the didactic tone remains present throughout her body of work, it gradually gives way to more subtle, indirect methods of teaching, employing softened language and greater thematic diversity. The following poem exemplifies this transition, where the poet attempts to distance herself from overt moralizing by adopting the perspective and narrative voice of a child. Nevertheless, the presence of adult discourse and vocabulary rooted in classical poetic traditions remains discernible.

My daughter sat in the corner of the room,

A beautiful doll in her hands.

She said:

“My child, wash your face,

Comb your hair at dawn.

Speak the truth and never use foul words.

Find joy in speaking kindly.

Be kind and gentle with everyone.

Be polite, cheerful, and good.”18Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 14–15.

Even in poems composed explicitly for instruction, Dawlatābādī employs heightened imaginative elements and strives to approximate a child’s perspective and emotional world.

A little spider

Spun a delicate web.

A carefree tightrope walker,

It stretched the thread in every direction.

It clung to the threads,

Danced, and was full of joy.

It set a trap and caught prey,

Unaware of the wind.

The wind came, and in a single breath

Destroyed its home.

All it had spun was carried off by the wind

The spider was left tired and cold.

Like the spider, day and night,

Do not set traps in vain.

If you wish your shelter to remain,

Do not build your home in the air.19Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 122.

Dawlatābādī does not limit herself solely to the moral development of children; she also strives to impart a broad range of ethical and spiritual lessons. These poems adopt an advisory tone from an adult and maternal perspective. This didactic framework has significantly shaped her poetic language, rendering her diction rooted in classical Persian traditions. Of course, this duality between classical poetic tradition and modern poetry can also be seen in her poems for adults, reflecting the poet’s effort to move beyond a traditional perspective in poetry.20Farashahinejad, “Parvīn Dawlatābādī: The Poet of the Literary Elite.” This issue becomes even more noticeable in children’s poetry, due to the importance of language in that genre.

Rise, for the morning has come,

The day has arrived, a joyful day has come.

It has come to serve your needs,

May time align with your desires.

Rise and build your life,

You know you have this skill.

Be the maker of your own days,

Live with effort and your own work.21Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 81.

At times, Dawlatābādī employs an imperative tone, assuming the role of an omniscient sage dispensing advice to the audience. In such poems, not only does the language appear overtly adult, but the themes themselves—such as “the passage of time,” “inner purity,” “truth,” and “anxiety about tomorrow”—tend to lie outside a child’s natural concerns. The use of classical meter and diction further emphasizes this disconnect from childhood’s mental landscape. It may be argued that children of Dawlatābādī’s era—well-acquainted with texts like the Gulistān, the Bustān, and the Shāhʹnāmah—could engage with this elevated style and content. However, this familiarity arose simply from the lack of literary works genuinely crafted to their sensibility. What distinguishes Dawlatābādī, who has been aptly named “the children’s poet,” from her predecessors, including Parvīn Iʿtisāmī and Malik al-Shuʿarā Bahār, who also composed poetry for young audiences, is her pioneering quest to forge a distinct poetic realm for children, one in which child audience could engage with a language and expression uniquely their own. In her transition from a classical poet writing for adults to a children’s poet, Dawlatābādī, at times, lingers in a liminal space between the two.

He asked: “In your eyes,

Do you bear a sign of light and purity?

How beautiful this shell-like chest is.

There is a gem within; do you recognize it?

If there is a head upon this body,

There is passion and mischief in it, do you know it?

Life is in your hands, look,

Do not let it slip away in vain.

The wealth of your being is your lifetime,

Be warned, and do not waste it in heedlessness.”

I said to myself: “Return to your true self,

Be clear as a mirror and pure of soul.”22Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 17.

What has been discussed regarding Dawlatābādī’s didactic poetry is equally applicable to the transitional phase of children’s poetry more broadly. In comparison with her contemporary children’s poets, it becomes evident that Dawlatābādī made more deliberate and sustained efforts in this regard, undergoing a gradual and consistent evolution.23For example, one can refer to the poems of ʿAbbās Yamīnī Sharīf, who, like other children’s poets of this period, openly engages in commanding and forbidding children in some of his poems; the following poem is one example of his work:

Hey, hey, dear child,

Don’t throw stones in the alley.

If you throw a stone, you’ll break a head

God forbid, suddenly…

If you break a head, gush, gush,

Blood will pour from that spot.

The owner of the head will shout

“Hey, officer! Hey, officer!”

He’ll take you to the police station,

With force, dragging you along.

Directly instructional poetry for children is a common feature in societies that are only beginning to recognize the distinct the concept of childhood. It is only in the later stages that both in Dawlatābādī’s work and that of other children’s poets, the initial reliance on didacticism and the absence of imaginative elements begin to give way to a more nuanced engagement with the cognitive and emotional world of children. This transformation is marked using age-appropriate language, sensitivity to children’s interests and desires, and the integration of joyful playfulness by careful selection of appropriate poetic meters. The shift from a societal focus on controlling children to one that centers their worldview played a decisive role in reshaping children’s poetry during this period.

This same progression in perspectives on childhood and children’s poetry is evident in Dawlatābādī’s other works. In her collection Gul-i bādām (published in 1367/1987 but composed during the 1350s/1970s), one observes the adoption of a child’s perspective, the inclusion of themes suited to a child’s comprehension, the use of fluid and accessible language, rhythmic meter, and the cultivation of childlike imagination through literary devices such as similes and personification.

Colorful, beautiful butterfly,

You’ve come again to our home.

You sit in the corner of the window

To see the lovely garden.

My pretty, colorful guest,

My lovely little playmate,

Today, as the beautiful buds

Smile upon our faces,

I open this window wide,

Come, my butterfly, and fly.24Dawlatābādī, Gul-i bādām.

An analysis of Dawlatābādī’s poetry reveals that during her transition from explicitly didactic verse to a perspective oriented toward children, natural imagery played a constructive and enabling role. Other scholarly studies confirm that nature-themed poems, which focus on the detailed depiction of natural elements such as water, fire, wind, rain, and the seasons, constitute the largest proportion of her poetic output, accounting to approximately 33 percent of her corpus.25Ustādʹzādah, “Barrasī-i muhtavāʾī-i ashʿār-i kūdakānah-ʾi Parvīn Dawlatābādī,” 2. This should not be interpreted as indicating a linear evolution in her thematic development. Rather, the natural world provided the poet with a transformative narrative lens, which facilitated her deeper engagement with the sensibilities of young audiences. The process of discovering an ideal poetic language and rhythm was gradual and iterative. For instance, her poems centered on the wind demonstrate this transitional phase through their dual engagement with both adult poetic conventions and emerging child-centered expression.

The wind was passing gently and singing:

“Truly, tell me, what is my name…?

The willow is my familiar friend,

Its graceful dance is meant for me…26Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 58.

Morning came, and a breeze,

Softly and on tiptoe,

Moved across the courtyard pool,

Making ripples on the water…27Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 60.

However, some scholars argue that this naturalistic tendency in Iranian children’s poetry—alongside its emotional tone, nostalgic ambiance, and journey motifs—reflects the continuing influence of a romantic sensibility, which remains observable in the works of contemporary poets writing for children.28Ali Armaghan, Reza Shajari, Maryam Jalali, and Alireza Fouladi, “The Characteristics of Romanticism in the Children’s Poem in Iran,” Advances in Language and Literary Studies 7, no. 5 (2016): 59–63.

The Child-Oriented Period (Imaginative and Emotional Poetry):

The 1340s/1960s and 1350s/1970s represent the golden age of Persian children’s poetry, marked by seminal institutional developments, including the founding of the Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī-i Kūdakān va Nawʹjavānān (Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Youth)29Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī-i Kūdakān va Nawʹjavānān is a cultural institution dedicated to the production and dissemination of artifacts for children and adolescents. It was founded by Laylī Amīr Arjumand in 1344/1965. and the establishment of the Shūrā-yi Kitāb-i Kūdak (Children’s Book Council).30Shūrā-yi Kitāb-i Kūdak is an independent and non-governmental organization founded in 1341/1962 to help flourish and enrich children’s literature. This transformative period witnessed the launch of influential cultural initiatives, such as the Payk magazine series, which began in 1343/1964 and quickly emerged as a defining platform for the genre. These two decades also marked the artistic zenith of Dawlatābādī’s career, particularly through her sustained creative collaboration with Payk publications, including Payk-i Nawʹāmūz (Educator’s message), Payk-i Kūdak (Children’s message), and Payk-i Nawʹjavān (Youth’s message), where many of her most enduring works were first published.

Figure 3: The poem “Sitārah-ʾi man” by Parvīn Dawlatābādī, published in Payk-i Nawʹāmūz magazine, Urdībishisht 1352/May 1974.

The editorial philosophy of Payk conceptualized children’s poetry as a vibrant synthesis of dance, song, music, and color in an imaginary world. The magazine’s selection criteria prioritized works that encouraged children’s direct and imaginative engagement with objects and living beings in their natural states, with the aim of fostering emotional intelligence and creativity. Characterized by rhythmic energy, straightforward language, and vivid imagery, the poetry featured in Payk laid the groundwork for upcoming transformations in Dawlatābādī’s poetic outlook.31Muhammadī and Ghāʾīnī, Tārīkh-i adabiyāt-i kūdakān-i Īrān, 10:987.

In his book, Shiʿr-i kūdak dar Īrān (Children’s poetry in Iran, 1352/1973), Mahmūd Kiyānūsh, a close colleague of Dawlatābādī at Payk, analyzes these shifts in conceptualizations of childhood and children’s poetry during this period. This work is among the earliest attempts to theorize Persian children’s poetry. Although grounded in personal experience, it effectively encapsulates the dominant poetic ethos of the time, especially when Kiyānūsh invokes Dawlatābādī’s verses as paradigmatic illustrations of his theory. The book reveals that imagination and emotion were the defining features of children’s poetry during this period32Mahmūd Kiyānūsh, Shiʿr-i kūdak dar Īrān [Children’s poetry in Iran] (Tehran: Āgāh, 1352/1973), 21.—qualities epitomised in Dawlatābādī’s work. Kiyānūsh specifically observes:

Dawlatābādī alone was a children’s poet next to being a poet; when she turned to writing for children, she distilled fragments of her poetic essence into simple diction, clothing them in both classical and syllabic meters to gift to young readers. 33Kiyānūsh, Shiʿr-i kūdak dar Īrān, 37.

A comprehensive account of the children’s poetry of this era an understanding of how childhood subjectivity was conceptually framed. Kiyānūsh theorizes ‘childhood’ as the condition of the “primordial man,” undergoing separation from nature and responsive only to nature’s basal imperatives—namely, eating, sleeping, and playing.34Kiyānūsh, Shiʿr-i kūdak dar Īrān, 8. He argues that, like early humans, children possess greater imaginative capacity than rational thought, as their world composed more of ambiguity than certainty.35Kiyānūsh, Shiʿr-i kūdak dar Īrān, 21. Kiyānūsh reserves the title of “true children’s poet” solely for Dawlatābādī among his predecessors, consistently using her work to exemplify the themes he suggests for children’s verse.36Kiyānūsh, Shiʿr-i kūdak dar Īrān, 97. His method for selecting appropriate subjects for children’s poetry requires poets to return to their own childhood and observe natural phenomena through the eyes of a child. Regarding emotional expression, he defines emotions as system of action and reaction rooted in relationships, whether with people, living beings, or inanimate objects, and insists that they must be rendered through concrete, sensory imagery rather than through abstract concepts.37Kiyānūsh, Shiʿr-i kūdak dar Īrān, 99.

Kiyānūsh’s conceptualization of “childhood,” which profoundly influenced subsequent generations of poets and undoubtedly found its foremost exemplar in Dawlatābādī’s poetry, represents a pivotal transformation in the construction of childhood as a concept in Persian children’s poetry. It reflects a paradigm shift: from an approach that viewed children as subjects requiring control and moral instruction (expressed through adult-centered language and perspectives), toward one that acknowledged children’s imagination and emotionality, albeit still filtered through a relatively uniform lens.

Dawlatābādī’s poems demonstrate her deliberate effort to engage with the child’s imagination and emotions. Her use of descriptive language and behavioral thematics is often mediated through a maternal gaze, in which “the child is valued precisely for being a child.”38ʿAlī Asghar Sayyid ʿĀbādī, “Barrasī-i intiqādī-i dīdgāhʹhā-yi Kiyānūsh” [Critical analysis of Kiyānūsh’s perspectives], Pazhūhishʹnāmah-ʾi Adabiyāt-i Kūdak va Nawʹjavān 23 (1379/2000): 50. One might argue that “the maternal perspective” in some poems and the concept of “returning to one’s own childhood” dominate much of her poetic output. When examining the nurturing of emotions and conceptual development in her poetry, one encounters poems about fathers, mothers, and teachers, composed either from a maternal standpoint or drawn from the poet’s own childhood memories.

The home thrives because of you,

Clothes, water, and bread come from you.

Safety and comfort are from you.

From you, I learn loyalty,

Effort, tenderness, and sincerity

I love you, Father

May your shadow always be over us!39Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 101.

A similar tone and sentiment can be found in the following mother-themed poem, marked by its apt musicality and meter:

O your hands are my cradle,

Nurturing both my soul and body.

O your lullaby, the song of existence,

Each night you stayed awake, sitting with me.

You fed me milk, from the essence of your soul

Your hands and embrace became my home.40Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 75.

Throughout her life, Dawlatābādī wrote poetry that, as previously discussed, drew primarily upon the child’s imagination and emotional sensibilities, establishing a connection with nature through vivid imagery and lyrical expression.

One night, when the white moonlight

Spread its skirt over the earth,

I’ll hold onto its hem,

Its white and shining light.

I’ll flutter up to the sky,

I reach toward the galaxy,

I pick from up above

A diamond of a star,

So that I bring a gift for my mother41Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 42.

Undoubtedly, Dawlatābādī’s poetry, in comparison to that of her contemporaries, was rich in imagination and emotion. However, in the poems of this era, the lived experiences of children and the depiction of childlike actions received limited attention. Descriptions of nature, natural imagery, and childlike language and tone constitute the basic elementsthat Dawlatābādī integrated into her work to create her poetic works for children. Nevertheless, during this phase of her writing, the poet envisioned the child as “an object of innocence,” with minimal representation of actual childhood experience reflected in the poems. Moreover, although imagination is central to her work, it often remains constrained by conventional tropes and does not always transcend cliché. Still, it is essential to recognize that those pioneering poets who strove for change in their field, however critiqued by today’s standards, left an undeniable impact on their own time. These bold efforts to redirect the course of poetry paved the way for an art of criticism that has endured to this day. Dawlatābādī herself, in the preface to her book Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, reflects on her poetic experiences during those years, acknowledging both her aspirations and limitations.

What has been gathered over these long years is, in truth, the emotional and spiritual imprint of my blessed encounters with children and adolescents. This is a humble result of that encounter. I offer it with most profound gratitude.42Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 9.

It is therefore pertinent to examine the methods through which Dawlatābādī constructed imaginative frameworks in her poetry. An analysis of the nature of imagination in her children’s poems reveals that, in some cases, it does not fully embody the pure, childlike imagination born of genuine childhood experience. In certain poems, the imaginative framework relies heavily on personification by animating inanimate objects or by anthropomorphising animals. In these cases, shifts in narrative perspective and the introduction of alternative narrators serve to enable imaginative expression. Yet the dominant voice remains that of an adult speaker, one who delivers commands and admonitions. A representative example of this dynamic can be found in the poem “Faryād-i dīvār” (The wall’s cry), which is narrated from the perspective of a house wall defaced by children’s scribble.

Who drew the line?

Who drew the line?

On the door and the white wall?

I am the wall of this house,

White, clean, and bright.

This shelter of homes

Sits upon our foundation.

You draw lines on my body,

On my bright clothing.

Hey, why do you draw lines?

Hey, why do you draw lines?43Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 230.

Even within this framework, however, there are exemplary poems in which imagination flows organically through the narrative, tapping into genuine childhood experiences. Consider, for instance, the following poem, in which the poet personifies her own shadow by imbuing it with identity and agency. This poetic strategy transforms the familiar childhood experience of noticing one’s shadow into a lyrical meditation on companionship. Through the technique of defamiliarization, she elevates this everyday observation into something wondrous and new.

I walked with my shadow

From morning till night

It came with me, side by side

In step with me, gentle and light

I slowed my pace for just a while

It matched my stride, more mild

I told myself: your companion

Is your rival too, reconciled

When light was gone, it disappeared

Night cast the shadow into its snare

That weary foot stayed from the road

But I rebelled, if it did not dare…44Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 196.

Language and Music in Dawlatābādī’s Poetry

In children’s poetry, the language must primarily resonate with young audiences. This requirement has led many poets of children’s literature to adopt simplified vocabulary. Although this approach is not inherently flawed, it has unfortunately contributed to the perception of children’s poetry as a lesser form of adult poetry, often lacking in linguistic creativity.

Dawlatābādī’s poetry demonstrates a distinct command of language. The most significant linguistic feature in her work is the deliberate tension between archaic and contemporary simple vocabulary. The presence of these archaic terms is considerable. A detailed analysis of her poetry reveals the following usage frequencies for specific words:45Mansūr Pīrānī and Fātimah Bahrāmī Sālih, “Naqd-i zībāyiʹshinākhtī-i ashʿār-i kūdak-i Parvīn Dawlatābādī” [Aesthetic critique of Parvīn Dawlatābādī’s children’s poetry], in Majmūʿah-ʾi maqālahʹhā-yi dahumīn hamāyish-i biyn al-millalī-i Anjuman-i Tarvīj-i Zabān va Adabiyāt-i Fārsī [Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference of the Association for the Promotion of Persian Language and Literature] (Muhaqiq Ardabilī University, 1394/2015), 625.

Archaic and rare compound phrases also appear in Dawlatābādī’s poetry, and they occur with greater frequency than isolated archaic words.46Pīrānī and Bahrāmī Sālih, “Naqd-i zībāyiʹshinākhtī-i ashʿār-i kūdak-i Parvīn Dawlatābādī,” 625.

This feature extends to the use of verbs. Archaic verbs, such as khuftan (to sleep, rest, slumber), kishtan (to till), khamūdan (to calm down, subside, become silent), gushūdan (to unlock, unseal, unfold, unfasten, reveal), bar-āmadan (to rise, emerge, appear, surface, come forth), bar-bastan (to fasten, bind, shut, secure, lock), az kaf burūn kardan (to lose, forfeit, misplace, squander) and bih khvīsh bāz āmadan (to regain consciousness, to awaken, recover, revive) appear frequently in Dawlatābādī’s poetry. this stylistic phase in Dawlatābādī’s work has previously been examined, with relevant examples drawn from her poems. However, in her other works, particularly her poetry for children, a distinct shift is observable. Her children’s poetry is characterised using simple, familiar, and age-appropriate vocabulary. The careful acknowledgment of the audience, and the selection of language suited to their mental and emotional development, reflects the deliberate artistic trajectory Dawlatābādī throughout her poetic career.

Nevertheless, the question of language in children’s poetry is not confined to the issue of simple diction. Parvīn Salājaqah, in her study of children’s poetry in Iran, argues that much of what is currently categorized as children’s poetry in Iran, in fact, belongs to the realm of versification (nazm) rather than genuine poetry (shiʿr). She asserts that these works rely primarily on surface-level linguistic features, structured largely through formal elements such as meter, rhyme, and, occasionally, parallel structures (muvāzinah). Salājaqah contends that such versification has consistently been appropriated for educational purposes due to its rhythmic qualities. In contrast, authentic poetry, she maintains, involves a heightened use of language through linguistic foregrounding and a conscious departure from normative language patterns.47Parvīn Salājaqah, Az īn bāgh-i sharqī: Nazariyahʹhā-yi naqd-i shiʿr-i kūdak va nawʹjavān [From this Eastern garden: The theories of the children’s and adolescent poetry] (Tehran: Farhang-i Muʿāsir, 1385/2006), 288–90.

In children’s poetry, the limitations of such linguistic deviation cannot be overlooked. Nonetheless, certain examples in the genre illustrate a creative engagement with poetic language and musicality. One of the most frequent techniques employed in Dawlatābādī’s poems is the adoption of a child’s perspective, often utilizing childlike language. Although not all poems written from a child’s point of view demonstrate this linguistic quality, in some instances, the language appears to emerge directly from a child’s world.

I am a kite, I am a kite

I’m so light, I dance in flight

I have no wings, yet still I rise

And lift my head into the skies

No head is set upon my frame

No feet beneath my skirt to claim

The wind, the air, are under me

And every place is mine to be48Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 60.

As this poem demonstrates, the use of childlike language, combined with repetition, significantly enhances the poem’s musicality. Nevertheless, Dawlatābādī primarily relies on “external musical devices”—such as varied metric patterns (ʿarūz rhythm), rhyme, and refrains—rather than internal linguistic foregrounding, to construct the rhythm of her poetry.

O golden-haired sun,

You who are high up in the sky,

Shine, shine brightly,

And melt the snow on the mountains.

Shine on the flowers,

And on the beautiful green grass.

From the branches,

Buds begin to sprout one by one.

Tell everyone that winter is gone

The flowers have come to the garden.49Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 188.

As noted earlier, Dawlatābādī often positioned herself between the language of classical or adult poetry and the perspective of a child to craft her distinctive voice in children’s verse. This poem also reflects that duality in its lexical choices. Nevertheless, its childlike rhythm and musicality significantly enhance its appeal to young readers. In “Sitārahʹhā” (The stars), her use of childlike language, combined with a richer and more dynamic musicality, creates a world that resonates vividly with the energetic imagination of children.

Kind stars

Shine in the sky at night,

Winking and smiling,

Spreading light over the darkness.

They touch my hair with their hands,

Sending their light toward me.

The moon’s lantern in the sky

Shows the way through the night.

When I look at the moon,

I follow it on the path.

I gaze into the far distance

At all those beads of light.50Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 200.

Dawlatābādī primarily anchors the musicality of her poetry in the strategic use of varied rhyme schemes, deliberately selecting rhymes that align with children’s linguistic comprehension. This approach explains her frequent adoption of forms like the masnavi and chahārʹpārah (a poem consisting of several stanzas, each containing four hemistichs. Typically, in each stanza, the second and the fourth lines rhyme) structures, in which rhyme patterns shift across couplets and stanzas. These structures permit both rhythmic variety and accessibility for younger audiences. Owing to their narrative qualities, Dawlatābādī’s poetic structures retain remarkable coinherence. As it has been observed, “The rhymes in Dawlatābādī’s children’s poetry are consistently rich (multi-syllabic). Moreover, she employs elongated vowels and sonorous consonants, doubling the musical impact of her verse.”51Pīrānī and Bahrāmī Sālih, “Naqd-i zībāyīʹshinākhtī-i ashʿār-i kūdak-i Parvīn Dawlatābādī,” 627. Dawlatābādī’s children’s poetry employs “rich rhymes” (qāfiyah-ʾi ghanī), also known as “multi-syllable” rhymes.

Dawlatābādī was pioneering in her efforts to craft age-appropriate musicality, rhythm, and rhyme for children’s poetry. Kiyānūsh emphasizes the centrality of rhythm and rhyme in children’s poetry in the following way: “Before children can grasp classical poetic meters (buhūr), they intuitively recognize rhymed musicality. For them, what makes language ‘poetic’ is precisely its rhyme.”52Kiyānūsh, Shiʿr-ī kūdak dar Īrān, 59. He further identifies the ideal characteristics of metrics in children’s poetry: “First, these rhythms should not stray too far from the classical format of syllabic patterns; second, these meters ought to be short, lively, and dance-like.”53Kiyānūsh, Shiʿr-ī kūdak dar Īrān, 59–74. Dawlatābādī’s poems clearly reflect her deliberate and successful effort to achieve musical quality.

Figure 4: The poem “Gul-i bādām” [Almond blossom] published in the collection with the same title in 1366/1987 by Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī-i Kūdakān va Nawʹjavānan

The Audience of Dawlatābādī’s Poetry, the Audience of Modern Poetry (Shiʿr-i Naw)

Post-Revolution publications of Dawlatābādī’s works primarily compile poems written before the Revolution, many of which appeared in Payk magazine or in standalone collections such as Gul-i bādām and Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā. Her legacy is undeniable. Through decades of experimentation, she pioneered the very language of Persian children’s poetry—a patient, iterative process that fundamentally shaped the genre as it is known today.

However, the question remains: from the perspective of contemporary children’s poetry, what audience has Dawlatābādī’s work influenced? Kiyānūsh’s depiction of the child as possessing an “undeveloped, primitive imagination,” a characterization evident in Dawlatābādī’s poems, was long regarded as the manifesto of children’s poetry in Iran. While this was certainly a groundbreaking approach in its time, its effectiveness appears questionable in today’s world, where children’s vocabulary has significantly expanded due to exposure to diverse media.

Sayyid Ābādī observes that children and adolescents were historically viewed as “known entities,” meaning subjects whose needs, interests, and abilities could be easily identified. Nevertheless, themes in children’s poetry should instead draw from universal experiences shared by all children.54Sayyid Ābādī, “Barrasī-i intiqādī-i dīdgāhʹhā-yi Kiyānūsh”, 58. Contemporary approaches to children’s poetry adopt a more nuanced understanding of the audience, aiming to cultivate awareness and foster cognitive growth. In these modern frameworks, childhood is regarded as a dynamic process, rather than a fixed, fully formed concept steeped in sentimental romanticism.55Murtizā Khusrawʹnijād, Maʿsūmiyat va tajrubah: Darʹāmadī bar falsafah-ʾi adabiyāt-i kūdak [Innocence and experience: An introduction to the philosophy of children’s literature] (Tehran: Markaz, 1382/2003), 84.

Each work of children’s literature reflects a unique conception of childhood, as authors and poets offer their own interpretations of the term.56Khusrawʹnijād, Maʿsūmiyat va tajrubah, 28. An examination of Dawlatābādī’s poetry reveals that the dominant discourse shaping her work envisions childhood as an object of innocence—typically addressed through stereotypical vocabulary such as “pure,”57 Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 243. “light,”58 Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 74, 123. “spring,”59Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 74, 92. “affection,”60Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 74. “crystal,”61Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 74, 123. “flower,”62Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 123. “good,”63Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 242. “gentle,”64Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 73. and “sweet-faced,”65Dawlatābādī, Bar qāyiq-i abrʹhā, 242. and perceived as “innocent and blameless.”

Moreover, the dominant themes of Dawlatābādī’s poems, affection, vitality, empathy, unity, and joyful living, reflect an emotionally charged and innocent conception of childhood.66Muhammadī and Ghāʾīnī, Tārīkh-i adabiyāt-i kūdakān-i Īrān, 9:883. While such a perspective persists today, contemporary approaches to childhood demand a sharper focus on children’s cognitive development. It may be argued, however, that this perspective does not fully account for the diversity in children’s experiences, including their struggles and traumas. Nonetheless, Dawlatābādī’s work in her era laid essential groundwork by legitimizing children’s poetry as a genre worthy of critical and theoretical engagement. This achievement, unattainable without her decades of dedication and that of her peers, marks a pivotal cultural shift.