Networking Women Poets: Connecting Furūgh Farrukhʹzād and Adrienne Rich

Introduction

During the 1960s and 1970s, female poets relied heavily on translation to establish connections with one another. The primary objective of the first and second-wave feminism in translation was to articulate connections between female writers across the globe.1First and second-wave feminism aimed to connect women writers globally through translation, creating solidarity despite their differences. See Sherry Simon, Gender in Translation: Cultural Identity and the Politics of Transmission (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), 80. Female translators had a fundamental role in introducing the works of other women writers and intellectuals, forming new circuits of exchange. This effort is often referred to as transatlantic feminism.2Simon, Gender in Translation, 80.

Adrienne Rich, a renowned North American poet, feminist, thinker, essayist, and a pioneer of feminism in North America, played a crucial role in defending the rights of women, homosexuals, and African Americans through her works in poetry and prose. She is an author of two dozen volumes of poetry including Leaflets (1969) and The Will to Change (1971), and more than a half dozen of prose such as On Lies, Secrets, and Silences, Selected Prose 1966-1978 (1995); Blood, Bread, and Poetry, Selected Prose 1979-1985 (1984), and Arts of the Possible (2001), among which is “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision” (1971), her most important essay and one of the most outstanding works of feminist literary theory.

Rich had come across the poetry of the prominent Iranian poet Furūgh Farrukhʹzād, through a collection of poetry translation by Joanna Bankier entitled The Other Voice: Twentieth Century Women’s Poetry in Translation (1976).3Rich, Adrienne C, “Foreword,” in The Other Voice: Twentieth Century Women’s Poetry in Translation, ed. Joanna Bankier, et al (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1976), xvii-xxi. The collection included three poems by Farrukhʹzād: “Yak panjirah” (A window), “ʿArūsak-i kūkī” (The mechanical doll), and “Dilam barāyi bāghchah mīʹsūzad” (I feel sorry for the garden). She acknowledged that her first encounter with Farrukhʹzād’s poetry was made possible thanks to this collection of translations. In the forward she wrote for the collection, she elaborated on women’s network of connection and argued that female writers and poets should draw inspiration from other women’s writings to internalize their common sensibilities and powers. She believed that, for a long time, women had been oppressed and kept silent and isolated from one another due to their dependence on men. She named several female poets, including Farrukhʹzād, as powerful women who significantly impacted their societies’ poetic traditions and languages. Highlighting the poems of Farrukhʹzād for their ability to convey a sense of history, politics, and female existence, Rich praised the female poets in the collection for their efforts to break the dominant “male monologue” and end their silence.4Rich, “Foreword,” in The Other Voice, xvii-xxi. For this, she gave the example of Farrukhʹzād’s poem, “ʿArūsak-i kūkī.” Some stanzas of this poem read as follows:

You can stay there standing

by the curtain, as if deaf, as if blind.

You can cry out

in a voice utterly false and strange

“I love –”

You can, in the over-powering arms of a man

be a wholesome and beautiful female

with a body like a chamois spread

with large firm breasts.

You can, in the bed of a drunk, a vagrant, a fool

defile the chastity of a love.

…

You can be just like a mechanical doll

and view your world with two glass eyes.

You can sleep in a cloth-lined box for years

with a body stuffed with straw

in the folds of lace and sequins.

You can cry out and say for no reason at all

with every lascivious squeeze of a hand:

“Ah, how lucky I am!”5Hasan Javadi, and Susan Sallée, trans., Forugh Farrokhzad: Another Birth and Other Poems (Mage Publishers, 2010), 65–67.

Figure 1: From left: Portrait of Furūgh Farrukhʹzād, Adrienne Rich

Abandonment and Exile as Rebellion

The most notable aspect shared between the life stories of Farrukhʹzād and Rich, is perhaps abandonment, to which they reacted not as victims of exile but as instigators of self-exile from the boundaries of traditions. They abandoned their past lives and identities and opted for self-exile as a form of rebellion and change. Farrukhʹzād was born in 1313/1934 into an upper-middle-class family of seven children. While her brothers were sent to Germany for education, she never received a high school diploma. Her father, a military officer, thought of preparing his daughters for marriage. At the age of sixteen, she fell in love with the artist and writer Parvīz Shāpūr, her neighbour and distant relative, whom she married a year later. Their only son was born within two years, but their marriage did not last long. Farrukhʹzād could not accept the limitations and boundaries imposed on a married woman and thus asked for a divorce when their child was two years old. Consequently, the custody of the child was given to her husband, and she was not permitted to see him. She returned to her father’s house, where she faced his disapproval, another contributing factor to her mental breakdown. Later, she fell in love with the writer and filmmaker, Ibrāhīm Gulistān, a married man.

Rich was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1929. Throughout her life, she found herself in a border position. As a young girl searching for her identity, she attempted to connect with her Jewish heritage by marrying the Jewish professor Alfred Conrad in 1953. However, she did not find fulfillment in this state. She found it difficult to cope with the traditional expectations imposed by her mother-in-law, along with the challenges of pregnancy and raising three children. As a result, she left her marriage, began her struggles against patriarchy and racism, got involved in the women’s movement and soon embraced lesbian manifestos.6Albert Gelpi, “Adrienne Rich: The Poetics of Change,” in Adrienne Rich’s Poetry and Prose, edited by Barbara C. Gelpi, and Albert Gelpi (London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1993), 282–98. In 1976, she met Michelle Cliff, a Jamaican-born feminist and editor, who became Rich’s partner for the rest of her life.

Both Farrukhʹzād and Rich chose to leave their marriages to break free from the constraints of tradition and express themselves as social poets. They rejected traditions and the structure of family to reclaim their female identities. While revolutionizing their lives, they also began their careers by writing revolutionary and anti-conventional poetry. In their writings, they used corporeal imagery as a site of revolutionary power and insisted on combining gender issues with socio-political matters. By writing as women and not as objects of love and beauty, they could assert their identities and reclaim their voices, thus fighting for their individual and social freedom as social figures and pioneers of feminism. Their fearless expressions of their thoughts on sex and society required a revolutionary uprising from within their communities. They had to break away from the strict rules and regulations governing their language and writing styles to pave the way for a new identity. In fact, they could not be born into a new identity without dismantling their past ones.

Rich argues that women who conform to traditional gender roles are at odds with their potential as critical thinkers because they are limited by societal norms. She asserts that feminist activism is crucial in paving the way for feminist literary scholarship, which can help develop a new and dynamic approach to literature.7Adrienne C. Rich, “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision, 1971”, in On Lies, Secrets, and Silence, Selected Prose (London: W.W. Norton and Company, 1979), 34. In similar fashion, Farrukhʹzād decided to embark on long trips to Europe, visiting Italy, Germany, and England. She aimed to break free from traditional constraints, explore new perspectives, and gain knowledge. During an interview in 1343/1964 with the critic Sīrūs Tāhbāz and novelist and playwright Ghulām Husayn Sāʾīdī, she elaborated on her reasons for the journey:

For me, decay and exile are not death, but rather a stage from which one can begin life with a new outlook and a new vision. It is love itself, minus all the additions and extraneous things. It is a greeting, a greeting to everything and everyone without demanding or expecting an answer. The hands which can be a bridge for the message of fragrance, breeze and light grow green in this very exile.8Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 209.

After her travels, the focus of her poetry shifted. Her initial three collections, namely Asīr9Furūgh Farrukhʹzād, Asīr (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1334/1955). (The captive), Dīvār10Furūgh Farrukhʹzād, Dīvār (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1335/1956). (The wall), and ʿUsyān11Furūgh Farrukhʹzād, ʿUsyān (Tehran, Amīr Kabīr, 1336/1957). (Rebellion), dealt with personal themes of love, sex, and despair. Her later collections, however, Tavalludī Dīgar12Furūgh Farrukhʹzād, Tavalludī dīgar (Tehran: Murvārīd, 1342/1963). (Another birth) and Īmān biyāvarīm bih āghāz-i fasl-i sard13Furūgh Farrukhʹzād, Īmān biyāvarīm bih āghāz-i fasl-i sard (Tehran: Murvārīd, 1353/1974). (Let us believe in the beginning of the cold season), published posthumously in 1353/1974, tackled universal themes of equality and justice. Farrukhʹzād was not proud of her first three poetry collections, but she recognized them as products of the stage in which she revolutionized her life and poetry. In an interview with the poet M. Āzād, she said that she found herself immersed in the confined space of “family life.” Then, all of a sudden, she became devoid of all those familiar elements. She changed her surroundings, or rather, they naturally changed on their own. Dīvār and ʿUsyān were in fact “a kind of despairing struggle” between two stages of her life.14Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 197.

Likewise, in 1966, Rich left behind her past life and identity and moved to New York. This decision profoundly impacted her life and led to her growth as a poet. Her work began to focus less on personal themes and more on socio-political issues as she fought against injustice and inequality. This transformation is evident in her works, including Leaflets (1969) and The Will to Change (1971).

In her groundbreaking essay “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision” (1971) Rich argues that male artists have often portrayed women as luxuries, muses, caretakers, cooks, bearers of children, secretaries, and copyists. Women have been the subject of male writers’ description of beauty, vulnerability, and mortality. While for women artists, men have been a source of power, terror, and domination. According to Rich, women writers like Virginia Woolf have had to adopt a masculine style to compete with their male counterparts and maintain their integrity. Unfortunately, women have not been able to find role models in literature that reflect their experiences due to the dominance of male-centered language and literature. As a result, the image of the woman was given to female writers by male writers or female writers who imitated men.15Rich, “When We Dead Awaken,” 36–39.

Farrukhʹzād and Rich were successful in breaking the stereotype of women and instead wrote about men as the object of love. They believed that to rediscover their identities, they had to relinquish the traditional societal roles that women were expected to play. Rich argues that the first step towards survival is to revisit and reassess the past.16Rich, “When We Dead Awaken,” 35.

In their poems with the theme of rebirth, the similarities between “Īmān biyāvarīm bih āghāz-i fasl-i sard” and “Tavalludī dīgar” by Farrukhʹzād with “Winter” and “Necessities of Life” by Rich speak of the analogous paths these poets paved. By shedding their masks and conventional identities, they now journey through time to discover the origins of their being. Rich writes:

Dead, dead, dead, dead.

A beast of the Middle Ages

stupefied in its den.

The hairs on its body—a woman’s—

cold as hair on a bulb or tuber.

Nothing so bleakly leaden, you tell me,

as the hyacinth’s dull cone

before it bulks into blueness.

Ah, but I’d chosen to be

a woman, not a beast or a tuber!

No one knows where the storks went,

everyone knows they have disappeared.

Something—that woman—seems to have

migrated also; if she lives, she lives

sea-zones away, and the meaning grows colder.17Adrienne C. Rich, Collected Early Poems 1950-1970 (London: W.W. Norton and Company,1995), 277.

According to Marina Camboni, in this poem, “death” is splitting from the social body; it is self-exile and a critical distance between oneself and tradition.18Marina Camboni, Adrienne Rich: poesia e poetica di un futuro dimenticato (Effigi Edizioni, 2022), 29. Similarly, Farrukhʹzād writes:

And this is me

a lonely woman

on the threshold of a cold season

at the beginning of perceiving a contaminated existence

of the earth

and the simple and sad despair of the heavens

and the impotence of these concrete hands.

Time passed

Time passed and the clock struck four times

It struck four times

Today is the first day of winter

I know the secrets of the seasons

and understand the words of the moments.

The savior is asleep in the grave

and the dust, the receiving dust

is an indication of quiet.19Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 117.

Farrukhʹzād, like Rich, kills her historical and conventional “I” as if it were a corpse in a tomb. She must bury her old self to rise with a new, rebellious, and free identity. Her old self leads her towards the unknown, but the act of remembering can save her. As Camboni suggests, she must remember to reconstruct and transform her life from the very beginning, thus changing the time of dissolution to the time of creation:20Camboni, Adrienne Rich, 29.

Where do I come from?

Where do I come from,

that I have become so filled with the smell of night?

The dust of his grave is still fresh

I mean the dust of those two green and youthful hands.21Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 129.

In Farrukhʹzād’s poem, rebirth is the main key to salvation. Her poem “Īmān biyāvarīm bih āghāz-i fasl-i sard” depicts the metamorphosis that a woman is going through, which reaches its complete transformation with rebirth. This idea is similar to what Rich expresses in her poem “Necessities of Life” (1966), where she talks about the dissolution of the body in death as a necessary condition for rebirth:

Piece by piece I seem

to re-enter the world: I first began

a small, fixed dot, still see

that old myself, a dark blue thumbtack

pushed into the scene,

a hard little head protruding22Rich, Collected Early Poems, 205.

In fact, more than death, it is life in death that fulfils a central function, participating in the positive symbolism of incubation, heralding rebirth.23Camboni, Adrienne Rich, 29. Likewise, Farrukhʹzād writes in “Tavalludī dīgar”:

All my existence is a dark verse

which repeating you in itself will take you

to the dawn of eternal blossoming and growth

I have sighed to you in this verse, ah,

in this verse I have grafted you

to tree and water and fire.24Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 111.

According to Camboni, for Rich, the first act of non-being is renouncing the social meaning of things and criticizing the dominant language that distorts the image of women. This was also her first step towards survival, which allowed her to reconsider and analyze old texts with a fresh, critical perspective.25Camboni, Adrienne Rich, 30. Likewise, Farrukhʹzād buries her past identity to shape her new one:

Where do I come from?

I told my mother: “It’s all over now”

I said: “It always happens before you think

We must put our condolence notice in the paper.”

…

Let us believe

Let us believe in the beginning of a cold season

Let us believe in the ruins of imagination’s gardens

in the idle and overturned sickles

and the imprisoned seeds.

Look how the snow is falling …26Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 133.

Translation and Interconnections

Furūgh Farrukhʹzād

Farrukhʹzād is widely regarded as the pioneer of feminism in Iran for her lifestyle, poetry, interviews, letters and comments. She was well-versed in English, Italian, and German and translated poetry collections from these languages. Her translation of Margot Bickel’s German poetry is especially renowned. In 1956, Farrukhʹzād travelled to Italy and became familiar with Italian writers and poets. When in Rome, she studied Italian to “read the literature in the original tone of its creators.”27Nima Mina, “Forugh Farrokhzād as Translator of Modern German Poetry: Observations About the Anthology Marg-e man ruzi,” in Forugh Farrokhzad: Poet of Modern Iran; Iconic Woman and Feminine Pioneer of New Persian Poetry, ed. Dominic Parviz Brookshaw and Rahimieh Nasrin (London: I. B. Tauris, 2010), 150. As she wrote in a letter to her father, she improved her Italian and translated two books of Italian poetry from Italian.28Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 182. Later, she pursued her German and travelled to Germany , the country where her siblings had relocated to for their studies. She stayed in Munich, where her older brother Amīr Masʿūd lived. Together, they translated a collection of twentieth-century German exile poetry into Persian. The translation collection was published posthumously in 1980 as Marg-i man rūzī farā khvāhad risīd (My death will come one day).29Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, xi. The anthology contained poems that dealt with the themes of exile and the Holocaust and was originally published in 1955 by the exiled writer Eric Singer. The Persian edition also included a poem by Rainer Maria Rilke that was not present in Singer’s edition. The choice of translating this anthology was not a coincidence. Amīr Masʿūd had moved to Germany before the 1332/1953 Coup. During her stay in Munich, Farrukhʹzād made friends with Kūrush Lāshāʾī, his brother’s fellow student, who later founded the revolutionary wing of the Iranian Communist Party and was engaged in an armed uprising against the Shah’s regime. Mahdī Khānʹbābā Tihrānī, also a political activist and another friend of Amīr Masʿūd’s, had moved to Munich after his release from prison. Their conversations influenced Farrukhʹzād’s language and style, leading her to write social revolutionary verses. In her poetry collection, ʿUsyān, she writes:

This is the final lullaby

At the foot of your cradle of sleep

The wild hue of this cry perhaps

Through the sky of your youth will sweep

…

When o’er this confused and beginningless book

Your innocent eyes are drawn,

You will see the rooted rebellion of years

Has bloomed in the heart of every song30Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 15.

As Farrukhʹzād’s brother, Amīr Masʿūd, comments, among the poems included in Singer’s collection, she was particularly moved by the poems of Ossip Kalenter and it was under his influence that she wrote the poem “Baʿdʹhā.”31Mina, “Forugh Farrokhzād as Translator,” 152–54.

During her visits to Italy and Germany, Farrukhʹzād translated poems, plays, and stories from Italian, German, and French32Mahmūd Mushrif Āzad Tihrānī, Parīshāʹdukht-i shiʿr: Zindigī va shiʿr-i Furūgh Farrukhʹzād (The life and work of Furūgh Farrukhʹzād) (Tehran: Sālis, 1399/2012), 36. She was also well-versed in English literature and translated works by prominent English poets such as T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and Edith Sitwell. Additionally, she translated some works by Bernard Shaw and Henry Miller.33 Marzieh Khani, “Forugh Farrokhzad. Alla ricerca della libertà: Vita e opere della poetessa persiana,” in Altritaliani.net, https://altritaliani.net/Furūgh-Farrukhzād-alla-ricerca-della-liberta-vita-e-opere/. After becoming familiar with modern European poetry, the poet’s writing shifted from personal to political. She successfully wrote socially conscious poetry in her last two collections, Tavalludī dīgar and Īmān biyāvarīm bih āghāz-i fasl-i sard, blending the personal with the political.

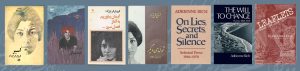

Figure 2: From left: The covers of Furūgh Farrukhʹzād’s poetry books: Asīr (The Captive), ʿUsyān (Rebellion), Īmān biyāvarīm bih āghāz-i fasl-i sard (Let us believe in the beginning of the cold season), and Tavalludī dīgar (Another birth). Also shown are the covers of Adrienne Rich’s books: On Lies, Secrets, and Silences: Selected Prose 1966–1978, The Will to Change, and Leaflets

Adrienne Rich

During the 1960s and 1970s, many North American poets used translation as their primary strategy in socio-political struggles. In modernist poetry, translation played a significant geopolitical role.34According to Gentzler, translation is one of the primary elements for the construction of cultures, therefore, to study cultural evolution and identity formation, translation should be considered. Edwin Gentzler, Translation and Identity in the Americas: New Directions in Translation Theory (London: Routledge, 2008), 2. They saw translation as an opportunity to open their way to other cultures and literatures. Rich had become a stranger to the American tradition of poetry. She believed that violence is the fruit of a masculine society and that women’s contribution could bring change. As a result, she was in search of a form and a language that could express her feminine identity without distinguishing between men and women. Rich was deeply interested in the poetry of revolution and resistance, particularly poets in the Middle East, such as Mahmoud Darvish, Nazem Hikmet Ran, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, and Furūgh Farrukhʹzād. She was also influenced by European and Latin American poets like Garcia Lorca, Pablo Neruda, Muriel Rukeyser, and Pier Paolo Pasolini. Rich believed these poets wrote against the “silence” of their time and location.35Adrienne C. Rich, “Poetry and the Forgotten Future,” A Human Eye: Essays on Art in Society, 1997–2008 (London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), 144. She emphasized the importance of translation in becoming familiar with the poets of revolution and resistance: “Without translations from other languages, I would have been severely deprived—unaware of the poetry of Yannis Ritsos, Nazim Hikmet, Mahmoud Darwish.”36Adrienne C. Rich, “Some Questions from the Profession,” Arts of the Possible (London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001), 133–34. She also read the original works of several French poets such as Hugo, Baudelaire, and Valery and the poems of many other European poets through translation, including Brecht, Rilke, Ungaretti and Ekelof. She was also familiar with Akhmatova, Tsvetayeva, Lorca, and Neruda.37Sandra Bermann, “Re-vision and/as Translation: The Poetry of Adrienne Rich”, Translating Women, edited by Luise von Flotow (University of Ottawa Press, 2011), 98. She underscored the importance of translation to her poetic career: “I’ve relied—both today and in my lifelong sense of what poetry can be—on translation: the carrying over, the trade routes of language and literature.”38Rich, “Poetry and the Forgotten Future,” 145.

Translation played a significant role in introducing new styles and poetic languages to Rich. In the early 1960s, she spent time in Holland, where she learned the Dutch language and translated some Dutch poetry by Hendrick de Vries, Gerrit Achterberg, and others. Later, while in New York, she participated in a translation project called “A Treasury of Yiddish Poetry.” As part of this project, she was asked to create poetic versions of poems by Kadya Molodowsky, Rachel Korn, and Celia Dropkin.39Rich, “Some Questions from the Profession,” 133–34. She declared: “I can’t emphasize enough how much my poetry has been stretched, enlarged, strengthened, fortified by the non-American poetries I have read, tangled with, tried to hear and speak in their original syllables, over the years.”40Rich, “Some Questions from the Profession,” 134. In her collection, Leaflets, many poems are adaptations of works Rich had read in translation or other languages. Some poems are inspired by the Dutch poet Gerrit Achterberg, the Jewish poet Kadia Molodovsky, the Russian poet Anna Achmatova, and the Russian prisoner poet Natal’ja Gorbanevskaja.41Camboni, Adrienne Rich, 154.

According to Alizadeh Kashani, a significant project that influenced Rich’s poetic language was the translation of Mīrzā Ghālib Dihlavī’s ghazals. She encountered the ghazal at a time of confusion in her private life and of socio-cultural turmoil in North America. Rich was searching for a solution for herself and her society, and the discovery of the ghazal became an essential part of her artistic expression. In 1968, Aijaz Ahmad, an Indian-born Pakistani Marxist-literary theorist, invited a group of North American poets to translate thirty-seven ghazals by the nineteenth-century Indian poet Mīrzā Ghālib for the centennial celebrations of his death. Ghazal is a classical poetic form, mainly practiced in Persian and Urdu. As a native speaker of Urdu, Ahmad provided the poets with English literal translations of the ghazals, along with lexical, historical, and cultural notes.42Neda Alizadeh Kashani, Adrienne Rich’s Ghazals and the Persian Poetic Tradition: A Study of Ambiguity and the Quest for a Common Language. PhD Thesis, Università degli Studi di Macerata: Ecum prints, archivio elettronico, 2014, 35.

Rich began writing in the ghazal form after translating Ghālib’s ghazals. She published her first collection of ghazals, titled “Ghazals: Homage to Ghalib,” in Leaflets.43This collection reflects “the social unrest of the anti-Vietnam War movement and the birth of the Women’s Liberation Movement as a renewed political and social force.” Cheri Colby Langdell, Adrienne Rich: The Moment of Change (Westport: Praeger, 2004), 88. The collection is a political volume that combines Rich’s experiences as a woman and a mother with the socio-political upheavals of her time.44Langdell, Adrienne Rich, 93. In The Will to Change (Poems 1968-1970), the poet published her second collection of ghazals, entitled The Blue Ghazals. The poems in this collection are replete with vivid imagery of life, memories of those dear to her heart, and images of dying individuals. Through her verses, the poet endeavours to express her yearning for transformation and change. Her poems in the collections Leaflets and The Will to Change were personal and political but were born under the influence of Ghālib’s poetry and the Islamic literary tradition.45Rich considered Ghālib a poet of resistance who wrote in “an age of political and cultural break up.” In the turmoil of 1968 in North America, she felt an affinity with Ghālib and likened his desperation to hers:

How is it Ghalib that your grief, resurrected in

Pieces,

Has found its way to this room, from your dark

House in Delhi?

Adrienne C. Rich, Leaflets (London: W.W. Norton & Company,1969), 68.

Cinematic Techniques and the Imagery of Classical Persian Poetry

Farrukhʹzād and Rich were poets who believed in the power of concrete imagery to transform language. They introduced new images into their poetry through translation and cinematic techniques. They were interested in cinematic techniques of shooting and used new methods of writing to give voice to women and to oppose patriarchy and oppression.

In 1956, Farrukhʹzād travelled to Italy to study cinematography and art. Upon returning to Iran, she joined Ibrāhīm Gulistān’s film studio and directed several documentary films. Her most renowned work, Khānah siyāh ast (The House is Black), won the best documentary award at the Oberhausen Film Festival in 1963.46Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, xi. Additionally, she acted in a play of Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, directed by Parī Sābirī in Iran.

Zīyā Muvahhid describes Farrukhʹzād’s poetry as visual. Comparing her poetry to film editing, he argues that her main contribution is in the order and relation between images.47Zīyā Muvahhid, “Furūgh Farrukhzād dar raftār bā tasvīr” (Forugh Farrukhzād in treating images), in Shiʿr va shinākht [Poetry and understanding] (Tehran: Murvārīd, 1377/1998), 130. Maryam Ghorbankarimi notes in “The House is Black: A Timeless Visual Essay”: “Her sensibility towards words in her poetry resembles her choice of editing style in The House is Black, a film that can be argued to have been conceived mainly in the editing room.”48Maryam Ghorbankarimi, “The House is Black: A Timeless Visual Essay,” in Forugh Farrokhzad: Poet of Modern Iran, ed. Dominic Parviz Brookshaw and Rahimieh Nasrin (London: I. B. Tauris, 2010), 141.

In her poetry, like in film editing, Farrukhʹzād uses a linear sequence of images and defamiliarization:

Let us believe

Let us believe in the beginning of a cold season

Let us believe in the ruins of imagination’s gardens

in the idle and overturned sickles

and the imprisoned seeds.

Look how the snow is falling …49Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 133.

In this stanza, the linear sequence of images leads the reader to the strange image of the garden, sickles, and seeds.

Likewise, in her book The Will to Change, Rich was heavily influenced by the techniques of new-wave cinema, specifically the cinematic styles of Jean Luc Godard and Pier Paolo Pasolini. The language of cinema encouraged her to enhance her poetic language by including more images and adopting more liberated forms, similar to the broken and fragmented shots in films. In this respect Rich writes:

I want the tradition of oral voice in poetry, the remembering of what they tell us to forget. I want the landscape of the visual field on the page, exploding formal verse expectations. I want a poetry that is filmic as a film can be poetic, a poetry that is theater, performance, voice as body and body as voice…50Adrienne C. Rich, “Poetry and the Public Sphere,” in Arts of the Possible (London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001), 118.

In fact, the most important aspect of poetry translation for Rich was the exchange of images as cultural elements in the contact zone. In this regard, Rich sustained that what remains in poetry translation are the images, which are the most important cultural elements.51Rich, “Foreword,” xx-xxi. For example, in a ghazal, Rich incorporates “dust,” one of the most important images of Ghālib’s poetry. She skillfully merges elements of Ghālib’s ghazal with a Western literary concept:

In the Theatre of the Dust no actor becomes famous

In the last scene they all are blown away like dust.52Rich, Leaflets, 62.

She creates the combination of ‘Theatre of the Dust’ which may be inspired by ‘theatre of the absurd’ or by Shakespeare’s “all the world’s a stage,” while she uses the word ‘dust’ with reference to Ghālib’s poetry, indicating the nullity of things.53Alizadeh Kashani, Adrienne Rich’s Ghazals, 200–1.

Rich’s poetry in the two volumes Leaflets and The Will to Change combined poetic images with visual images of photography and film together with references to Godard’s movies. A poem of hers entitled “Images for Godard” appears in the collection The Will to Change. An excerpt of this poems reads:

To know the extremes of light

I sit in this darkness

To see the present flashing

in a rearview mirror

blued in a plateglass pane

reddened in the reflection

of the red Triomphe

parked at the edge of the sea54Adrienne C. Rich, The Will to Change, Poems 1968-1970 (London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1971), 47–48.

These two collections, show a similarity between the use of images in cinema and the ghazal. Ghazal’s unity stems primarily from the association between images. Rich writes in this respect: “The continuity and unity flow from the associations and images playing back and forth among the couplets in any single ghazal.”55Rich, Leaflets, 59. She was inspired by the images of the Islamic tradition of Persian poetry found in Ghālib’s poetry. She adapted the imagery from Ghālib’s poetry into her own ghazals, creating images that were both erotic and political.56Alizadeh Kashani, Adrienne Rich’s Ghazals, 44. This allowed her to use poetic language that spoke for all humanity regardless of sex, race, or location:

Pain made her conservative.

Where the matches touched her flesh, she wears a scar.

The police arrive at dawn

like death and childbirth.

City of accidents, your true map

is the tangling of all our lifelines.

The moment when a feeling enters the body

is political. This touch is political.

Sometimes I dream we are floating on water

Hand-in-hand; and sinking without terror.57Rich, The Will to Change, 24.

In this ghazal, Rich associates the images of death and childbirth to the image of a city, and explicitly mentions the union of the erotic and the political. For this, she imitates the union of the amorous and the mystical in Ghālib’s ghazals and borrows some of Ghālib’s poetic imagery such as the “city” and “tangling”.

A Return to the Tradition: Revision of Classical Persian Poetry

Adrienne Rich

In her essay “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision,” Rich described re-vision as “the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction.”58Rich, “When We Dead Awaken,” 35. Along with other feminists, she sought new concepts, images, and forms not only in the works of women but also in the works of male writers from different times and places. The poetic form and tradition to which Rich turned for a transformation of her language and style was the one in which Farrukhʹzād was raised and her poetry formed. Like Ghālib, Rich and Farrukhʹzād deemed themselves poets of societies that were in crisis and needed restoration. It was precisely the forms and models of vision that connected these poets. Camboni writes that in Rich’s poetry, creative vision and imagination are united, and the words gain transformative power.59Camboni sustains that the concrete and mythical images that Rich found in the archaic civilizations or in the texts of other women writers turned for her into an historic patrimony and insight into culture and identity. Marina Camboni, “Come la tela del ragno: La costruzione dell’identità nella poesia di Adrienne Rich,” in Come la tela del ragno, Poesie e saggi di Adrienne Rich con tre saggi critici (Editrice universitaria di Roma, La goliardica, 1985), 164. It is similar to the tradition of Persian and Urdu poetry, where in the penetrating sight of the mystic, ahl-i nazar (people of vision) thought, vision, and word are united:60Camboni, “Come la tela del ragno,” 156.

The vanishing-point is the point where he appears.

Two parallel tracks converge, yet there has been no wreck.61Rich, Leaflets, 61.

In this ghazal, the image of the ‘vanishing point’ brings to mind the concept of the lover being annihilated to achieve union with the beloved. Additionally, Rich uses the word “appear” as the Sufi concept of “tajallī” (manifestation), which signifies the manifestation of the beloved or God.

Ghazal is a form of poetry that combines amorous and mystical elements and is widely used in the Islamic tradition. The ambiguity of the ghazal is partly due to the influence of Sufism, which added a mystical significance to Persian love poetry. This allowed the ghazal to be interpreted both as amorous and mystical, and for the two elements to be combined. The use of genderless pronouns in the Persian and Urdu languages and the fragmented description of the body in ghazal contributed to gender ambiguity in the ghazal or for the gender of the beloved to be concealed.62Alizadeh Kashani, Adrienne Rich’s Ghazals, 50-1. Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Muhammad Balkhī (d. 672/1273) known as Rūmī, whose major works Masnavī–yi ma‘navī and Divān made a great contribution to the mystical thought in Islamic heritage, in his ghazals combines the images of love and eroticism as well as those of nature with Sufi terms and traditions to form a mediating screen between earthly and divine love. After Rūmī, Shams al-Dīn Muhammad Hāfiz Shīrāzī (d. 792/1390) known as Hafiz, is recognized as the poet of the most ambiguous verses in the Persian literary tradition. The ambiguity in Hāfiz’s ghazals allows for a wide range of interpretations. In his ghazals, Hafiz fuses the physical and material with the metaphysical. Their ambiguity arises from the disunity of couplets, from the double meaning or ambience of the images, and from the obscurity surrounding the identity and gender of the beloved.63Alizadeh Kashani, Adrienne Rich’s Ghazals, 59-67.

In her poems, Rich replaces the ghazal’s amorous-mystical and gender ambiguity with an amorous-political ambiguity and an androgynous identity. She applies the ghazal’s ambiguity or duality to the relation between the carnal and the political to speak not only of women but also of all marginal groups, such as African Americans.64Alizadeh Kashani, Adrienne Rich’s Ghazals, 7.

In one of her ghazals, Rich explicitly speaks of the duality of the erotic and the political:

The moment when a feeling enters the body

is political. This touch is political.65Rich, The Will to Change, 24.

Another ghazal of Rich is dedicated to Amiri Baraka whom she calls the “Prince of the night.” In this ghazal, she draws a connection between the imagery of ‘night’ and ‘darkness’ to symbolize Baraka’s blackness and silence and contrasts it with the imagery of ‘light’ and ‘explosions,’ which represent his impactful words. Moreover, the word ‘wood’ in this poem is a reference to the word ‘orchard’ in Ghālib’s ghazals:66Alizadeh Kashani, Adrienne Rich’s Ghazals, 210.

Late at night I went walking through your difficult wood,

half-sleepy, half-alert in that thicket of bitter roots.

Who doesn’t speak to me, who speaks to me more and more,

but from a face turned off, turned away, a light shut out.

Most of the old lecturers are inaudible or dead.

Prince of the night there are explosions in the hall.

The blackboard scribbled over with dead languages

is falling and killing our children.

Terribly far away I saw your mouth in the wild light:

it seemed to me you were shouting instructions to us all.67Rich, The Will to Change, 22.

Forough Farrukhʹzād

As a young girl, Farrukhʹzād was an avid reader of literary books in her father’s library. This led to her writing of ghazals between the ages of fourteen and sixteen.68Mushrif Āzād Tihrānī, Parīshāʹdukht-i shiʿr, 36. Overall, her poetry was influenced by both the modernist works of Nīmā and Shāmlū, and the classical ghazals of Hāfiz and Rūmī.69Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, xii. Her maturation as a poet was achieved after she familiarized herself with non-Persian poetry and with the style of Nīmā, the founder of modern Persian poetry. In her last two collections, the traces of both Nīmā and the ghazals of Hāfiz can be noticed. Some of the poems in her last collection, such as “Āftāb mīʹshavad” (The sun rises), “Bād mā rā khvāhad burd” (The wind will take us away), and “Bih āftāb salāmī duʹbārah khvāham dād” (I will greet the sun once again), have also been compared to the mystical ghazals of Rumī in his Dīvān-i Shams.70Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, xx. An excerpt of the poem “Bih āftāb salāmī duʹbārah khvāham dād” reads as follows:

I come, I come, I come

With my hair exuding the smells beneath the earth

With my eyes, thick with experience of gloom

With the bouquet of greens I picked from the wood, on the other side of the wall

I come, I come, I come

The threshold fills with love

and I, on the threshold, will greet once again

those who love, and the girl

still standing on the threshold filled with love.71Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 109.

Farrukhʹzād believed in the union of the old and the new in her poetry, and succeeded in combining the features of the classical and new styles of the Persian poetic forms. She understood that the new context she was living in and her new identity needed new words and forms. To achieve this, she looked at the old texts from a new perspective and revised them, just like Rich did. By doing so, she successfully merged the old and the new in her poetry. Farrukhʹzād writes:

I looked at the world around me, at the things and the people around me, and at the basic outline of this world. I discovered all this, and when I wanted to express it, I saw that I needed words. New words, which are related to that same world. If I were afraid, I would die. But I was not afraid. I introduced the words. What was it to me if this (or that) word had not yet become poetic? Each has its own life; we would make them poetic. When the words were introduced, it introduced a need for changing and renovating the meters.72Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 197.

Farrukhʹzād’s first collections of poetry were in the Persian classical form of chahārʹpārah. However, after getting familiar with the Nimaic style, she began writing free verse. She was passionate about both Hāfiz’s ghazals and the blank verse: “Nīmā for me was a beginning. You know, Nīmā was a poet in whom I saw, for the first time, an intellectual atmosphere and a kind of human perfection, like Hāfiz… But the greatest impact Nima left on me was in terms of the language and forms of his poetry.73Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 195. In an interview, when questioned about the use of Western literature in her poetry, she stated that she relied solely on the forms of Persian poetry for the poetic structure and looked to foreign literature only for its content: “No. I looked at its content. That’s natural. But at the meter, no.”74Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 198. Nonetheless, she explained that although non-Persian poetry influenced her content, she always relied on Persian poetic forms, whether old or new, for the form and musicality:

Meter must exist. I am convinced of this. In Persian poetry, there are meters that have fewer metrical feet and are less rigorous, and that are closer to the rhythm of speech… One must mold the form into the words, not the words into the form… The difficulty lies in the fact that these two questions, that is, meter and language, are not separate from one another _ they go together, and the key lies in they themselves.75Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 199–200.

While Farrukhʹzād and Rich embraced new forms and imagery, they also incorporated some features of the traditional form, musicality, and imagery of Persian classical poetry. By their return to the tradition of Persian poetry, their linguistic poetics got closer.76As Javadi and Salleé write in their introduction, “A yearning for freedom, a sense of defiance of repression, and hope for a revolution have always existed in modern Persian poetry.” Javadi and Sallée, xxi. For instance, one of Farrukhʹzād’s poems, “Dar ghurūbī abadī” (In an eternal dusk), from the collection Tavalludī dīgar, shares similar concepts with one of Rich’s ghazals in Leaflets. In these poems, both poets desire change and want to speak out against oblivion; however, they do not find the right word to break the silence. Farrukhʹzād’s poem starts with:

_ Day or night?

_ No friend, it is eternal dusk,

with two doves like two white

coffins crossing in the wind,

and from that strange land

distant sounds, unfixed and vagrant

like a drifting breeze.

_ Something must be said.

It must be said.

My heart wants to mate with the dark.

Something must be said.

Such an onerous oblivion.

An apple falls from a branch;

yellow flax seeds break between

beaks of my lovesick canaries;

A fava bean flower, to release

her silent anxiety of change,

yields her blue veins to an intoxicated breeze.

And here, in me, in my head?

Ah…

There is nothing in my head except

swirling specks of turbid red,

…77Sholeh Wolpé, trans., Sin: Selected Poems of Forugh Farrokhzad (The University of Arkansas Press, 2007), 49.

And Rich writes:

The clouds are electric in this university.

The lovers astride the tractor burn fissures through the hay.

When I look at that wall I shall think of you

and what you did not paint there.

Only the truth makes the pain of lifting a hand worthwhile:

the prism staggering under the blows of the raga.

The vanishing-point is the point where he appears.

Two parallel tracks converge, yet there has been no wreck.

To mutilate privacy with a single foolish syllable

is to throw away the search for the one necessary word.

When you read these lines, think of me

and what I have not written here.78Rich, Leaflets, 61.

Conclusion

Farrukhʹzād and Rich were tired of the traditions that limited women’s creativity. They looked for modes of writing that could liberate them from the rules and regulations that hindered the expression of their new identity. They changed their context by abandoning the past and travelling and moving to new places, which transformed their mindset and opened their way to new forms, images, and themes. Translating and reading poetry from other languages enriched their linguistic poetics. In addition, they used revision as a strategy to look at older texts with a novel, fresh outlook.79As a feminist, Rich used the act of ‘re-vision’ as a strategy to look back to a text that belonged to another time and place and see it with fresh eyes to adapt its methods of writing and cultural features to her own time and requirements. Alizadeh Kashani, Adrienne Rich’s Ghazals, 14.

Through revision, Rich found her ideal language in the poetic form of the ghazal. It was a perfect medium for the expression of her new identity, a language that contrasted with the general assumption about conventional languages.80The feminists considered all conventional languages as patriarchal and therefore as a danger to women. Luise von Flotow, Translation and Gender: Translating in the ‘Era of Feminism’ (Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing, 1997), 9. The ambiguity of ghazal offered a space for women to express themselves. It allowed Rich to empower women by creating gender ambiguity and shattering the patriarchal norms of writing. Although the most famous ghazals had been mainly composed by male poets, it turned into a powerful tool in the hands of women poets.81“For feminist theory, the development of a language that fully or adequately represents women has seemed necessary to foster the political visibility of women. This has seemed obviously important considering the pervasive cultural condition in which women’s lives were either misrepresented or not represented at all.” Judith Butler, Gender Trouble, 1990 (London: Routledge, 2006), 2.

On the other hand, Farrukhʹzād was brought up in this poetic tradition and wrote in Persian classical poetic forms such as the ghazal. From a very young age, she was heavily influenced by the language and imagery of Hāfiz and Rūmī, two of the greatest ghazal poets. Although she left behind the old traditions and societal limitations to find a new life and identity, she never forgot her poetic heritage. Blank verse allowed her to express her new identity more effectively than the classical forms, and she also found themes in non-Persian poetry that changed her perspective. However, she never abandoned Persian classical poetry’s rhythm, musicality, or imagery. Rich and Farrukhʹzād blended the elements of modern style and imagery with the traditional meter, musicality, and symbolism of Persian classical poetry. Their poems are a unique fusion of the old and the new. Writing either in new or classical forms, translating and revising, Farrukhʹzād and Rich had one main goal: to become the voice of women and to write against oppression in their battle for freedom and equality for women and all human beings. Here are extracts of two poems by Farrukhʹzād and Rich expressing their desire to be the voice of women:

Farrukhʹzād writes:

The voice, the voice, only the voice

the voice of the translucent desire of water to flow

the voice of starlight pouring on the surface of the pistil of the earth

the voice of the conception of the seed of meaning

and the expansion of love’s common mind

The voice, the voice, the voice, it is only the voice that remains.82Javadi and Sallée, Forugh Farrokhzad, 165.

And Rich:

I am an instrument in the shape

of a woman trying to translate pulsations

into images for the relief of the body

and the reconstruction of the mind.83Rich, The Will to Change, 14.